The Devil Isn't The Scariest Thing About The Witch

Writer/director Robert Eggers came out swinging onto the horror scene with his debut film The Witch (famously stylized as The VVitch), which debuted at Sundance in 2015 before getting a wide release in 2016. Critics ate the movie up, earning it a 91 percent fresh rating on Rotten Tomatoes (including a Golden Tomato Award for Best Horror Movie 2016) and an 83 Metascore. It scooped up an impressive number of award wins and even more nominations at film festivals all over. Sure, general audience reaction was a little more mixed, but that's to be expected for a movie whose terror is more insidious, creepy, and slow than loud and crowd-pleasing. For horror fans, though, the film is rightly considered a modern classic.

The plot of The Witch focuses on the trials and tribulations of a family of Puritan separatists who find themselves removed from their community following an unspecified religious dispute. They make a new home on the edge of the wilderness, within which dwells their greatest fear: a witch, and with her, presumably the capital-D Devil. Eldest daughter Thomasin loses her infant sibling in a game of peekaboo gone about as catastrophically wrong as possible, and everything is downhill from there. But if the Devil is the Puritans' greatest fear, should he be ours? Is it the goat? Okay, but what about that bird? Or something else? (The rabbit?)

Wouldst thou like to live spoiler-free? Then proceed with caution because what follows is a discussion of the entirety of The Witch, delicious end and all.

G.O.A.T.

While the 20th century is replete with iconic movie monsters and killers, from Dracula and Wolfman to Michael Myers and Jason Voorhees to Pinhead and Ghostface, the 21st century has provided a relative dearth of instantly recognizable horror icons. There are a few, however, including the Babadook, the new version of Pennywise, uhhh, maybe the Cheddar Goblin? Otherwise it's mostly a lot (like, a lot a lot) of zombies and then evil abstract concepts or haunted VHS tapes or whatever. And then there's that huge, 210-pound, black-haired, bucking billy goat that looms over the family farm in The Witch: Black Phillip, who according to the family's young twins has a crown growing out of his head and who gets to utter the film's most quotable line, "Wouldst thou like to live deliciously?"

The Hollywood Reporter, in a piece that gives the whole scoop on Charlie, the all-too-real goat who portrays Black Phillip, claims "there's an argument to be made that Black Phillip's popularity has eclipsed that of the movie itself." In the absence of official merch featuring the hircine incarnation of the Devil, a huge market of unofficial merch exploded on sites like Etsy, as documented by The Witch's own distributor, A24. There's little question that Black Phillip is the film's star, its most ominous presence, and — apart from maybe Anya Taylor-Joy's large and expressive eyes — maybe its most indelible image. But when all is said and done, is this goat (and the suave pirate Devil he turns into) really what's supposed to give us nightmares?

Witch trials and witch tribulations

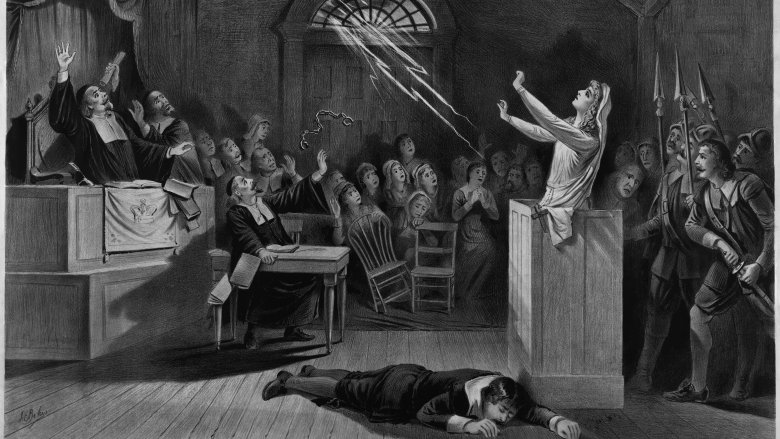

If you went to high school in the United States, chances are pretty good that you learned about the famous Salem Witch trials — or at least a somewhat fictionalized version of them — by reading Arthur Miller's 1953 play The Crucible, which used the paranoia and finger-pointing of the Salem hysteria as a metaphor for McCarthyism in an America that saw the red specter of Communism as just as frightening as the Puritans had seen the Devil. But allegory or no, the story of The Crucible and the 200 accusations of witchcraft and dozens of executions carried out in Salem Village in 1692 represented the climactic end to centuries of trials in Europe and America that saw tens of thousands of accused witches put to death.

The events of The Witch take place about 60 years before the events of the Salem Witch trials, but the Puritan New England setting means the environment is very much the same. The hardships experienced by deeply religious people (already inclined to see evil everywhere) that had moved across an ocean to make a home in a terrain and climate they knew nothing about meant that surely the Devil was responsible for their crops failing or their children and livestock dying. To these struggling Puritans, the Devil was real, and he was afoot, and his agents were everywhere. This fear and distrust would turn these villages into ... what's the word ... like, some kind of container in which the contents are exposed to very high temperatures.

Seasons of the witch

Besides Miller's The Crucible, there is a long legacy of witch- and Devil-themed literature and film that The Witch fits rather neatly into. The 1921 silent film Häxan, by Danish director Benjamin Christensen, is intended to be a documentary that ultimately proves witchcraft isn't real and that witch hysteria was caused by superstition and misunderstanding but is most notable for its scenes that, inspired by the 15th-century witch-hunting manual Malleus Maleficarum, recreate what would have been the popular conception of witches' covens with all their perversity and lascivious butter-churning motions. Since that time, there has been no shortage of witch movies and shows. Indeed, witches are having something of a moment, with Netflix's Chilling Adventures of Sabrina and Siempre Bruja and millennials' perpetual obsession with Hocus Pocus and Vulture arguing that witches are the icons we need right now.

Sometimes stories of devil worship and witchcraft are used to examine themes of human depravity and disillusionment as in Nathaniel Hawthorne's short story "Young Goodman Brown." Sometimes, as in Roald Dahl's The Witches and its film adaptation, Ira Levin's Rosemary's Baby and its film adaptation, and Suspiria, they deal with themes of paranoia and not knowing who to trust. And then you have movies like The Love Witch, The Craft, and The Witches of Eastwick that use witch stories to examine women's issues and female empowerment. Somewhat impressively, The Witch manages to touch upon every one of these themes in its 93-minute runtime.

The thing in the woods

The Witch, along with many other witch films, is also part of a horror subgenre known as folk horror, which deals with tension arising between the modern, civilized world (usually represented by Christian society) and something primordial and ancient (usually represented by pre-Christian pagan religions, frequently connected to witchcraft and devil worship). While the archetypal example of a folk horror film, 1973's The Wicker Man (not the Nicolas Cage remake), doesn't contain witchcraft per se, it definitely deals with the theme of Christian vs. pagan, with — spoilers for a decades-old movie — the pagan winning out in the end, but with no clear answers about which side had the moral high ground. 1968's Witchfinder General, which stars Vincent Price as a fictionalized version of real-life Puritan witch-hunter Matthew Hopkins, eschews supernatural elements but pretty clearly frames the severe and murderous Hopkins as in the wrong. Contrarily, 1971's The Blood on Satan's Claw also features a witchfinder, this time encountering real supernatural terror, and in this case coming out on top in a way that is meant to feel like a triumph of Enlightenment-era rationality.

The Witch falls squarely within this conflict between Christian civilization and pagan chaos, with the division between the two made literal by Thomasin's family's move to the edge of the forest. The tree line is a clear border: things on this side, the farm side, belong to God; anything more than a stone's throw is the Devil's domain. It's where the witch lives, after all. Right?

Fuel for the fire

Writer/director Robert Eggers put a lot of effort into historical accuracy in The Witch, ensuring clothes, tools, and language were as period-accurate as possible. Many lines — including the famous interview with the Devil at the end — were taken directly from transcripts of witch trials from the Puritan era. Even the stylization of the title as THE VVITCH is based on a specific document that spelled it that way (the letter w has a weird history). But even if these specific concrete details weren't spot on, the movie would still feel accurate because it exhibits the emotional atmosphere we expect from America's Puritan past, namely one of overwhelming repression.

When you hear the word "Puritan," repression of one's honest emotions, especially sexual ones, is likely the first thing that comes to mind. After all, the word "puritanical" now means excessively strict and rigidly austere. These are, after all, the people who outlawed Christmas because it was too fun, and fun is for Catholics and witches. Repression, consequently, runs rampant in Thomasin's family and indeed fuels pretty much all the conflict throughout the film. There's the way the father's pride causes him to keep secrets from his wife, the mother's anxiety about her two eldest children's budding sexualities, Thomasin's earnest concerns that her nostalgia for an easier life mark her as evil, and Caleb's desire to please his stern parents. All of this adds up to an explosive mix that ends with the entire family dead and only a newly born witch left standing.

What cometh before a fall?

When Thomasin and her family arrive at their new homestead on the edge of the woods, her father, William, declares, "We will conquer this wilderness." Spoilers, but, uh, they do not. The wilderness pretty handily takes home the W (or the VV as the case may be) on this one. But this blanket, ill-informed declaration is definitely representative of the stubborn pride at the heart of William's character.

It is, of course, William's pride that leads to the disagreement that sees them banished from the colony in the first place, an act that Eggers calls William's "original sin." Even after their crops start to die and his traps lie empty, William's pride keeps him from admitting that he needs the help of his community until it is too late. Additionally, his fear of admitting his failure leads to his not telling his wife that he had to sell her beloved silver cup to buy traps, allowing her to believe instead that Thomasin stole the cup, further damaging the relationship between mother and daughter. Rather than talk to his wife or his children about his fears and regrets, he bottles everything up and spends his time chopping wood until the firewood looms high by the house. This, of course, comes back to bite him. Pride, they say, cometh before something falls, right? William's stubborn refusal to admit to his own failings ultimately puts his family right in the Devil's sights and puts them all in an express lane to their own destruction.

You can't have a Puritan story without weird sex hangups

As Den of Geek says, it's important to understand that Thomasin is a good girl, or at least really, really wants to be one. She is the one member of the family who shows remorse at being forced to leave their community. Her first lines are a heartfelt prayer where she begs God for mercy and shows repentance for any doubts she has had about her father's (admittedly very terrible) choices for his family and her longing for the relative ease of her former life in England. But the fact is that to her parents, it matters little how good Thomasin is and much more how girl she is.

To her family, Thomasin is more a burden than an asset. More even than blaming her for the disappearance of the baby Samuel, Thomasin's parents distrust her burgeoning sexuality, even more so once it starts becoming a distraction for her repressed younger brother Caleb. Caleb, of course, is the only member of the family who doesn't turn against Thomasin, but his preteen hormones lure him into the clutches of the witch in a sexy disguise, who poisons him with an apple (this is also a sex thing; Adam and Eve, loss of innocence, etc.). William and Katherine fully intend to sell Thomasin to another family to be a servant in order to remove her sinful sexuality from the eyes of young Caleb. No one is going to live deliciously while they live under this roof, Thomasin; this is a Christian household.

I saw Goody Osburn with the devil

In the accounts of the Salem witch trials, including The Crucible — and, for that matter, in accounts of the surprisingly similar McCarthy hearings that Arthur Miller was examining in The Crucible — the air of paranoia leads to a strange circle of accusations. The only way to escape an accusation of being a witch or a Communist is to name names. If you're not a witch, surely you wouldn't mind telling us who is? This same circle of accusations happens on a smaller scale within Thomasin's family. When the twins Mercy and Jonas arouse suspicion by their constant association with Black Phillip, they simply turn the blame on Thomasin; she stops their prayers. She did, after all, in a moment of frustration "confess" to Mercy that she was a witch.

All this fear of the Devil has a powerful backfiring effect. Just as the overwrought piety of the people of Salem Village leads John Proctor to declare that God is dead in The Crucible, Thomasin's family's God-fearing ways leave little sign of God's providence for Thomasin. Despite begging for God's mercy, Thomasin finds herself at the receiving end of nearly all her family's accusations. Her twin siblings, too young to understand what they're doing, convince their parents Thomasin is a witch; her father's lie about the cup poisons the well of her relationship with her mother, already suspicious of her after the baby's disappearance, culminating in her mother attempting to kill her. The family accuses Thomasin of witchcraft so vehemently that she has little recourse but to throw in the towel and actually become a witch.

Better living through witchcraft

"It was not my intention to make a story of female empowerment," Eggers told the Atlantic, "but I discovered in the writing that if you're making a witch story, these are the issues that rise to the top." Ultimately, Thomasin's story is one of a young woman from an oppressive society finally, for better or worse, being able to exhibit agency. In her patriarchal Puritan community — especially in a household that apparently thought the larger community wasn't being Christian enough — Thomasin is completely stripped of agency. She exists solely to work around her family's farm until she is old enough to get married and have children. Notably, however, she would be doing this for her husband's family, not her own, which is another reason why a daughter would be seen as a burden.

No one ever asks Thomasin what she wants, until someone does: Would she like the taste of butter? A pretty dress? To see the world? To live deliciously? Her decision to sign the Devil's book is not a clear-cut, unequivocally happy choice; she is, after all, simply putting herself in the control of another man, a man who is, you know, the Devil. But it is her choice, which sees her surrounded by likewise liberated women around a fire who are clearly having a pretty good time, even if that good time does technically involve turning babies into a pinkish, flight-inducing skin cream. Thomasin decides to live as a free witch rather than die an oppressed Puritan.

Fear is a self-fulfilling prophecy

The AV Club argues that The Witch comes dangerously close to sympathizing with the real devils — namely, the historical Puritans who executed real innocent people on false charges of witchcraft — by showing that within the framework of the movie, witches and the Devil are real. First of all, of course witches are real within the movie. It is, as the subtitle says, "A New England Folk-Tale." As Eggers told the Atlantic, "All of this is 'literal truth' in the period." Witchcraft was entirely real to the people within the story, so why shouldn't the movie present their story as such? But more importantly, by no means do the witch-fearing Puritans come out clean on the other side of this. Indeed, they are more responsible for their own downfall than the Devil is. Nowhere is this made more evident or literal than the fact that William dies crushed under the physical manifestation of his own pride, the pile of firewood that he added to rather than confronting his true fears and anxieties? If you touch a hot stove and burn yourself, do you blame yourself or the stove? Like the scorpion who stung the frog, it is the Devil's nature to tempt; it's our job to resist him (or not).

Does the witch live in the woods? The witch lives in all of us, as it lived in Thomasin, and it will come out if we are forced into a position where we have no other choice. We all deserve the taste of butter; we shouldn't have to turn to the Devil for it.