Disturbing Facts About Serial Killer Ted Bundy

In the early morning hours of August 16, 1975, Utah highway patrolman Bob Hayward saw a tan Volkswagen Beetle parked outside a home where it didn't belong. Residing at the home were teenage girls whose parents were away. It was an ominous scene at a time when women were being murdered with terrifying frequency. The driver bolted after noticing Hayward but stopped at an abandoned gas station. Hayward had unknowingly caught Ted Bundy.

Bundy was a nightmare with a nice smile who used his charming veneer to lure, rape, and kill his victims. By the time he crossed paths with Hayward, he had murdered at least 25 women across four states. "I didn't want to shoot the guy," Hayward later recalled. "I wish I had." Instead, he arrested Bundy after uncovering incriminating items in the Volkswagen.

Twice in 1977, Bundy eluded justice, once by leaping from a courthouse window and later by sawing a hole in the ceiling of his jail cell. He continued killing until he was apprehended for good in 1978. Prior to his execution in 1989, he admitted to raping and murdering 36 people, including a 12-year-old girl. Yet he somehow enjoyed a grotesque celebrity that persists to this day. Here we attempt to explore Ted Bundy's origins, his possible motivations, and the jarring stardom he garnered.

When Ted Bundy became Hannibal Lecter

In 2019, Washington Post columnist David von Drehle proclaimed that Ted Bundy "was no Hannibal Lecter," but rather "a savagely violent sex criminal" who tricked the public into perceiving him as a "suave up-and-comer." But Lecter was a cannibal who, much like Bundy, hid his savagery behind a likable facade. In fact, the character is partly based on Bundy.

The books "Red Dragon" and "The Silence of the Lambs," wherein Lecter helps detectives nab serial killers, were directly inspired by the interactions between Ted Bundy and Detective Robert Keppel. Bundy reached out to Keppel from prison in 1984 to offer assistance in catching the Green River Killer, a then-faceless predator (later identified as Gary Ridgway) who killed almost 50 sex workers in Seattle. Bundy's theories about the killer were disturbingly accurate. He knew Ridgway would keep returning to where he buried his victims and recommended a clever way to catch him.

According to his 1995 book "The Riverman: Ted Bundy and I Hunt for the Green River Killer," Keppel suspected that Bundy's guesses about the Green River Killer were largely "a projection of himself." However, Bundy also saw himself in Keppel because they were both "hunters of humans" (per the New York Post). His respect for the detective prompted him to open up about his own crimes.

What Bundy's necrophilia may say about his motives

Ted Bundy was unsettling on many levels, and the way he behaved toward corpses made his crimes all the more disturbing. A rapist and self-confessed necrophile, he violated his victims before and sometimes days after killing them. When asked by psychologist Al Carlisle about his necrophilia, Bundy explained that he wanted to possess "the essence of the victim" (per A&E True Crime Blog). Why his urge to "possess" people took such a ghastly form is anyone's guess, but neuroscientist Jack Pemment had a pretty intriguing idea.

Based on recordings featured in "Conversations With a Killer: The Ted Bundy Tapes," Pemment concluded that Bundy's acts were rooted in a "desire for ... intimacy" (via Psychology Today). Specifically, he suggested the killer was trying to recreate the closeness he lost after a traumatic breakup with girlfriend Diane Edwards. Bundy placed their relationship on a pedestal, idealizing Edwards' looks and the time they spent together. He later felt that a corpse could "be anyone he [wanted] them to be."

Bundy enjoyed watching his victims decompose. In some instances, he apparently shampooed their hair and painted their fingernails. Sometimes he kept their severed heads until he no longer wanted to be near them. Perhaps in some twisted, sadistic way, he viewed his victims as romantic partners who couldn't leave him.

A childhood steeped in confusion and cruelty

Before his long-delayed trip to the electric chair, Ted Bundy insisted his depravity had nothing to do with how he was raised. Per the Los Angeles Times, he claimed he was brought up in "a wonderful home with two dedicated and loving parents" and painted a portrait of familial bliss devoid of the slightest vice. His relatives, however, told a drastically different story.

In this alternate picture, Bundy's upbringing was filled with deception, chaos, and cruelty. For years he was told his mother was his sister and that his grandparents were his parents, to conceal that he was born out of wedlock. The man he called "Dad" was vicious and unstable. As psychiatrist Dorothy Lewis described (per the Associated Press), Bundy's grandfather, Samuel Cowell, "would kick dogs, swing cats by their tails, [and] beat people who angered him." He also argued with hallucinations.

At age 3, Bundy would lay butcher knives beside his sleeping aunt. In the 2019 Netflix special "Conversations with A Killer: The Ted Bundy Tapes" (via USA Today), a childhood friend recalled that Bundy set "tiger traps," which were "[pits] with pointed stakes, disguised with vegetation." Bundy's psychiatrist posited that he was mentally ill (possibly bipolar) since infancy, which along with his horrific home life might help explain how he turned out.

From lonely peeping Tom to deadly predator

Growing up, Ted Bundy struggled with loneliness. According to psychologist Al Carlisle, as a kid Bundy felt overshadowed by his step-siblings after his mother married Johnnie Bundy (per A&E True Crime Blog). Though he later claimed on tape he had plenty of friends to keep him company, one of his actual childhood friends said Bundy "had a horrible speech impediment, so he was teased a lot," according to "Conversations with A Killer: The Ted Bundy Tapes" (via USA Today).

Often feeling insignificant, Bundy retreated into his own mind where he imagined being "someone important." He listened to the radio and imitated the accents of politicians he heard. In high school, he was known to try to trick people. Perhaps tellingly, as a serial killer he would sometimes attempt to trick women by mimicking a British or Canadian accent and pretending to be injured.

As a teen, Bundy began peeping through women's windows. He didn't date in high school, and when he finally fell for someone, she dumped him for being dishonest and nonassertive. Emotionally shattered, he coped by breaking the law. After a failed foray into politics and a failed stint at Temple University, he felt even lonelier and spiraled into violence. Obviously, loneliness didn't cause Bundy to kill, but it seems related, especially when you consider that he claimed that killing women made them a part of him forever, per Katherine Ramsland's "The Mind of a Murderer."

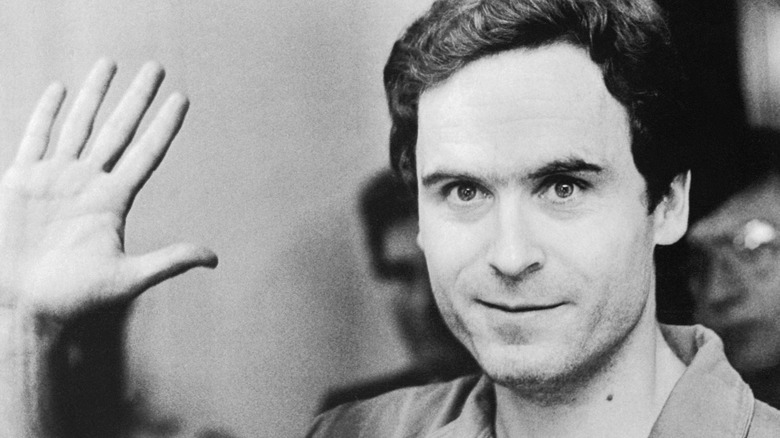

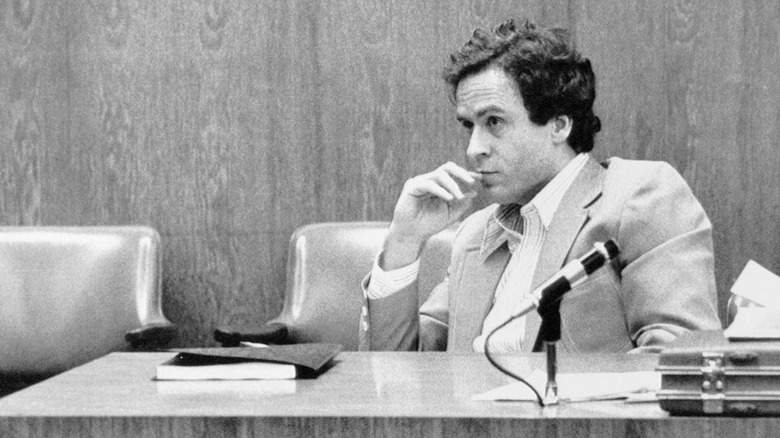

What you see is what gets you

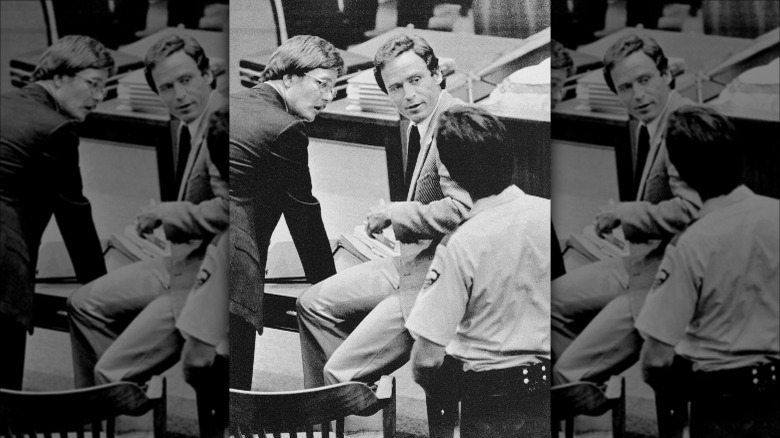

In 1978, The New York Times described Ted Bundy as an "all-American boy on trial." A murder-weary nation watched incredulously as a smartly dressed "terrific-looking man" stood accused of barbarically killing young women for years. It was utterly flummoxing for a public used to thinking that murderers vere visibly different from the rest of society.

Bundy didn't just look good; he sometimes acted like a good guy. In the past, he reportedly ran down and subdued a purse snatcher and saved drowning children. He even served as the assistant director of Seattle's Crime Prevention Advisory Commission and wrote a rape-prevention pamphlet. While living and killing in Utah, Bundy became an active member of the Mormon church and enrolled in law school.

At first, much of the public viewed Bundy as the victim of overzealous prosecutors, crooked cops, and a vengeful fiancee. He used that perception to his advantage and turned court proceedings into sideshows built around his supposed squeaky-cleanness. Acting as his own attorney, he questioned girlfriend Carole Boone on the stand. After getting her to say he wasn't creepy, he popped the question, and they tied the knot in the middle of the hearing. (Boone later had a daughter by Bundy but divorced him after he confessed to his crimes.)

A destabilizing kind of love

Ted Bundy's string of rapes and murders partly overlapped with a serious relationship in which he nearly married and tried to murder his girlfriend. That unlucky soul was Elizabeth Kloepfer (also known as Liz Kendall), who dated Bundy for six years, according to her book "The Phantom Prince: My Life With Ted Bundy." When they became acquainted in 1969, Kloepfer was a lonely single mother consumed by alcoholism. She had moved from Utah to Washington after divorcing a man she discovered was a convicted felon. Ironically, she introduced herself to Bundy at a bar in order to dodge a different "creep."

Perhaps as the lonely son of a troubled unwed mother, Bundy felt at home with Kloepfer. He later claimed in a taped interview that he loved her in a "destabilizing" way (via Oxygen). Each year, he celebrated the day they met by giving her a rose. He behaved like a father to her daughter. However, his warmth was interspersed with unpredictable coldness and fury. He even ripped up what would have been their marriage license because she worried about her old-fashioned parents seeing his belongings in her apartment. When evidence of Bundy's crimes mounted, an emotionally dependent Kloepfer remained in denial. However, she ultimately warned law enforcement. While behind bars, Bundy told Kloepfer he fought the urge to murder her but once blocked a chimney in hopes of killing her through smoke inhalation.

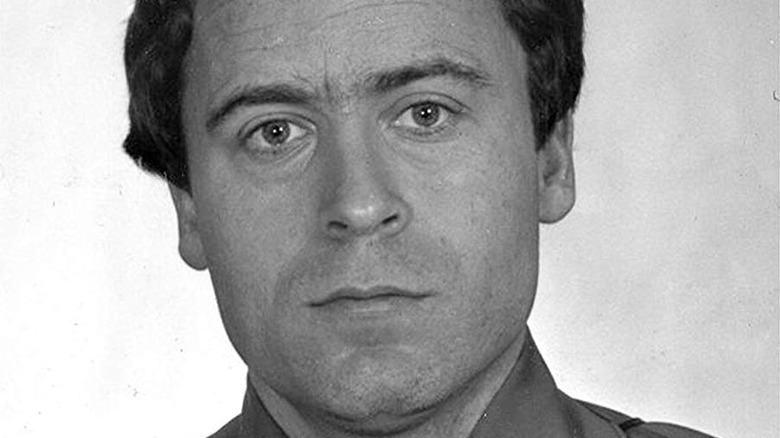

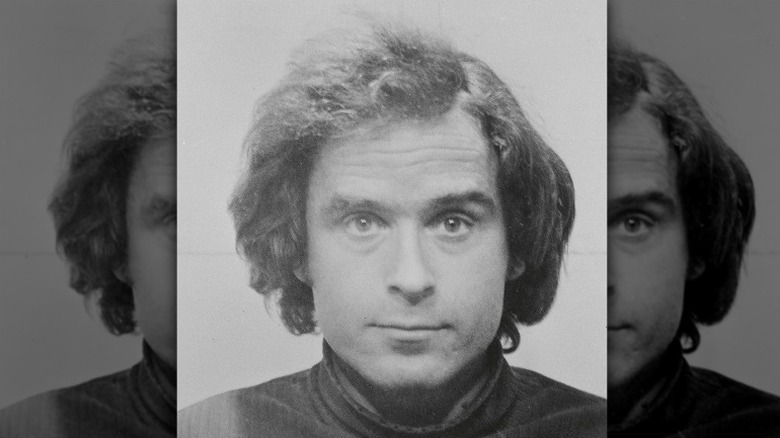

The Ted Bundy effect

Ted Bundy is an exceedingly grim example of how deceiving appearances can be. But even if you wanted to judge him by his cover, that cover changed so often that it's unclear who the "authentic" Bundy was, or if there was one at all. He constantly altered his hairstyle and "made himself look completely different," said journalist Stephen Michaud in Netflix's "Conversations With a Killer: The Ted Bundy Tapes" (per Oxygen). He could be cleancut, hairy, rugged, or downright frightening.

His many transformations weren't just follicle-deep. "Bundy became whatever he thought he needed to be," according to forensic psychologist Dr. Katherine Ramsland (via Psychology Today). He could go from showing deep devotion to callous indifference. When he wanted to hide a crime, he seemed to sincerely believe his lie. Those who knew him on different levels have likened Bundy to a Kennedy, a cave-dwelling animal, and an ideal boyfriend.

Maybe Bundy felt most comfortable being someone else. After all, his grandparents pretended to be his parents, his mother pretended to be his sister, and in childhood he fantasized about becoming other people, too. It's also possible that his transformations weren't always voluntary. Psychiatrist Dorothy Lewis, who assessed the killer before his death, suggested that Bundy suffered from dissociative identity disorder, formerly known as split personalities, or bipolar disorder.

Cracks in the mask

No matter how good you are at hiding your true self, your performative mask will eventually crack. Marylynne Chino saw it happen with former friend Ted Bundy. She first saw the infamous killer at Seattle's Sandpiper Lounge in 1969. At the time he didn't seem evil, Chino told KUTV. Instead, "Ted was charismatic, he was nice."

Chino's best friend, Elizabeth Kloepfer, got into a serious long-term relationship with Bundy, which she detailed in her book "The Phantom Prince: My Life With Ted Bundy." Inevitably, indications of his dangerousness began to stand out. As Chino recalled, Kloepfer called her after discovering women's undergarments and the plaster of Paris, which Bundy ostensibly used to make casts to fake injuries and abduct women. He reportedly warned Kloepfer, "If you ever tell anyone this I'll break your effing head."

When women started vanishing and police released a sketch of the suspect, Chino and Kloepfer thought it was Bundy. Though they eventually alerted law enforcement, initially they backtracked when an officer they contacted misidentified the color of Bundy's car. That didn't mean they trusted Bundy, though. When he insisted on driving Chino home one night, she was petrified, calling the 30-minute ride the longest of her life. Decades later, she still questioned why he didn't kill her.

Bundy's pet mice

Days before he died, Ted Bundy divulged things to Detective Robert Keppel that no ear should ever hear. But occasionally his confessions went in a surprising direction. According to transcripts of their recorded sessions, in 1974, Bundy did an about-face after luring a woman to his Volkswagen. "I reached all the way to the car," he claimed, "and this happened, would happen sometimes, [I just thought] no, I don't want to do it. I said, `Thank you. See you later.' And she walked away." Was that remorse talking? Highly doubtful — even his acts of "mercy" had sinister underpinnings.

When Bundy was a boy, he enjoyed buying mice from a pet shop. As his former defense attorney, John Browne, explained in his book "The Devil's Defender" (via Fox 13 Seattle), "He'd go to the woods and build a little corral, and then he'd decide which ones to kill and which ones to let go." It was Bundy's way of playing God. That's also how he viewed his human victims. For him, choosing not to kill was just another way to control life and death, which may also explain why Bundy once worked for a suicide crisis hotline.

True crime and false innocence

In 1971, Ann Rule was a 40-something-year-old mother of four whose marriage was on the rocks. Previously a police officer, she was trying to get by as a crime reporter. Once a week she volunteered at a suicide crisis hotline, where she bonded with fellow hotline worker Ted Bundy.

Bundy opened up to Rule about his grandmother pretending to be his mother and even discussed his love life. He likely wasn't a full-blown murderer back then but had probably attempted to abduct women. You might think someone with Rule's police training would've spotted the monster behind Bundy's smile from a mile away. But as she would later write in "The Stranger Beside Me," "As far as his appeal for women, I can remember thinking that, if I were younger and single — or if my daughters were older — this would be almost the perfect man."

Rule would later be assigned to write about a series of murders that turned out to be Bundy's doing. When he was arrested, she held out hope for his innocence, but that hope faded when he broke out of jail and went on a killing spree. Even then, she remained his friend and became his biographer.

Bundy and the war on smut

When someone behaves as horrifically as Ted Bundy, it's natural to want to know why. Pinpointing a clear-cut cause would suggest there's a clear-cut remedy. In 1989, Bundy placed the bulk of the onus on pornography and alcohol. Speaking with evangelist and psychologist James Dobson, he said the sleazy imagery he saw at grocery stores served as a gateway to more violent material and ultimately violent behavior. Bundy warned that adult entertainment "can reach out and snatch a kid out of any house today" (via the LA Times).

With that, Ted Bundy became the dire face of the anti-porn movement, and fundraising efforts abounded. However, there are reasons to be skeptical of Bundy's account. For starters, studies from multiple countries suggest that increased porn consumption corresponds with an overall drop in sex crimes. More importantly, according to criminologist Dr. William Wilbanks, it's "naive" to believe that Bundy knew the "'real reasons' for his behavior and that he would reveal those reasons to us if he knew them" (via the Sun Sentinel). It's worth noting that Bundy insisted he grew up in a wholesome, loving household, despite strong evidence to the contrary. What if he was simply trying to preserve the illusion of normality?

Zac Efron and the halo effect

For many people, Zac Efron is the kind of eye candy that can make you weak in the knees with a single, smoldering glance. So the thought of Efron playing a manipulative rapist and murderer might be a tad disconcerting. But that's exactly what Efron did in the 2019 film "Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil and Vile," wherein he portrays Ted Bundy. As described by The Washington Post, detractors of the film argued that it rightly highlights Bundy's "disturbing celebrity" but "doesn't do enough to confront it." Viewers reportedly felt "awkward" lusting after "Hot Ted Bundy." Some critics accused the movie of "romanticizing" the serial killer.

It makes sense to be concerned about glorifying a monster. But maybe the real problem is the underlying assumption that being good-looking makes you a good person. This isn't simply something we do with movies. It's part of a real-life phenomenon known as the halo effect, whereby people use a single trait to judge the totality of a person. The real-life Bundy benefited greatly from this bias. His defense attorney, Margaret Good, said female admirers wrote notes to Bundy during his murder trial. As one woman put it, "He just doesn't look like the type to kill somebody" (via ABC News).

His biological father wasn't around

Ted Bundy's biological father hadn't been present from the start. Bundy was born at the Elizabeth Lund Home for Unwed Mothers, and he may not have had much of a description of his father since a tight-lipped Eleanor Cowell only described the man as a sailor, per Ann Rule's "The Stranger Beside Me." He did have a father figure in Sam Cowell, his grandfather, who Bundy once believed was his actual father. But Sam was imperfect in that role, according to psychologist Dorothy Otnow Lewis, who analyzed Bundy before his execution. Sam was reportedly a brusque and violent individual and not the warm, grandfatherly type.

According to "The Stranger Beside Me," Bundy decided to do his own digging once he was an adult. He looked up records at the Burlington, Vermont, city hall and found that his father was listed as "Lloyd Marshall." Marshall supposedly attended Pennsylvania State University, had served in the Air Force, and had been employed as a salesman. Eleanor said she met Bundy's father through a friend while she was working as a clerk at an insurance company.

Ted Bundy may have been popular in high school

In Stephen Michaud and Hugh Aynesworth's "Conversations With a Killer," Ted Bundy paints a picture of his high school years as lonely, isolated, and tainted by his inability to make friends. He felt as if his social development between junior high and high school had been inexplicably stunted, and he watched helplessly as his old friends grew and changed. He was painfully aware of his small frame, which impeded his ability to forge a path in sports. He was also bitter about the socioeconomic gaps between him and his peers, who lived in better houses. Most of all, he was confused that he couldn't grasp the new social mores that high school presented. It was as if his social development peaked in junior high.

However, Bundy's account doesn't completely jive with the memories of his classmates. According to Ann Rule's "The Stranger Beside Me," a former female classmate recalled that although Bundy was somewhat reserved, he had no trouble making friends or finding dates. People liked him and found him pleasing to the eye, and he would attend school dances. Even if he didn't participate in the student council or other in-crowd groups, his friends certainly did.

He studied psychology and law in college

Once out of high school, Ted Bundy did some college-hopping and enrolled at the University of Puget Sound before settling at the University of Washington (pictured). He elected to study Chinese, but that wouldn't last, either. After falling in love with another student and getting his heart broken, Bundy seemed to have a shift in focus and changed his major to urban planning before ultimately settling on psychology, ironically enough. His record as a student was subpar, as he was forced to temporarily drop out because of bad grades. Maybe it had something to do with his unsavory extracurriculars: Some believe that his first murders occurred at this time. But his grades improved enough when he re-enrolled that he graduated with distinction and even disappointed a psychology professor when he set his sights on attending law school in 1973.

But Bundy would never end up graduating from the University of Puget Sound Law School. He began murdering more women, killing at least seven in the summer of 1974, and was nearly arrested. He later studied law at the University of Utah, but by then the murders and disappearances were getting public attention, and it wouldn't take long before he was arrested for the first time in 1975.

He got married in prison

In 1974, Ted Bundy began working at the Washington State Department of Emergency Services, which had organized hunts for some of Bundy's missing victims, according to Stephen Michaud and Hugh Aynesworth's "The Only Living Witness: The True Story of Serial Sex Killer Ted Bundy." Bundy was popular in the office; his male coworkers admired him and were even envious. He raised interest among his female coworkers, to say the least, one of whom was Carole Boone, his future wife and mother of his lone child. At the time they were only close friends, as Boone's love life was a mess and Bundy was attached to Liz Kendall. But they would soon reunite, their bond stronger than ever.

When Bundy was on trial, Boone was perhaps his biggest ally. She believed he was innocent and testified to his good character during the trial in 1979. She even did embarrassing favors for him, like smuggling drugs that she placed in her vagina into prison. They married in the courtroom while Bundy was on trial. The romance ended when Bundy eventually admitted to his crimes, which shocked Boone.

He was devious as a political aide

Ted Bundy's political career began when he was only in high school as a volunteer during a local election, according to Stephen Michaud and Hugh Aynesworth's "The Only Living Witness: The True Story of Serial Sex Killer Ted Bundy." The experience must have left an impression on him because he returned to politics in the form of lieutenant governor candidate Art Fletcher's driver and bodyguard.

After he graduated from the University of Washington, Bundy worked as an aide for Washington Governor Daniel J. Evans' re-election campaign. It was here that Bundy engaged in some political machinations that would've made Richard Nixon proud. According to a report at the time by The New York Times, Bundy pretended he was a college student in order to infiltrate the campaign of Evans' opponent, Democrat Albert D. Rosellini. Bundy walked about the campaign with a tape recorder to capture Rosellini's answers to questions on issues. But the subterfuge wasn't too scandalous since Rosellini's remarks were already made public. In true Bundy fashion, he said he had no regrets about the ethics of his lie.

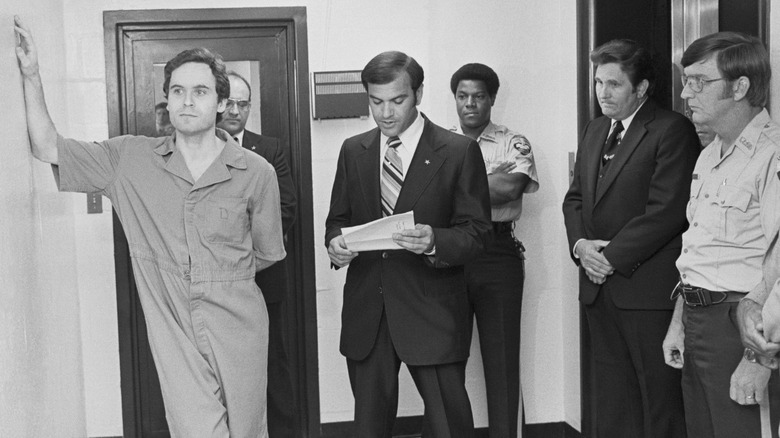

He pretended to be a cop to lure victims

Ted Bundy found various ways to get unwitting women to trust him and lead them into isolation. One strategy was impersonating a police officer, which itself is a crime, but this tactic would soon lead to his first arrest. It was November 8, 1974, when Bundy approached Carol DaRonch at a shopping mall in Murray, Utah. Posing as a cop, he told DaRonch that someone had tried to break into her car and requested that she ride with him to the Murray Police Department. She agreed, but as soon as he pulled over too soon and handcuffed her, she knew something was wrong. Quick on her feet, she managed to escape Bundy's car and hitched a ride to the police department to report Bundy. A description of Bundy and his car was now on file, and he would be identified a year later by a highway patrol trooper, leading to his overdue arrest.

Bundy used other disguises to trick women. He would use crutches to appear vulnerable and then ask others for help. These were likely the same crutches that Bundy's girlfriend Liz Kendall once spied in his apartment, as detailed by Stephen Michaud and Hugh Aynesworth's "The Only Living Witness: The True Story of Serial Sex Killer Ted Bundy."

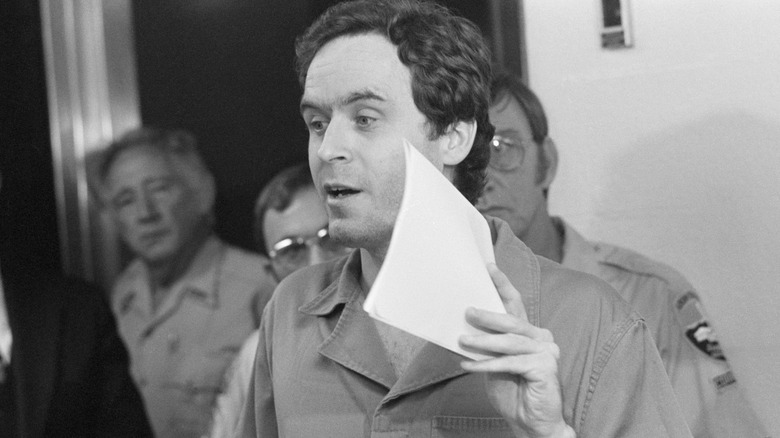

He escaped prison twice

Once in custody for the aggravated kidnapping of Carol DaRonch, police discovered Ted Bundy's connections to another crime: the murder of a nurse in Snowmass, Colorado. While being held at the Pitkin County Courthouse in Aspen (pictured), Bundy was allowed access to the courthouse library since he was representing himself. No one seemed to fear that he would escape, since they didn't bother to cuff his legs or arms. It was June 7, 1977, when Bundy made his first jailhouse escape, jumping from a second-floor window while the guard was taking a break. Aspen went on high alert and schools closed down when news spread of Bundy's escape. Some even had fun with it, as local businesses began selling Bundy-themed shirts and burgers. Bundy was in custody again a week later.

His second escape required more imagination. While in custody at Garfield County Jail in Glenwood Springs, Bundy lost about 20 pounds. He starved himself deliberately so he could fit through an opening in the ceiling that was supposed to hold a light fixture. He managed to escape through the ducting. This time, Bundy's freedom did not inspire jokes; he flew to Chicago and drove to Tallahassee, Florida, where he would murder his last three victims.

The Chi Omega murders were his last killing spree

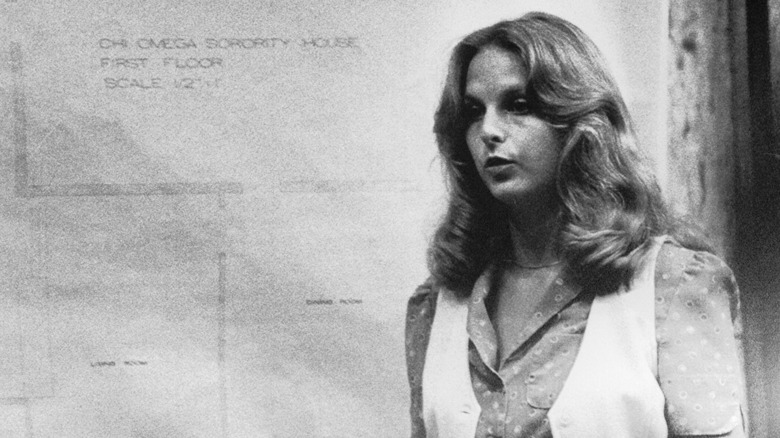

Fears that Ted Bundy would strike again and target more women after escaping prison a second time were justified. In the early hours of January 15, 1978, Bundy broke into the Chi Omega sorority house at Florida State University with a wooden club. Wearing pantyhose over his face, Bundy snuck into the home and murdered two students, Lisa Levy and Margaret Bowman. Two other students, Karen Chandler and Kathy Kleiner, were severely beaten. Sorority member Nita Neary (pictured), however, managed to catch a good look at Bundy's face, and the resulting sketch helped investigators connect him to the incident.

But that wasn't the end of Bundy's crime spree that night. Once he left the sorority house, he sought his next victims a few blocks away. Bundy climbed in through student Cheryl Thomas' kitchen window and physically assaulted her. Fortunately, her neighbor heard the commotion and saved her life. Bundy managed to escape, and three weeks later, he kidnapped and murdered 12-year-old Kimberly Leach in Lake City, Florida, in what his believed to be his last attack. Bundy was sentenced to death twice: once for the murders of Bowman and Levy and the second time for the murder of Leach.

His IQ was above average

Ted Bundy is said to have had an IQ of 136, which would make him above average, but only just. Around the internet, descriptions of Bundy follow a familiar pattern: He was a good student, but not an exceptional one; he was a B-plus student in high school; and he struggled with bad grades during his first stint in college but still impressed professors. So what if Bundy wasn't exactly a genius, as the traditional, sexy narrative about serial killers tends to go? Bundy led his own defense at his murder trial, and he hadn't even graduated law school. His performance as a lawyer impressed even the judge, who said that it was a shame Bundy was wasting his intelligence.

But this isn't the complete picture of Bundy's smarts. Although he might've been charismatic as a lawyer, he would often put his own case at risk and cause onlookers to question his sanity. During cross-examination, he asked first responders to describe his crime scenes in detail, evidently because he enjoyed it, even though it did him no favors with the jury. He also wasted time making useless requests to the judge. Criminal justice expert Peter Vronsky suggested that advanced predatory instincts in serial killers are often mistaken for intelligence, via Oxygen. This is likely the case with Bundy.

His survivors have spoken up

There have been plenty of women who have survived Ted Bundy's horrific crimes and have gone on the record. His first known survivor is Karen Sparks-Epley (pictured), who was beaten and sexually assaulted by him in her bedroom in 1974 while she was a student at the University of Washington. She was attacked with her own bed frame and lay helpless for 20 hours. Sparks was left with permanent injuries, including brain damage.

One woman's strange escape revealed Bundy's penchant for a certain type of female. Sotria Kritsonis was offered a ride by Bundy at a bus stop, and once she hopped in, he quickly made it clear she was not meant to make it out alive. He started yelling threats but suddenly demanded that she take off her hat. It's well known that Bundy's preferred victim profile, at least in his murder spree of 1974, was a woman with long, dark hair that is parted in the middle. Kritsonis may have fit that picture at one point but had recently gotten a haircut. Bundy, who likely had been stalking her before, was surprised at her new hairstyle and dumped her off at her destination.

He had a daughter while in prison

Ted Bundy and Carole Boone were not supposed to have conjugal visits while he was in prison, but they evidently happened anyway. In the documentary "Conversations With a Killer: The Ted Bundy Tapes," Boone said that the prison guards ceased to care about their acts of intimacy, although the couple didn't have much privacy (via Women's Health). It also wasn't uncommon in those days for prisoners to bribe guards so they could have sex with their partners. The result of these unions was Rose Bundy, Ted's only child.

She was born on October 24, 1982. Her early childhood was peculiar, to say the least. Her father was on death row, awaiting the electric chair, and she would pay him visits with her half-brother. Photos can be found of the small family huddled together, including an infant Rose. The familial bliss, if you can call it that, came to an end when Boone divorced Bundy in 1986. When Bundy was executed in 1989, Rose would have been about 7 years old. She has led a private life ever since.

If you or anyone you know has been a victim of sexual assault, help is available. Visit the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network website or contact RAINN's National Helpline at 1-800-656-HOPE (4673).