Here's Where You'll Find The Grave Of Robert E. Lee

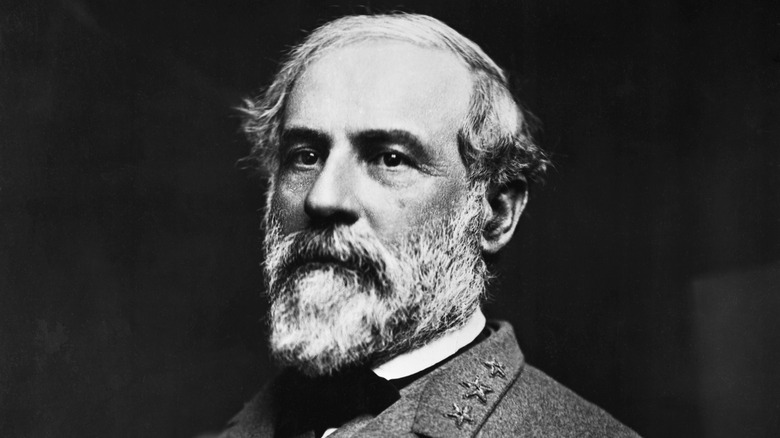

Robert E. Lee cuts a strange figure in American history. For a good part of the 20th century, his reputation was one of honor, chivalry, tactical genius, and graceful surrender. All this praise for a man who was not only a traitor, but leader of a traitorous army that sought to perpetuate slavery. His is a contentious legacy that has been debated and shifted in recent years as monuments to Confederate figures have been scrutinized. The Atlantic laid out a damning reassessment of Lee in 2017, the Richmond Times-Dispatch clung that same year to an image shaped by his better qualities, and Lee's descendants summed him up as "complex" to The New York Times.

Lee himself may well have been surprised and dismayed by all the fuss made about him after his death. He was against public memorials honoring the Confederate cause, and against statues to himself. Yet his final resting place is marked by a dramatic, life-sized marble statue above the crypt that holds his remains. That place is the University Chapel of Washington and Lee University in Lexington, Virginia, where Lee served as president after the Civil War (per Encyclopedia Virginia). After his death in 1870, he was interred in a brick vault in the basement; per Washington and Lee University, he was moved in 1883 when the chapel was expanded to include a mausoleum with a crypt. Lee's wife, children, parents, and other relatives have since been reburied in the same tomb.

Lee's final resting place was built at his request - but not as a tomb

It was Robert E. Lee himself who proposed the building that would be his tomb, though he didn't intend it for that purpose. According to Ty Seidule's "Robert E Lee and Me: A Southerner's Reckoning with the Myth of the Lost Cause," Lee considered "character," or moral development an essential component of a good education, and he felt the strongest force shaping moral development was religion. Determined to make gentlemen of his students, Lee saw mandatory church attendance end during his time as president of Washington College (as Washington and Lee University was then named), but he hoped that his personal example of regular church attendance would inspire others, and he wanted a chapel large enough to house the whole student body.

Washington and Lee University's history page on the chapel suggests Lee's son, George Washington Custis Lee, as the man behind the design of the chapel; Encyclopedia Virginia suggests that Colonel Thomas Williamson was the primary architect. Either way, the chapel was dedicated in 1868, and Lee was there every day. He worshiped in the morning and worked from an office basement, as did the college treasurer. His office has been preserved to this day, with the rest of the basement converted into a museum. The chapel — no longer big enough for every student on campus — is still used for memorial and funeral services.

Lee's widow had him buried at the chapel after 2 cities fought for him

While Robert E Lee had University Chapel built, it was his widow, Mary Custis Lee, who decided to have him buried there (per Encyclopedia Virginia). It wasn't a decision she was allowed to make quietly and privately. According to Ty Seidule's "Robert E Lee and Me: A Southerner's Reckoning with the Myth of the Lost Cause," two cities fought for the honor of being Lee's burial place: Lexington, home of Washington College (which quickly rechristened itself Washington and Lee University after the latter's death), and Richmond, capital of the Confederacy.

Richmond made the case to Mary that the greatest battles of the Civil War had been fought near its borders, that many of the Confederate dead were buried there, and that surviving soldiers wanted to see Lee alongside them, and that the city's Hollywood Cemetery held the graves of such notable men as President James Monroe. Lexington's case was that, as Lee had given so much to his college, they wanted him there always. Plans for the eventual mausoleum were first proposed at this time.

Lexington offered additional sweeteners, such as appointing the Lees' son George Washington Custis the new president of the university, and granting Mary a pension and lifetime lease on her house. The offers didn't work out well for Custis, who hated the job, but they satisfied Mary, who was in any event too infirm to consider moving at her age.

His funeral had weather and coffin trouble

Robert E. Lee's legacy to America has become an increasingly cloudy and stormy one for many historians; appropriately enough, his funeral was disrupted by clouds and storms. Per The American Civil War Museum, rain in Virginia was so heavy, and the roads so badly flooded, that it was impossible for any but local Lexington mourners to attend Lee's service on October 15, 1870.

Per Douglas Southall Freeman's "R. E. Lee: A Biography," the floods also interfered with preparing Lee's body for the earth. His coffins, brought to Lexington from Richmond, were swept out by the floods while en route. One of the caskets was recovered, but it ended up being slightly too small for Lee's body.

The mourners who did make it to the funeral were a mix of students and cadets from Washington and Lee University, Lexington locals, and former Confederate soldiers, many of them privates. No one wore the Confederate gray, however, nor did anyone carry a Confederate flag or drape a flag of any kind over Lee's coffin; by his express wish, the service was a simple one. Before he was buried in the chapel, the building he had commissioned was said to be overflowing with people.

Lee's tomb gradually became a shrine for Lost Causers

The marble statue of Robert E. Lee in repose that currently occupies the mausoleum of the University Chapel wasn't meant to be part of his tomb. Per Encyclopedia Virginia, it was commissioned a year after his death by the Lee Memorial Association and was sculpted by Edward Valentine. Once done, however, there was no ready home for the statue, and it wasn't until 1883 that it was taken in by Washington and Lee University for display in the chapel. That Lee had opposed such monuments doesn't seem to have been factored in by anyone.

Even before the statue and the mausoleum were built, the chapel was more associated with Lee than with its intended purpose. As Ty Seidule put it in his book "Robert E Lee and Me: A Southerner's Reckoning with the Myth of the Lost Cause:" "[Lee] attended daily worship services ... after he died, no Christian denomination held regular worship services in Lee chapel. The chapel worshipped another religion — that of Robert E. Lee." By the 1920s, it held a sacred aura for those committed to the Lost Cause myth of the Civil War. Something of that reputation still lingers in the nickname for University Chapel: the Shrine of the South.

Why wasn't Lee buried in Arlington?

Had the Civil War been avoided, or had Robert E. Lee remained loyal to the United States and fought in the Union army, he may never have been president of Washington College and buried there. His home before the war was Arlington, a hilltop estate near Washington D.C. that originally belonged to Lee's wife's family (per History). When Lee, after making his choice to resign from the Union army, was summoned to Richmond to receive a command (per American Heritage), he told his wife to leave their house. He correctly guessed that Arlington would be taken by the Union to prevent any attack on Washington from its high ground.

Arlington estate would, in time, become Arlington National Cemetery. It became so, in part, from an act of spite. Brigadier General Montgomery Meigs, who had once been a friend of Lee's, despised him for turning traitor. Meigs commanded the troops stationed at Arlington, and as Washington cemeteries became filled with the dead of war, he started having casualties buried on Arlington's grounds, so that the Lees could never return home without a reminder of the price of war.

Meigs became one of those buried at Arlington, albeit well after the Civil War, and the cemetery's reputation changed from a pauper's grave born of anger to a solemn, historical place. The Lees never did return there, and it's hard to imagine Lee's burial there, had it ever been in the cards, as appropriate. But his family did successfully sue to reclaim the house in 1874 — and promptly sold it back to the U.S. government (per the National Park Service).