The Scariest Part Of The Haunting Of Hill House Isn't The House

Debuting in October 2018, Netflix's 10-episode reimagining of Shirley Jackson's The Haunting of Hill House became a phenomenon for the streaming service, inspiring fan theories, online quizzes, and numerous attempts to find all the ghosts in the background. The series was entirely directed by horror filmmaker Mike Flanagan, whose previous efforts have included 2013's Oculus, 2016's Hush, and 2017's Gerald's Game, which has several cast members in common with Hill House. The result was a series that was not only popular with fans, but also widely critically acclaimed, with the Telegraph calling it "the most complex and complete horror series of its time."

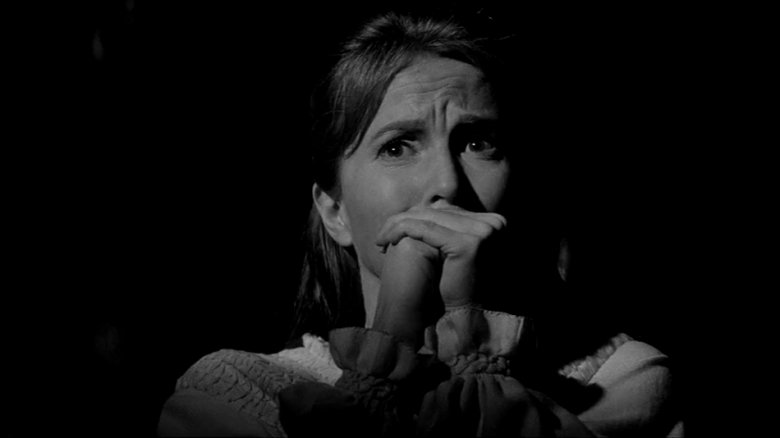

Besides the relatable nature of the various members of the Crain family so haunted by the titular Hill House, a lot of the success of the show comes down to the indelible imagery of its terrifying ghosts and specters, from the ominous Bent-Neck Lady to the menacing William Hill, floating around looking for his hat, to chattering flapper Poppy Hill and her talk of "screaming meemies." Visions of these ghosts torment the Crains, eventually driving them from Hill House, but even then not leaving them alone, affecting the children long into their adulthoods. But ghosts aren't real (Right? Probably?), so what is it in Hill House that we're really afraid of?

This article will, of course, include major spoilers for 2018's The Haunting of Hill House, and itty-bitty minor spoilers for the 1959 novel of the same name and the 1963 film The Haunting. Hold on to your hat.

The long history of the haunt

Haunted houses are baked into the very origins of horror film. In fact, the movie widely considered to be the very first horror movie is 1896's Le manoir du diable from director Georges Melies, released in the United States as The Haunted Castle. In this film's then-ambitious runtime of three minutes, two cavaliers enter a castle where they find themselves taunted and haunted by the devil, a skeleton, and some ghosts, all using state-of-the-art effects.

Since that time, as the Atlantic lays out, some of the most famous scary movies have played on the fear that the places we use as shelter, to protect ourselves from the elements and wild beasts and those who would do us ill, are maybe just as dangerous — if not more so — as simply lying on the ground in the woods. Movies like 1958's The House on Haunted Hill, 1961's The Innocents, 1979's The Amityville Horror, 1980's The Shining, 1980's The Changeling, 1982's Poltergeist, 2001's The Others, and more recent franchises like Paranormal Activity, The Conjuring, and Insidious all use the idea of a building full of ghosts to explore a wide variety of tones and themes. The idea that our very homes — where we should be safer than anywhere else in the world — can be full of dangers that assault us on not just a physical but metaphysical level is compelling enough that the premise is as popular as ever, as evidenced by the popularity of 2018's The Haunting of Hill House. But are spirits of the dead what really frightens us in Hill House?

Taking spookums seriously

Ghosts in the house weren't always a source of terror for filmgoers. While ghost stories by authors such as M.R. James and Sheridan Le Fanu were hugely popular in the Victorian era, the earliest haunted house films played the ghosts for laughs rather than thrills. Haunted houses as comedy can be found as far back as the ancient Roman play Mostellaria by Plautus, in which a young man pretends his house is haunted in order to keep his dad from finding out he wrecked the house with a party. Early haunted house films — including 1927's The Cat and the Canary and its 1939 remake, 1940's The Ghost Breakers, and, uh, 1941's Old Mother Riley's Ghosts — almost universally used ghosts (and/or cat-faced killers) for gags. Any spooks were usually, in a Scooby-Doo-like fashion, proven to be just as much the machinations of normal alive humans as the party ghosts of Plautus' play.

The major turning point was 1944's The Uninvited, which Criterion refers to as "an early example of a true cinematic ghost story — one that doesn't pull away the curtain at the end, Toto-like, to reveal a human manipulating the levers." The Uninvited uses real ghosts in a serious way to expose the damage done to a young woman's psyche by secrets and violence in her family's past. Such an earnest and emotional (and frightening) use of ghosts paved the way for such later masterpieces as 1961's The Innocents and, naturally, 1963's The Haunting, based on a certain novel by Shirley Jackson.

Hill House, not sane

Shirley Jackson, who is these days perhaps best known as the author of "The Lottery," a heavily anthologized story that is frequently read in classrooms, wrote The Haunting of Hill House in 1959, her fifth novel, and since then it has become, as the Wall Street Journal puts it, "widely regarded as the greatest haunted-house story ever written." The Hill House novel tells the story of a young woman named Eleanor Vance, who answers the summons of a paranormal researcher to spend the summer at a supposedly haunted mansion with the intent of witnessing and studying any supernatural occurrences that may pop up. Over the course of their stay, Eleanor and the other guests — the (probably lesbian) artist Theodora and the drunk young heir to Hill House, Luke Sanderson — experience funky phenomena such as unusual noises, strange writing on the wall, and various apparitions that nevertheless seem to center around Eleanor and the frustrations she feels about the family life she left behind to come to Hill House.

The book was brilliantly adapted to film in 1963 by director Robert Wise (who would later direct The Sound of Music and Star Trek: The Motion Picture, among other classics) and was definitely never made into a movie again, especially not in 1999 with Liam Neeson and Catherine Zeta-Jones. Wise's film effectively and chillingly depicts Eleanor's descent into madness while imbuing the whole house with an atmosphere of dread. These are the raw materials from which 2018's The Haunting of Hill House was formed.

I'm sorry, Ms. Jackson

Netflix's Hill House is not, strictly speaking, an adaptation of the novel. As director Mike Flanagan told Vulture, the novel's scope is not quite broad enough to fill a full season of television and so a considerable reimagining was in order. The events are moved to modern times (with flashbacks to about 25 years ago) and are now centered on the Crain family trying to flip the house rather than a quartet of paranormal researchers.

That's not to say the book is totally thrown out; lots of elements of the book make it into the Netflix series. Characters like Eleanor "Nell" Crain-Vance, Theo, Luke, and Hugh Crain all take their names and basic personalities from characters in the novel, while sister Shirley is obviously named after the author. Eldest brother Steve's writing is almost entirely actual prose from Jackson's novel, and a number of spoken lines in the show are direct quotes. Even smaller details such as the cup of stars and that ominous spiral staircase come from the novel or the 1963 film.

Most importantly, all three versions of this story have arguably the main character in common: Hill House itself. For Jackson, the house — personified as a body both irredeemably evil and utterly insane — is at the center of everything, inescapable, just as Eleanor's past proves to be inescapable. Likewise, the Crains have a difficult time leaving Hill House behind, as it follows them even as they flee it and go their different ways. Ultimately, however, the Crains have an advantage that Eleanor Vance does not.

Good grief

Dealing with grief and the lingering effects of trauma has been a major thematic element in modern prestige horror. As the New York Times points out, while grief is at the forefront of films like Hereditary and The Babadook, mourning the loss of a loved one can also be found in the DNA of such films as Get Out, Goodnight Mommy, A Quiet Place, Pyewacket, and It Follows. These movies use external supernatural or otherwise horrific elements to represent and literalize the internal damage done to their protagonists by depression, grieving, and loss, often of a beloved or even abusive parent. Evading the external threat usually means coming to grips with the internal scars left by this grief.

The Haunting of Hill House is no exception. The crisis point of each of its timelines is the apparent suicide of a beloved family member: matriarch Olivia in the flashback timeline, and youngest sibling Nell in the modern one. While Olivia's death in a way closes the book on that chapter of the Crain family's lives, Nell's death serves as the catalyzing agent for the present-day story, bringing the family back together after years of pain and strife have separated them, in some cases by thousands of miles. That so much of the present-day action takes place in Shirley's funeral home is no mistake: The Crains are a family that need to spend a lot of time processing their grief. After all, they're still coming to grips with their mother's death while at their sister's funeral decades later.

A stir of echoes

One of the most common uses of ghosts as metaphor is to think of them as echoes of the past, that the specters within the walls of a cobwebby old manor are in fact the specters of memory of past family trauma or violence. The ghosts of The Uninvited reflect a terrible crime that took place in that great cliffside home. The Eleanor Vance of Shirley Jackson's novel is haunted more by the lingering effects of her abusive mother more than any specific apparition in the house, and the ghosts of Netflix's Hill House are no different.

Near the end of the series, Steve lays out plainly that ghosts are the secrets, lies, resentments, and grudges that we carry with us in life. For example, previous owner and namesake of the house William Hill, we learn, was so tormented by the twin specters of guilt and fear that he bricked himself up in a wall before roaming the halls himself as a phantom as tall as he wished he could have been in life. Perhaps the most striking evidence that the ghosts of Hill House are more about emotional baggage is the way in which Shirley is haunted by visions of the man with whom she had an affair, whose status as a dead person we have absolutely no evidence for. If you don't need to be dead to be a ghost in Hill House, clearly something else is going on.

Popular because it's true

One of the more popular fan theories surrounding The Haunting of Hill House is that the five Crain siblings represent the five stages of grief, with the order of the stages reflected in their birth order, and hence the order of the first five episodes of the series, which each focus on an individual sibling. According to this theory, Steve represents denial, most notably highlighted by his skepticism about the very existence of ghosts or that anything preternatural happened in his old family home; Shirley is anger, and her resentment of her family members both living and dead reflects this; Theo is bargaining, using both her psychometric powers and her training as a psychologist to try to rationalize everyone and everything around her; Luke is depression, spiraling into a seemingly inescapable loop of substance abuse; and Nell is acceptance, who by the end of the series has come to terms with not only her mother's death, but her own.

When you put that lens on it, this theory seems so obvious in retrospect that you marvel that you hadn't considered it yourself and you feel that it must have been intentional. It probably won't surprise you in that case that director Mike Flanagan actually confirmed this theory on Twitter, referring to it as a "good catch." The Haunting of Hill House has more to say about grief than just, say, acknowledging it exists, and what it has to say on the subject is probably its biggest departure from Jackson's novel, even more so than turning paranormal researchers into squabbling children.

Love will tear us apart

The death of Crain matriarch Olivia is at the center of everything in The Haunting of Hill House. Everything in the flashback sequences builds up to it; everything in the present-day sequences is a reaction to it. Each child — plus their father, Hugh — has been uniquely scarred by this event thanks to their unique perspective on it and by what they did and did not see that fateful night in Hill House (and for Nell and Luke, in the Red Room). And subsequently, each of them tries to control their grief in their own unique ways.

Steve tries to process what he experienced through his writing and ghost hunting. While it seems like he's largely debunking the existence of ghosts, you also get the sense that he's desperately hoping for evidence that his family isn't crazy after all. He also notably tries to curb the spread of what he feels is his family's curse through getting a vasectomy that will, like a ghost, come back to haunt him. Shirley becomes a mortician to comfort families the way she was comforted. Theo becomes a child psychologist to help other children process grief so like her own. Luke of course tries to silence his visions with drugs, as fruitlessly as the man who gouged his own eyes out to stop his visions. Nell, for better or worse, uses therapy to deal with her feelings and lingering night terrors. Notably, no one turns to the others for solace. If anything, they do the exact opposite.

Whatever walked there, walked alone

When Theo is talking to her young patient who will later be revealed to have been abused by her foster father, she attempts to connect with the girl by explaining that the two are alike in that they are survivors: They build walls, you see, to make sure no one else can get in. What Theo doesn't yet realize at that time is that those walls are doing her and her family in.

The Crain siblings allow the loss of their mother and its fallout to drive them apart, putting up walls within themselves to close off their pain, fear, and guilt that are as real and terrible as the labyrinthine walls of Hill House filled with horrifying phantoms. Theo's isolation is the most literalized and visible of all of them, with her gloves that both remind her of her mother but also keep her from connecting with anyone else, except on her own terms. These walls of secrets, lies, and guilt take away the Crain family's strongest support structure — each other — in favor of an illusion of being in control. And worst of all, these walls kept ghosts in as much as keeping each other out, and they were directly responsible for Nell's death.

The scariest thing about The Haunting of Hill House isn't a roaming spookum in a bowler hat or a lady with a bent neck. It's the way we allow grief to convince us that whatever walked there — in fear, in guilt, in pain — walked alone.

Seven keeps you safe

In Jackson's novel, Eleanor Vance is never able to escape from Hill House because she is likewise never able to escape from the shadow of the abuse she has suffered at the hands of her mother and sister. Despite her best efforts to make connections with Theodora and Luke, her dreams of forming a new chosen family prove to be as ethereal and unattainable as the ghostly picnicking family she and Theo see on the Hill House lawn.

The Crains have an advantage in this way: They are already a family unit who, despite the distance among them brought on by the pain of their mother's death, have a foundation of love for each other buried somewhere in their memories. While it tragically takes the death of two more family members to remind the Crain children of what they once had, they are ultimately able to tear down the walls inside themselves that were harboring ghosts: Steve abandons the fear of his family curse and ends the secret he kept from his wife; Shirley forgives Steve and accepts his offer of help, plus admits her own missteps to her husband; Theo throws away her gloves and finally lets someone in; Luke stays clean with real support from his family.

In the end, while the potential of grief and pain to divide and isolate us can lead to despair and even a cycle of death and grief, our love and connection to friends and family — genetic, chosen, or otherwise — are what can tear down walls and exterminate the ghosts of fear and guilt. The rest, as Nell says, is confetti.