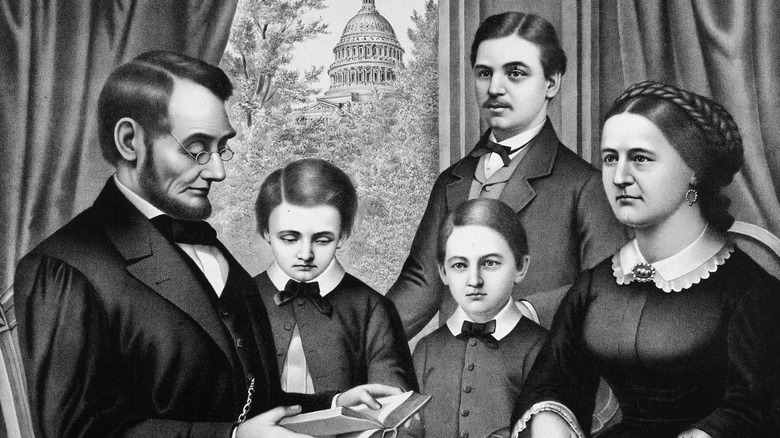

Whatever Happened To Abraham Lincoln's Kids?

There are some historical figures who loom so large in our collective mind that it can be difficult to regard them as fully human. Take Abraham Lincoln: The man has been so mythologized, has become such an icon of sober leadership and eloquent patriotism, that the archetype becomes all we know. It's easy to overlook the canny and complicated politicking Lincoln employed to preserve the Union and strengthen the federal government, and easier still to forget he was a man of good humor, a husband in a loving but difficult marriage, and a doting father.

Yet a father he was, to four sons: Robert Todd Lincoln, Edward Baker Lincoln, William Wallace Lincoln, and Thomas Lincoln (per the National Park Service). Lincoln's successive duties as legislator, congressman, and president often made him an absentee parent, but he and his wife Mary Todd were by all accounts loving and affectionate toward their children. They may even have erred on the side of spoiling their brood. Author Jean H. Baker wrote in "Mary Todd Lincoln: A Biography" that the Lincoln boys had a bratty reputation, and one of Lincoln's law partners found the boys so undisciplined and rowdy when they visited the office that he — hopefully in jest — declared that he wanted to strangle them (per "The Hidden Lincoln").

Such childish pranks gave way with time, and war, death, and mental health issues would further temper the Lincoln family over the course of the boys' lives. Here are the fates of the Lincoln children.

Robert Todd Lincoln

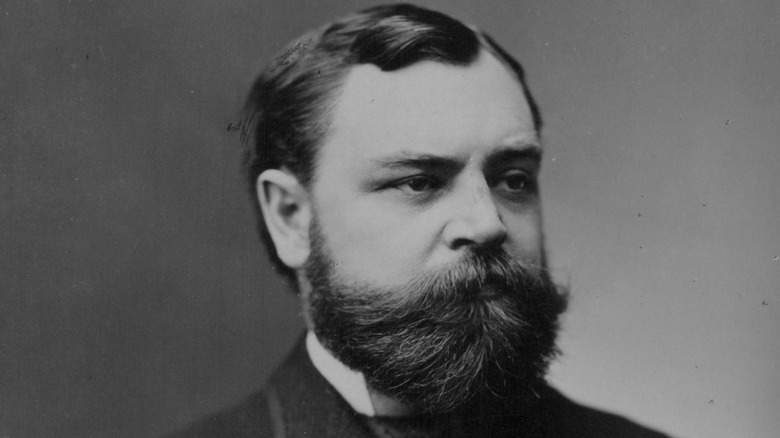

Among the many tragedies of Abraham Lincoln's life was that only one of his children lived to adulthood — his oldest, Robert Todd Lincoln. Born in Springfield, Illinois in 1843, Robert did not have a happy life. He claimed that his earliest memory was of his father waving goodbye as he left on business, and the two always had a distant relationship (via The Reagan Library Education Blog). Robert resented Lincoln's devotion to his political career, and he resented the attention that came from being the son of a public man (per Biography). Yet he was reportedly not above trading on his famous surname while studying at Harvard.

During the Civil War, Robert tried to enlist in the Union army, to his mother's horror. It's believed that she pressed her husband to secure Robert a position on General Ulysses S. Grant's staff, keeping him away from combat. He returned to Washington D.C. at the war's end and was at his father's bedside after his assassination. It was the first of three presidential assassinations he was associated with — he later witnessed the shooting of James Garfield and was outside the building where William McKinley was shot and killed. Ironically, Robert had once been rescued by John Wilkes Booth's brother from a train accident.

Though estranged from his father for much of his life, The Reagan Library Education Blog says Robert cried over Lincoln's dying body and followed him into politics. He was secretary of war to Garfield and minister to Britain for Benjamin Harrison, though he grumbled at times that he was only appointed to such roles for his name. He died in 1926 at the age of 82.

Edward Barker Lincoln

The Lincolns' second-born son, Edward Barker, is an enigmatic figure in American history on account of the short time he spent on this earth. Born in 1846, he was named for his father's friend Edward Dickinson Baker, per the Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Foundation. His childhood exploits became fodder for his parents' letters. Abraham Lincoln wrote about Eddy's (as he was known in the family) attempts to talk in April 1848 (per the University of Michigan Library). A month later, Mary Todd Lincoln wrote to her husband that Eddy became so attached to a kitten his older brother had found that he screamed at his step-grandmother when she tried to throw it out (per the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum).

Sadly, Eddy wouldn't live to reach his fourth birthday — he became seriously ill at the end of 1849. Historians have debated exactly what Eddy was sick with, but according to "The Black Heavens: Abraham Lincoln and Death," the consensus opinion is tuberculosis. He died February 1, 1850, to his parents' great grief. He was initially buried in a cemetery near the family home, but his remains were later interred with those of his father and brother in a family tomb in 1871.

In memorial of their son, the Lincolns had a poem, "Little Eddie," run in the Illinois State Journal. It remains a mystery who the author of this poem was. Per the Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association, despite longstanding speculation that one or both of the Lincolns wrote it, evidence points to it being the work of St. Louis-based poet Ethel Grey.

[Featured image via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled]

William Wallace Lincoln

William "Willie" Wallace Lincoln's namesake wasn't the famous Wallace of Scottish history, but his mother Mary Todd's brother-in-law (per the National Park Service). He was born in 1850 in Springfield and, according to the Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Foundation, took after his father more than his older brothers in temperament and personality. Abraham Lincoln reportedly recognized the similarity. With the expansion of American railways, he was able to travel home more frequently and take a larger role in Willie's upbringing than he had in Robert's, and the two grew close.

If the other Lincoln boys could sometimes provoke ire outside the family, Willie seems to have been a well-loved child. He was studious, religious, well-mannered, and kind. These traits didn't stop him from sometimes getting into trouble with his little brother Thomas, but he was the more conscientious of the two, and more comfortable with his father's duties and fame than Robert had been. He and Thomas were showered with gifts from the public after Lincoln became president.

From being the pride and joy of the Lincolns, Willie became their great personal grief during the Civil War. Per The Washington Post, he died in February 1862 after a short bout of typhoid fever. "He was too good for this earth. ... I know that he is much better off in heaven, but then we loved him so. It is hard, hard to have him die!" Lincoln said after Willie's death. Mourners were struck by how the loss affected the president, who never fully recovered from Willie's death before his own.

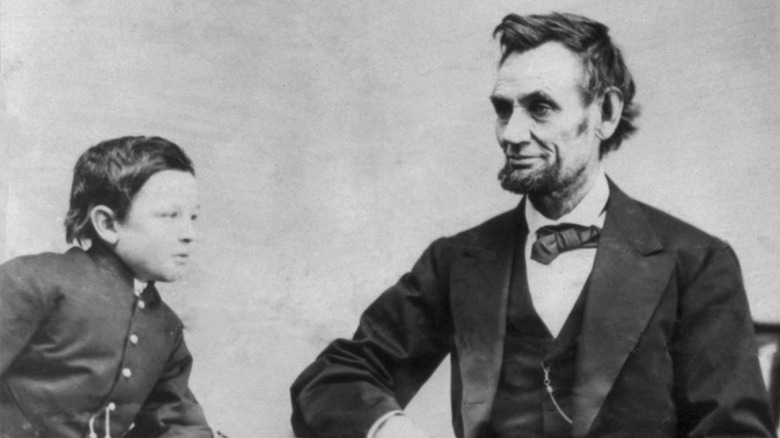

Thomas Lincoln

Britannica called Thomas "Tad" Lincoln, the youngest of the brothers, Abraham Lincoln's favorite child. He was certainly an indulged one. Born in Springfield in 1853, he was named for Lincoln's father and nicknamed Tad by the future president for his squirmy nature as a baby — "wiggly as a tadpole," as Lincoln put it (per the National Park Service). According to the Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Foundation, Tad was rambunctious and mischievous as a child, and while he could be affectionate with his family, his pranks and outbursts made him difficult for tutors, secretaries, and the White House staff, and his influence could induce older brother Willie into joining in on the mayhem.

It's been speculated that Lincoln was so lax in disciplining Tad because his youngest son had a speech impediment. Per the Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association, Tad had a cleft palate and may have had language and developmental articulation disorders. He also came down with typhoid fever at the same time Willie did. According to the National Park Service, some believe the loss of the older boy and Tad's recovery might have made Lincoln even more indulgent of his youngest child's behavior.

Tad was the only of Lincoln's children besides Robert to outlive their father. He was attending "Aladdin and the Magic Lamp" in another theater when Lincoln was assassinated at Ford's Theater. After his father's death, Tad reportedly faced his prospective future with maturity, though he still struggled to read and write. After several years of traveling Europe with his mother, he became ill on his return to the United States in 1871 and died — most likely of tuberculosis — in 1871. He was 18.

Mary Todd Lincoln had a complicated relationship with her sons

With Abraham Lincoln's long absences from home during his congressional years, Mary Todd Lincoln was their children's primary caregiver. Per Jean H. Baker's "Mary Todd Lincoln: A Biography," she was even more indulgent a parent than Lincoln was. True to her general disposition, she would sometimes lose her temper with her children, but she forgave easily, and even her harshest critics considered her an attentive and loving mother.

But Mary Todd's relationship with her sons became complicated as they grew and suffered tragedies. Willie's death left her in such a despondent state that, according to The Washington Post, Lincoln feared that she might need to be hospitalized in an asylum. She and Tad grew exceptionally close after Lincoln's assassination, but Mary fretted over his learning difficulties. When they went abroad, Tad became more of a protector and caregiver to his mother (per the Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Association); in letters back home, Mary would say that he reminded her of his father.

Her most difficult relationship was with Robert. Per the Reagan blog of the U.S. National Archives, they grew estranged after Lincoln's assassination. Mary's increasingly erratic behavior after the loss of three sons and her husband worried Robert, and he had his mother committed to an Illinois asylum in 1875. Per Biography, this was on the advice of her doctors, but Mary resented his actions and took to the press and the law to confirm her sanity and win her freedom. She and Robert kept a frosty relationship until her death in 1882.