Times Narcos Lied To You About What Really Happened

Netflix's Narcos has probably been responsible for teaching more Americans about Colombian history than decades of Discovery documentaries combined (and the same for Mexico with its spinoff Narcos: Mexico). A deep dive into the murky world of the war on drugs, Pablo Escobar's Medellin cartel, and the power plays at the top of Colombian politics in the '80s and '90s, Narcos is famed for its commitment to historical accuracy. Although showrunner Eric Newman has always been careful to stress that the narrative is condensed and refined to work as fiction, there's no doubt Netflix wants you to take Narcos seriously as television.

And serious is exactly what Narcos is ... until you go digging into actual Colombian history and find out just how much Narcos distorted, or exaggerated, or just plain made up. While some of these tweaks are minor, others are like watching a "historically accurate" Lincoln biopic open with Honest Abe taking part in a shirtless rap battle. Narcos is definitely great TV. It ain't so great at accurate history. So, so many spoilers below...

Escobar's real romantic appetites were way creepier

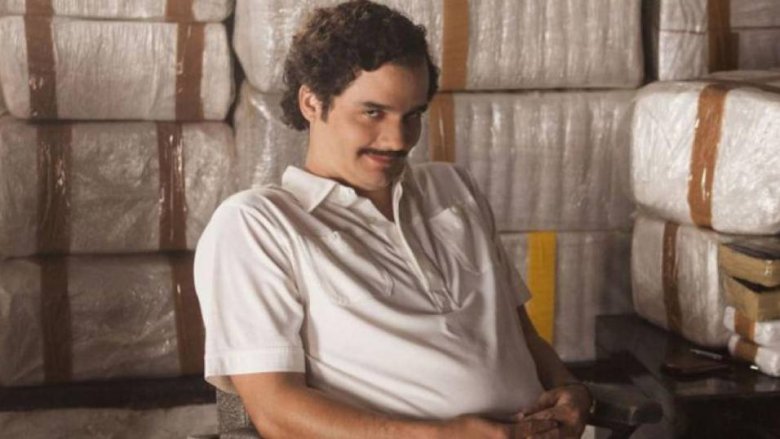

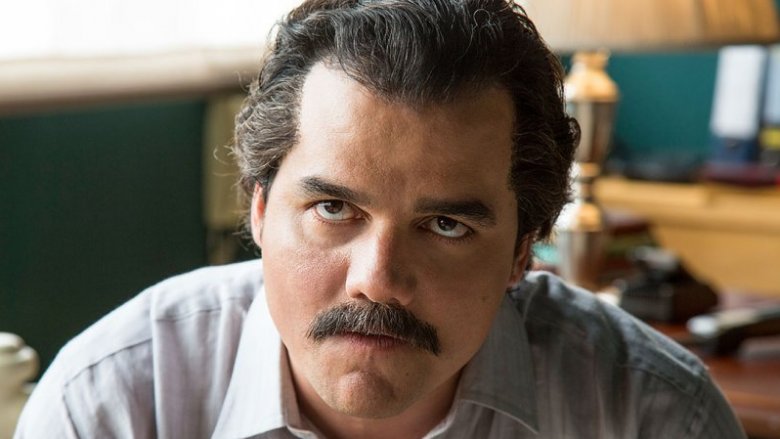

From the get-go, Narcos makes one thing clear about its version of Pablo Escobar. This is a big, crazy guy with big, crazy appetites. As played by Wagner Moura, Narcos' Escobar is a guy who wants power, pleasure and money, and will go to horrific lengths to obtain them. Fittingly for such a man, Escobar's romantic appetites are shown as equally large. When he's not busy bedding smoking hot reporter Valeria Velez (a fictionalized version of Virginia Vallejo), he's surrounded by surgically enhanced prostitutes flown in direct from Brazil.

The real Escobar was indeed a guy who liked the ladies. Or should we say, he liked the girls. According to the Daily Beast, Pablo generally wasn't inclined toward more experienced women. He prefered teenagers and underage virgins, and would throw wild parties featuring girls who were way too young to have ever had sex before. Sometimes, he would have them all murdered afterward. One party in the 1980s ended with Medellin police discovering the abused bodies of 24 teenage girls.

This disgusting habit infected Escobar's home life, too. Narcos portrays his wife Tata as young and inexperienced, but it doesn't make much of the fact that the real Tata (known as Maria Victoria) was only 15 when they married. The age of consent in Colombia is 14, but still. Eww.

The real Palace of Justice siege was even crazier

The fourth episode of Narcos centers around one of the major incidents of the Colombian civil war: the 1985 Palace of Justice siege in Bogota. In the show, Escobar needs some records destroyed, and offers rebel group M19 piles of cash to attack the palace and burn the records in the confusion. It's an interpretation that leans heavily into a popular conspiracy theory regarding the assault, but it's also one that leaves out many key facts. The most important one of all may be that it was probably the Colombian military that started the fire.

Vice has the full story. Rather than doing so under Escobar's orders, M19 attacked the Palace of Justice after President Betancur violated a ceasefire agreement with the group. Thirty guerrillas took over 300 people hostage, and the Colombian military responded by attacking the building. Tanks blasted the palace with shells. Rockets were used. Colombia Reports notes the fire that destroyed Escobar's records likely came from military rockets. In the aftermath, most of the M19 survivors were tortured and executed.

Nor did the tortures and executions stop with M19. The soldiers that stormed the building disappeared and murdered 12 cafeteria workers they wrongly suspected of supporting the guerillas. The whole traumatic siege took around 120 lives, with many Colombians today still blaming the authorities.

Colonel Carrillo of Search Bloc wasn't a real person (and no one died like he did)

Halfway through Season 2, Narcos pulls possibly its most brutal twist of all. Colonel Carrillo (above) is called back from exile in Europe to head up Search Bloc, the elite unit created to take down Escobar. A guy who isn't afraid to use the narco terrorists' own tactics on them, he's the dark side of the law but also the best chance at catching Escobar. Until, that is, a convoy he's in is dramatically ambushed on the streets of Medellin. His men gunned down, Carrillo is finally shot through the head personally by Pablo Escobar.

It's a dramatic, intense scene. It's also total fiction. In real life, not only did no Colonel Carrillo ever exist, but no one in Search Bloc ever died in such an ambush (via Daily Beast).

The real-life Colonel Carrillo was Colonel Hugo Martinez. If that name sounds familiar, it's because Narcos introduced him as a character in his own right in Season 2, quite possibly so they could have Carrillo do stuff that might have otherwise brought a lawsuit down on their heads. Martinez is still alive today, but Narcos was right that Escobar tried his damnedest to murder him. In April 1990, the Medellin cartel blew up the Martinez family apartment. Standing in the ruins of his home, the real Martinez was offered $6 million to stop fighting Escobar. He turned the money down.

M19 weren't killed off by the Medellin cartel

Narcos has a funny relationship with Colombia's insurgent groups. ELN barely shows up, and FARC is portrayed in Season 3 as little more than a bunch of farmers living in the jungle (rather than an insurgent army that once controlled a third of Colombia). But no other group has been portrayed so oddly as M19.

In the show, M19 is a small group of well-meaning students who mistakenly try to play with the big boys of the Medellin cartel and wind up getting shot dead by Escobar's men after the Palace of Justice siege. In real life, they were a feared fighting force of nearly 2,000 that disarmed under a government peace plan.

The Associated Press reported on the peace deal. In 1990, President Vargas and M19's leadership signed a deal to hand over the group's weapons. This was seen as a coup for Vargas. At the time, M19 were considered a bigger threat than ELN, and maybe even more so than FARC. Narcos is right on one point, though. After demobilization, many M19 members were killed by cartels, including leader Carlos Pizarro Leongomez. But not all of them. Former M19 guerrilla Gustavo Petro is currently in the Colombian senate, having previously served as mayor of Bogota (via Colombia Reports). Sometimes, life is stranger than fiction.

Connie was really in the thick of it the whole time

As played by Boyd Holbrook, DEA agent Steve Murphy is the lynchpin of the first two seasons of Narcos. Arriving in Bogota with his wife, Connie, in tow, he initially clings to her as his lifeline to the real world, before parting with her in Season 2 when the threat to her life becomes too great. It's powerful stuff, and Connie's return to the U.S. with their adopted daughter is a great way of showing how the hunt for Escobar is leaving Murphy isolated and hollowed out. But it also does a disservice to the real Connie. In an interview with Hollywood Reporter, the real Steve Murphy explained Connie had stayed in Colombia the entire time.

To be clear, this was just as dangerous as it was for the fictional Connie. Escobar really had put a price on the heads of Murphy and his family. But Connie stayed in Bogota even in the last, desperate 18 months that Search Bloc was tracking Escobar through the slums of Medellin. According to Murphy, she got upset when she read her character was being written out. Hollywood Reporter quotes her as saying of Escobar-era Colombia, "I would have never left my husband there!"

The real agent Pena wasn't involved with taking down Cali

Narcos Season 2 ends with most of the major characters dead, in hiding, or with no conceivable reason to continue being in Colombia. As a result, the shift in Season 3 to the Cali cartel risked alienating viewers who'd been tuning in to watch Murphy and Pena take down Escobar. So the showrunners compromised. While Escobar remained dead and the fictional Murphy followed his real-life counterpart back to the U.S., Pedro Pascal's agent Javier Pena returned for Season 3 to take over as the lead character. As you can probably guess, this is the exact opposite of what really happened.

As Biography describes, the real Pena had nothing to do with taking down Cali. Showrunner Eric Newman put it like this: "we've sort of put Pena as our one continuous character and made him representative of the DEA and the management in Colombia at the time," which is producer speak for "yeah, it's all bull poop, but it's poop that makes excellent TV!"

That's not to say everything Pena does in Season 3 is fiction. The showrunners used him as a useful receptacle for stuff many DEA agents did at the time. Most notably, this includes Joe Toft, who really did go on the record in September 1994 to call Colombia a "narco democracy" and accuse President Ernesto Samper of being bought and paid for by the Cali cartel (via UPI).

Miguel Rodriguez's son is still alive (and mighty annoyed)

The shift in Season 3 to the Cali cartel saw a whole slew of new characters added to Narcos' roster. Among the most prominent was David, the violent son of Cali godfather Miguel Rodriguez. In Narcos, David spends the whole third season looking like a time bomb that's one hair trigger away from exploding. But when it finally happens, the show pulls another rug out from under us. Just as David is storming out into the streets in the final episode, looking for vengeance on those who betrayed his father, he's gunned down by a rival cartel. He dies then and there, lamented by no one.

For William Rodriguez Abadia, watching that scene must have been a surreal experience. The real son of Miguel Rodriguez, William not only didn't die in a hail of bullets but according to the Miami Herald, is also mighty annoyed Narcos thinks he did. Like the fictional David, William was involved in the family business. But while David wanted to be his father's muscle, William was a lawyer who stayed away from the grisly side of cartel life. While he admits he bribed politicians, and spent five years in a U.S. jail for drug trafficking, he disputes ever carrying out any murders. Still, it's hard to feel sorry for a guy who once helped his father run a drug empire even larger than Pablo Escobar's.

We don't actually know who killed the real Navegante

After spending two seasons lurking around looking menacing, Juan Sebastian Calero's Navegante emerged in Narcos' third season as a brutal hit man with a love of intimidation, torture, and other things that would be a major no-no on your average Tinder profile. His death at the season's climax, though, was handled strangely. With the Cali cartel falling apart at the seams, mole Jorge Salcedo is forced to return to the city where everyone wants him dead. Caught sitting in a car by Navegante, the two have a creepy chat before Navegante pulls his gun ... and is instead blown away by Salcedo, who does a Han and shoots first.

It's probably Narcos' most Hollywood moment, and it feels weirdly out of place in a series that otherwise prides itself on being realistic. So it's no surprise to learn it never happened. Speaking to Hollywood Reporter, real-life DEA agent Chris Feistl explained that Salcedo was holed up in fear of his life when the real Navegante died, and we still don't know who pulled the trigger.

In reality, Navegante was a guy called Cesar Yusti, and he was probably as violent as his fictional version. According to the real Jorge Salcedo, Cali's hit men would do things like pull people apart using two vehicles driving in opposite directions. Gee, who would want to kill such a fine, upstanding citizen?

Murphy wasn't on the scene when Escobar got iced

The finale of Narcos Season 2 is the culmination of two years of storytelling. In 1993 Medellin, the DEA and Search Bloc finally trace Escobar to a small apartment. As the godfather of cocaine tries to escape across the rooftops, agent Steve Murphy gives chase. He's there to witness the sniper shot that leaves Escobar badly wounded, and also to see a member of Search Bloc shoot the drug lord dead in cold blood.

Thematically and narratively, having Murphy right there when Escobar is finally eliminated makes perfect sense. Historically, not so much. While the show is right to say the real Agent Pena was out the country when Escobar was finally taken down, the real Murphy was miles away from the action. According to a 2017 interview with Javier Pena, Murphy was at headquarters when a major came by to tell him "viva Colombia, Pablo is dead!" Although Murphy was sent out to ID the body — at which point he took his infamous photo of Escobar's corpse — Pablo had already been dead for a while when he arrived.

Murphy's presence isn't the only thing off with Narcos' portrayal of Escobar's death. In real life, we have no idea who fired the lethal shot. There are conspiracy theories pointing the finger at everyone from Search Bloc, to the Colombian police, to Escobar himself committing suicide (although that last one is unlikely).

The wedding bombing never happened

A critical turning point in Narcos' second season comes when the Medellin cartel detonates a bomb at a Cali cartel wedding party. This triggers a chain of events that winds up with Cali allying with right-wing paramilitaries and the wife of a dealer murdered by Escobar, Judy Moncada (Dolly Moncada in real life), to bring the war onto the streets of Medellin. In effect, the bombing sets up the creation of the very-real anti-Escobar hit squad Los Pepes, who terrorized the Medellin cartel from 1990-93. But while Los Pepes were fact, the wedding bombing itself was pure fiction.

In 2016, Sebastian Marroquin, the real-life son of Pablo Escobar, posted a lengthy Facebook rant where he identified 28 inaccuracies in Season 2 of Narcos. Among them was the bombing of Gilberto Rodriguez's daughter's wedding. While the words "son of Pablo Escobar" don't exactly make for impeccable truth-telling credentials, Marroquin appears to be right in this case. Type "Cali wedding bomb" into Google and all you'll get are discussions of Narcos rather than, y'know, actual history.

Interestingly, one extremely surreal attempted bombing was left out the show. According to the Guardian, the Cali cartel at one point hired a British mercenary to bomb Escobar's estate from a military attack helicopter. The assault only failed after the helicopter got lost in bad weather.

The Cali cartel's hidden homophobia

The only character to appear in all three seasons of Narcos plus Narcos: Mexico is the Cali godfather Pacho Herrera (above). Played by Argentinian actor Alberto Ammann, Pacho is openly gay, which becomes a plot point in Season 3. When the Mexican cartel offers Pacho the chance to turn on his old employers, Pacho turns them down, saying the Cali godfathers never ostracized him for his sexuality. It's a nifty way of highlighting the differences between the macho Medellin cartel, and the sophisticated, upper-class Cali.

In many ways, Narcos gets its portrayal of Pacho right. He really was gay, and the other Cali godfathers really didn't mind. But that's not because they were more urbane than Escobar's men. The real Cali cartel was poisonously homophobic. As the Daily Beast describes, they ran social cleansing operations in Cali that exterminated homosexuals.

Manuel Castells went into some depth in his book End of the Millennium. Cali's social cleansing gangs would track down gay people — alongside street kids and prostitutes — murder and mutilate them, then throw their bodies into the Cauca River with a sign tied around their necks that read "clean Cali, beautiful Cali." While Pacho's position meant he was immune from such treatment, he was the lucky one. At one point, so many undesirables were dumped in the Cauca that the cost of removing the bodies bankrupted a downriver municipality.

The real Murphy and Pena became celebrities

The death of Pablo Escobar marked the end of the line for agents Steve Murphy and Javier Pena. In Narcos, Murphy simply leaves Colombia and is never heard from again. Pena, meanwhile, goes and takes down Cali (which, as we've discussed, didn't happen), before retiring to his father's home on the Mexican border. Season 3 ends with him helping his dad fix fences and otherwise living a simple, small-town life.

Most of Narcos' poetic license is used to make real events more interesting, but not this time. Out here in the real world, Murphy and Pena's retirements were nowhere near as blissfully dull as in the show. The real agents became Hollywood celebrities.

It started almost as soon as they returned from Bogota. Hollywood Reporter explains how producers immediately approached them about selling their stories. While the movie pitches all leaned too heavily into glamorizing Escobar to fly with the agents, they did start doing speaking tours right up until they retired from the DEA in 2013. At that point producer Eric Newman had heard of them and invited them to chat about making the series that would become Narcos. With the subsequent success of the show, Murphy and Pena now travel the world doing press junkets and speaking to audiences of thousands. It may not be as narratively satisfying as having their characters go back to the simple life, but it's probably more lucrative.

Escobar never tried to shield his kids from his life of crime

Narcos is clear that Pablo Escobar is one bad dude. He kills people in cold blood, murders innocents, blows up an airliner, and generally does things so unambiguously evil that he makes Tony Soprano look like Santa Claus. But there is one area where TV Pablo is shown to have something like morals: his family. When Cali nearly kill Pablo's kids with a bomb outside their apartment, Escobar becomes like an avenging angel, enraged that his children are being dragged into his seedy business. But the real Pablo was way less of a family man than Netflix makes out. According to his own son, Escobar used to boast about his crimes and warn his kids they might become victims themselves.

Ahead of season two's premier in 2016, Juan Pablo Escobar sat down with Spain's El Pais to complain about the show. He took serious issue with his own depiction and stated that his dad was far crueler than Wagner Moura's portrayal. For example, the kids were always made to travel between safehouses wearing blindfolds. This wasn't to protect them. Escobar himself made very clear it was so if they were captured and tortured they couldn't give information on him.

Nor was Escobar shy about the family business. When his children saw news reports about horrific bomb attacks, Escobar would openly tell them, "I planted that bomb." Gee, it's almost like real-life narco terrorist psychopaths really don't have a conscience.

The Cali and Medellin cartels started out as brothers

The Cali and Medellin cartels in Narcos are both cocaine empires, but they have business models so different that it's almost like comparing JP Morgan to al-Qaeda. Medellin is macho and violent, just like the city they ship to (Miami). Cali, by contrast, is coke done NYC business style, with Pacho just as likely to take you golfing as he is to massacre your family. It's a way for Narcos to explore two different types of drug dealers, and it helps explain the animosity between the two cartels. But the real Cali and Medellin weren't so different. When they started out, they were practically brothers.

According to NACLA, Cali was the first major cartel to arise in Colombia, but it had no interest in being the only one. When Medellin appeared, the Cali godfathers actually helped them get bigger, creating what was almost a joint business. At one stage, they owned a bank in Panama together, and both were equally instrumental in the "Death to Kidnappers" project to hit back at guerrilla groups, which is something Narcos depicts as completely excluding Cali. The two only drifted when Escobar started attacking the Colombian state, something Cali worried would spark a confrontation they couldn't win.

In fact, Cali and Medellin were so close that they knew one another's operations intimately. This is what made the eventual war between them so brutal, as they knew exactly where to strike to inflict maximum damage.

The Castano brothers started out working for Medellin

Of all the psychopaths in Narcos, perhaps none are quite so psychotic as the Castaño brothers. A pair of ultra right-wing paramilitaries who turned to extreme violence after guerrillas killed their father, they turn up in season two determined to paint the town red. Quite literally. The number of people they kill in grotesque ways as part of Los Pepes is up there with any old school slasher movie. But while the basic outlines of the Castaño's backstory is broadly true, Narcos did miss out one crucial detail. The brothers didn't start life as regular Joes only to turn to violence after their father died. As younger men they were both members of the Medellin cartel (via New Republic).

This is very, very different from what the show portrays, which is a world where the Castaños are effectively a separate part of Colombia's troubles who get roped into the cocaine war. But Carlos Castaño was particularly familiar with the workings of Medellin. He'd been a sicario, or hitman, for the cartel back in the day, while his brother, Fidel, was a full member. Hence their effectiveness as part of Los Pepes. Like Cali, they knew where to hit to make Escobar squeal.

The paramilitary group the brothers led was also more extreme than the one seen in the show, if that seems possible. The US State Department once called Fidel Castaño "more ferocious than Escobar."

FARC: more than just farmers

Despite once being the biggest rebel group in Colombia, FARC is curiously absent from Narcos. The far smaller M-19 (pictured) gets far more attention, and when FARC does turn up in season three, the group is described as being made up of "farmers" who are good at kidnapping but otherwise a negligible part of the drug scene. While it's understandable Netflix would prefer to focus on the dramatic, sexy world of drug lords instead of the dramatic, sexy world of revolutionary Marxism, their depiction of FARC softens the group's image. Far from being just farmers, FARC at its height was actually comprised of a ruthless terrorist army that controlled one-third of Colombia (via Colombia Reports).

Formed in 1964, FARC started out as a gang of impoverished men who wanted to carve out their own state separate from Colombia. When Colombia's government dismantled this faux state with bullets, the farmers fled for the jungle. There they declared themselves in rebellion but didn't do very much ... until cocaine came along.

In 1982, FARC began moving into cocaine production and shipping, a move which saw its capacity as an army grow to crazy levels. Come the time season two is set, the group had nearly 6,000 active fighters. Eventually, this would grow to over 20,000. Nor were these just farmers wielding guns. FARC fighters were trained by both the Soviet Union and the IRA (via Telegraph). Basically, these were a scary bunch of guys, and it was their civil war against the government that gave Escobar space to flourish.

Jorge Salcedo's background is way shadier than it is in Narcos

After two seasons depicting all cartel members (not unreasonably) as murderers, Narcos decided to change things in season three with the character of Jorge Salcedo. The head of security for the Cali cartel, Salcedo is shown as a fundamentally decent guy trapped in a life of crime by circumstance and the need to protect his family. While his desire to go legit does feel like narrative shorthand for showing us he's not evil, the fact that he was a real person who really did take down Cali seems to suggest Narcos basically does a good job of portraying him. Well, apart from the bit where they miss out all his insane connections to paramilitaries, white supremacists, military hardliners, and his pre-Cali role in masterminding assassination attempts (via NACLA).

The real life Jorge Salcedo wasn't an innocent trapped in a morally gray world. He had family connections to the darker sides of Colombia's military, connections that saw him spearhead an attempt in the late 1980s to assassinate FARC's leadership. The operation involved Salcedo bringing together ruthless paramilitaries and mercenaries who'd previously fought for the white supremacist government in Rhodesia. Although the attempt failed, it was evidently impressive enough that it landed Salcedo on Cali's radar. Shortly after, he began advising the cartel on certain issues before graduating to their head of security. So, yeah, the one "good" narco from Narcos was actually as shady as his career would suggest. Who'd have thought it?

Colombian accents really don't sound like that

If you're a native English speaker, chances are you've never paid much attention to the accents in Narcos, beyond thinking, "Yep, that sure sounds like Spanish." Even if you're an actual Spanish person from Spain, you may have only clocked that the accents sound a little iffy. But if you're from Colombia? Apparently watching Narcos is like trying to watch an alternate-reality version of Downton Abbey where all the British characters are voiced by Mary Poppins-era Dick van Dyke. As The Guardian reports, the producers sourced actors from all over the Americas to play the Colombian characters. To their credit, these actors mostly attempted local accents. To Colombian viewers' everlasting disappointment, they mostly failed.

Warner Moura, for example, spent three months living in Medellin, trying to get the Escobar accent down. Instead, he wound up sounding like what he was: a Brazillian dude trying his hardest to speak in a regional Colombian accent and failing. This was an even bigger issue when you realize that the script absolutely nailed 1980s paisa slang, which, in Moura's Brazilian twang, now entered the uncanny valley. Per the Miami Herald, it undermined the effectiveness of crucial scenes.

But, hey, at least Moura tried. Luis Guzman, who played José Gonzalo Rodríguez Gacha in season one, just stuck with his Puerto Rican accent. None of this is a problem at all if you can't speak Spanish. But if you're a native speaker, it's the most glaring lie of all.

Pena never had a close alliance with Don Berna

Introduced in season two, Don Berna is a major player in the Medellin crime scene, despite never seeming to set foot outside his favorite cafe. Based on the real rebel-turned-drug-dealer-turned-paramilitary Diego Murillo Bejarano, Don Berna is portrayed by Mauricio Cujar as not just being connected to the narco-world but also having a long-standing relationship with Agent Pena. Unsurprisingly given the series' genre, that relationship is a classic informer/informant one, with Don Berna slowly feeding Pena information that benefits both the DEA, and psychopathic paramilitary group Los Pepes.

But while you might have assumed the alliance between Pena and Don Berna was fictionalized for the sake of narrative simplicity, you probably wouldn't have assumed that it was entirely made up. In 2016, The Hollywood Reporter spoke to the real Pena about Narcos season two. The former agent made it clear that he and the real Berna had almost nothing to do with one another.

According to the article, Don Berna's real-life counterpart really did work as an informant for Search Bloc while also feeding information to Los Pepes. But he and Pena barely set eyes on one another, let alone sat down for coffee. The reason is that Berna only had a relationship with Search Bloc itself and not the DEA. As real-life Pena put it: "We never signed him up as a DEA informant, but he was at the base and I could always tell there was something weird".

Escobar never visited his dad's farm

So, the penultimate episode of Narcos season two was weird, right? Y'know, the one where fugitive Escobar grows a beard and goes to visit that old peasant dude living on a farm ... only for us to discover the peasant is his dad, and then the two spend like 45 minutes fixing fences together? Well, one of the reasons it was so odd was because the writers did with the plot what any good mule would do with a condom full of Escobar's marching powder: They pulled it out their butts. As showrunner Eric Newman told The Hollywood Reporter when asked about the truthfulness of the episode, "That was invented in terms of the content." In other words, it was spun from cloth so whole it could keep Don Berna supplied with shirts for a decade.

The truth is that almost nothing is known about Escobar's last days on the run. He vanished off the grid, so any show that wanted to tell his story would be forced to make something up. As Newman points out in the interview, it's known that Escobar died before his dad, so it's entirely possible that something like what happened on the show is close to the truth. On the other hand, Pablo could've done literally anything while on the run. Maybe he headed into the countryside, or maybe he just sat around with Limón talking soccer and drinking lukewarm cans of Aguilla in a cruddy hideout. Who knows?

Escobar's real political career lasted way longer

It's a major turning point in Narcos, the moment when Escobar finally wins election to the Colombian Congress. Borrowing a tie, he goes to spend his first day as a representative, only to be denounced as a narco. Humiliated and enraged, Escobar symbolically removes his tie, storms out the building, and returns to his life of crime. It's a powerful moment, and it more or less really happened — the "more" part being that Escobar really did get elected to the Senate and really did get denounced, the "less" part being that his political career didn't last a single day. According to Biography, Escobar sat in the Senate for two whole years before being ejected.

The New Yorker has additional details. Elected in 1982, Escobar was allowed into the Liberal Party thanks to a corrupt senator named Alberto Santofimio. Once he took his seat, Escobar divided his time between splurging cash in Medellin and trying to get a treaty allowing the extradition of drug traffickers to the United States scrapped. Not that his fellow Congressmen were under any illusions: The justice minister, Rodrigo Lara Bonilla, publicly denounced him as a gangster.

But while in Narcos, the accusation is enough to make Escobar leave, in real life, he tried to turn the tables by accusing Bonilla of being a client of (irony alert) Colombia's cartels. It was only when a newspaper resurfaced his conviction for cocaine possession that Escobar finally got the Congressional boot.

Tata probably didn't try to talk Escobar into surrendering

One of the strengths of Narcos season 2 is that we know Escobar is living on borrowed time. We've all seen that photo of him dead on the Internet — the only question is what depths he will plumb before the bullet finally catches him. A central part of the drama is how this affects the characters around him, especially his young, naive wife Tata. As the walls start closing in, Paulina Gaitán's character finally breaks and tries to get her husband to see sense. She wants him to surrender and get a sweet deal, or at least take the family and leave Colombia for good.

As you've probably guessed, though, there's no evidence that Tata was anything but totally onboard with what Pablo was doing. As showrunner Eric Newman admitted: "Did she consider trying to get him to surrender? Probably not, but that felt like the kind of thing that we could do in the context of our story."

Of course, there's an open question as to how much of a willing accomplice the real Tata (Maria Victoria Henao) can be called, given that whole "married to Escobar aged only 15" thing. But the real Murphy at least felt she was a willing part of the narco lifestyle, telling The Hollywood Reporter, "She knew, just like his mother, what he was doing. She took full advantage of her husband's business. [...] She lived like a queen."