Every Baby That Was Born In The White House

No one asks a baby where it wishes to be born, but you would assume that given all the options and information, most would prefer a hospital. A less sterile but much cooler option, though, would be the White House. It's a select group of people who got this claim to fame, and while the exact number isn't certain (for reasons that will become clear), it's about twice as many people as those known to have died there.

None of the White House babies went on to be particularly famous, but the variety in their parentage and lives is fascinating. Some were born enslaved; one was born to a first lady. A few lived for a very short time, while others died on battlefields, and still others made it to their 90s. In a couple of cases, several siblings could claim to be White House babies. Here's the story behind every person who was born in one of the most famous buildings in the world.

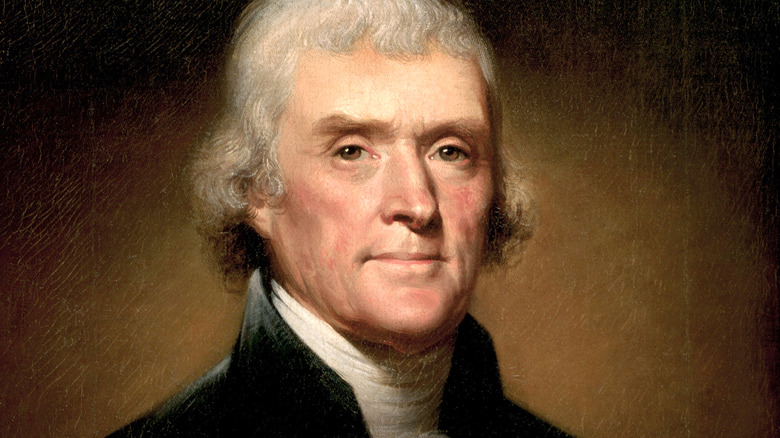

Asnet Hughes

The first child believed to have been born in the White House was Black, enslaved, and considered the property of the then-president of the United States, Thomas Jefferson, according to "Black Hands, White House: Slave Labor and the Making of America" by Renee K. Harrison. After he moved into the White House in 1801, Jefferson brought one of the people he enslaved at Monticello to Washington: a 14-year-old girl named Ursula Granger. The new president intended to have Granger study under the White House's French chef, so that his plantation would have someone trained in cooking fancy food.

However, this plan would not work out with Granger, as she gave birth sometime before March 22, 1802, about six months after she arrived in Washington. The father was Wormley Hughes, who had remained back at Monticello. It's not clear if they were married at this point, but they would eventually wed and go on to have another 12 children together. However, the baby born in the White House, a boy named Asnet, was not well.

Jefferson was away from Washington when his steward wrote him a letter (via the National Archives) on August 17, 1802. It contained sad news: "Sir, the poor little child Asnet died on the 14th of this month, but I assure you that the good Lord rendered a great service to him and to his mother, since he would have been infirm all his life." Ursula returned to Monticello shortly after this.

James Madison Randolph

Often claimed to be the first child born in the White House, James Madison Randolph was really the first white child born there. His mother was Martha Jefferson Randolph, the only child still alive of the then-president Thomas Jefferson and his late wife. Martha was pregnant when she, her husband, and their children moved into the White House in late 1805 to provide company and perform hostess duties for the widowed president, according to "Martha Jefferson Randolph, Daughter of Monticello: Her Life and Times" by Cynthia A. Kierner.

The Randolph family was still in residence when James arrived on January 17, 1806. While he was named in honor of Jefferson's fellow Founding Father and future president James Madison, he was not the first child in the Jefferson family with that moniker. Almost a year to the day before James Madison Randolph was born, his half-uncle James Madison Hemings was born at Monticello. The latter James was the son of Thomas Jefferson and one of the women he enslaved, Sally Hemings.

Shortly after his first birthday, one of James Randolph's sisters wrote to her president-grandfather: "James is very much grown and I think now is a very handsome and sprigtly child" (via the National Archives). He would go on to attend the University of Virginia — a school founded by Jefferson — before deciding to become a farmer. However, his attempt failed and he lost his farm within a few years. He was living with his parents when he suddenly became ill and died days later on January 23, 1834, aged just 28.

The enslaved Fossett children

Thomas Jefferson brought more than one enslaved girl from Monticello to train under the resident French chef, including the 15-year-old Edith "Edy" Hern Fossett, according to "The Invisibles: The Untold Story of African American Slaves in the White House" by Jesse J. Holland. Edy was pregnant when she arrived in Washington in 1802. The father, Joe Fossett, was also enslaved, and the couple endured a forced separation for most of the next six years. In January 1803, Jefferson recorded a payment to the doctor who attended when Edy gave birth, and also wrote to his daughter Martha Randolph that "Edy has a son, & is doing well" (via the National Archives).

However, in July 1806, the child became ill, most likely with whooping cough. News of the illness seems to have reached Joe at Monticello, at which point he ran away from the plantation to be with his wife and child in Washington, before being caught. This could have resulted in terrible consequences for the enslaved man, but he was not punished, possibly because Jefferson felt bad when their child subsequently died.

While they rarely saw each other, Edy and Joe did manage to have two other children while she was in Washington. James and Maria Fossett both lived to adulthood after being born at the White House. Edy and Joe had more children once she returned to Monticello; eight survived, including Peter Fossett (pictured). After Jefferson's death, only Joe was freed, while Edy and their children were sold. Eventually, Joe managed to buy freedom for Edi and five of their children.

The enslaved children of Fanny Hern

In 1806, enslaved 18-year-old Frances "Fanny" Gillette Hern was brought to Washington, D.C., by Thomas Jefferson to assist her sister-in-law Eddy Fossett in the kitchens. Fanny's husband, David "Davy" Hern, stayed at Monticello, which evidently put a huge strain on their marriage. However, they did see each other twice a year when he brought carts of supplies to the White House, giving Fanny opportunities to become pregnant. It's believed she had two children in the servants' quarters of the building.

Almost nothing is known about these children. According to the letters of Jefferson's contemporary, Margaret Bayard Smith (via The Library of Congress): "On one occasion when the family of one of his domestics had the whooping cough, he wrote to a lady ... requesting her to send him the receipt for a remedy, which he had heard her say had proved effectual in the case of her own children when labouring under this disease." It is thought this is in reference to Fanny's daughter, however, the remedy evidently did not work.

On November 7, 1808, Jefferson wrote to Edmund Bacon, the overseer of Monticello: "Be so good as to inform Davy that his child died of the whooping cough on the 4th. day after he left ..." (via the National Archives). Ten days later, Bacon replied, "Davy Has petitioned for leave to come to see his wife at Christmass. he being so Good a fellow. I hate to Deny him."

[Image by MPSharwood via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 4.0 DEED]

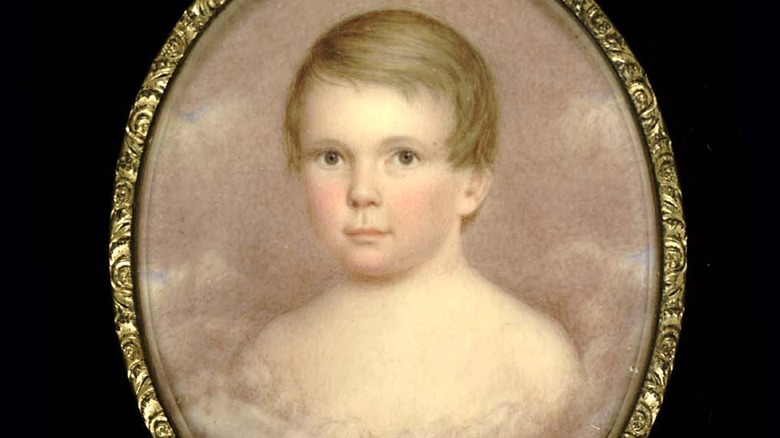

Mary Louisa Adams

In 1828, John Quincy Adams was president, and his son John Adams II was recently married. John's bride, Mary Catherine Hellen, ended up getting pregnant almost immediately. Her mother-in-law, Louisa Adams, was worried because Mary refused to get any exercise and complained endlessly. But the couple lived in Washington, D.C., with the president and first lady until Mary gave birth to a daughter, Mary Louisa Adams, in the White House on December 2, 1828.

While her mother didn't seem any more interested in her child than she was in her marriage — which was not a lot — Mary Louisa was doted on by her grandparents. Louisa took on much of the mothering role in the girl's life, even comforting her through the night while she was teething, according to "The Adams Women: Abigail and Louisa Adams, Their Sisters and Daughters" by Paul C. Nagel. John Quincy bought her everything from toys to Bibles to a silver cup for her christening that is now in the Smithsonian collection. It is also home to a portrait (above) commissioned when Mary Louisa was about 7 years old. John Quincy also spent a lot of time with his granddaughter; as she recorded in a diary she kept as a young girl, he regularly tutored her in math and languages.

Mary Louisa married William Johnson in 1853, and the couple had two children before she died on July 16, 1859, aged 30.

Mary Emily Donelson

Mary Emily Donelson was a grand-niece of President Andrew Jackson through his marriage to his late wife, Rachel. Recently widowed when he entered the White House in 1829, Jackson brought his nephew Andrew Jackson Donelson with him to act as his private secretary, and his wife Emily (pictured) and their young son, who was also named after the president, moved into the White House with them. Shortly after settling in, Emily realized she was pregnant with her second child.

Arriving on August 31, 1829, Mary Emily Donelson would claim for the rest of her life that she was the first baby ever born at the White House, which her position on this list clearly shows is incorrect. However, she had shown she wasn't concerned with accurate details of her birth from an early age, when, according to "Emily Donelson of Tennessee" by Pauline Wilcox Burke, around age 7 she changed her own name from what she had been christened — Mary Rachel — to Mary Emily. Not only was she a grand-niece of the then-president, but her godfather was future president Martin Van Buren.

Mary Emily stayed heavily involved in Washington politics, talked regularly with various presidents, and was appointed to positions in the Postal Service and the Treasury. In 1900, she published a book about Christmas at the White House, including a story about convincing President Jackson to hang his first-ever stocking one Christmas Eve.

John Samuel Donelson

The fact he was born in the White House on May 18, 1832 (some sources say 1831) was, amazingly, one of the least interesting things about John Samuel Donelson's life. Not only was he both a grand-nephew and godson of President Andrew Jackson, and the second child of the Donelson family born there, but he would go on to be the only one of his siblings present when Jackson died in 1845, according to "Emily Donelson of Tennessee," and the only one to attend his funeral.

John Samuel was lucky to survive his first year, since Washington, D.C., was suffering from a major cholera epidemic, and even some people connected to the White House fell sick. Soon the Donelson family fled the residence, at least temporarily, bringing their children to safety. While President Jackson wrote that John Samuel became ill around his first birthday, according to "American Lion: Andrew Jackson in the White House" by Jon Meacham, this was only due to teething issues.

In 1854, John Samuel graduated from Yale. When the Civil War began, he joined the Confederacy and served with a Tennessee regiment. In September 1863, his regiment fought at Chickamauga (pictured). While the Confederates would technically win the battle, it was a Pyrrhic victory, as they lost so many men that it ended up being the second-deadliest clash of the entire war. One of the casualties was John Samuel, who was about 31 or 32 when he died.

Rachel Jackson Donelson

Rachel Jackson Donelson, who came into the world on April 11, 1835, was the last child of Emily Donelson's four children, and the third of her siblings to be born in the White House. Perhaps because she was named for his late wife (pictured), whose full name, confusingly, was Rachel Donelson Jackson, President Andrew Jackson seemed to be especially fond of this new baby. He wrote to a friend, stating: "[she is] as sprightly as a little fairy and as wild as a little partridge ... indeed an interesting child" (via "Emily Donelson of Tennessee"). Her godfather was future president James Polk.

While Rachel was a robust baby, her mother's health was quickly deteriorating. After being unwell for many months, Emily Donelson died on December 19, 1836. She was 29, and her youngest child was not even 2 years old.

Later in life, Rachel moved to Texas, where she married, was widowed, and married again. She lived quietly, despite her association with the late president, and had no children. However, like her mother, she ended up being sick for a long time. Her condition finally became so serious that she decided to risk having an incredibly dangerous operation. According to "Andrew Jackson Donelson: Jacksonian and Unionist" by Richard Douglas Spence, after the procedure, she asked her sister (and fellow White House baby) Mary Emily, "I did not flinch, did I? Don't you think father would be proud of me?" She died not long after this, on March 22, 1888, aged 52.

Rebecca Van Buren

Martin Van Buren was president when the former first lady Dolley Madison played matchmaker for his son, introducing Abraham Van Buren to Angelica Singleton. She was a beautiful heiress from a prominent family, the perfect match for the eldest son of the president. The couple married in 1838 and, after a honeymoon in Europe, they moved into the White House, where Abraham was his father's private secretary, and Angelica acted as hostess for the widowed president.

By 1839, Angelica was pregnant. According to "Martin Van Buren" by Caroline Evensen Lazo, the president was excited the White House would soon echo with the pitter-patter of little feet. The baby, Rebecca Van Buren, was born on March 4, 1840. Tragically, both Angelica and Rebecca fell sick with an unknown illness shortly after. Angelica was able to recover, but little Rebecca died. There is a bit of confusion or disagreement about this tragedy, as some sources record Rebecca was six months old when she died, while The National First Ladies Library says she was only five days old, and the date on her gravestone indicates she would have been 24 days old.

While the loss was painful, Angelica got pregnant again almost immediately. A son, Singleton Van Buren (pictured), was born in June 1841, three months after his grandfather left the White House.

Letitia Christian Tyler

When the Southern states officially decided to become the Confederacy in Alabama in 1861, a journalist recorded the scene (via "The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War" by David J. Eicher): "All Montgomery had flocked to Capitol Hill in holiday attire. Bells rang and cannon boomed, and the throng — including all members of the government — stood bareheaded as the fair Virginian [Letitia Tyler] threw that flag to the breeze ... A shout went up from every throat that told they meant to honor and strive for it; if need be, to die for it."

Letitia Tyler, the woman at the center of this display of treason, was the granddaughter of former president John Tyler, and had been born in the White House 19 years earlier. Her father was Robert Tyler, a good friend of the author Edgar Allen Poe, and her mother was a former actress named Elizabeth Priscilla Cooper (pictured). As John Tyler's wife was an invalid, when Robert moved with his father to the White House to work as his private secretary, Priscilla took on the role of first lady. It was during this period, on April 13, 1842, that Letitia, named for her invalid grandmother, was born.

She lived to be 82, dying on July 22, 1924. She is buried alongside her youngest brother in Montgomery, Alabama, the same place she raised the first Confederate flag.

Robert Tyler Jones

A grandson of President John Tyler, Robert Tyler Jones was born in the White House on January 24, 1843. As a young man, Jones joined the Confederate side during the Civil War, and not only saw action at Gettysburg, but was part of the infamous Pickett's Charge (pictured) on day three of the battle. He described the event: "We had been lying on our faces in a broiling July sun for several hours, with the artillery playing over us, when the order came ... I will never forget the scene" (via "Armistead and Hancock: Behind the Gettysburg Legend of Two Friends at the Turning Point of the Civil War" by Tom McMillan).

According to an account published in "Confederate Veteran" in 1894, fellow soldier James T. Carter remembered Jones acting valiantly during the charge, picking up the flag of the regiment after the man holding it had been killed: "When Jones took the colors he was shot in the arm, but continued to advance until he reached the stone wall, where he leaped on top and waved the flag triumphantly. But he was again shot, and fell forward severely wounded."

Amazingly, Jones survived and was honored for his "conspicuous gallantry," per "John Tyler: The Accidental President" by Edward P. Crapol. He was present at Appomattox when General Robert E. Lee surrendered in 1865. Jones died on May 18, 1885, aged 52. His obituary incorrectly stated he was the only male child ever born in the White House.

Sally Walker

When James K. Polk became president, he brought a close male relative with him to the White House to serve as his private secretary, the same as many presidents before him. In Polk's case, it was his nephew, Joseph Knox Walker. And it was in the White House on March 15, 1846, that Joseph's wife Augusta Adams Tabb (pictured) gave birth to the couple's fourth child, Sarah "Sally" Walker.

In an article for the St. Louis Republic, reprinted in "The Knox Family" by Hattie S. Goodman, Sally wrote about herself as a young girl. She called herself "a little queen" who was devoted to the president so much so that she rather got in the way: As well as admitting to a habit of infiltrating cabinet meetings, Sally claimed the president was often seen trying to find someone he could hand the little girl off to, saying, "Won't you please keep Sally out of my room."

When another child was born at the White House decades later, Sally sent a letter to its mother, first lady Frances Cleveland, essentially as a hello from one White House baby to another. According to "Dear First Lady: Letters to the White House" edited by Dwight Young and Margaret Johnson, Sally explained how she was born: "... in 1846 ... on [former president Andrew] Jackson's birthday and in the room he occupied." She hoped the tradition would continue and that the latest child would "live to send greetings to some future baby of the White House."

Joseph Knox Walker Jr.

The second child of Joseph Knox Walker and Augusta Adams Tabb to be born in the White House, during President James K. Polk's administration, was a son, Joseph Knox Walker Jr., also known as Knox. He was born on December 9, 1847.

When writing an article about her childhood, reprinted in "The Knox Family" by Hattie S. Goodman, Sally Walker explained that while she might have been a little queen, her younger brother "was made a baby king" and that of all of their parents' 10 children: "Knox was the pet lamb of the fold." She also stated that some said Knox was the first boy born in the White House, a claim that was repeated in several other sources. The same claim was previously made about President John Tyler's grandson Robert Tyler Jones, although neither of the boys was the actual holder of that title.

On August 9, 1857, the Memphis Daily Appeal reported that Knox had recently died after falling off a horse. While it placed his age at 12 and a half, in reality, the boy was only 10 years old. Sally wrote that her mother never recovered from the death of this beloved son, and that the tragedy contributed to Augusta's own death less than two years later.

Julia Grant

While being able to say you were born in the White House is neat, only one person can add that they went on to be an actual princess. Julia Grant was born to President Ulysses S. Grant's son Frederick and his wife Ida Honoré on June 7, 1876. Her parents had been living with the president since their marriage two years previously. In her memoir, "My Life Here and There," published in 1921, Julia wrote of her White House birth: "...in a quiet room, its windows looking out under the great portico of the President's mansion, a first child was born, an unusually large girl, 13 pounds of chubby health — myself." During William McKinley's administration, Julia returned to the White House and the president showed her the location where she'd come into the world.

While Julia admitted not being old enough to remember much about her time living in Washington, she recounted the story of when President Grant brought her to an official event, with dignitaries greeting the large baby in the receiving line, and even kissing her hand.

Julia lived in Europe when her father held a diplomatic post, and it was there she met the Russian Prince Michael Cantacuzene. The couple married in 1899, had three children, and divorced in 1935. According to her obituary in The New York Times, Julia remained involved in politics and society, attending events regularly into her 10th decade, even after losing most of her sight. She died on October 4, 1975, aged 99.

Esther Cleveland

Grover Cleveland has several "first and only" presidential accolades: He was the first and only president to get married in the White House, to serve two non-consecutive terms, and while the inter-term birth of older sister "Baby" Ruth might have been a more famous event, it was Esther Cleveland (pictured far left) who was and still is the only child of a sitting president to be born in the White House. When her sister Marion arrived two years later, their father was still president, but that birth occurred in Massachusetts. (And while Jackie Kennedy gave birth while she was the first lady, she did so in a hospital.)

While Esther was famous for her place of birth — it was mentioned in many newspaper articles about her, including the one in The New York Times about her social debut when she was 19 — she actually only managed it at the last minute. A few months before, the president had secretly had an operation and was recovering away from Washington with his family. They only arrived back at the White House on September 1, 1893, according to "The Health of the First Ladies: Medical Histories from Martha Washington to Michelle Obama" by Ludwig M. Deppisch, and first lady Frances Cleveland gave birth exactly a week later.

In 1918, Esther married British Army officer William Sydney Bence Bosanquet at Westminster Abbey in London. She died on June 25, 1980, aged 86.

Francis Bowes Sayre Jr.

Francis Bowes Sayre Jr. was born in the White House on January 17, 1915. His mother, Jessie, was the daughter of President Woodrow Wilson. As a young man, Sayre went to divinity school and became an Episcopal reverend, which led to him serving as a chaplain on a ship during World War II. In 1951, he became dean of Washington, D.C.'s National Cathedral, a position he held for 27 years, and which gave him an important, if unofficial voice in U.S. politics.

While Woodrow Wilson is infamous for his racism — a fact even the President Wilson House organization acknowledges — his grandson at least attempted to make up for it with his emphatic and demonstrative opposition to segregation, which President Wilson had been instrumental in normalizing. He participated in the 1965 voting rights march in Alabama that Martin Luther King Jr. organized, and was also on the President's Committee on Equal Employment during the Kennedy Administration.

The dean was an early and loud critic of Senator Joseph McCarthy, saying, "There is a devilish indecision about any society that will permit an impostor like McCarthy to caper out front while the main army stands idly by" (via The New York Times). A decade later, Sayre spoke against the Vietnam War; he also served for three years as the head of the United States Committee for Refugees. Sayre retired in 1977 but lived until October 3, 2008. He was 93 when he died.