What It Was Like To Be At The March On Washington

Officially known as the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, the historic event on August 28, 1963 was a direct response to the racist and abhorrent violence faced by African Americans. The country was reaching a boiling point during this time; voting rights for Black citizens were consistently attacked, and despite the landmark decision of Brown vs. Board in 1954, many southern states still resisted public school integration. On June 12, just a couple of months before the march, prominent civil rights activist Medgar Evers was assassinated at his home in Jackson, Mississippi, by a member of the Ku Klux Klan.

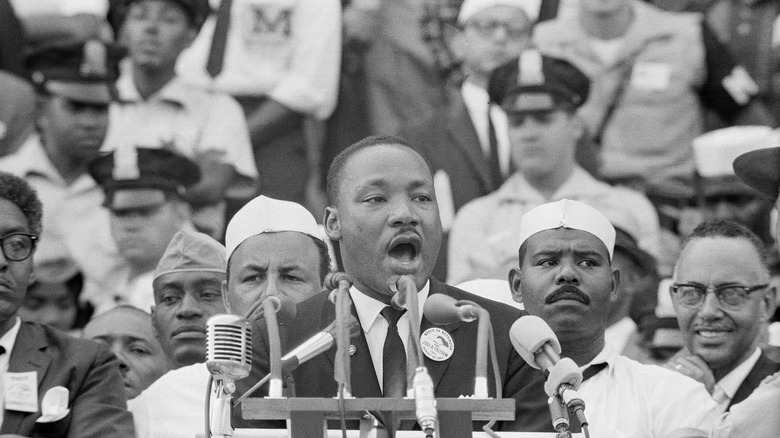

The March on Washington aimed to put a national spotlight on these issues and demand an end to segregation and greater federal government involvement on behalf of African Americans. Alongside Martin Luther King Jr., several other prominent voices spoke at the landmark event, including John Lewis, A. Philip Randolph, Rabbi Joachim Prinz, and Roy Wilkins, to name a few.

While many refer to the speech given by Martin Luther King Jr. as a pivotal experience during the march, there was much to be taken away from the day that was truly a watershed moment in American history.

The journey to Washington should not be minimized

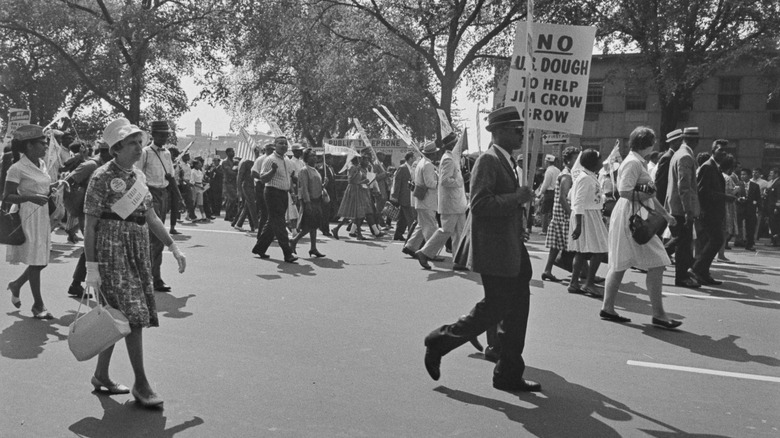

The March on Washington saw thousands of Americans from across the country travel to D.C by bus, car, plane, and train. A demonstrator from New York described how busy the roads were on the way to the capital, mentioning that the New Jersey Turnpike was filled with buses, all bumper-to-bumper, all heading to the same place (via The New York Times). Numerous other accounts tell similar journeys; the day of the march saw endless traffic around D.C., with countless buses filled beyond capacity arriving at the capital.

Over the years, Robert Avery's story has been famously recounted. The then 15-year-old hitchhiked to the nation's capital all the way from Gadsden, Alabama, with two friends. The journey was especially harrowing; just a few months before the march, William Moore, a white civil rights activist, was murdered only a few miles from Avery's home. He and his friends trekked on the same road where Moore was killed.

The travel to D.C. was not an easy task. Many Americans sacrificed their security and financial stability to participate in the March on Washington. Courtland Cox, who was 22 and worked with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee at the time, explained the situation to The Washington Post: "You're talking to people [for whom] bus fare was a week's wages. Or even more. People who came from the South had to do a great deal of sacrificing plus run a gantlet of terror."

It was a hot summer day

The weather in D.C. on August 28, 1963, was around 83 degrees. While not the most extreme summer heat, humidity was still a factor, and many participants arrived in the capital dressed nice. And, with all the moving involved that day, it didn't take long for demonstrators to be affected by the day's weather. By the time the speeches began, scores of spectators were experiencing extreme discomfort. The Red Cross had to treat around 1,335 people that day.

In his 2011 book, "Nobody Turn Me Around: A People's History of the 1963 March on Washington," Charles Euchner wrote that one marcher from New York, 56-year-old Charles Schreiber, suffered a fatal heart attack after reaching the Lincoln Memorial. Boston journalist Al Hulsen reported seeing multiple people near the Lincoln Memorial being lifted over the fence and taken to first aid, as per Smithsonian Magazine. Describing the severity of the heat combined with the compact throngs, Euchner noted, "Some passed out in the dense crowd and got passed above the crowd like hot dogs at a ball game."

Not everyone could hear the famous speeches

Martin Luther King Jr.'s "I Have A Dream" speech is one of the most lauded speeches of the 20th century and arguably the most studied aspect of the March on Washington. However, according to several personal accounts of those who attended, hearing King's historic words was either incredibly difficult or downright impossible.

In an interview with USA Today, Lyda Peters, who attended the historic event when she was 19, explained how unbelievably proud she was to have experienced the inspirational occasion firsthand. However, she admitted that she could not hear King or any other speaker due to being so far back in the crowd.

In 2013, The Nation interviewed several people who participated in the march. One man said listening to the speeches "was pretty tough to do because we were way in the back and the acoustics were terrible. Sadly, I don't remember Dr. King's great 'I have a dream' speech." Faulty audio equipment is a recurring theme amongst those who attended. The sound system reportedly cut out during King's speech, and spectators standing far from the Lincoln Memorial had to rely on transistor radios in order to listen to what was being said, according to Charles Euchner in his book.

Food and logistics were planned perfectly

From a pragmatic perspective, the March on Washington was a logistical marvel; any event that can take care of 200,000 people gathered in a single location has to be considered a rousing success. The organizers behind the historic occasion made exhaustive preparations to make sure everyone was fed, hydrated, had access to basic medical attention, and that there were plenty of portable restrooms available.

According to the Smithsonian, when it came to feeding the demonstrators and securing transport and other logistics, the numbers were staggering: 80,000 boxed lunches (that cost $.50), 2,200 chartered buses, 40 special trains, 22 first-aid stations, eight 2,500-gallon water-storage tank trucks, and 21 portable water fountains.

In another article, Smithsonian Magazine also notes a shocking five tons of American cheese went into the lunches brought down to the capital via refrigerated trucks. After enduring such long travel on bus and train, participants from all across the country were greeted with "roasted chicken, pies, cakes, stale coffee, and sandwiches," wrote Charles Euchner in "Nobody Turn Me Around." The march organizers paid such close attention to the type of food that would be prepared that they made sure to avoid mayo in anything.

Food wasn't the only logistical hurdle the march's organizers had to tackle. Countless volunteer security personnel were deployed into the crowd to eye any potential trouble; many of these men were equipped with two-way portable radios and assigned poetic code names like Freedom, Equality, Justice, and Jobs (per the National Archives).

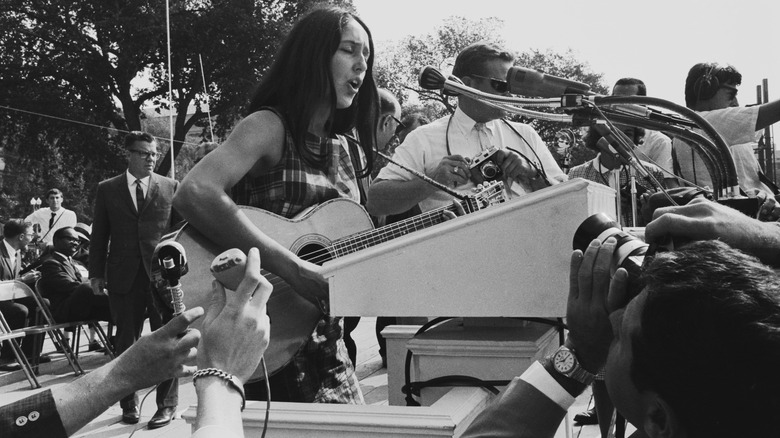

Singing and music engulfed the March on Washington

Multiple publications covering the March recounted singing as a recurring theme that August day. Speaking to NPR, Clayborne Carson, a professor at Stanford University who attended the March when he was 19, claimed that music was one of the crucial factors that helped carry the event and make it such a success.

Music was so prominent during the March on Washington that decades later, Jack Hansan, a white civil rights activist from Ohio, plainly told NPR that he remembered the songs more than the historic speeches. By all accounts, the march's atmosphere was jovial and absolutely engulfed with song. While Lyda Peters didn't remember hearing Martin Luther King Jr. speak, she did recall how, to her, it seemed like everyone was holding hands and singing (via USA Today).

Several heavy hitters from the music world attended and performed in D.C. that iconic day, including Mahalia Jackson, Marian Anderson, Joan Baez, Bob Dylan, Odetta, the Freedom Singers, and Peter, Paul and Mary. Baez, who performed "Sweet Freedom" and "We Shall Overcome," remarked years later, "I remember singing, and I remember that ocean of people. Never seen anything like it. I remember the electricity in the air" (via TIME).

The diversity surprised some in attendance

Before the March on Washington, Warren Hall, a Black National Guardsman who would be on duty that day, initially believed that only Black people would be marching that day; even his military superiors assumed the same (per D.C. Public Library). However, while the majority of demonstrators on August 28, 1963, were African-American, they were joined by countless other citizens from all walks of life. Indeed, this diversity was one of the first things mentioned in Walter Cronkite's coverage of the event.

The diversity of the crowds shocked even those in attendance. For a young Ericka Jenkins, who was 15 at the time, it was especially exciting to not only see so many Black and white people standing together but to see white Americans look extremely attentive toward the messages being conveyed that day in the capital (via "Nobody Turn Me Around"). The theme of togetherness permeated throughout the crowds. In a 2013 discussion with The New York Times, Janet Trinkaus, a white woman, recalled being moved to tears by Martin Luther King Jr.'s speech and being held and comforted by a Black woman.

Sixty years after the March on Washington, Rosemary McGill, who was 17 at the time, spoke with USA Today about her experience. "I sat back-to-back with a white girl on a grassy knoll and helped a blind (white) man up the steps of the Lincoln monument. I was just overwhelmed with such kindness and respect. Hatred left me that day."

Marchers had to get creative with their seating arrangements

Things quickly get cramped when over 200,000 people converge on a single area, and many of the people demonstrating on August 28, 1963, had to use their imagination regarding where to sit and stand. The Library of Congress published an iconic photo of an endless column of people seeking reprieve from the heat by sitting by the Reflecting Pool and dipping their feet. Demonstrators were constantly searching for shade, with many standing under trees, or even sitting in the trees themselves. Al Husen reported (via Smithsonian Magazine) that the entire grassy stretch between the Washington Monument and the Lincoln Memorial was filled with an ocean of onlookers and acknowledged some marchers climbed the trees close to the latter.

In August 2023, while speaking with USA Today, Clayola Brown, who was 15 then, remembered watching Martin Luther King speak while perched atop a tree. Brown was apparently so close to King that she thought he initially looked nervous. "I remember when he finally took that second breath — because it took him a couple — and he just started to speak. And he looked in the direction of the trees," she said. "We all felt like he was talking directly to us."

Marchers were joined by Hollywood A-listers

The March on Washington had a serious celebrity element to it. According to Marvin Levy (via Variety), the famous American publicist, a sea of stars unceremoniously flew into the capital and ignored typical celebrity travel procedure by leaving their entourage and representatives behind. Marlon Brando, Rita Moreno, Sidney Poitier, Paul Newman, Harry Belafonte, James Baldwin, and Sammy Davis Jr. were just some of the celebrity A-listers who attended the March on Washington.

Edward Flanagan, a then 20-year-old Howard University student, attended the March after completing a shift as a waiter and recalled standing so close to Joan Baez that he was able to notice she was barefoot (via CNN).

Robert Boyd, a New York City fireman who volunteered to help with security in D.C., remembered being surrounded by high-profile figures like Baldwin. Boyd was so in awe by all the star power nearby that he didn't even realize he was standing behind Martin Luther King Jr. "I was standing right behind Martin, but I was getting autographs from all the movie stars and writers because I recognized them and not him" (via The New York Times).

The march was a transformative experience for many in attendance

The March on Washington was a life-changing moment for many who attended. In 2013, John Hochheimer, a Jewish American who traveled to the capital alone as a 13-year-old boy, explained how the night bus to the capital and the march itself forever changed him. "As the son of Holocaust survivors, this night, [the march] radicalized me forever, as I could see no difference between the evils my family had experienced, and the evils of these people's" (via The New York Times).

For some young Black children attending with family, it was their first time learning about the terrible challenges their parents had to endure. Many were so transformed by the experience that it was a commanding call of destiny, prompting them to become full-time activists later in life.

For other African Americans, August 28 was a day of not only deep reflection but also regret. Joe Burden, a Black police officer assigned to the Lincoln Memorial steps where Martin Luther King delivered his historic speech, spoke with NPR in 2013 about how conflicted he was at the event. "When I saw those signs and placards and whatnot that the people were holding, then I realized, you know, they were speaking about me as well. You know, I had a job, but I needed the freedom as well ... When I think back, yes, I wish I could have marched."

Agitators were present and tried to disrupt the March on Washington

While countless Americans joined together to march and send a much-needed national message, there were those present who wished to disrupt the event. Janet Trinkaus described an eerie setting after arriving at the nation's capital, telling The New York Times in 2013 that she feared violence after hearing anti-march protestors shouting at those arriving to the capital.

George Lincoln Rockwell, the leader of the American Nazi Party, was in attendance and hoped to hold a counter-rally of sorts. The police deployed 200 men to keep him and his 70 supporters away from the marchers. Law enforcement arrested one American Nazi Party deputy leader who kept trying to make a speech. Rockwell and his men eventually left after few gathered to listen to him.

While most marchers experienced a jovial atmosphere filled with camaraderie, violence quickly followed them after they left D.C. There were many incidents reported of buses being pelted with rocks and getting hit by rifle shots after they departed the capital. On top of these criminal attacks, many demonstrators were refused service at restaurants and pitstops even before they left Maryland.

The March on Washington was a tremendous success. However, the awful treatment demonstrators faced on their way home immediately proved how badly change was needed. "Our people were returning from a tremendous affirmation of faith in democracy and received wonderful treatment in the nation's capital," Charles Evers, brother to Medgar Evers, said, "only to return to harassment, intimidation, and unjust treatment" (per "Nobody Turn Me Around").

Contemporary sources described the march as a 'gentle army'

The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom was an incredibly peaceful event. It was such a harmonious occasion that, a day after the event, The New York Times dubbed the ocean of demonstrators a "gentle army." However, this wasn't what local law enforcement and contemporary politicians anticipated. Even President John F. Kennedy and his administration feared violence could erupt; expecting riots, thousands of National Guard troops were deployed to help local police quell any outbreaks of violence. The selling of alcohol was even banned that day in D.C. (Though, the House of Representatives cafeteria still left beer on the menu that day.)

The idea that violence could possibly break out also made many marchers hesitant to attend. Ericka Jenkins' mother told her not to go, certain something bad was going to happen, Charles Euchner recounts in his book. Karen Rothmyer, a volunteer who had signed up to help one of the churches that day, discussed her trepidation about going to the March with The Nation in 2013. "[I] was uncertain about participating myself. One reason was the incessant talk of possible violence that had prompted federal officials to give employees the day off." However, as Rothmyer further elaborated, she saw nothing of the sort happen. Three arrests were made during the event — none were demonstrators supporting the March.

The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom was a rallying call for justice and equality. While the event's message was fiery, fervid, and vindicated, peace and harmony reigned the day as over 200,000 thousand Americans stood together in solidarity.