The Scariest Thing In It Follows Isn't The Shape-Shifting Monster

2014's It Follows is one of the best regarded horror films of the 2010s, with a 97 percent approval rating at Rotten Tomatoes and a critical consensus that calls it "smart, original, and above all terrifying." The film tells the story of Jay, a college student who, after a romantic encounter takes a surprisingly dark turn (not the kind you would expect), finds herself haunted by an unnamed being that can look like anyone, come from anywhere, appear at any time, and that absolutely cannot and will not be stopped until it kills her.

While the idea of an inexorably murderous force that can look like anyone and that is hunting you specifically is terrifying on its own, It Follows gained much of its critical acclaim from its thematic richness, and "wouldn't it be scary if a naked grandma killed you" is not a super deep take, unfortunately, despite how true it might be. Additionally, science has yet to discover a tireless, shape-shifting sex monster, so while that might be scary on a visceral, suspension-of-disbelief level, it's not a super rational fear. So what is it that It Follows is telling us, the viewer, is the real source of fear and anxiety? Read on, you might be surprised!

(Needless to say, this analysis of It Follows assumes you have seen the movie, so watch out for spoilers because just like the monster, they could pop up anywhere and everywhere.)

Shifting through horror history

Shapeshifters in horror fiction and cinema go back to the earliest days of the genre. That said, the majority of such stories feature a human who changes to a single particular animal or monster: Think about Dracula turning into a bat, Larry Talbot turning into the Wolfman, or Irena Dubrovna turning into a cat person in Cat People. (If you haven't seen Cat People, you should see Cat People.) Surprisingly, it's considerably less common to find a movie about a monster that can change itself into any shape to look like anyone or anything. They definitely exist, though, with probably the most notable example being the thing from the 1982 version of The Thing, which can assume the form of any living being it has killed and absorbed into itself, meaning the isolated researchers it is hunting never have any idea who they can trust.

Another notable example of a murderous shapeshifter is Pennywise from Stephen King's It, who despite being best known as a scary clown can actually appear as just about anything and usually twists the knife by changing itself into a child's worst fear before consuming them. And though not from a horror film per se, one of the most versatile shapeshifters is the T-1000 from Terminator 2, who can not only turn into other people, but even make itself look like part of the environment.

Such terrors work by feeding into paranoia and distrust as well as fear of the unknown, which is actually just a starting point for It Follows.

Sexual morality and sexual mortality

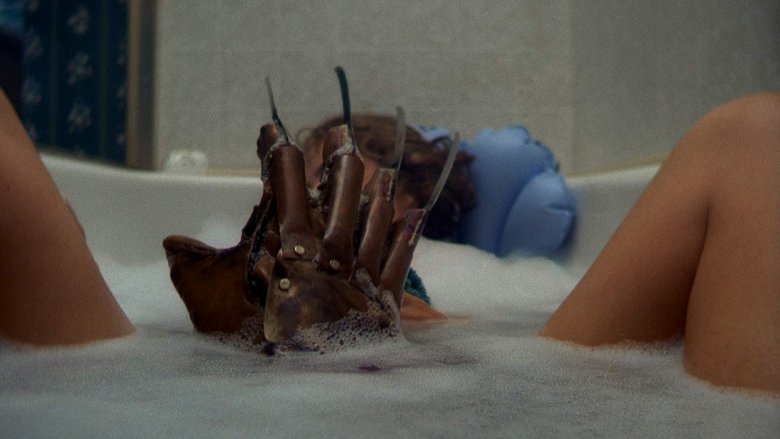

One aspect that makes the monster stand out from some of those other shape-shifting ghouls is the sexual angle of the film. Sex is how the monster is passed from victim to victim, sex is the only way to divert the monster's pursuit, and — based on the glimpse we get of Greg's death at the monster's, ahem, hands — terrifyingly violent sex is apparently the monster's preferred means of murder.

As laid out by Collider, sexuality and violence have a long and storied history together, particularly in horror cinema. But while the connection between the two ideas in horror can be traced back at least as far as Dracula seducing Lucy Weston in 1931 and while it might have reached new psychological heights with Norman Bates turning his shame at sexual arousal into crossdressing shower murder, perhaps the strongest connection between sex and death comes in the slasher subgenre. You can probably recite the tropes by heart: If you're a teen in a slasher, if you have sex or do drugs, your sleeping bag will be the next one smashed into a tree. The only one who will escape the phallic penetrations of the slasher's knife is the virginal Final Girl, who has rejected temptation and is thus transformed from prey to predator, and so on.

On the surface, It Follows seems to, well, follow this pattern. Jay has sex and a monster comes to kill her. But on the flip side, having sex diverts the monster as well. Clearly something more complicated is going on.

Scarier than chlamydia

The obvious — and very common — interpretation is that It Follows is a movie about a supernatural STD. And, honestly, if you had only read a summary of the movie's plot, that might track. Jay has sex with Hugh, a guy she doesn't know as well as she thinks, and after they're done, he tells her he's passed something deadly on to her and now she has to deal with it. However, the actual movie doesn't really support this interpretation, even from some of the earliest scenes. Compare, for example, 2013's Contracted if you want to see a movie that is definitely explicitly about STDs and note how different it is from It Follows. (Don't, in fact, see Contracted unless you really need to see a body horror film about STDs.)

It Follows is not a morality play in the sense of earlier slashers, as io9 explains. We learn that Jay has had sex prior to her encounter with Hugh, so this isn't some simplistic "loss of innocence and its horrific consequences" trope playing out here. As in real life, sex in It Follows has consequences both positive and negative. And honestly, one key sign that this movie isn't a metaphor for, say, gonorrhea is that STDs don't play by hot potato rules. You don't stop having the clap because you gave it to someone else. Something deeper and more universal (yes, even more universal than sex) is going on, and the earliest signs show up before the monster even shows itself.

"Where the hell would we go?"

At the very beginning of the fateful date that ends with Hugh passing the curse on to Jay, the two are standing in line for a movie and Jay explains a game she and her friends play in which they scan a crowd of people and say which one they would like to trade lives with. In the theater lobby, Hugh looks and picks a little boy whose dad is helping him drink out of a water fountain. When Jay expresses surprise, Hugh says, "How cool would it be to have your whole life ahead of you?" (Notably he does not say, "How cool would it be if it didn't burn when you pee?") He further expresses envy at the freedom children enjoy. When Jay notes he's only 21, he shrugs.

Later in the date, after Jay and Hugh have had sex but before he chloroforms her and tells her about the monster, Jay lounges in Hugh's car and gives a wistful monologue about her childhood fantasy in which she and some cute guy would just drive with no particular destination, "having some sort of freedom." But, she says, "now we're old enough, where the hell would we go?"

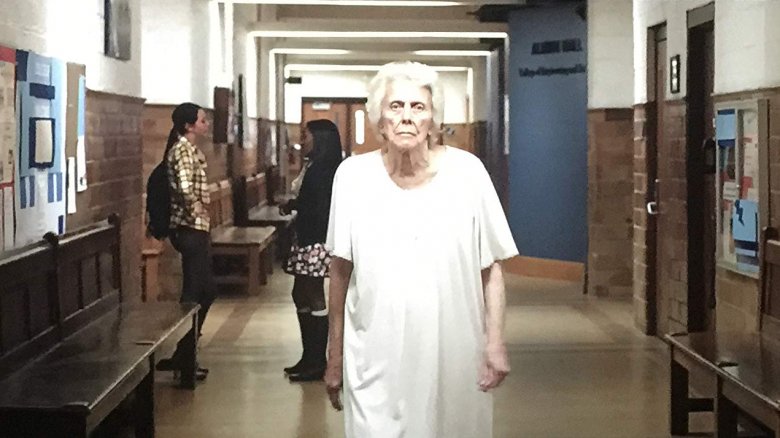

But wait, there's more: Jay's friends are shown on the porch playing cards, but it's no ordinary card game, it's Old Maid. When the monster first appears to Jay while she's in class, it's in the form of — wait for it — an old maid. The early evidence is there; now what does it all mean?

The lit's the thing

Here's a pro tip if you're watching a movie and struggling to pick out a theme: If there's a scene that takes place in a classroom, pay attention to what the teacher's saying. This pays off big dividends in Hereditary, and it also works great in It Follows. In the scene where Jay is at school and the monster first appears as the old woman, listen to the poem her professor is reading. Does it sound familiar? It might, because it's a poem very commonly read in high school and college English classes, "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock" by T.S. Eliot. This is a poem in which a middle-aged man expresses his fear of aging, inadequacy, decay, and death with such lines as "I have seen my head (grown slightly bald) brought in upon a platter."

The other work of literature prominently featured in the film is Fyodor Dostoevsky's The Idiot, quoted (in the second-to-last scene of the movie, to just really, really hammer it home) by Jay's friend Yara from her infamous clamshell e-reader: "And the most terrible agony may not be in the wounds themselves but in knowing for certain that within an hour — then within ten minutes, then within half a minute, and now — at this very instant — your soul will leave your body and that you will no longer be person — and that this is certain. The worst thing is that it is certain."

It's not a movie about monsters or sex: It's a movie about the awareness of one's own mortality that comes with the advent of adulthood.

Okay, it's a little bit about sex

Well, all right, to say that It Follows isn't about sex is disingenuous; sex and death are the movie's central concerns because it's a movie about young adults, and sex and death are the central concerns of young adults. The movie more than anything tries to replicate the emotional experience of being a young person on your own for the first time, so of course A) it's terrifying and B) it's about sex.

The reason sex is such a recurrent motif and more significantly why it's the trigger for (and the deferment of) the curse is that sex is such an important rite of passage, a milestone toward adulthood. The importance of sex as a marker of maturity is emphasized in the scene in which Jay and her friend Paul (who wants to be more than friends) reminisce about their first kisses and the time they found a box of porn in an alley. The emotional vulnerability that can come with full-on doing the do is for many people an eye-opening threshold: Welcome to adulthood, Jay! Hope you survive the experience! (Spoilers: You won't, none of us do.)

In an interview with the Guardian, writer-director David Robert Mitchell — though reticent to endorse any one interpretation of the film — explains why sex both attracts and diverts the curse: Jay "opens herself up to danger through sex," but "we're all here for a limited amount of time, and we can't escape our mortality, but love and sex are two ways in which we can — at least temporarily — push death away."

Detroit Rot City

The fear of aging and decay presents itself in It Follows partly through the forms the monster takes, whether it's the old woman standing out among a crowd of young bodies on a college campus, or the urinating woman in the house, or the naked old man on the roof, the latter two of which emphasize the connection between sex and decay. But another important visual signifier of ruin comes from the very setting of the film, namely suburban Detroit.

There aren't many explicit references to the geographical setting of the film, but as Slate points out, the architecture and references to 8 Mile Road make it unmistakable. The discussion about 8 Mile comes near the end of the film, when Jay and her friends are preparing for what they hope will be their final confrontation with the monster at the community pool. As they pass into the crumbling but strangely picturesque ruins of the city proper, they talk about how they weren't allowed to cross 8 Mile as kids. In this way, the city itself is a symbol for aging: The suburbs represent the pristine and safe childhoods in which parents hoped to keep death far away, while the decaying city proper is the wilds of adulthood, where your back hurts from taking a nap or sneezing too hard. And the line of demarcation between the two, 8 Mile Road, is ... sex? This analogy is gaining a life of its own here, but Eminem would probably agree, at least.

You're on your own, kids

Besides picking up the idea that the suburbs aren't enough to save your children from danger, It Follows pays homage to that other all-time horror great Halloween in one more key way: Where the hell are the adults? But while Carpenter was making a statement on the absenteeism of white parents who felt self-satisfied by their flight from the city, Mitchell seems to be saying something else with the scarcity of the older generation.

As Thought Catalog points out, you never see Jay's mom in full frame or in focus. She's off to the side, if you see her at all. Greg's mother is seen briefly talking about how messed up Jay's family is, and Hugh's (or Jeff's, as we learn his real name is) mom is there to answer the door, but that's pretty much it. This disconnect is an accurate reflection of the liminal age this movie is trying to represent: Hey, kid, you made it through high school, you're on your own.

Notably, the clearest view of any adults in this movie is when the monster assumes their forms. It looks like Greg's mom when it bones him to death, and it looks like Jay's (presumably dead) father in the climactic pool scene. The influence of the adult world is practically nil and the kids are left to fend for themselves, and when the adults do appear (so to speak), it's a violent intrusion that only serves to underscore the threat of mortality.

The persistence of memory

One of the key elements of It Follows that many viewers pick up on, even if only subconsciously, is that it is literally timeless. It is impossible to discern what year the movie takes place in. Thought Catalog makes a pretty thorough list of the various anachronisms, but some key examples are the old movies on the black and white CRT TVs, the mix of pristine-condition old model cars and brand new models, and the fact that none of the kids have cell phones but Yara has that clamshell e-reader that doesn't exist even in current technology.

Furthermore, it's impossible to place the season. The kids will be swimming in one scene and wearing heavy winter coats in the next. This is a deliberate choice, partially to create a subconscious disorienting effect, not entirely unlike the impossible architecture of The Shining.

But it's also because its message is timeless: It doesn't matter if it's the 1980s, the 2010s, or the 1910s when Eliot wrote "Prufrock," young people are always going to hit an age at which they recognize that death is coming for them and they can't stop it and — if they're lucky — their bodies will grow old and crumble to ruin first and ultimately they're on their own. Only they can see it coming, and it can come from anywhere or anyone. There's no way to stop it. You can only delay the despair of death with personal connections with others. And apologies to the T-1000, but that's scarier than any shapeshifter will ever be.

Conclusions and unanswered questions

There are a number of ambiguous scenes that leave the viewer with unanswered questions. Did the kids manage to kill the monster in the pool? Did Jay sleep with the guys on the boat? Did Paul sleep with the sex workers? Are Jay and Paul being followed by the monster in the final scene?

Part of the reason the ambiguity works in this movie's favor is that the answers to these questions largely don't matter. In an interview with Vulture, Mitchell addresses the kids' plan at the pool, calling it "the stupidest plan ever," one that "Scooby-Doo and the gang might think of," and of course it is. It's the Hail Mary play of a bunch of kids struggling to come to grips with existential terror in a way they can comprehend. Did Jay and Paul kill the abstract concept of death by shooting it in a YMCA pool? Well. Are they being stalked in the final frames? It doesn't matter, because they are even if they aren't. Death comes for everyone; welcome to the only game in town.

But what about the weaponized sex? Did Jay pass the curse on to the boat boys? Did Paul pass it on to the sex workers we see him cruising past near the end of the film? Again, the answer to these questions doesn't matter. It's enough that they considered killing someone else for their own safety. It shows that they've been irrevocably changed by the realization of their own mortality, miles away from the comfort of the suburbs and Scooby-Doo.