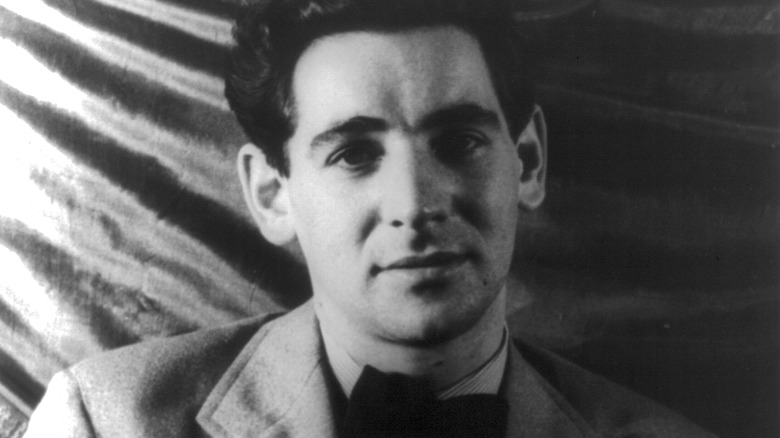

The Untold Truth Of Leonard Bernstein

Legendary composer and conductor Leonard Bernstein was no fan of critics, once telling The New York Times how fed up he was with them: "I suppose I am a problem for critics trying to be objective, I haven't opted for one school, or style, or cult," he explained. "I am very hard to pinpoint as either a performer or a composer. But they have to find a label for me, so a word like 'flamboyant' attaches itself ... I'm so sick of that word, I can't tell you."

So, what did Bernstein prefer? "Universal," he said, and also? "'Eclectic' is another one they pin on me, and it is a word I respect very much." And those are, of course, incredibly accurate. Bernstein enjoyed a decades-long career, both as a conductor and a composer, in a duality that greatly troubled him. His passion for music was unmistakable, and his skill was of the sort that could make any listener feel that same passion in their very bones. Still, he was a complex, often troubled individual who spoke to the masses through music ... so let's look at some of the things that have gone long unsaid.

There's no agreement on how his musical talents first appeared

Many great musicians show their talents young, such as Mozart, who famously started plinking away on the harpsichord when he was 3 years old. Leonard Bernstein's story is perhaps a little different, and according to Meryle Secrest's biography "Leonard Bernstein: A Life," the widely accepted story is that he didn't even touch a piano until he was about ten years old. His family was asked to store a piano for his aunt, he hit a few keys, was given lessons, and the rest is history ... so the story goes.

Secrest's research turned up some other stories, though, and concludes that no one is quite sure when Bernstein's phenomenal gift for music first manifested. Another version is that those lessons weren't so much demanded as they were encouraged, by a neighbor and music teacher who saw the young Bernstein playing an imaginary piano along to the music in his head. And yet another version of the story has Bernstein's first exposure to a piano coming much earlier, when he could hardly walk, and saw — and tried to play — the instrument at his neighbor's house.

If it seems strange that no one in the family can remember when Bernstein first started to take an interest in music, Secrest says that there's a pretty heartbreaking reason for that: "It is said that even if they had known their son was destined to be a musical prodigy, they would not have done anything about it."

His severe asthma always helped define his life

No parent should want to see their children struggle, but according to what Leonard Bernstein's mother, Jennie, revealed in Joan Peyser's book, "Bernstein: A Biography," she didn't just watch his struggle, she feared for his life. Diagnosed with asthma at a young age, she revealed, "When he was a sickly little boy and he'd turn blue from asthma, Sam and I were scared to death. Every time he had an attack, we thought he was going to die." She recalled long nights sitting up with him, hoping he would make it to morning.

Bernstein's asthma continued to plague him, and by the time World War II rolled around, it was still bad enough that it got him a medical exemption. He wrote about how it was both a relief and depressing: He hated the idea of war, but he was also disappointed about not being able to fight.

According to Humphrey Burton's "Leonard Bernstein," another opportunity for military duty arose at a most inconvenient time for Bernstein — he was serving as a guest conductor and had a job with the New York Philharmonic lined up when he was reclassified as eligible for active duty. Burton says that his mentor, Serge Koussevitzky, wrote a letter to the U.S. Army Medical Examiner to testify that he would be much more useful in music. The following month, Bernstein was once again classified as unfit for active service, which greatly upset him at the time.

The moment he realized the power of music

If someone's really fortunate, they'll have a moment in life that defines what they want to do for the rest of it. According to Meryle Secrest's "Leonard Bernstein: A Life," Leonard Bernstein had his moment in 1937, when he was spending the summer working as a counselor at Massachusetts's Camp Onota. He already knew that he loved music; he'd already taken lessons and found his talents, but he would later write that it was one day that season that he saw the power that music could truly have, as it drifted over a group.

Music, he'd write, was pretty standard fare at that time, and one of his jobs was to play the background music on the days when parents would visit. That summer was also when one of his idols died at a shockingly young age: George Gershwin passed away on July 11, while undergoing surgery to remove a malignant brain tumor, and Bernstein said when he heard, "I was absolutely devastated."

For that day's music, he first announced to the room that Gershwin had died, then started to play one of his works. The normal background chatter stopped, and he recalled, "That was the first inkling I ever had of the power of music, of its possibilities for control. It was a great turning point for me. Perhaps the most theatrical thing in the world is a room full of hushed people, and the more people ... are silent, the more dramatic it is."

From dreams of being a pianist to conductor

According to what his mother revealed in Joan Peyser's book, "Bernstein: A Biography," the initial goal was always to become a pianist. "That was my dream for him," she said, but as we all know, things don't always go according to plan. "When he met [Dimitri] Mitropoulos, all that changed."

Leonard Bernstein was a Harvard student at the time, and invited his mother — who he was always close to — to meet the conductor ... who was also a pianist and composer, along the same lines that Bernstein would eventually follow. And Mitropoulos knew not only his talent, but of his interest: He invited the young student to rehearsals, and later paid his way to Minneapolis while he was a guest conductor there. Although the job he had offered Bernstein didn't materialize as he'd hoped, he remained a major influence.

Bernstein would observe: "Watching him conduct ... laid some kind of conductorial passion and groundwork in my psyche which I wasn't even aware of until many years later. I remember every piece he did. All ... I do is proof enough of the force of that influence." Those who knew them say Bernstein also found inspiration in the fact that he was a gay man in a position of power: At the time, the idea that an entire orchestra would respect a gay man as an authority figure was nothing short of life-changing.

The story about being hired by the New York Philharmonic is unclear, but weird

Leonard Bernstein's connection with the New York Philharmonic is legendary, but here's the weird thing: According to Humphrey Burton's biography, "Leonard Bernstein," the story of how he was hired there has been so embellished that no one's really sure quite how things came together. Bernstein even claimed that the man who hired him, Artur Rodzinski, had a little divine guidance in the matter. Rodzinski, Bernstein would say, told him, "I am going to need an assistant conductor. I have gone through all the conductors I know of in my mind and I finally asked God whom I should take and God said, 'Take Bernstein.'"

Rodzinski reportedly shared the revelation with Bernstein when he spent a few days with the elder conductor at his farm, promising the then-25-year-old Bernstein that he would attend rehearsals, learn, and eventually conduct his own show that season. Hilariously, it was all offered before Rodzinski had even seen Bernstein conduct

While it seems unlikely Bernstein would have been hired as an assistant conductor with his talents untested, Rodzinski apparently had his share of eccentricities that make the leap of faith completely in character. In addition to his insistence on having a loaded gun in his pocket while he conducted, he was also the sort to give Bernstein some ... unconventional tasks. The strangest? "... to kick his boss on the backside with his knee for good luck as he went on to the platform."

He confessed his love for an Israeli soldier

When Leonard Bernstein visited Israel in 1948, things were dire: The War of Independence had kicked off in a big way, but he was incredibly moved by it. In a letter he sent from Tel Aviv, he wrote (via "Leonard Bernstein"), "I am simply overcome with this land and its people. I have never so gloried in an army, in simple farmers, in a concert public." He spent much of his time with an Israeli soldier who had been appointed his guide, and he wrote of their romance, too: "I can't quite believe that I should have found all the things I've wanted rolled into one," he wrote in a letter. "It's a hell of an experience — nerve-wracking and guts-tearing and wonderful. It's changed everything."

That soldier was Azaria Rapoport, and according to Jewish News, he was a big part of the reason that Bernstein had planned on extending his trip. In the end, though, he headed back to New York: The grueling schedule meant that he hadn't had time to sit and compose, and he turned down an invitation to become the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra's permanent conductor.

"That broke my heart," he told a journalist. "I wanted to do it. But I can't do everything. ... I can serve music and Israel much better by being careful now and doing the job when I'm ready for it." As for Rapoport, he visited the city in 1949, but the relationship apparently ended.

Several people wanted him to go by different names

Nowadays, almost everyone knows the name of Leonard Bernstein, but there were several times in his life when his name was actually sort of up in the air. According to Joan Peyser's "Bernstein: A Biography," Bernstein's maternal grandmother wanted him to be named after her brother, Louis ... and his parents actually did it. They, however, decided that for everyday use, they were going to stick to the names they preferred: Leonard and Lenny.

Bernstein grew up thinking that was his actual name, and it was only when he went to school and the teachers looked for "Louis Bernstein" that he realized his actual name, and the name he always thought he had, were two entirely different things.

He eventually changed his name to "Leonard," but it wasn't long before he was advised to change it again — this time, for a very different reason. When Bernstein started down the career path to conducting, he was advised to change his name to something not as easily identifiable as Jewish. The Religion News Service says that it was Serge Koussevitzky who told him that he'd be better off working under a different last name, reportedly suggesting he shorten it to "Burns." But Bernstein didn't relent: "I'll do it as 'Bernstein' or not at all."

His FBI file was ridiculously long

In the grand scheme of things, orchestral music might seem like the least controversial and most wholesome thing out there, but it turns out that Leonard Bernstein was shockingly controversial ... as far as the FBI was concerned, at least. In 1994, The New York Times took a look at his recently-released FBI file, and they had a lot to go through. Surveillance of him started in the 1940s and continued for more than 30 years, resulting in a whopping 666 pages of intel.

The documents indicated that questions about Bernstein's loyalties had long been of major concern, citing instances, including his support for anti-fascist and left-leaning organizations, that the government viewed as getting a little too close to communism for comfort. (They say that they never found anything concrete to actually tie Bernstein to communist beliefs, and he denied associations with the Communist Party while under oath.)

Not long after the release of the documents, Bernstein's daughter, Jamie, wrote a piece for a Bernstein-centric newsletter, Prelude, Fugue & Riffs. In it, she recalled her family being targeted by hate mail and protests, then later finding out "that those demonstrators teemed with FBI infiltrators." She claimed the FBI was also behind the hate mail campaign, and wrote: "For a time my father's stature as a musician was overshadowed by his awful new role as object of trendy ridicule ... But the FBI, despite all its efforts, never could crush my father."

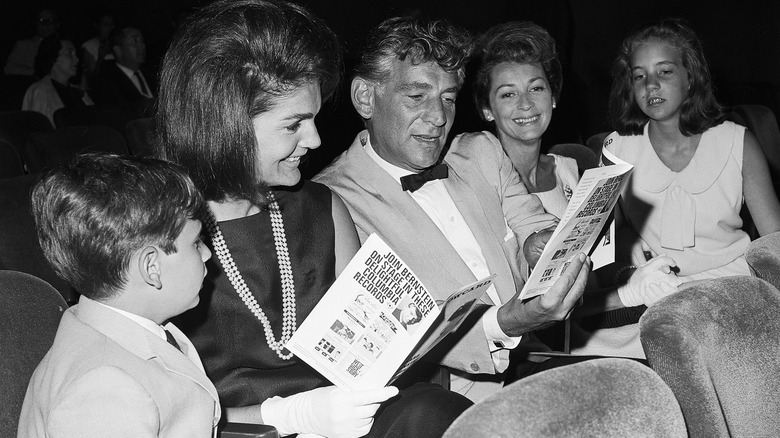

A fundraiser for the Black Panthers caused some serious chaos

Leonard Bernstein's daughter, Jamie, would eventually reveal that it had been her mother (pictured, with Bernstein) who organized the fundraiser, but it was her father who made headlines for it. Those headlines included a 1970 piece by The New York Times, which covered the event and proclaimed, "Black Panther Philosophy is Debated at the Bernsteins," and quoted him as wholeheartedly agreeing that violence was the only way to set the country right.

Was the FBI interested in that? Absolutely. The fundraiser was organized by the Bernsteins to raise money for the defense of the so-called "Panther 21," a group of Black Panther members who had been arrested and accused of conspiring to carry out a series of bombings and attacks. When word got out that many were jailed and held on impossible-to-afford bail amounts, many saw it as an affront to justice and a violation of civil liberties. (It's also worth noting that ultimately, all were acquitted of all charges.)

New York Magazine coined the term "radical chic" to describe what they thought was going on there, accusing Bernstein — and other wealthy elite — of basically taking on causes that allowed them to associate with radical extremists in a socially acceptable way. The Bernstein family's insistence that they only wanted to see justice done right was overshadowed, and Jamie would later write: "[her father] never abandoned his convictions."

His work with an orchestra of concentration camp survivors was controversial

In 1948, Leonard Bernstein headed to Germany to conduct an orchestra made up entirely of survivors of the Nazi's concentration camps. They met at a displaced persons camp, got together through the shared bond of their experiences and their love for music, and were ultimately recognized by the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (JDC).

They were asked to put on a series of performances in the aftermath of the war, and Bernstein was asked to conduct. Those who saw the concerts say it had a lasting impact on them: Bernstein addressed the people gathered to listen by speaking in Yiddish, and he was moved to tears by the greetings he received. For many, it was the moment they realized they really had survived. Music had returned, but at the same time, they cried for those who weren't around to hear it.

However, along with conducting the orchestra for the JDC, Bernstein also agreed to conduct performances of the Bavarian State Opera. In letters (via Time), he wrote that "It means so much ... since music is the German's last stand in their 'master-race' claim," and that he viewed the concerts as a major success. Behind the scenes, those in the know knew that it would be wildly controversial if it got out that he'd done a state concert along with working with the survivors, so it was all kept on the down-low.

He didn't like that iconic film version of West Side Story

Leonard Bernstein is synonymous with "West Side Story," but it turns out that he can also be put on a list of artists, writers, and musicians who didn't really like their most iconic work. According to what Bernstein's daughter, Jamie, told The London Times, "It became a sort of albatross around his neck. He had to work all the harder to get people to focus on his other works, especially his symphonic works. He did mention it from time to time, it was a frustration."

Her sympathy only went so far, apparently, as she did say: "But you can't really get to complain about having a gigantic success." And still, it seems Bernstein was at least a little protective of his musical, as he once turned down Disney's offer to make a version of it — at least, sort of. As "Lilo & Stitch" co-director, co-writer, and voice artist (of Stitch) Chris Sanders told Vulture, he actually didn't show up to the pitch meeting.

Sanders says he was flown out to New York: "Jeffrey Katzenberg ... wanted us to do 'West Side Story' with cats," he recalled. "I boarded this huge sequence where these cats were battling each other. ... Leonard Bernstein didn't show up for the meeting. He sent representatives. I'm sure they were people of some prominence; there was one woman in particular who had a lot of necklaces on. But you could tell it wasn't going well."

On the difficulties of composing an opera

When Leonard Bernstein premiered his "Songfest" with the New York Philharmonic in 1977, The New York Times talked to him about that acclaimed performance and his other works, too — and in one instance, a lack thereof. Bernstein acknowledged that one of the things he had never written was a full-length opera, and that's sort of surprising. He gave some insight into why that was.

"The reason is that I was convinced the true American opera would grow out of the Broadway musical," he said. "'West Side Story' is not an opera, though it has strong operatic elements, but I thought of it as a step in the direction of what the American opera would finally be. I expected others to take the next step, that's why I left Broadway and went to the Philharmonic."

Bernstein said that he was disappointed that his vision of an American operatic tradition never materialized, and said that he saw Broadway as going "backwards instead, to formulas and commerce." Not having written an opera doesn't mean that he didn't try, and he added that he made several attempts at writing his operatic masterpiece. Nothing ever panned out; the work just didn't come together, and he ended up walking away from the idea repeatedly (with only a few small pieces to show for his efforts).

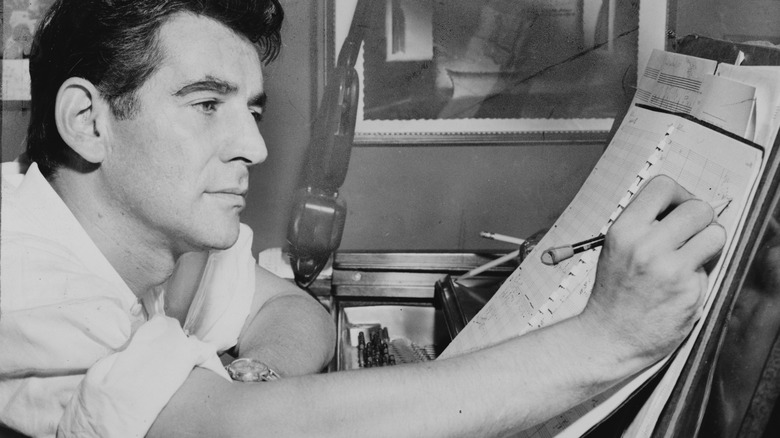

Conductor or composer? Here's what guided the conflict

The merits of Leonard Bernstein's career as a composer versus conductor could be debated endlessly, but Bernstein himself has weighed in on the debate. Barbara Haws, an archivist for the New York Philharmonic, says (via NPR) that the question of which to focus on was one of the biggest conflicts that haunted him throughout his career, and he even wrote of believing his fellow composers may have pushed him toward conducting so that he could both promote the work of others, and not compete with them.

But Bernstein's daughter, Jamie, says (via NPR) that there's more to it than that, and it was something that he always struggled with. Preserved in the book "The Leonard Bernstein Letters" are some thoughts that he wrote to a college roommate back in 1939: "You may remember my chief weakness — my love for people. I need them all the time — every moment," he wrote. "It's something that perhaps you cannot understand: but I cannot spend one day alone without becoming utterly depressed."

Jamie said that she had been both surprised and not surprised when she read the letter, and noted that for as long as she could remember, he'd craved constant company — which was one of the major reasons that he didn't compose as much as he may have liked. "That was the hardest thing for him about composing," she explained. "It was so lonely!"

He found the written word just as magical as music

There's a fascinating bit of trivia that's featured in Slate's examination of Stephen Sondheim and crosswords: They say that just as he had been introduced to word puzzles by mentor and lyricist Oscar Hammerstein II, it was Sondheim who passed on the passion for crossword puzzles to Leonard Bernstein while they were working on "West Side Story." He recalled always picking up a new puzzle on Thursday mornings: "I got Leonard Bernstein hooked," he said. "Thursday afternoons no work got done on 'West Side Story.' We were doing the puzzle."

In her book, "Famous Father Girl: A Memoir of Growing Up Bernstein," Bernstein's daughter, Jamie, talks about how one of their favorite games to play were word games — particularly, anagrams. They all enjoyed it so much that she said she had no interest in her father's work as a conductor: "We just wanted to stay home and be a family and play anagrams," she said (via NPR). She also shared one instance where anagrams became more than just a game, and says that Bernstein struggled his whole life with something he called the "elf's thread," which he created as an anagram of "self-hatred."

In a 1977 interview with The New York Times, Bernstein said, "I am so attracted to words; I love them as much as I do notes. ... The whole linguistic idea is a magical one to me, almost as magical as the phenomenon of music."

No hands necessary

Leonard Bernstein is known as an enthusiastic conductor, and it's just as fascinating to watch him as it is to listen to the music that he extracts from an orchestra. That's what makes one performance in particular equal parts weird and interesting. It's Bernstein conducting the Vienna Philharmonic through Haydn's Symphony No. 88., and at a glance, it seems like he's doing, well, not much of anything, aside from the occasional grimace or nod.

NPR pondered what, exactly, was going on, and shared that he's doing something that's sometimes called "eyebrows only" conducting. Alternately, it was an Israeli conductor named Itay Talgam who dubbed it, "doing without doing." Bernstein himself was quoted in order to give some idea as to the method behind it: "[Conducting] is not so much imposing his will on [the orchestra] like a dictator. It is more like projecting his feelings around them ... It doesn't really matter how well you move with your hands. It should be in your face, it should be in your expression."

In the particular performance featured above, he shows just what that technique looks like, and interestingly, there's another theory behind this: It's the idea that perhaps Bernstein was showing off. By backing off, by toning it down, he could demonstrate just how good he was.

1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, a 21st birthday, and the end of a marriage

Leonard Bernstein and his wife, Felicia, had a famously tumultuous marriage that was punctuated by his affairs with men. Humphrey Burton's biography, "Leonard Bernstein," provided some insight into that marriage, and he recounted the tale of the failure that was "1600 Pennsylvania Avenue." Friends and family remember that after it opened to dismal reviews, he blamed his wife for encouraging him to do the project in the first place, and berated her to tears.

It was so widely panned that it's been largely lost: Bernstein recycled some of the material, but it was so bad that it was never even recorded the few times it was performed. Burton says that the flop had a major impact on him, making him step back, take stock of his life, and try to figure out what he wanted. That led to him spending more and more time with Tom Cothran, and resentment — made worse by Felicia's discovery of love letters between her husband and his lovers — boiled over at their son's 21st birthday party.

That son, Alexander, remembered his father melting down into misplaced rage after finding him smoking with some friends instead of hanging out with the family, and in hindsight, realized that his parents were under the stress of an ultimatum. They would ultimately separate, but Bernstein would move back in with her after she was diagnosed with lung cancer, and care for her until her death.

His daughter has written about what it was like to grow up with her famous father

Jamie Bernstein's memoir, "Famous Father Girl: A Memoir of Growing Up Bernstein," provides an unprecedented look at the man behind the fame — and she certainly doesn't pull any punches. She writes (via NPR) that in addition to being a brilliant man who loved to play word games with his children, he could also be hard to associate with.

She's been candid, too, about the impact a famous father had on them, saying, "It's hard to live in a very bright sun and try to figure out what you're going to be on your own in that blinding light." She said that she had little choice but to give up her own attempts at music, and added that she was similar to her father in that she described them both as "obnoxious." She explained, "He was exuberant, ... he was a know-it-all and he had answers for everything, and liked talking at great length and was bossy."

A review in The Washington Post focused on other things, too, which — especially in the #MeToo era — read as troubling. She recalled what was described as a full-on French kiss that wasn't uncommon: "Daddy tried this tongue-kissing stunt on almost everyone," and touched on episodes like her father impaling his son's Harvard diploma on a kitchen knife during his graduation party, and some rather uncomfortable dance-floor shenanigans with his daughter, leaving it up to the reader to draw their own conclusions.

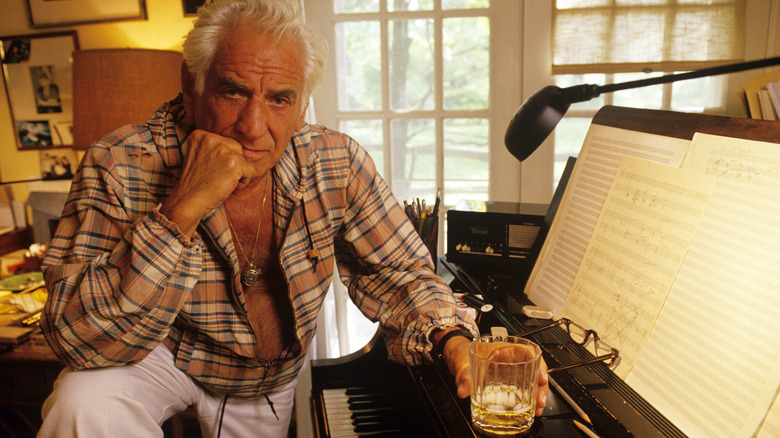

His final days were dire

Leonard Bernstein passed away in 1990, and according to his obituary, the official cause of his death was sudden cardiac arrest, which had been brought on by progressive lung failure. That all came after a diagnosis of lung infections, progressively worsening emphysema, and the development of a pleural tumor.

When The New Yorker looked at his life before and after the 1978 death of his wife, they wrote, "guilty and lost, he fell apart," and noted that even though every doctor he saw told him that he needed to stop smoking, he continued — even lighting up in their offices. By 1988, his unhealthy lifestyle had caught up with him, and his daughter, Jamie, wrote, "Everything had become such an effort for him: his breathing, his insomnia, and all the additional threescore-and-ten indignities."

When The New York Times reported on his death, they noted that he had only announced his official retirement earlier that same week. They also noted that fans had for years been asking him to stop smoking: They even took the memorial service for Alan Jay Lerner as an opportunity to carry signs addressed to Bernstein: "We love you — stop smoking." He was known for carrying a respirator to help him breathe and a lit cigarette at the same time, but it was fellow composer Bright Sheng who recounted his final hours: "He was lucid, even witty," he recalled of the visit. "I was happy for him at that moment."