The Accusers At The Center Of The Salem Witch Trials

The Salem Witch Trials is an American horror story that has been told in two ways. First, it was a story of real witchcraft, black magic, and demonic possession, which shook contemporary 17th-century society to its core. Within a few years, however — and with the benefit of much hindsight — it came to be interpreted as a terrifying tale of mass delusion, one which led to the loss of many innocent lives.

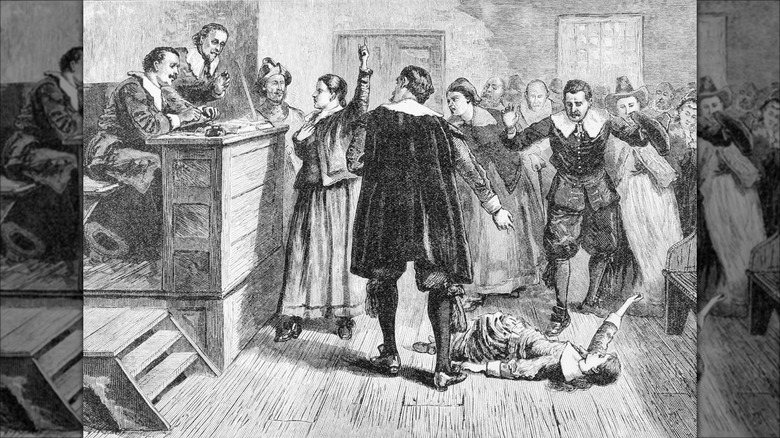

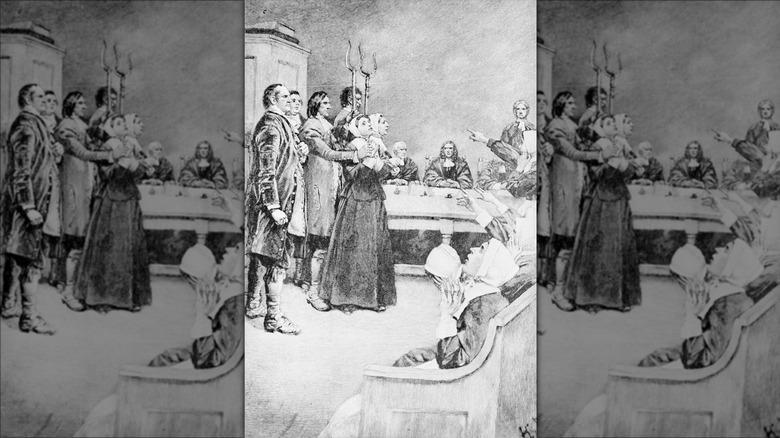

Beginning in 1692 in the town of Salem, Massachusetts, more than 200 people were accused of witchcraft, with scores arrested and taken to trial for the perceived offense. As reported by The New Yorker, the trials relied heavily on what was described by prosecutors as "spectral evidence" that the witches were communicating with the devil to "afflict" local people. Countless people were put on trial, after which 25 were executed for the crime of witchcraft. But as the mania died down in the years that followed, the Salem Witch Trials were reassessed as a terrible and tragic mistake, the result of misplaced religious fervor.

One of the central figures in the frenzy that led to the killings was Samuel Parris, the pastor of the local church. His position at the center of the community and proximity to some of the accusers meant that he facilitated much of the action against those who were accused and fanned the flames of suspicion toward them. However, the actual accusers — those who named names and claimed to have been "afflicted" by witchcraft — were other members of the local community.

Elizabeth Parris and Abigail Williams

While journalist Rebecca Beatrice Brooks' History of Massachusetts blog lists dozens of people from across the state who made accusations of witchcraft against individuals, the accusers at the center of the story were a small group of girls and young women. The first to emerge as apparent victims of witchcraft were Samuel Parris' daughter, Elizabeth, and Elizabeth's cousin, Abigail Williams. When the saga started, the two girls were just 9 and 11 years old, respectively. However, their testimony still became the catalyst for one of the most needlessly bloody and disturbing episodes in American history.

The story begins with Elizabeth and Abigail claiming to be suffering from a number of unexplainable physical symptoms and exhibiting strange behaviors, such as fits and compulsive barking. According to "The Salem Witch Trials" by Stuart A. Kallen, Samuel Parris originally attempted to treat the girls through spiritual means, specifically prayer and fasting. But he was soon convinced of something more sinister after a neighboring doctor named William Griggs claimed that "the evil hand is upon them."

It later emerged that the two girls had been playing a divination game involving dropping an egg into water, which could purportedly tell young girls the profession of their future husband. According to Kallen, some historians claim this game took place under the supervision of Tituba, a Native American woman who lived in Salem. Regardless, she was accused of bewitching the girls, as were two other local women: Sarah Good and Sarah Osborne. By the time the trials were concluded, Abigail Williams had appeared on multiple occasions and testified against eight of the 57 people she accused. Elizabeth Parris never appeared in court,

Ann Putnam Jr. and Elizabeth Hubbard

Fantastical stories and rumors can spread like wildfire among children — especially when they are reinforced by the adults in the room. Tragically for those whose lives were destroyed or lost as a result of the Salem Witch Trials, belief in witchcraft was common among the Puritan community of 17th century Massachusetts. Soon, other children apart from Elizabeth Parris and Abigail Williams were beginning to exhibit uncanny behavior that seemed to suggest witches really did walk among the upstanding people of Salem.

First was 12-year-old Ann Putnam Jr. and Elizabeth Hubbard, who at 17 was the oldest accuser so far. According to the Salem Witch Museum, Putnam Jr. and Hubbard had fallen ill and claimed to have seen visions of specters. Putnam Jr. then claimed that the specters in her visions were a group of locals by the names of Martha Corey, Elizabeth Proctor, and Dorothy Good — Sarah Good's daughter. Dorothy was just 4 years old at the time.

Ann Putnam Sr. and Mercy Lewis

While the apparent bewitchment of the afflicted girls largely ceased after the arrests of those who had been accused of witchcraft, Ann Putnam Jr. reported that she continued to be visited by the specter of an old woman in a chair. With the growing suspicion that the purported visitations were caused by local people engaging in witchcraft, the Putnam household seemingly became obsessed with identifying the witch who tormented the child. Eventually, they accused a 71-year-old woman named Rebecca Nurse, and Ann's 31-year-old mother and the family's teenage maid Mercy Lewis soon claimed to be afflicted by witchcraft, too. Abigail Williams joined the Putnams in pointing the finger at Nurse.

Their claims piled pressure upon Nurse, and within days of the women seeming to fall ill, the woman they accused of witchcraft was arrested and made to stand trial. She was found guilty and hanged.

Mary Walcott

Mary Walcott was 17 years old when witchcraft fever hit Salem Massachusetts, and she joined the other young girls in the town in claiming to be suffering from a supernatural affliction brought about by witchcraft. Walcott was raised by her aunt, Mary Sibley, and it was through the actions of Sibley that witchcraft paranoia became fully fledged.

In the wake of the purported afflictions affliction, Sibley approached Tituba and her husband, John Indian, who she believed could make a "witch cake" and perform a ceremony that would rid the town of evil magic. Of course, when Sibley's actions came to light, pastor Samuel Parris admonished her in front of her church congregation, claiming that even though she had tried to end the bewitching by using magic, she had been "instrumental" in bringing the devil to Salem (per "The Salem Witch Trials").

Sibley repented and was spared a trial, but her niece proved to be one of the most prolific accusers of the Salem Witch Trials saga — her testimony on the stand led to the execution of 16 local people.

Mary Warren

Another Salem woman to make accusations was Mary Warren, a 20-year-old who worked as a servant in the house of the accused witch Elizabeth Proctor and her husband John, who was also later accused of witchcraft. Warren claimed to suffer from an affliction similar to those of the younger girls and testified at the trial of Rebecca Nurse, ultimately leading to the elderly woman losing her life. However, in a cruel twist of fate, Warren herself would soon stand among the growing number of innocent people who were accused of using diabolical magic against their neighbors across Massachusetts.

Having recovered from her affliction, Warren pinned up a public notice asking her neighbors to pray and give thanks that her fits had stopped. However, according to "The Salem Witch Trials: A Day-by-day Chronicle of a Community Under Siege," when this note was read aloud in church to the people of Salem, Warren was questioned by the townsfolk, and she claimed that "the afflicted persons did but dissemble." The congregation reportedly believed she was suggesting that the girls had been lying about their afflictions, and in the paranoid atmosphere that permeated the community at the time, these sounded like the words of a witch. She was later put on trial where she confessed to practicing witchcraft, though she claimed she had been tricked into it by spirits in the Proctor house. On the stand, Warren accused countless other local people of being witches, eight of whom would later be executed while another was tortured to death. Warren herself was ultimately spared.

Tituba

One of the most compelling figures in the Salem Witch Trials saga is Tituba. The Native American woman is described in several sources as an enslaved woman who worked in the household of Samuel Parris and had close contact with the girls who were first afflicted, per Smithsonian Magazine. She was one of the first to have been accused of witchcraft alongside Sarah Good and Sarah Osborne, but her story differs from theirs in that where they both vehemently denied being in league with the devil — Tituba confessed to having engaged in witchcraft.

Tituba even gave a detailed description of Satan, who she said had threatened to kill her if she didn't harm the girls in her care. As such, she managed to paint herself as a victim, and her testimony painted a vivid picture of the devil's presence in Salem. As her testimony went on, Tituba concocted outlandish stories that described her flying around the area with other witches — and implicated Good and Osborne as her diabolical accomplices. Per Smithsonian Magazine, these were the only names she would give, though she claimed knowledge of a conspiracy involving nine people ... a figure that later ballooned to 500, fuelling scores of arrests across the state. According to "Tituba: The Reluctant Witch of Salem," she later admitted to fabricating the testimony, saying that "her Master did beat her and otherways abuse her, to make her confess and accuse ... her Sister-Witches."