What Monarchs Do After They Abdicate

Heavy is the head that wears the crown — so why not take that troublesome tiara off and chuck it to the next poor sap in line? It's a thought that must have occurred to many a monarch in their least certain moments. For some, those moments were serious or numerous enough that they went ahead and abdicated for real. It's easy to imagine that giving up the throne and all of its rules and responsibilities is a thrilling moment. As their power, responsibility, and possible legal woes are transferred to someone else, quitting queens, kings, emperors, tsars, and the like may feel quite a bit lighter — at least until they consider their next steps.

After all, it's not as if a ruler stops existing as a person once we start to tack "former" onto the front of their title. They still have to contend with mundane matters like how they're going to make their way in the world. It can be a pretty troublesome prospect for modern ex-rulers, and that's without the added pressures of war, civil unrest, and politically cutthroat Bolsheviks breathing down the back of one's neck. Some have managed the transition nicely, with minimal bloodshed and even fond farewells from an adoring public. Others have had to be shown the door with considerable force. Meanwhile, a very unlucky few have found that there are more final ends than abdication.

Most abdicating monarchs have to engage in ritual and bureaucracy

When Japan's emperor emeritus, Akihito, abdicated in favor of his son, Crown Prince Naruhito, he couldn't simply step away and give a friendly wave to the new emperor as he strolled out of the palace. Instead, he took part in a private ritual in April 2019 that marked the transition to the new emperor's Reiwa era. This included a Shinto ceremony attended by Naruhito, his wife Crown Princess Masako, and Prime Minister Shinzo Abe. There, Akihito informed the family's imperial ancestors of the abdication and later made a short speech wishing Japan and the new emperor a peaceful reign.

Earlier, the Japanese parliament had to pass a single-use law that legally allowed Akihito to abdicate, as the nation's laws don't mark out an obvious path for the peaceful transfer of power from one emperor to another. That's because it's a very rare occurrence. The last emperor to abdicate before Akihito was Emperor Kokaku in 1817, more than 200 years before Akihito did the same.

A similar legal issue would face the British Parliament if their monarch decided to abdicate, though members of Parliament have at least faced this situation in more recent memory with the abdication of Edward VIII in 1936. While no one can legally force a queen or king to rule over the United Kingdom, undertaking an abdication the proper way would require that they get permission in the form of an official Act of Abdication.

Some run off to the monastery

After a life that was likely spent preparing for and then enduring the intense focus of being a nation's ruler, a quiet stint in a monastery must sound pretty nice. Chandragupta Maurya, the semi-legendary founder of the Indian Maurya Dynasty in the fourth century B.C., is said to have abdicated and become a Jain monk. Some stories even maintain that he died after fasting, as part of a religious rite known as sallekhana.

Other former monarchs haven't taken it to quite that extreme. John II Casimir Vasas, a 17th-century king of Poland, was a bit of a dud as a ruler going by the failed wars and all the land lost to the kingdom's rivals on his watch. He apparently was just as unimpressed with the business of ruling, as the combined pressures of war, a rebellious government, and the death of his wife led to his abdication on September 16, 1668. Afterward, he became a monk and led the French abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés.

Maybe John II was taking some cues from Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, who abdicated over a century before him in 1556, likely because of both the pressures of war and his own declining health. Once Charles had vacated the throne, he made his way to the Spanish monastery of Yuste (though he still managed to assist family members who were still in power, even while ostensibly taking it easy in his monastic retreat).

Compliant ex-monarchs can have a comfortable retirement

While some monarchs might have to be pried off the throne, those who don't raise a fuss might enjoy the easy life. Take Japan's Emperor Akihito, who decided to step away from the Chrysanthemum Throne in 2019 and leave the (ceremonial) ruling to his son, Naruhito. The former emperor said he wanted to abdicate while he was still of sound mind and body and may have wanted to keep the figure of the emperor from becoming overly politicized by keeping a more vital person on the throne. In retirement, he is reported to take plenty of peaceful walks, has plenty of time to read, and has access to a biology lab on imperial grounds where he can continue his passion for studying fish taxonomy.

Likewise, modern popes can expect good treatment after abdicating. Yes, the pope technically rules over Vatican City, which is one of the last absolute monarchies on Earth. Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI, who stepped down on February 28, 2013, after a series of controversies centered on both his rule and the Catholic Church in general, went into retirement with a small staff including medical personnel. After a stint in the pope's summer residence, he went to the Mater Ecclesiae Monastery in Vatican City where he died on December 31, 2022. Before that, he took walks in the monastery's well-appointed gardens, listened to music, read, prayed, and occasionally issued apologies for the abuse scandals that came to light during his reign.

Napoleon went back for round two

While some monarchs want to get the heck away from ruling, others clearly covet power, even while the ink on their abdication is still drying. Amongst the most power-hungry of all world leaders sits Napoleon Bonaparte, the French emperor who abdicated not just once, but twice in his ill-fated quest for power. The first go-around started on April 11, 1814, when Napoleon abdicated after a disastrous attempted invasion of Russia left him weakened and allowed other European leaders to form an alliance against him. Faced with encroaching enemy forces and army officials who didn't want to engage in yet another bloody war, Napoleon was forced to abdicate and then go into exile on the Mediterranean island of Elba.

That didn't sit right with Napoleon, who made his way back to mainland France after a mere nine months on Elba. There, he gained enough support that he took the throne as emperor again. His second reign is popularly known as the Hundred Days, though technically it was 110 days from his return to Paris on March 20, 1815; his second, even more definitive routing at the Battle of Waterloo on June 18 the same year; and his second abdication on June 22, 1815. Louis XVIII then took over the throne, and Napoleon was sent off to the far more remote island of Saint Helena in the South Atlantic, where he remained until his death in 1821.

Things can get awkward with the family

Britain's Edward VIII became king on January 20, 1936, but it seemed that the weighty responsibility was pretty daunting. Private letters he sent in the 1920s reveal that he thought the British monarchy was a dying institution. Then, there was "that woman," as upper-crust society liked to call her: Wallis Simpson, the American socialite and divorcée. Edward claimed that he loved her so much that he couldn't bear the thought of not marrying her. Parliament and society couldn't bear the thought of a twice-divorced American becoming queen. Something had to break, and it was Edward's rule. His abdication was endorsed by Parliament on December 11, 1936.

Edward's younger brother, now George VI, made Edward the duke of Windsor, but Simpson never got royal highness rank. The snub seriously damaged relations between the couple and the rest of the Windsors. The duke and duchess proceeded to travel about Europe, making very awkward friendships with Nazis and eventually spending the end of World War II governing the Bahamas. It took until 1967 for them to join an official public ceremony with the other royals.

Perhaps worst of all was the fact that his own wife wasn't necessarily fond of him. Prior to marriage, she reportedly felt trapped by his intense affection and even is said to have called him a fool for abdicating. She also kept up with ex-husband Ernest Simpson and maintained a close relationship with Herman Rogers, after her marriage to Edward.

Former monarchs might try to recover from illness

Sometimes, it's not the wars or ongoing scandals that get a monarch to abdicate. For a few throughout history, the issue is their own rebellious bodies. Ancient Roman emperor Diocletian, who abdicated on May 1, 305, at about age 60, reportedly did so because he was sick. Some accounts even claim that it was a stroke in about A.D. 304 that made it clear to him that his ability to rule effectively was waning. His retirement plan was to live in the countryside in what's now Croatia, farming vegetables — made all the sweeter by the magnificent palace that he had built there. He is said to have enjoyed it so much that, when a political ally pushed for his return to politics, Diocletian demurred by saying that his beautifully growing cabbages were evidence of how committed he was to staying in retirement.

In the modern era, Pope Benedict XVI claimed that he was stepping away from the papacy in 2013 because he felt that his health simply wasn't up to leading the Catholic Church anymore. The various scandals that came to light during his papacy, including reports of abuse cover-ups in the church and Benedict's alignment with ultra-conservative members of the church, likely contributed to his decision to step down. He went on to live for nearly 10 more years before his death on New Year's Eve 2022.

Inconvenient ex-monarchs can face untimely deaths

The last tsar of Russia, Nicholas II, gave up his throne on March 15, 1917, after a series of military blunders pushed both civil and military leaders to more or less tell him it was time to resign. Unlike in many other monarchies, however, there was no one to take his place. Nicholas meant for his brother, Michael, to become the next ruler, but he wasn't interested in stepping into the quagmire and refused. For the first time in centuries, Russia was without a tsar — and it would stay that way.

The working government effectively imprisoned the former tsar and his wife and children, originally with the idea of sending them all to England where they might have received a warm enough reception from the royal family there. There were plenty of family connections there, including the fact that Nicholas and Britain's George V were first cousins. But the Romanovs were deemed too inconvenient by the politically ascendant Bolsheviks and were assassinated in Siberia the night of July 17, 1918.

Looking further back, Russia doesn't seem to be a friendly place for abdicating tsars. Catherine the Great's troublesome dunce of a husband, Peter III, was forced to abdicate by his wife's supporters on July 10, 1762. He was hustled off to an out-of-the-way village where he mysteriously died soon thereafter — perhaps, as some have argued, at the command of his now very powerful wife who would have found a still-living former tsar very annoying.

Some become real partiers

If some abdicating monarchs decide to high-tail it for a quiet life somewhere obscure, or even spend the rest of their lives in a prayer-filled monastery, then it stands that others may feel drawn towards the opposite end of the scale.

Farouk I of Egypt certainly didn't appear to be interested in keeping a low profile. After he took the throne in 1936, people seemed pretty fond of the young, lively monarch. But, as his reign moved forward, things took a turn. It wasn't just that Farouk really liked to party, meeting up with women who weren't his wife and lavishly spending the kingdom's money. There was also the matter of corruption in his regime, as well as military defeats and disappointments at the hands of Israel and Britain. In 1952, he was overthrown — the coup reportedly began while Farouk and his courtiers were enjoying Champagne and caviar — and forced to abdicate in favor of his infant son. Egypt did away with monarchy entirely just a year later.

Shortly after the abdication, Farouk and his family left Egypt. They first headed to the Italian island of Capri, and then on to Monaco. In 1954, his second wife, Narriman, divorced him and returned to Egypt, claiming that the former king was guilty of adultery and "mental cruelty" (via Alarabiya News). Farouk stayed in exile and died in 1965 in a Roman restaurant, collapsing while supposedly on a late-night date with a young woman many years his junior.

Abdicating monarchs could be fleeing the consequences of wars they started

Quite a few monarchs throughout history have been obliged to step aside because of war and unrest. But, while some have faced up to their mistakes, others turned tail and ran. If they timed it just right and found a friendly enough place to set down stakes, they were sometimes able to escape the consequences of problems they caused.

In the waning days of 1918, Germany's Kaiser Wilhelm II certainly had a lot to run from. He had championed the expansion of Germany, in both a colonial and militaristic sense. He also apparently saw Germany's enemies everywhere, to the point where he began to isolate his nation. His backing of Austria-Hungary helped contribute to World War I and his poor management of his government and its alliances made the situation all the worse.

When other leaders determined that his blustery presence was in the way of wrapping up the violent conflict, he was pushed to abdicate. Kaiser Wilhelm followed through on November 9, 1918, then went on his way to Holland. He died there in 1941 at the height of World War II, yet another worldwide conflict that historians believe was caused at least in part by the global consequences of the First World War.

They might enjoy some handy legal protections

While modern monarchs are less likely to abdicate in the face of war — perhaps because there are so few left — they aren't free from controversy. Yet when prosecution becomes a topic of conversation, a former monarch's opponents may encounter some seriously tricky legal issues. Some royals, like Britain's King Charles III, are protected by the principle of sovereign immunity, which essentially states that they can't be prosecuted while on the throne (in the United States, sovereign immunity is a somewhat similar concept that says a state, federal, or tribal government can't be sued without its consent).

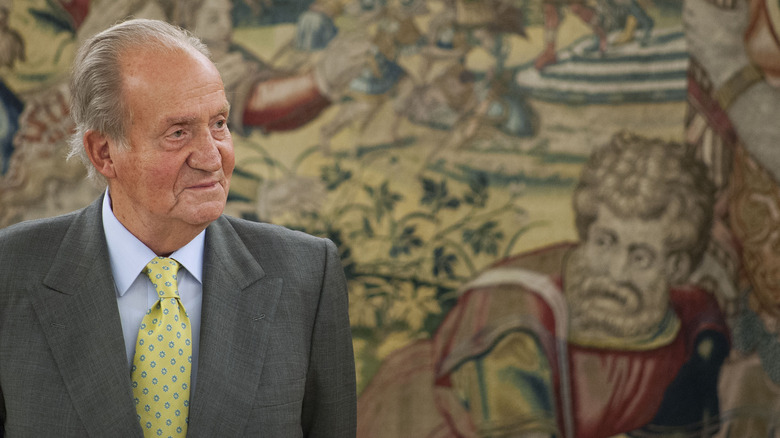

While Charles has so far followed the example of his mother, Elizabeth II, and steered clear of obvious legal impropriety, not all royals are so careful. Spain's Juan Carlos, who abdicated in 2014, did so in part because of rising questions about his profligate spending in the midst of a recession and staggering unemployment rates. However, he legally can't be prosecuted for anything he did while king. The catch: He can face consequences for anything he's done post-abdication.

The situation is murky enough that Juan Carlos has paid Spain more than $4 million euros ($4.8 million) in back taxes, perhaps in an attempt to keep real scrutiny off the rest of his finances. He also high-tailed it for a friend's residence in Abu Dhabi in August 2020. He didn't return until 2022, when, coincidentally or otherwise, investigators in Spain and Switzerland had given up investigating him for fraud.