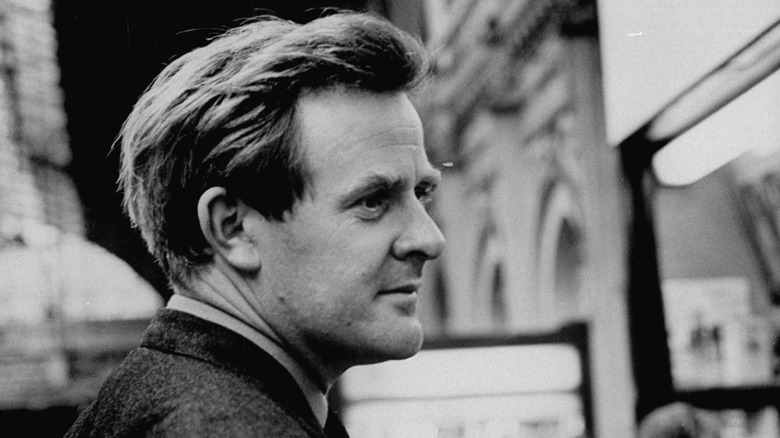

Why John Le Carré Left MI6 And Became A World-Renowned Writer

Meticulous crafter of gritty spy stories, John le Carré successfully drew on experiences from his career in espionage to create his grippingly realistic tales. But why did le Carré leave the British Secret Intelligence Service known as MI6 and retire to his writing desk?

For a time, le Carré was both a writer and spy — his nom de plume was adopted upon request by his boss so that his real name — David Cornwell — would remain a secret. His day job provided him with a lot of material, and he would cleave to the spy genre for the rest of his life. Although le Carré did have some qualms about life in the service — he once told NPR that the constant lying required to be a spy made him uncomfortable — he did not leave voluntarily but was forced out during the biggest scandal that we know of to hit British intelligence.

Le Carré along with many others was the victim of Kim Philby, one of the "Cambridge Five," who humiliated the upper echelons of British intelligence by spying for the KGB for many years without detection. The writer's willingness to expose the inner workings of the service didn't help matters either — and eventually led to calls for him to leave.

Philby and the Five

The man who ended John Le Carré's intelligence career was double agent Kim Philby. Philby was equipped with the stereotypical background of an MI6 agent — upper class, the son of a diplomat, and educated at Cambridge. In fact, Philby once told a group of Stasi agents that he had gotten away with his treachery because of his posh upbringing.

Although Philby looked like the sort of man bound to serve Queen and Country, in reality, he had become interested in communism as a student in the 1930s. He and the other members of the Cambridge Five spy ring — Donald Maclean, Guy Burgess, Anthony Blunt, and John Cairncross — were only gradually revealed to be double agents after years of successful espionage. Philby himself was only busted in the 1960s when he quietly got on a ship to the USSR and never returned. Today you can actually watch old footage of Philby briefing Stasi agents on the BBC website.

Later in life, Le Carré would describe Philby with absolute loathing calling him "a nasty little establishment traitor with a revolting father, a fake stammer and an anguished sexuality who spent his life getting his own back on the England that made him" (via The Atlantic). During the early days of his career, however, Philby was so well regarded he rose to the very top of the service.

Le Carré leaves the service

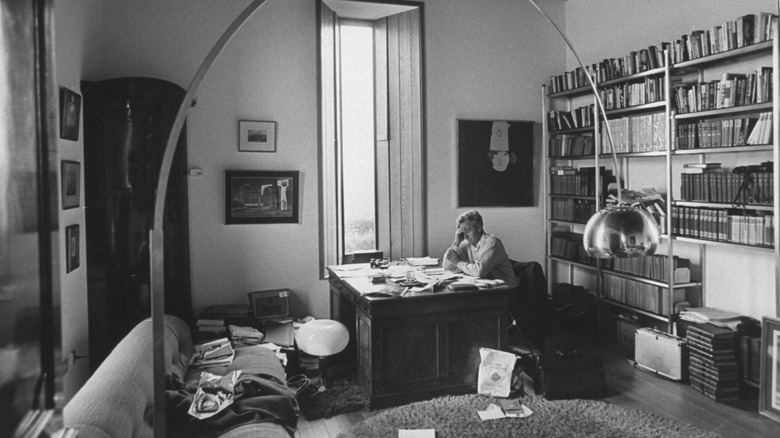

As a young man, Le Carré went to Bern Switzerland to study German in the late 40s. While there he was recruited as an intelligence officer and he worked in both Graz, Austria, and Bonn, Germany, during his career. By the 1960s however, Le Carré's writing career began to take off with the success of "The Spy Who Came in From the Cold."

The writer's depiction of the service as a dark world run on questionable ethics, along with his willingness to put himself out in the open as a writer, annoyed some within the service and supposedly left some insiders frothing at the mouth. His detractors were not wrong to get mad at him either — according to Brunel University, the realism of the novel raised some eyebrows abroad, and by 1965, one Soviet reviewer had already fingered Le Carré as a spy.

The final straw came with Kim Philby's disappearance in 1963, when it was discovered that Philby had blown the cover of many British spies working in Europe. Le Carré, who was considered a bit of a risk already, was asked to leave the service in 1964, shortly after the scandal. On the plus side, the debacle provided Le Carré with additional material for his books, and one of his best-loved novels — "Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy" — centers on the tense hunt for a mole in the service. Among the author's many admirers was Philby himself. In a letter to his wife, the infamous mole wrote that he admired "The Spy Who Came in From the Cold," although he believed the plot was implausible.