Here's What The Earth Is Really Made Of

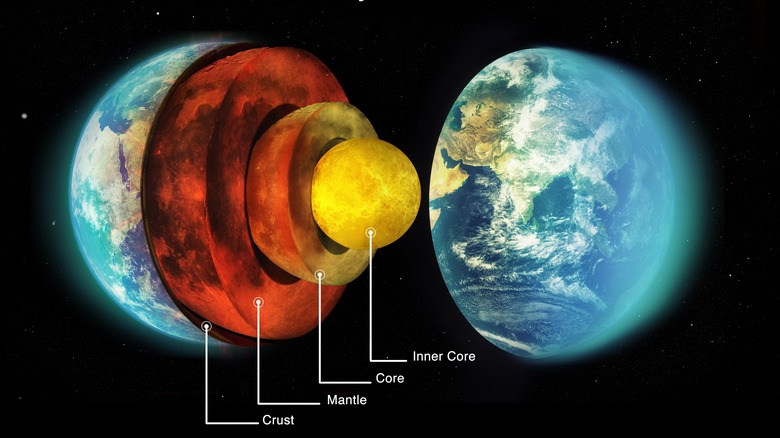

For most of human history, the center of the Earth was a huge mystery, and today startling new discoveries continue to re-write known science — giving us a more detailed picture than ever before. Earth's crust, is thought to be anywhere between three and 40 miles thick, depending on where you are standing (via Discover). Although it may contain mountains and oceans, the crust forms just 1% of the Earth's total thickness, made up of everything that didn't sink when the Earth began to cool. Under that is the mantle, which to date, man has never yet been able to reach, despite some valiant attempts to drill down into the center of the Earth.

Given we cannot just peer inside, scientists rely on seismology to get some idea of the makeup of the Earth's interior. The earthquakes that shake the ground beneath us every day can provide a picture of what's going on beneath our feet. Danish Siesmologist Inge Lehmann was the first person to suggest the Earth had a solid core and a more fluid mantle based on these readings — and she was only proved right in 1970 thanks to a marked improvement in technology. Details about the mantle and the core are still coming to light today.

The mantle and its mystery blobs

The Earth's Mantle extends to a depth of 1,802 miles and makes up most of the planet's mass (via National Geographic). Split into the upper and lower mantle, this part of the Earth is mostly composed of very hot silicate rocks, as well as a bunch of other stuff, including plenty of magnesium oxide, iron, aluminum, sodium, calcium, and potassium.

At the points where Earth's 15 tectonic plates meet in the upper mantle (the lithosphere), piping hot magma leaks up from the hotter asthenosphere beneath it, spewing out as lava from volcanoes. Underneath that is the denser and hotter transition zone, followed by the lower mantle a very dense area we know little about.

Many things about the mantle remain pretty mysterious today. Scientists do not know, for example, how viscous the mantle is or how fast it moves. The composition of the mantle is also not uniform; two superstructures known as LLSVPs (large low shear velocity provinces), or "the blobs," sit within it, located under the Pacific Ocean and Africa including part of the Atlantic Ocean. The blobs sit close to the Earth's solid iron core, and nobody knows quite what they are made of or how dense they are. They may contain unusual rocks or lava plumes, but either way, they seem to connect to some of the world's biggest volcano hotspots.

The core and its magma blanket

Beneath the mantle, is Earth's superdense core, the huge ball of iron and nickel that gives Earth its magnetic field. Scientists can't say for sure how hot the core is, but according to National Geographic, it ranges from a mega-hot 7,952 to 10,800 degrees Fahrenheit. The surface of this ball is composed of molten metal; however, its center is solid, made up of hexagonal-shaped iron crystals. As the Earth's interior continues to cool down, the inner core grows. As with the Mantle, there is still a lot of investigating to be done at this deepest part of the Earth, and recent research has changed our understanding of what's actually there. It is now believed that the core itself is surrounded by an area of molten magma.

Scientists first suspected that this molten layer was there after studying seismic waves, which appear to slow down dramatically when they reach the area above the core. According to National Geographic, it is thought that this incredibly deep pocket of molten rock might even be feeding some of Earth's volcanic hot spots.

That the core is surrounded by a sweltering magma blanket seems to have been confirmed back in 2010, when researcher Guillaume Fiquet crushed a mantle-like mix of iron, magnesium oxide, and silicon between two diamond anvil cells at the microscopic level. The hope was to simulate conditions similar to those in the Earth's crushing center. Fiquet's mixture successfully melted after reaching a heat of 4,200 Kelvin (7,100 degrees F) due to the extreme pressure.