What It Was Really Like To Captain A Ship During The Age Of Sail

Going by children's books and certain nautical movies, like at sea during the Age of Sail seems pretty glamorous, or at least pretty adventurous. And who would be at the center of all that adventure but a brave and highly capable captain? In quite a few tales of seafaring adventure, captains figure pretty prominently, whether they're barking orders at the height of battle, outmaneuvering pirates, or commanding a pirate ship themselves. And what kid wants to imagine that they're swabbing the deck or peeling potatoes in the galley, anyway?

But the reality of being a captain during this era could get far more complicated than the likes of "Treasure Island" and "Pirates of the Caribbean" would have you believe. The Age of Sail — generally accepted to span from the late 16th century to the mid-19th century — saw some captains who were hailed as heroes. It also saw captains who were lonely, abusive, killed far from home, and turned into the villains of infamous mutinies. Even the lucky ones would have had to deal with both the hardships of life at sea and the mind-numbing bureaucracy of navies and merchant businesses. Here's the reality of being an old-time sailing captain.

Early sailing captains had nebulous identities

Though the term seems painfully obvious now, the word captain was once applied to seemingly anyone of significant standing on a sailing vessel or even the commander of a group of landbound soldiers, whether they were on the waves or otherwise. It wasn't until 1555 that the word began to refer to one person in charge of a ship. It took even longer for this usage to become widespread.

When it comes to reputation, things are even more difficult to parse. If you go by legends of British naval officers such as Horatio Nelson, you'd think they were superheroes. Nelson rocketed to captaincy in 1779 at just 20 years old and became well-known for his valor, skill, and practically mythic death at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805.

Even earlier, tales of heroic and adventuring sea captains of the 17th century were part of the growing national story of England (not to mention its growing ambitions to become a globe-spanning empire). Certainly, that was the narrative that got picked up and turned into a national legend by the Victorian era, but the reality of being a sea captain during the Age of Sail could be far less glamorous. Besides the hard work of commanding a ship of sometimes hostile sailors, captains could also find themselves socially isolated and in dangerous situations — Nelson still died a painful, lingering death from a gunshot wound while at sea, even if the tales of his end later became glorified.

Becoming a captain could depend on social connections

Becoming a captain in the Age of Sail involved serious effort. Hopefuls in the Royal Navy had to serve for a minimum of six years before they were eligible to become lieutenants. It would be even more time before they could become a post-captain with a ship of their own. Having connections made this process easier and faster, such as when the preteen Horatio Nelson got his start serving on an uncle's ship, and then became an entry-level post-captain at the tender age of 20.

It wasn't all connections. For instance, captains in the 18th century Royal Navy got to where they were based on merit and had to pass a series of exams (promotions beyond that rank to admiral were typically based on seniority). Yet, even then, a captain was able to select his own crew and, in such situations, it paid to have some sort of personal connection that helped one rise out of the rabble and into the inner circle of officers aboard ship. With the right relationships, opportunities to prove oneself, and patience, even a humble nobody might make it as a ship's captain. And, as professors Guo Xu and Hans-Joachim Both argue in CEPR, this system, riddled as it might have been with blatant nepotism, also allowed savvy, clear-thinking officers to gather the best around them, promote highly qualified candidates to captain, and may have helped propel Britain to naval glory during the Age of Sail.

There could be a lot of bureaucracy

Ah, the life of a sea captain: the beauty of the ocean, the thrill of adventure, the pride of command, the ... joy of bookkeeping? Hope you like team meetings, too. That's because many navies were actually massive bureaucracies. Captains on privately held ships might have been able to loosen up a bit, but few navies would brook such nonsense.

As a result, captains in military contexts had to undertake plenty of unglamorous work. U.S. Navy captains during the War of 1812 had to ensure that their ships and crews were set up to face battle. This meant that they had to make a careful accounting of their supplies, recruit the right sailors, and then oversee the training that was vital to surviving a naval battle. He also had to make all the decisions, which could include both thrilling work during an engagement with British ships, day-to-day discipline, and nitty-gritty details about how to sail the ship.

The everyday life of such captains could also be filled with meetings and reports from various officers, informing him of the shape of his ship, the health of the men, the state of the stores, and other details that might make an adventure-minded person yawn. Yet, as much as nitpicking logbooks and surgeon's reports might feel like a paper-pushing nightmare, it was vital to make sure as many people survived as possible when battle loomed or the crew was in the middle of the ocean.

There were some perks, but not too many

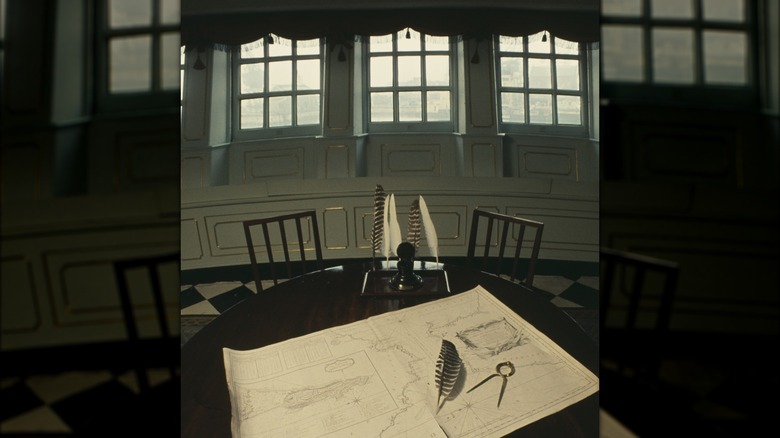

As the commander of a ship, a sailing captain would rightfully expect to enjoy certain privileges. Eighteenth-century sailor Samuel Kelly wrote that he sometimes experienced rather pitiful circumstances in which his sleeping area was dirty, neglected, or simply an out-of-the-way corner. Even better-ranking sailors would still have slept in hammocks strung across parts of the deck or in cramped quarters below. A captain, meanwhile, would have had his own private quarters, typically located at the stern (the rear of the vessel). Captains might also have a personal servant, known as a steward.

On some ships, like Nelson's H.M.S. Victory, captain's cabins could be seriously fancy, with multiple rooms and plenty of natural light. But other captains would have to manage with much smaller accommodations, depending on the size and purpose of the ship. Moreover, those rooms weren't just for lounging around but were often used for planning meetings and could even be broken down to act as an extra gun deck during battle.

At least captains could expect a better payout than everyone else. In the U.S. Navy during the War of 1812, captains got the highest pay of anyone on board ship, raking in $100 every month and chowing down on eight rations every day. By comparison, a lieutenant ranked just below captain received $40 per month and three daily rations, while an ordinary seaman who'd been on a couple of voyages would get $10 a month and a standard ration.

Captains were expected to discipline the crew

Maintaining discipline aboard the ship fell to the captain above all others. This didn't just mean screaming at the sailors, however. A captain — a good one, anyway — would have been looking to maintain order and hierarchy on his ship. This was especially vital in an era without the sort of medical knowledge or communications technology we have today. If things went wrong, everyone on board could be in mortal danger, far from help. This did mean that some punishment occurred, as you couldn't simply let a sailor who fell asleep on duty or who had begun to mutter about rebellion go free.

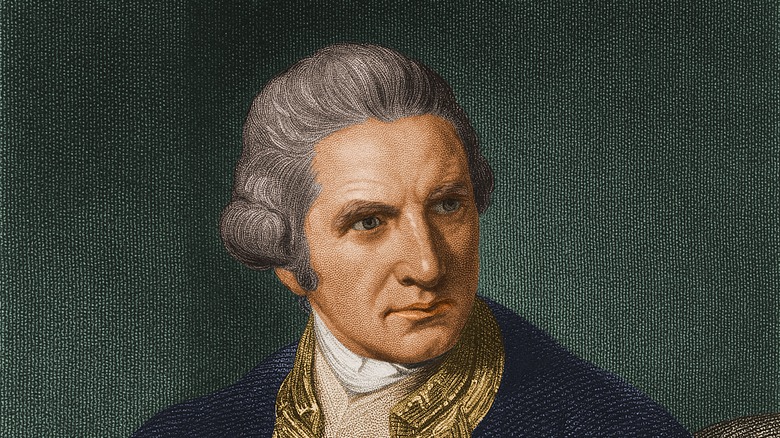

For many captains, enacting punishment turned them into a sort of theater director, as they meant to make a dramatic example of an offending sailor. They would call everyone on deck to line up and witness a punishment, which might include flogging or, in the worst cases, a hanging. Of course, a captain wouldn't usually want to go too far, given that sailors were a valuable and non-renewable resource, at least as long as the ship was at sea. He might even enact discipline in an almost motherly way, like when the 18th-century Captain James Cook used discipline to get his sailors to consume their rations. Food and drink were notoriously subpar on many voyages, but Cook was so wary of the effects of scurvy that he used his disciplinary power as captain to make sailors finish their meals anyway.

A captain's life could get lonely

Being captain of a sailing ship could bring extra rations, higher pay, and a shot at achieving glory, but it was often lonely at the top of the hierarchy. You couldn't reasonably expect a captain to fraternize with common sailors, as that could have undermined his dignity and authority. This left him to the company of other officers, which might have sufficed under the right conditions. Other figures might have been social companions, as was long the narrative for Charles Darwin's presence aboard the H.M.S. Beagle during the 1831-1836 voyage that took him to the Galapagos Islands. That story is a bit overstated, as Darwin was rightfully considered the ship's naturalist (and was appointed as such by the Admiralty). However, he also had the unique right to dine with Captain Robert FitzRoy and likely nerded out with him and other officers over their natural history collections, pointing to a clear social role that simply wasn't going to be filled by the rabble sleeping in hammocks below.

Lawyer and politician Richard Henry Dana also made note of this social quandary in his popular memoir published in 1840, "Two Years Before the Mast." While aboard a merchant vessel, he noted that a captain was in charge of everything to the point where he was the supreme law aboard ship. However, this state of affairs often left him with "no companion but his own dignity, and few pleasures [...] beyond the consciousness of possessing supreme power."

Captains sometimes brought their families along

In the Age of Sail, trips could go on ... and on, and on. Depending on the voyage and ship, sailors and officers would often expect to be gone for years at a time. For instance, a trip across the Atlantic between England and the United States could take somewhere between 25 to 30 days, though much depended on the vessel, what it carried, and the weather. Family members would often be left behind on shore while all of this went on. Yet, for some captains, there was the option of bringing a few family members along, particularly wives and children.

Some wives reportedly came on board with a bit of subterfuge, as when Rose de Freycinet dressed as a man to accompany her captain husband on a scientific mission in 1817. Her true identity was discovered in short order, but she was allowed to continue on the globe-circling voyage and write it all down in her journal.

Eventually, it became more acceptable to openly bring a woman into the still rather rough and tumble world of the sailing ship. Both navy and merchant captains sometimes brought wives on long voyages, though women were often expected to keep themselves shut away when activities like processing a dead whale were going on. It was widely considered to be a privilege of captainship, but one that left wives isolated, caring for young children in cramped quarters, and the objects of resentment for the rest of the crew.

Some navy captains could be exceedingly harsh

Onboard, a captain's command was law and there often was no appeal process for disgruntled sailors. During the Age of Sail, there was often good reason for such stringent measures, as help could be very, very far away if a crew found themselves in trouble. Enforcing rules and hierarchy could keep things running efficiently and safely, and such responsibility was laid at the feet of the captain.

Even so, some captains became notorious for taking this job too far. The Royal Navy eventually grew to have a pretty nasty reputation in some quarters for presenting sailors with harsh working conditions and harsher punishments, both of which could be made all the worse by an especially difficult captain commanding the ship.

Even captains once lauded as heroes have reputations with more tarnish than you might expect, once you start to look closer. The 18th-century British captain James Cook, once feted as a brave explorer, is now perhaps more accurately remembered as a colonizer whose sometimes rotten temper was not only taken out on his crew over long voyages, but was increasingly turned towards indigenous people of the Pacific islands who weren't keen on taking up European ways. Cook's growing tendency to capture and punish indigenous leaders like he did his sailors almost certainly contributed to his violent killing by Hawaiian locals at Kealakekua Bay on February 14, 1779.

Things could get treacherous

Power can be a tricky thing. Too much leniency and the crew goes wild. Too much control ... and the crew goes wild. Being a truly good captain meant walking a very taut tightrope between maintaining control of one's crew and allowing them enough freedom to avoid mutiny. While most captains seem to have done decently well at this, a few dealt with dramatic rebellions that could be linked back to their issues with leadership. Take the story of Captain William Bligh, whose command of the H.M.S. Bounty in 1789 threw his legacy into question for centuries. Things were looking good early on in his career when Bligh served as sailing master for Captain James Cook. Yes, he was on the voyage that saw Cook's death in 1779, but the Admiralty was still impressed enough by his work that he was given command of the Bounty in 1787 (though he was technically still a lieutenant). The crew was tasked with collecting Pacific breadfruit trees to transplant to British territories as cheap food.

But Bligh was only the lowly commander of a cutter who had to deal with a dip in pay, subpar officers, and agonizing delays. Bligh reportedly became so frustrated he took it out on the crew, including first mate Fletcher Christian, who orchestrated a mutiny on April 28, 1789. Set out to sea in a small boat with his loyalists, Bligh managed to survive, but with a dented reputation that persists to this day.

Pirate captains played by different rules

While there were plenty of legitimate sailing captains, they weren't the only ones crossing the waves in the Age of Sail. Another sort of captain was out there, one that oftentimes played by a very different set of rules: the pirate captain.

Depending on how, exactly, the ship had come under the command of pirates, its captain may have once been the commander of a once-legitimate ship that had gone rogue. Otherwise, he may have simply been the chief investor in the enterprise — as the one with the biggest stake, he would have had a similar share of decision-making power. Either way, leading the crew would have required a very different approach than what was used by many hierarchy-obsessed naval captains. Indeed, a fair number of the crewmembers might have turned pirate because they were sick of the ill-treatment that had received while serving under a navy captain.

On a pirate ship, its leader was often elected to the position and may have often had to use the power of persuasion to get things done, rather than public punishments or demotions. As with other elected positions, he would often have had to project considerable power and charisma. At least he wouldn't have had the stuffed shirts of the admiralty breathing directly down his neck, though there was the ever-present threat of death courtesy of battle or the authorities' gallows if captured, as pirate captains like William Kidd or Blackbeard learned the hard way.