Why Do People's Voices Change As They Get Older?

Most folks would probably agree that it's easy to spot an elderly person's voice. Oftentimes, a person's voice thins out with age, shifts into a higher register, and becomes a kind of breathy, wispy rasp. On the completely opposite side, some people's voices get deeper with age. Take the estimable Sir Christopher Lee, aka Saruman from the "Lord of the Rings" movies, for example. As we can hear from a comparison of 1975 vs. 1997 interviews with Lee, the actor's signature, booming resonance only took form later in life. His elder voice still retained smatterings of a brittle crack but was generally full and low, and very different from his younger years.

Such changes don't only happen to world-class performers, however. Everyone's voice changes over time, far beyond the creaky shift of boys' voices during puberty that makes them feel self-conscious for a couple of years. Moving into early adulthood, then middle age and late life, many voices elevate in pitch, while some descend. It's correct to assume that such changes happen as a result of changes to the body. Cleveland Clinic tells the generally sad-sounding story: The joints in the larynx — aka the voice box — may stiffen with time, and its cartilage can calcify. Vocal cords themselves can become less flexible and drier, and the muscles may become weaker. Problems like asthma and allergies play a role, as well, as does one's posture.

Shrinking, thinning, hardening tissues

Not everyone's voices change over time in the same way. As UT Southwestern Medical Center says, some people's voices start to creak in their 50s, while other people won't show similar signs until their 80s. This should make perfect sense, because bodily health can vary wildly across people of the exact same demographic. Health deficiencies can also be extremely localized, i.e., someone has a powerful heart but janky knees. And the voice, as a creation of muscles, tissues, membranes, cartilage, air flow, etc., is a byproduct of localized physical health.

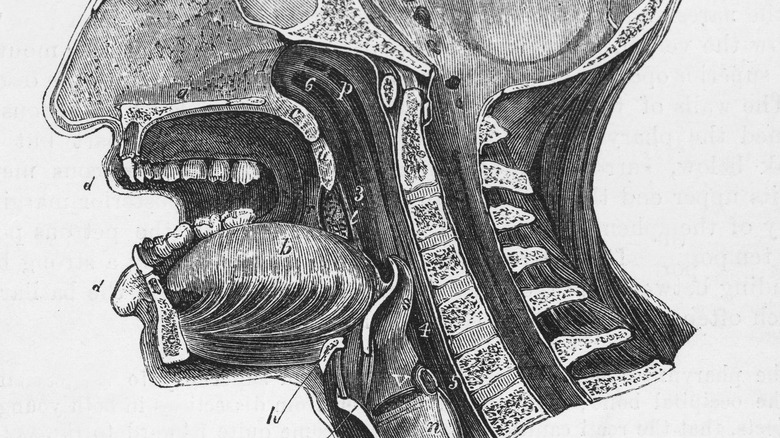

As the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders explains, a multitude of complex elements produces someone's natural, original tone of voice — particularly the length, thickness, and flexibility of vocal folds and the shape of surrounding cavities. The University of Minnesota explains that when someone talks or sings, air travels up the pharynx (the throat), and the vocal folds in the adjacent larynx open up and vibrate like flags in the wind. Faster vibrations produce higher pitches, and slower vibrations produce lower pitches. A person can learn to control the shape and sound of their voice, but innate physiology dictates much of what they will naturally sound like.

Any change to the throat, voice box, etc., changes someone's voice, and muscles shrink with age, mucous membranes thin, and connective tissue like cartilage gets harder. All these changes produce what we recognize as an "elderly voice."

Vocal health and disease prevention

While none of us can stave off the aging process, there are things we can do to strengthen our voice and slow down damage to the entire vocal apparatus. This is especially important for people who have to talk a lot every day, like teachers, lawyers, businesspeople, performers, and so forth. According to the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, people in these professions are at higher risk of vocal deterioration over time.

UT Southwestern Medical Center says that folks can get an examination of their throat, larynx, and vocal cords and enlist the help of a speech-language pathologist. Doctors use specific instruments like laryngoscopes — tubes with little cameras on the end — to examine the vocal apparatus or take slow-motion video footage of the vocal cords as they vibrate. There are also acoustic analyses of the sounds someone makes while talking or singing, as well as laryngeal electromyography, which involves placing little needles into the voice box to measure electrical conductivity.

As far as treatment and prevention are concerned, WebMD suggests humming or singing at home. Use, but not overuse, is helpful. Similarly common sense advice involves not shouting too much, not smoking, drinking enough water, and getting enough sleep. Medical interventions include voice therapy to improve vocal strength and stamina, far more invasive reconstructive throat surgery, and even botox injections and fillers in the throat.