The Real Man Who Inspired Ebenezer Scrooge

Charles Dickens' 1843 book A Christmas Carol is one of the best known and best loved holiday stories of all time, credited with everything from popularizing the phrase "Merry Christmas" to even making Christmas the popular holiday it is today following earlier suppression of the holiday in England by the Puritans. Remember that movie The Man Who Invented Christmas? Yeah, that's what that title's getting at.

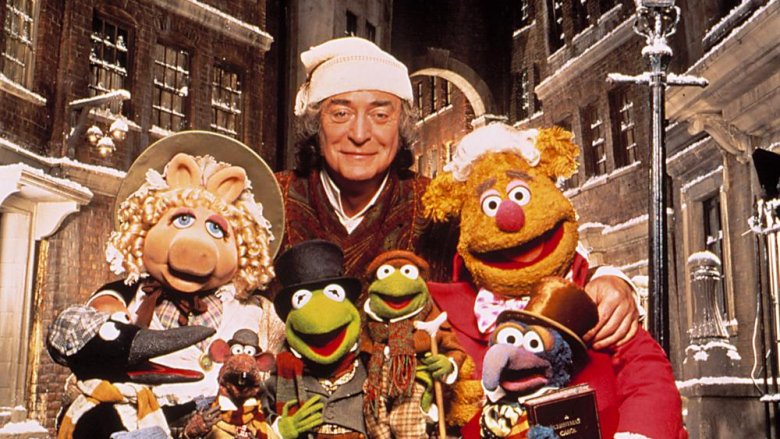

A big part of the success of A Christmas Carol comes from the vivid portrayal and dramatic character arc of its central figure, Ebenezer Scrooge. Scrooge has become an unquestionable icon of Christmas, portrayed on screens big and small by such formidable actors as Alastair Sim, George C. Scott, Michael Caine, Patrick Stewart, and, uh, Jim Carrey. And, of course, his namesake, Scrooge McDuck, who carries on the tradition of thrift despite great wealth. But where did Scrooge come from? Where, Charles Dickens, do you get your ideas?

The Man Who Invented Christmas posits that Dickens based Scrooge on his own father. While that's certainly within the realm of possibility, Dickens' father is more widely acknowledged as the inspiration for the character Mr. Micawber from the semi-autobiographical David Copperfield. And there are a couple of other, stronger candidates that have been suggested over the years for Scrooge. Who, then, is the man behind the miser?

The Stingiest Man in Town

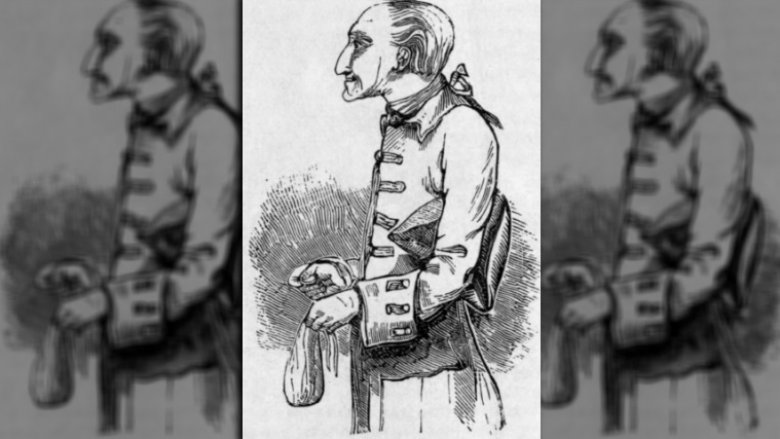

While there are many different men that modern fans claim to be the inspiration for Scrooge (some of them championed by the citizens of these men's hometowns hoping to drum up some tourism dollars — a shameless cash grab that Scrooge would no doubt approve of — the most likely candidate is an 18th-century British politician named John Elwes who was notorious for his penny-pinching. Supporting the idea that Elwes was the model for Dickens' most famous miser is the fact that we know for sure that Dickens knew of Elwes, despite the latter dying years before Dickens was born: Dickens mentions Elwes and his parsimonious habits in his letters as well as referencing him in his last complete novel, Our Mutual Friend. (Dickens wasn't the only one, either. William Harrison Ainsworth is believed to have based his character John Scarfe — the titular miser from his novel The Miser's Daughter — on Elwes as well.)

John Elwes was born John Meggot in 1714 and inherited his first fortune (worth about $10 million today) at just 4 years of age following the passing of his father, a brewer. But he really struck it rich after spending his life imitating and sucking up to his uncle, Sir Hervey Elwes, a wealthy member of Parliament and himself an infamous miser. Meggot changed his name to Elwes to curry his uncle's favor, and he found himself the recipient of an estate worth roughly $23 million today. But if, as they say, a penny saved is a penny earned, John Elwes was more like a billionaire.

Extreme penny-pinching

The young Elwes learned much of his miserly mindset from his uncle (though his mother, who reportedly starved to death because she refused to buy food despite being rich, probably played a role as well), with whom he would sit around complaining about the way other people wasted money while sharing a single glass of wine between them. Elwes took these lessons to heart and took thrift to a comical extreme. For example, Dickens said of his literary miser that "Darkness is cheap, and Scrooge liked it," and Elwes thought the same. He would always go to bed as soon as the sun set so he wouldn't have to pay for candles. He ate roadkill (including a bird that a rat pulled from a river) and would eat moldy and rotting food rather than let it go to waste. He wore ragged clothes, including a wig he found in a bush. His look was so busted that strangers often assumed he was a beggar and would drop pennies in his hand.

He would walk in the rain rather than paying for a coach, and then he would sit around in his wet clothes rather than waste fuel building a fire to dry them. His roof leaked and his lavish home fell to ruin around him. He got mad at birds who stole hay from his fields to build their nests. These all sound like jokes, but this is just what the dude was like.

The politics of parsimony

This might be the wildest Elwes story of them all, actually: Elwes once cut both of his legs badly while walking home in the dark (of course). Being distrustful of doctors, he would only let the apothecary treat one leg, setting out a wager. If his untreated leg healed faster than the treated leg, the apothecary would forfeit his fee. As it happens, the untreated leg healed two weeks faster and presumably Elwes was as smug as some kind of 18th-century anti-vaxxer.

Anyway, like his grandfather and uncle before him, Elwes ran for Parliament and served three terms. He was technically a member of the Whig party, but he would — surprise — vote for whichever party's policies seemed most frugal. Other members of Parliament joked that they would have called him a turncoat, but they knew for a fact that he only owned one coat. He would travel to Parliament by the long route to avoid toll roads. He would ride his underfed horse to work, stopping along the way to eat a hard-boiled egg he kept in his pocket and take a nap under some bushes.

After a total of 12 years in Parliament, he decided to retire rather than continuing to pour out money in running for public office. Considering his election expenses were a staggering 18 pence (less than $2 in today's money, probably? British money from history times is weird), it's no surprise he'd want to relieve himself of that burden.

Not very Scrooge-like

If you look at Elwes' life more closely, however, the Scrooge comparisons start to fall away once you get past extreme personal frugality. When it came to other people, it turns out, John Elwes could be generous with his money. When his friends were in dire financial straits, he would be generous to a fault with his assistance. Furthermore, while he would lend money freely, he was too polite to ever ask his friends to repay him. One story says he once lent a friend £7,000 unprompted so the friend could bet on a horse race. Elwes himself showed up at the racetrack with nothing to eat for the whole day but a two-month-old pancake he found in his coat pocket that he swore was "as good as new."

Elwes also spent a lot of money in investments, some bad, many good. Most notably, he was a patron of architect Robert Adam, and as such financed a lot of London's West End architecture, including Portman Square and parts of Oxford Circus, Piccadilly, Baker Street, and Marylebone. So if you've ever enjoyed any of those places, you can thank the generosity of England's most famous non-fictional miser.

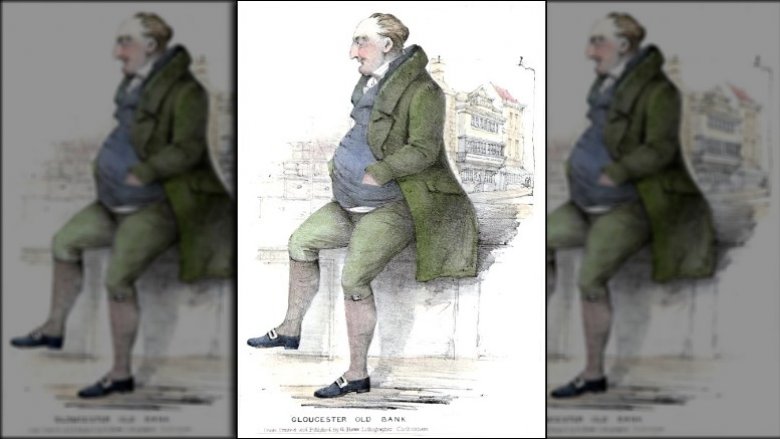

The Gloucester Miser

There are those, however, who argue that John Elwes is not the inspiration (or, at least, not the only inspiration) for Scrooge. Those people will point toward one Jemmy Wood, the owner of the Gloucester Old Bank and possibly Britain's first millionaire, known in his lifetime as "the Gloucester Miser." He, like Elwes, was definitely known to Dickens, as the author also mentions him in Our Mutual Friend. Additionally, there is a character called "Dismal Jemmy" in The Pickwick Papers, and a court case in Bleak House is believed to have been inspired by legal battles over Wood's will that ran so long they ended up consuming most of his estate.

Famous tales of Wood's parsimony include his visiting the docks in order to fill his pockets with coal that fell off boats being unloaded there, and that he walked everywhere instead of ever taking a carriage. Like Elwes, he would wear the same clothes for years until they became ragged. One story says a fellow traveler refused to believe that the raggedy Wood had any money in the bank, and so Wood bet him he could withdraw £100,000 when they got to the city. When Wood was able to procure such fat stacks, the incredulous traveler was forced to hand over his £5. Another story says he once hitchhiked to town in a hearse, riding in the back where the body was supposed to lie. Yes, they're legends, but rich people are wild, honestly.

A Dickensian hoax

Yet another story of Dickens' inspiration for his famous miser comes from a legend so widespread that even the BBC reported it as a possibility. The story goes that Dickens was walking through a graveyard in Edinburgh and came across a tombstone that belonged to one "Ebenezer Lennox Scroggie." The inscription underneath read that Scroggie was a "meal man" — that is, he sold corn — but Dickens misread it as "mean man," and his imagination was sparked by wondering just how stingy someone would have to be ("mean" here meaning cheap) for this to be the way they would be remembered through eternity. The story then goes on to say that the "real" Scroggie was in fact a jolly bon vivant who had a reputation as a party animal who once goosed a countess in church and birthed illegitimate children with his servants. Alas and alack, the story goes, this incredibly very real tombstone from an absolutely non-fictional person who actually existed, super coincidentally was destroyed when the Edinburgh graveyard in question was being restored in the 1930s, but yes, real people very definitely intend to build a memorial in its place any day now.

As the Telegraph points out, this popular story is almost certainly a hoax. The only source for this story is the man who originally told it in 1997, and there is no corroborating evidence whatsoever. He'll probably laugh himself into his own grave if that memorial to "Scroggie" ever does get built.

Surplus population

Scrooge has more characteristics than just his miserliness, however. He is also cruel and antipathetic to the poor in an extreme degree. When, at the beginning of A Christmas Carol, he is asked if he might donate to aid the poor, Scrooge asks angrily, "Are there no prisons? ... And the Union workhouses? ... The treadmill and the Poor Law are in full vigour, then?" When the collectors respond that not everyone can go to these places, and many would rather die than go, Scrooge replies, "If they would rather die ... they had better do it, and decrease the surplus population."

For some critics, including this piece from Forbes, that phrase "surplus population" is a sure sign that Dickens' portrayal of Scrooge was a commentary on the still-current (then and now, to be completely honest about it) debate around the philosophies of political economist Thomas Malthus. Malthus argued that economies and populations grow at different rates, and as a result, poverty is inevitable. The only solution in Malthusian thought is to limit population growth, which leads into some incredibly not-at-all terrible ideas like eugenics and what have you.

Scrooge later feels shame at his earlier Malthusian ideas when the Ghost of Christmas Present refers to Tiny Tim as "surplus population." This Ghost, with his cornucopia a symbol of plenty, stands as a stark repudiation of Malthusian ideas: There is, he says, enough for everyone. You just have to share it. Fortunately, this is a concept Scrooge comes around to after a vision of himself becoming surplus.

Getting warmed up

While there are certainly compelling arguments to be made that Dickens was inspired to create Scrooge by real-life misers and cruel philosophers, it can also be argued that Ebenezer Scrooge was simply the logical culmination of the development of certain ideas Dickens had already introduced in characters in some of his earlier works.

For example, in Martin Chuzzlewit, written in serialized form between 1842 and 1844 (during which period Dickens would have written A Christmas Carol), there is a rich old man named Martin Chuzzlewit who is paranoid about his fortune, fearing that his family has designs on his money. (He's right.) He adopts an orphan to be his caretaker, with the understanding that he will take care of her financially as long as she tends to his health. When old Martin's grandson (also named Martin) falls in love with his grandfather's caretaker, the old man is furious and this is kind of the inciting incident for all of young Martin's adventures and personal growth. Anyway, not to spoil a 170-plus-year-old book, but old Martin is revealed to actually be good and kind at the end of the book, in a character shift that prefigures Scrooge's own evolution.

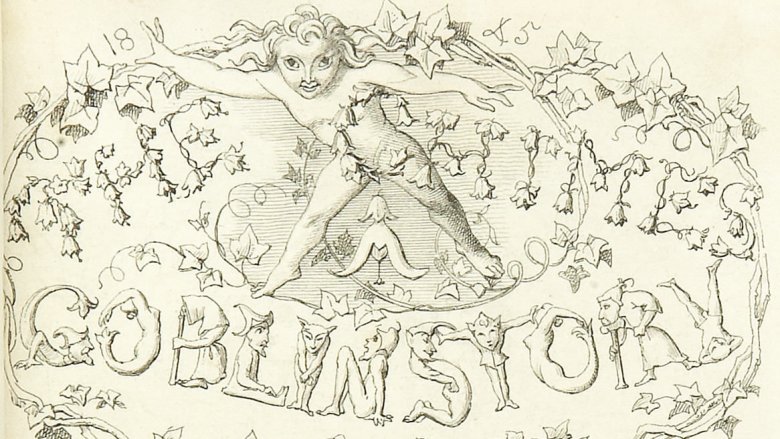

More to the point, in an earlier Christmas story that appeared in The Pickwick Papers some seven years before A Christmas Carol called "The Story of the Goblins Who Stole a Sexton," a Christmas-hating gravedigger named Gabriel Grub is kidnapped by goblins (not ghosts) who show him what Christmas is all about.

A Scrooge by any other name

Charles Dickens is famous for giving his characters colorful, memorable, and descriptive names. Many of these are meant to reveal something about the character's ... well, character, such as Wilkins Micawber from David Copperfield, Mr. Sowerberry from Oliver Twist, Canon Crisparkle from The Mystery of Edwin Drood, and the ultra-subtle Mr. M'Choakumchild from Hard Times. "Ebenezer Scrooge" is one such name, where even the sound of it evokes a not particularly pleasant person. But might there be a significance behind the name beyond just the sound of it?

"Ebenezer" is a Biblical word, appearing in 1 Samuel 7:12. There it is a stone set up by the prophet Samuel to commemorate the help that God gave the Israelites in their victory over the Philistines. "Ebenezer" is an Anglicization of the Hebrew "ebhen hā-ʽezer," meaning "stone of help." Today if the word is used in a non-Scrooge context, it usually means any kind of remembrance of God's help, as in "Here I raise mine Ebenezer" from the hymn "Come Thou Fount of Every Blessing." While arguably a stretch, Dickens' Ebenezer definitely receives divine help in overcoming his worst impulses.

Similarly, "Scrooge" might be a take on the word "scrouge," meaning to squeeze, recalling Dickens' description of Scrooge as "a squeezing, wrenching, grasping, scraping, clutching, covetous, old sinner." Likewise, "Scrooge" sounds like "screw," which was an old British slang word for a miser.

An alternative theory worth entertaining is that "Ebenezer Scrooge" just sounded good, so he went with it. They can't all be "Anne Chickenstalker."

Variations on a theme

Although A Christmas Carol is definitely Dickens' most famous Christmas story — and, indeed, probably the most famous Christmas story not found in the Bible — it's certainly not his only one. He would go on to write several more, occasionally trying to catch that Scrooge lightning in a bottle again.

Besides the earlier "The Story of the Goblins Who Stole a Sexton," which was almost a first draft for A Christmas Carol in a lot of ways, in 1844, the year after Carol, came The Chimes, a story in which elderly messenger Trotty Veck is shamed by goblins for losing faith in the goodness of humanity and their capacity for self-improvement. 1848's The Haunted Man and the Ghost's Bargain is extremely Scrooge-esque, with chemistry professor Redlaw obsessed with griefs and embarrassments from his past and making a deal with a ghost to forget all of these things. Suffice it to say, this doesn't go well for Redlaw, and after his ghostly encounter, like Scrooge, he is a better, more loving person. It would be pretty fair to say that from Gabriel Grub to Ebenezer Scrooge to Trotty Veck to Professor Redlaw, the idea of a cynical or selfish person who is improved by an encounter with the supernatural is a theme Dickens was interested in trotting out some variations on.

(Dickens' other Christmas books, the well-loved The Cricket on the Hearth and The Battle of Life don't really follow this pattern, and in fact, Battle doesn't have any supernatural elements at all and is barely even about Christmas.)