The Untold Truth Of The 1969 Royal Family Documentary The Queen Banned

In 1969, the BBC aired a shockingly intimate documentary called "Royal Family." As the title suggested, it was an unprecedented look at the daily life of Queen Elizabeth II, Prince Philip, and their children, pulling back the curtain on the monarchy in a way that had never been done before. It was watched by millions of people, and then it was buried in the BBC's archives and rarely seen again. The story goes that the royal family themselves put a halt to the documentary's broadcast, but even information on that is a little sketchy. Rumor has it that what was featured in the doc was much too revealing.

It sometimes pops up on YouTube, but it's often taken down just as quickly. Anyone fortunate enough to catch it will be treated to a behind-the-scenes look at a year in the life of the royals. They're seen starting their day behind desks piled high with paperwork, the queen takes little Prince Edward to the candy shop, the family sets up a picnic and enjoys a snowball fight, and of course there are puppies. It's not all that relatable, though, and some attempts at seeming in-touch with the average British family fall incredibly short. They sit around the television and enjoy the Christmas holiday... but they do that at a handful of castles. So, what's the deal with this weird piece of royal history?

The documentary was planned with the investiture of Prince Charles in mind

Queen Elizabeth II was the head of the British monarchy for so long that it's easy to overlook a lot of things, starting with the fact that it's not a rule that the monarch's eldest son becomes the Prince of Wales. The title goes back centuries, and it's up to the monarch to hand the position out: King Charles III gave the title to Prince William shortly after Elizabeth's death, and in 1969, the young Charles had been made Prince of Wales in an official ceremony (pictured). Everyone had been preparing for it since he was a wee, 9-year-old prince, but here's the thing: At the time, the Welsh people weren't incredibly fond of the monarchy.

And that's kind of an understatement. Welsh nationalists went as far as planting a series of bombs around Wales to disrupt Charles' investiture, accidentally killing two of the bombers and severely injuring a young boy who found an undetonated bomb days later.

The documentary was pitched as a way of introducing the new Prince of Wales to the country, and to improve public opinion of the family. The idea came from Lord Brabourne — the son-in-law of Philip's uncle Lord Mountbatten — who had already spent years working in the entertainment industry. He'd begun working as a producer fairly recently when he suggested filming a documentary to give the queen's subjects a look at who she really was. The idea wasn't exactly met with enthusiasm... at first.

Not everyone was a fan of the idea

A few people in the royal household got on board in a huge way, starting with William Heseltine. At the time, he was Buckingham Palace's press officer, and believed that a documentary showing the royal family hard at work for the benefit of Britons everywhere would be a great way to make them seem more relatable.

Heseltine and Lord Brabourne, who originated the idea in the first place, got Prince Philip to agree to the plan first. Elizabeth herself was a harder sell, and even when she agreed to it, she still wasn't certain that it was a good idea. Heseltine explained (via Town & Country), "The Queen was a reluctant convert, but became much more aware of the possibilities and was prepared to participate when it came to actual filming. And I had among my three private secretarial colleagues one enthusiast, one definitely opposed, and one with one foot on either side. So it was quite an interesting time."

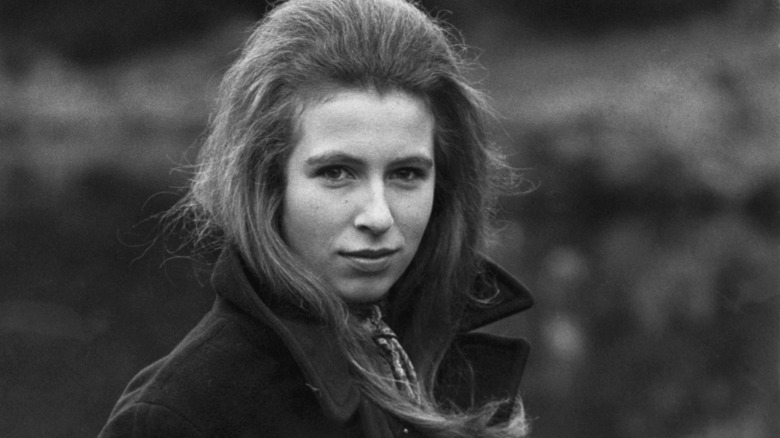

Others were downright opposed to the idea, and Princess Anne (pictured) shared her thoughts on the matter in a 2002 documentary. "I certainly never liked the idea of the royal family film. ... The attention that had been brought on one ever since one was a child, you just didn't want any more. And the last thing you needed was greater access. I don't remember enjoying any part of that."

For some context, here's how new television was

To 21st century eyes, it might seem odd to argue over something as seemingly normal as a carefully edited, behind-the-scenes documentary, but context is important. At the time the royal family was debating on whether or not to film the documentary that would become "Royal Family," television was still a relatively new medium. It was so new, in fact, that for many people, it would be the first time they'd ever hear the members of the royal family speak.

It was only a few years prior that Prince Philip had become the first royal to be interviewed on television. He appeared on the documentary-style news program "Panorama" in 1961, and even though it was something of a softball topic — the need for more skilled workers — it was a huge deal.

It also made the Duke of Edinburgh more tuned in to the power of television, and in 1966, he allowed the filming of a documentary on the royal palaces. He saw the medium as an invaluable tool that could be used to give the monarchy a much-needed makeover, saying (via History Extra) that a documentary was a brilliant way of presenting the royal family not as some aloof, holier-than-thou force to be obeyed, but as ordinary people. Who just happened to have castles.

It was seen as an attempt to revive the popularity of the monarchy

Questions about whether or not the world still needs a British monarchy have been circulating for a long time, and although Queen Elizabeth II was pretty popular at the time of her death, the 1960s were a rough time for the royals. They were seen as uncaring and distant when tragedy struck the Welsh coal mining town of Aberfan; 28 adults and 116 children were killed when a landslide of mining waste engulfed a portion of the town, and it wasn't until eight days later that Elizabeth finally made the trip to console locals (pictured). With Charles' investiture as the Prince of Wales coming up, something needed to be done. According to historian Sarah Gristwood (via History Extra), the documentary was meant to convince the public that the royals weren't as expendable as they feared people were starting to think.

Worries had been there for a long time, going back to World War I and the rebranding of the royal family from their German roots to the more British-sounding Windsors. By the late 1960s, those in the know decided to turn to more creative ways to make the monarchy seem like more than a cash grab by people who were already way too rich.

The Independent even quoted a former private secretary to the royals as saying, "We only did [the documentary] just in time, though. I don't think we'd have survived if we hadn't done it."

The royals struggled with being filmed

There's a scene in the documentary that shows the royal family preparing a picnic, making salad, and grilling sausages. With their vaguely annoyed tones and a prince — Edward, little more than a toddler — who won't stop demanding to know what spoons are for, it's one of the most relatable parts of the entire film. It was also about when producer and director Richard Cawston realized that the doc's biggest proponent, Prince Philip, was not a fan of the filming process. Then-press secretary William Heseltine rather diplomatically explained (via Town & Country), "Prince Philip became less enthusiastic when it came to being filmed himself, which he hated." At one point, in fact, Philip reportedly snapped at the crew: "Get away from the queen with your bloody cameras!"

Elizabeth, too, was supposedly not thrilled with the filming for a few reasons: Not only was she very protective of the family's personal space and private times, but — surprisingly, for a monarch who saw so much of it — she was highly opposed to change. Opening the family to a television crew? That was a big one.

While Charles doesn't seem to have directly commented on the making of the documentary, he did make some very telling remarks released in the lead-up to his coronation (via The Telegraph). He described himself as being "a private person," and one who hated the times that he had been forced to become a "performing monkey" for the media.

It was more scripted than it seemed

The documentary was ultimately presented as a look at a year in the life of the royal family, and in addition to painting themselves as invaluable, they were determined to seem relatable. All of that ended up meaning that the whole thing was much more scripted than it was originally intended to be.

The documentary was produced by the BBC's Richard Cawston, who was ill-prepared for the difficulties of working with the royal family. According to the Independent, he had completed several months of filming when he realized just following them around and cutting a film together in the end wasn't going to work out. The idea of documenting a year in the family's life was pitched to him, but there was a problem: It was already autumn. The solution? Fake a summer-time picnic to splice in, to make it look like they were being chronologically accurate.

The man who pitched the idea of a chronological look into the royal family's life was ultimately hired to script the documentary. That was Antony Jay (who fans of British television might recognize as the writer of "Yes, Minister.") Generic shots of, for example, parades and processions were given voice-overs explaining what was going on in the scene, giving historical context, and editorializing about the importance of the monarchy. Some royal activities were very carefully not included. Among the things on the no-go list were any scenes of the royals hunting, out of concern that it would make them seem elitist.

The one scene that almost didn't make it

It's understandable that the royal family would have wanted the final say in what got included in the documentary and what didn't. But it's also easy to see how that might have made life miserable for anyone trying to film them, so once producer-director Richard Cawston had a heart-to-heart with Prince Philip, part of the deal was that Cawston would be in charge of filming — and with that went adherence to his long-standing rule of not showing anyone raw footage of an in-progress work.

According to the Independent, even the royals didn't get to see the documentary until after filming was finished. That meant what they saw was pretty much what they got, and there wasn't time for reshoots or to script entirely new scenes. Fortunately for producers, that worked out all right, and there was only one scene that led to a massive disagreement about whether or not it would air.

The scene in question featured Charles playing the cello with the seemingly inevitable interference from his little brother, Edward. It's a sweet scene where Charles explains how the shape of the instrument creates the sound, but when one of the strings snaps and strikes Edward in the face, it brings the younger prince to the verge of tears. While Philip wanted to veto the entire scene, Elizabeth overruled him and allowed it to stay.

It's been ridiculously popular... and elusive

It's unclear just how many people have seen 1969's "Royal Family," but the BBC estimates that when it originally aired, it netted somewhere around 350 million viewers around the world, with the Independent citing approximately 22 million domestic viewers — enough to cause a rush on the nation's water system as everyone hurried to the bathroom during the mid-movie break.

But after a few airings, it essentially disappeared. The reason seems to lie with the royal family themselves, although details are scarce. Queen Elizabeth retained not only the copyright for the film, but strict control over what can be seen again — as evidenced by the documentary's very brief reappearance on YouTube in 2021, and the quick disappearance that followed. For years, it's been forbidden to rebroadcast the documentary in any way, shape, or form, although occasional exceptions have been granted. For the queen's Diamond Jubilee, for example, the National Portrait Gallery was granted permission to show a specific, 90-second clip. Anyone wanting to view the entire documentary for research purposes was required to do so at the BBC's London headquarters, and could only see it after getting permission from Buckingham Palace and paying a fee of around $40.

Why it was such a big deal, and why it was banned... maybe

There's no single, definite answer as to why "Royal Family" disappeared from public accessibility, and it's something that seems even stranger to 21st century viewers, who are accustomed to high-profile figures making messes over themselves on social media all the time. After all, there's nothing too terrible about the documentary — except, perhaps, the casual way Elizabeth points to fist-sized jewels and requests clothing to be made in the same color. Eye-roll inducing, perhaps, but not career-ending. So what was the big deal?

One hint comes via David Attenborough, who was the controller of BBC2 at the time the documentary was broadcast. He cautioned against revealing too much of the inner workings of the royal family, warning (via the Independent), "The whole [monarchy] depends on mystique and the tribal chief in his hut. If any member of the tribe ever sees inside the hut, then the whole system of tribal chiefdom is damaged and the tribe eventually disintegrates."

Journalist Clive Irving has similar things to say in a piece for the Daily Beast. He wrote that although Queen Elizabeth was a highly recognized and widely known figure, few people knew who she actually was. She never expressed things such as her personal political views, for example, and there was little to separate her from the images that appeared on currency and postage stamps. The documentary, Irvings suggests, was something a little too personal that broke the distant, regal majesty of the monarchy.

Unaired footage has never been shown, even though the queen kind of liked it

The final cut of the documentary was edited down to just around two hours, and "edited down" isn't an exaggeration. Film crews spent 75 days with the royal family, and even more impressive than that, they visited 172 different locations. It goes almost without saying, then, that there's a ton of footage that's never been broadcast, and it seems likely to stay that way in spite of the fact that when the family was shown the final product, it's said that Queen Elizabeth was pretty fond of the way it turned out.

The documentary's editor, Michael Bradsell, says (via Harper's Bazaar) they were all incredibly nervous about sitting down and showing the finished product — and understandably so. "We had no idea what she would make of it," he said. "She was a little critical of the film in the sense she thought it was too long, but Dick Cawston, the director, persuaded her that two hours was not a minute too long."

Will the entirety of the footage ever be available? That's impossible to predict, but it's worth noting that since the death of Queen Elizabeth, some previously unseen footage has made it into other productions. Ahead of the coronation of King Charles III, the BBC was permitted to break open the archives and use some of that 1960s-era footage in a new documentary about his life.

How accurate was the information in The Crown?

If the goal of "Royal Family" was to humanize the monarchy, historians say that it was a success: It showed the family in a new and more accessible light. But it's entirely possible that it did its job a little too well. Biographer Hugo Vickers explained (via Harper's Bazaar): "Some people say that this would open the floodgates, and therefore after that all the sort of tabloid interest in them [would follow]."

It can be argued that that interest led to "The Crown," so it's fitting that the show mentions the documentary in a big way. Unfortunately, one of the show's most fascinating beats concerning "Royal Family" isn't true in the slightest, and that's the claim that a naysaying reporter from The Guardian was invited to interview Princess Anne after writing a scathing condemnation of the documentary, only to end up interviewing Philip's mother, Princess Alice (pictured), instead.

That absolutely didn't happen, starting with the fact that The Guardian didn't even have any harsh words about the documentary. Even sadder is the fact that between Alice's 1967 arrival in Britain and her death in 1969, she was hardly mentioned in the press at all, in spite of living a fascinating life that included being diagnosed as both deaf and schizophrenic, being a patient of Sigmund Freud, sheltering a Jewish family during World War II, and founding the Christian Sisterhood of Martha and Mary. She did not, however, achieve the notoriety her fictional counterpart received in "The Crown."