What It Was Really Like To Be One Of The First Female Astronauts At NASA

"It's time that people realized that women in this country can do any job that they want to do." These were astronaut Sally Ride's words, reflecting on her experience as the first American woman to travel into space. In one small step, she influenced an entire generation of women for whom she became a role model practically overnight. She was one of NASA's first six women astronauts, together with electrical engineer Judy Resnik, oceanographer Kathy Sullivan, chemist and medical doctor Anna Fisher, surgeon Rhea Seddon, and biochemist Shannon Lucid.

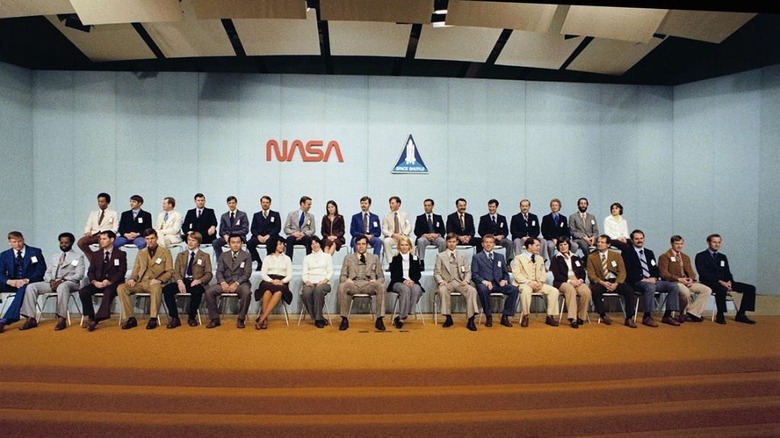

They were part of a historic group of new astronauts recruited by NASA in 1978. NASA's 8th group of astronaut recruits needed people specifically to crew the space shuttle, which would have its inaugural flight into orbit in 1981, and many recruits were scientists and engineers for the brand-new mission specialist role at NASA. Most notably, this was the first time women and people of color were ever chosen for American space missions.

The diversity of NASA's class of '78 made them immediately stand out from previous groups. Under instruction from President Dwight D. Eisenhower, all previous astronauts had been test pilots selected from the military and were exclusively white and male. Nearly all had been on active military duty, and those who weren't (like Neil Armstrong), had been military pilots previously. Astronaut Group 8 stood in stark contrast by including civilians, with doctors and academics. It spelled big change for both NASA and American spaceflight as a whole.

Childhood dreams made real

By the 1970s, people around the world had grown up watching news about rockets on television and seeing space travelers like Yuri Gagarin and Buzz Aldrin make their journeys into orbit. These stunning events captured the imagination of an entire generation of people. For many, it became a childhood dream to become an astronaut, but many thought that dream would be impossible.

This included Anna Fisher, who'd been inspired by seeing Alan Shepard, America's first astronaut. In a later NASA Q&A, she explained that she considered it unrealistic at the time, saying, "It just seemed like a dream that wasn't going to be possible." Others had already given up on that dream. Sally Ride, who'd later gain fame as an astronaut, never even considered a NASA career. She simply didn't think women would or could ever be admitted to work there. Some, though, kept going out of optimism. As a child, Shannon Lucid had dreamed of growing up to be an explorer but had worried there would be nothing left for her to explore. Inspired by reading science fiction, she'd decided to become an "explorer of the universe."

Becoming an astronaut hadn't been a childhood ambition for all of the recruits though. The applications were open to anyone who qualified, and for the exceptionally skilled Judy Resnik, applying was more about looking for an interesting new experience. She heard about it completely incidentally and decided to apply, just to take a chance and see what might happen.

NASA was actively looking for women and minorities

NASA has always been all about exploring new territory, but the call for Astronaut Group 8 needed them to break a different kind of ground. Following the civil rights movement of the 1960s, the agency was making an active effort to improve its diversity for the first time. It took out advertisements in places specifically chosen to reach a wider variety of people, including in popular Black culture magazines like Jet and Ebony. Most notably, NASA hired Nichelle Nichols, famous for her inspirational role in "Star Trek," as part of a recruitment campaign. In one TV advertisement (via YouTube), she makes a point of saying, "I'm speaking to the whole family of humankind, minorities and women alike — if you qualify and would like to be an astronaut, now is the time."

As well as reaching out through pop culture, NASA was also aiming to hire scientists and engineers, so no small amount of their advertising was directed towards universities and academics. This was how some of the class of '78 first heard that NASA was recruiting, like Kathy Sullivan, who first saw an advert in a scientific journal. Once the news reached college campuses, word also spread organically. Others, like Anna Fisher, first heard the news this way. She never saw any adverts herself, learning about it by word of mouth just three weeks before the application deadline.

Applications were incredibly competitive

NASA's call for astronaut recruits had the potential to be a dream come true for countless people across America. As you might expect, the competition was fierce, and the agency made a point to be certain all their applicants met all of the requirements and specifications. Speaking with the NASA Johnson Space Center Oral History Project, Kathy Sullivan recalled how the process took a few steps, explaining that "if you sent the first inquiry in, they sent you back a postcard or short communiqué that basically read, 'This is just to make really sure that you're really sure.'"

Even with the convoluted process, the number of applications was overwhelming. Between the summers of 1976 and 1977, NASA received inquiries from over 24,000 people, sending out over 20,0000 application packages in response. They received a total of 1,142 applications from female candidates. By 1978, from all their applicants, they'd picked out 208 people to interview.

Applying to work at NASA potentially meant a sudden and drastic change for the applicants, both for their careers and their entire lives. Speaking with NASA Johnson, Anna Fisher explained how she was hesitant to even apply, having already accepted a surgical residency and wondering whether it was worth uprooting her entire life. She also recalls how her superiors at the time treated the idea with some scorn — until she was actually accepted.

The announcement made the six women famous overnight

In the latter decades of the 20th century, the world was still adjusting to women taking on professional roles. The announcement that six women had been recruited as astronauts — an area that had previously been purely male-dominated — made a massive impact. The six female recruits were completely swamped by reporters trying to speak with them. As soon as her name was made public as an astronaut recruit, Judy Resnik received over 100 requests for an interview. Even before NASA had made any official announcement about their new group of astronauts, the press had gotten hold of their names. Reporters dogged the recruits relentlessly, including showing up at their workplaces completely unannounced and calling their homes.

At the time, one thing that NASA was in serious need of was publicity. The space shuttle project was still new, and none had even been launched into space yet. Some of the recruits, like Anna Fisher, were perfectly happy to get involved with the more public side of being an astronaut, considering it just part of their jobs. For others though, it was probably quite a shock to the system. Sally Ride's friends have since described her as a "fiercely private individual," which no doubt made all of the media attention a lot to have to deal with.

The press still leaned heavily into stereotypes

While the press seemingly couldn't get enough of NASA's six women recruits, they could also be terribly condescending. One example was when Judy Resnik was invited for an interview on "The Today Show" (via YouTube), in which her interviewer made a point to introduce her with the line "she's single," before repeatedly asking clichéd gender-based questions.

The women mostly had to take this in their stride. In another TV interview (via YouTube), Sally Ride once said, "I don't mind people asking me questions about what I'm going to do on orbit, and whether I'm going to be doing any of the cooking on orbit, unless it's asked by someone who expects that the only reason I'm flying is because Crip needs somebody to serve him coffee" — referring to Mission Commander Robert L. Crippen.

While all were careful to maintain a pleasant demeanor while being publicly interviewed, they were understandably unhappy with the way they were being treated by the media. Rhea Seddon later mentioned that some of the women did indeed take offense at the press leaning into chauvinism, by focusing on irrelevant details like their clothing. Seddon was resigned not to let it bother her because it was out of her control, but that part was precisely what bothered Resnik the most. She tried to avoid the press because she had no control over when they'd venture into territory she considered too personal.

Thirty-Five New Guys

NASA's class of '78 was the first astronaut group to be given an official nickname, TFNG. On the record, this stood for "Thirty-Five New Guys," but everyone knew it was really derisive military slang for new recruits. In retaliation, the recruits started referring to their predecessors as "the old guys," much to their chagrin. Only 29 of the new recruits were, in fact, guys, but the women recruits were happy to lean into the nickname, keen to just blend in with the guys rather than to stand out. Some, like Fisher and Ride, made a point of going shopping for khakis and shirts, so they'd look the part too — the kind of clothing that may seem unremarkable for women to wear in the 2020s but was still largely unthinkable not so long ago.

The women may have been trying not to stand out, but that didn't stop them from getting excessive attention from the media. During any kind of public event, the focus was mostly kept on them and, to a slightly lesser extent, on the non-white men who NASA had recruited. Another of the recruits, Mike Mullane, later wrote about this in his book, "Riding Rockets: The Outrageous Tales of a Space Shuttle Astronaut," mentioning that, "The white TFNG males were invisible." Not all the women were comfortable with the attention either. Judy Resnik, who famously hated the press, always found it unfair that she got so much attention just for being female.

Plenty of people at NASA were skeptical

Speaking with NASA Johnson decades later, Rhea Seddon mentioned, "I've heard some stories about people that were upset that they were going to take women." At NASA, the veterans were skeptical for two big reasons — some doubted that women would be up to the task of working in what they still considered a men's job, while others had their doubts that academics and postdoctoral researchers could perform the roles that only the military had done up until this point. The new group of recruits may have broken barriers simply by being there, but they still had to face a lot of old-fashioned prejudice, and while much came from outside NASA, a fair amount also came from within.

This skepticism feels even stranger with the knowledge that the six women recruited for the class of '78 weren't even the first women to go through astronaut training. In the 1960s, a group known as the Mercury 13 was made up of 13 women who went through the same training as the male astronauts — and often fared better than the men did. One of them, Jerrie Cobb, gave them the nickname of the FLATs, standing for "Fellow Lady Astronaut Trainees." Sadly, none of them ever made it into orbit, but certainly not for lack of ability. Seddon would later note that, had they been born 20 years later, some would certainly have become true astronauts.

The women were welcomed into NASA

Notwithstanding any skepticism within NASA or the condescension from the press, the work environment enjoyed by the new astronaut recruits was a strictly professional one. The women were made to feel completely welcome while they were training and working, to such an extent that some were caught off-guard by it. Speaking with NASA Johnson, Anna Fisher would later recall that, "That was one thing that I was very pleasantly surprised about. Everybody was warm, receptive."

Judy Resnik publicly expressed similar sentiments at the time, mentioning how she hadn't experienced any chauvinism or discrimination while working at NASA, saying, "Everybody leaned over backwards to make sure that we were treated as equals right from the beginning." Where space travel is concerned, everything needs to work efficiently, and it seems everyone directly involved with the astronauts completely understood this. At times, when reporters took their questions too far, the male astronauts weren't afraid to stand up for their colleagues in front of the media. During one press conference (via YouTube), Commander Robert Crippen had to make a point of bluntly clarifying, "Sally's on this crew because she's well qualified to be here."

The training was more demanding mentally than physically

Astronaut training is no quick endeavor. The recruits in NASA's Group 8 trained for four years before any were assigned to actual space missions. This included the kind of extreme-sounding physical fitness assessments you might expect. After all, any astronaut would need to be able to cope with the demands of spaceflight, like g-forces — which involved spending time in centrifuges to be certain their bodies could cope. The astronauts themselves, however, insisted these physical tests weren't as bad as they appeared.

While those outside NASA expected that the physical side of astronaut training would be the most grueling, the astronauts themselves reportedly didn't find it too demanding. When asked, Judy Resnik reflected on how the physical aspects of the training were very gradual, taking things step by step and building up their ability, so they were never subjected to anything they couldn't yet handle. According to Resnik, the most challenging part was being overwhelmed with new skills. Having so many new and different things to learn evidently took a lot of work. For her part though, Resnik clearly enjoyed her training, with old video footage often showing her with a big grin on her face.

NASA had to make accommodations for their new recruits

When the six newly recruited women astronauts arrived at NASA, they did their best to blend in, not wanting to be treated or regarded any differently from their new male colleagues. However, they weren't always able to blend in as seamlessly as they'd have liked. Everything at NASA had been designed with military men in mind, and a few changes needed to be made for some things to be physically usable by the women. Most notably, this included needing to make a new smaller-sized space suit that would fit them properly. In Judy Resnik's words, "One-size-fits-all small size for men doesn't fit small women."

Of all the new recruits, Rhea Seddon had the most difficulty. Standing at just 5 feet 2 inches, she was the shortest astronaut NASA had ever recruited at the time, and it became clear to her during training that there was a lot that had been designed for people no shorter than 5'6. Still, she did her best to make do with everything that was already available, later saying, "I made a real effort to not ask them to redesign the equipment." Overall though, despite NASA needing to make a few small adjustments, the six women mostly got their wish of being treated the same way as the other recruits. In the end, their challenges weren't especially different from those faced by the men in their group.

NASA still didn't understand women

Despite efforts to be inclusive, NASA was still run by men and had a few bizarre misconceptions about its newest recruits. One of the strangest things this led to was when NASA got some of its engineers to design a space makeup kit, based on the personal hygiene kits NASA already routinely sent up with its astronauts. They hadn't asked any of the women about this and had simply assumed they might want things like mascara and lip gloss while in space. Needless to say, the space makeup kit never actually made it aboard a space shuttle — although Rhea Seddon did end up bringing some makeup of her own into orbit, among her personal items.

Another of NASA's famously comical blunders was not knowing how many tampons Sally Ride might need for a week aboard the space shuttle. In a now-famous exchange, an engineer asked if 100 would be the right number, to which Ride replied, simply, "No, that would not be the right number." While it may seem funny now, some of the men working at NASA made a big fuss about menstruation in space, worrying about potential health issues that might ensue. In the end, though, the worry turned out to be needless. Seddon recalled all of this later on, describing it as "another one of those issues that was really kind of a non-issue."

[Featured image by Kenneth Lu via Flickr | Cropped and scaled | CC BY 2.0]

Everyone quietly hoped they'd be first

As the first space launches neared, the astronauts began to wonder who would be the historic first woman chosen by NASA to travel into orbit. After years of training, all were understandably eager to get into space. Rhea Seddon later recounted that most had expected NASA would choose either Judy Resnik or Sally Ride for the role. Deep down though, all remained optimistic. In Seddon's words, "All of us thought, 'Well, maybe it will be me.'" While there may have been quiet conversations about it though, the six women never considered it important enough to discuss between themselves.

Kathy Sullivan echoed the same sentiments when speaking to the NASA Johnson Space Center Oral History Project, saying how the actual decision process at NASA was kept opaque, so no one really knew who would be chosen. Sullivan considered it a waste of her time and energy to worry about it, though she also admitted, "I would have loved to go first." Sally Ride herself, was also hoping but not expecting to be chosen. In an interview (via YouTube), before any astronaut names had been announced, she mentioned, "I'd like to get up as soon as I can [...] but I don't have any great desire to be the first."

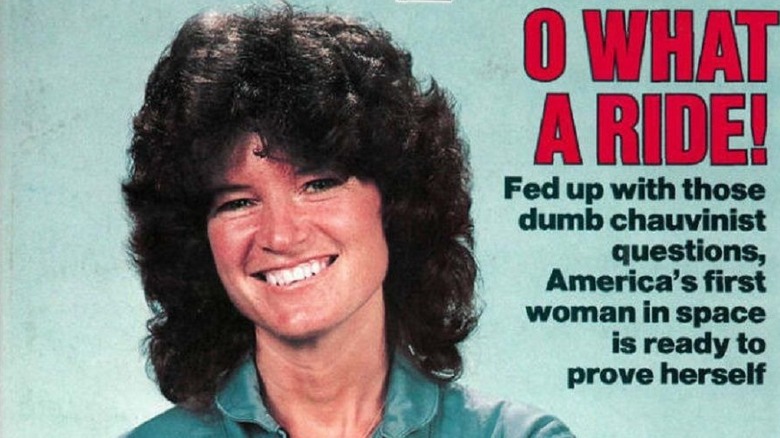

Sally Ride's honor came with huge expectations

While all six women inwardly hoped they all might be chosen to go first into space, all also knew implicitly that whoever was chosen would be under an immense amount of pressure. That was confirmed when it was announced that it would be Sally Ride making that historic space shuttle flight in 1983. Overnight, she shot to stardom. She was featured on the covers of magazines like Newsweek, as the press eagerly reported any and all information they could scrape together.

For Ride herself though, most pressure didn't come from the media. Instead, it came from within NASA, as people all around her were preparing for the shuttle launch. In an old video via Space.com, Ride recalls that the days before her first launch were a blur. She was shouldering quite a burden, and NASA was keen to make certain she understood this. On the day she was selected as one of the shuttle crew, she was also invited to a meeting with Chris Kraft, then head of NASA Johnson Space Center, to make sure she fully understood everything she was getting involved with before she officially agreed to anything. Ride, however, was so thoroughly excited by everything going on that she later admitted could barely remember the conversation.

Ride's first ride

Launch days are when many workers at NASA really feel the pressure. Everything has to work like clockwork for all the teams to coordinate, ensuring everything works properly at launch time. On the day of Sally Ride's launch, there was so much excitement all around her, that she found it difficult to concentrate on what she was supposed to be doing, especially as it came time for her to board the shuttle itself. To manage, she had to do her best to focus purely on what she was doing and try to ignore everything else going on around her.

Ride would be flying on STS-7, the 7th spaceflight of any space shuttle. The fact that this was one of the first shuttle flights was no doubt part of why the atmosphere was so electrified, with the cocktail of excitement and anxiety that comes with trying to ensure everything goes well. Per a video from NASA Solar System, the full reality of the situation didn't hit Ride until she was aboard the spacecraft ready for liftoff. In her own words, "When that hatch shut, I realized, 'Oh my gosh, this is really gonna happen!'" The whole experience, with everything so new, etched vivid memories into her. She recalls with lucid clarity the experience of being in orbit after the engines finally cut off, and being able to look out of the shuttle window for the first time and seeing planet Earth below her.

America's reluctant new darling

Returning after her first space mission, the attention Sally Ride was given was overwhelming. Being an introvert by nature, having the spotlight shining so brightly on her was something she struggled with. Even her colleagues who hadn't flown were astonished by all the hustle and bustle. Kathy Sullivan would later recall seeing an enormous crowd of people, eager to meet the first American woman in space. Looking out at the surrounding furor, Sullivan recalled thinking, "If this is what you get for going first, she can have it" — something she happily told Ride herself.

Even now, after completing a journey into orbit and back, many of the press still insisted on asking Ride demeaning gender-based questions. One of the most infamously condescending was one reporter who, in a press conference, asked her, "When there's a glitch or whatever, how do you respond? [...] Do you weep?" Doing her best not to appear irritated, Ride refused to grace it with any response beyond asking why the men on the shuttle crew didn't get asked the same kind of things. Despite not always being comfortable with the attention she found herself with, Ride still did her best to use her newfound fame to inspire others. This included making a few celebrity appearances on TV shows, including appearing on kids' shows like Sesame Street.

Life aboard the space shuttle

NASA's space shuttle orbiter vehicle needed to be a place where a group of astronauts could spend several days in space, with space missions eventually lasting over two weeks on average. Space travel, however, can be a rough journey at first. For Anna Fisher, it took a day or two of "not feeling great" to properly adjust to weightlessness, during which she found herself wondering why she'd wanted to be there in the first place. When she got used to the lack of gravity though, she found weightlessness was her favorite part of the experience. For Rhea Seddon, the best part of space travel was being able to look outside and see Earth from orbit. She mentioned also, that the cleaning crew for the space shuttle, back down on Earth, would often complain that the shuttle windows always had nose prints on them.

Because of the extended stays in orbit, shuttle life needed to include exercise and group sleeping arrangements. In a video via the National Space Society, Judy Resnik described it as being "a bit like summer camp." One peculiarity of shuttle life, as Resnik explained for ABC News (via YouTube) was the sleep schedule. As well as not matching the sleep patterns of those back on the ground, the astronauts kept a schedule where they'd wake up slightly earlier each day. This was to ensure that, on landing day, they'd be awake early enough to make all the preparations they needed.

The second American woman in space

Remembered less often than Sally Ride, America's second woman to go into space was Judy Resnik. Her first spaceflight was aboard the space shuttle Discovery, on mission STS-41D, but her experience didn't go quite as smoothly as Ride's. The first launch attempt of her mission needed to be canceled because of a fire on board the orbiter vehicle. By now though, Resnik was a fully trained member of NASA personnel, so she approached this with a degree of measured pragmatism, simply being pleased that the safety precautions all seemed to be in order.

Resnik was also the first Jewish person ever to go into space. During her training, she'd become exceptionally skilled at operating the mechanical arm in the space shuttle's cargo bay, used for loading and unloading items while in orbit. During her first mission, her main job was to manage an experiment involving a solar sail; a huge panel for collecting solar energy, as Resnik explains herself in a video from the National Space Society, at the time this was the largest single structure astronauts had ever deployed. Her early experiment was a predecessor to the solar arrays still used by spacecraft today. At the time, the goal was to test the technology for future space stations NASA intended to build.

The following shuttle flights

After Sally Ride's ordeal with the press and all of their gender-related questions, the media began to relax a bit. Now that women traveling into space wasn't such a new concept, reporters began to pay more attention to the space missions themselves, and the work the astronauts were doing. As Rhea Seddon later mentioned, "Everybody was pleased that there were no longer those sometimes silly questions." NASA's first six women astronauts could finally do what they were there for — they could simply be astronauts. One of the space shuttle's main aims was to launch and maintain satellites in Earth orbit. Perhaps the most famous of those was the Hubble Space Telescope — a spacecraft that Kathy Sullivan was directly involved in both deploying and maintaining.

As things calmed down, and the space shuttle became more established, Shannon Lucid explained to The Oklahoman, that she simply considered space travel her job, saying, "I really don't feel like I'm under any more pressure than anybody else that holds a job outside the home." For Lucid, ironically a very down-to-earth woman, the biggest challenge was disappointment when her first mission had to be delayed. Being an astronaut continued to be an extremely public job though, and NASA's astronauts still routinely went on post-flight press tours after returning to Earth. While usually routine question-and-answer sessions, these occasionally posed problems, such as when Lucid was given an unwanted invitation to travel to Saudi Arabia.

Working with Russia

NASA's astronaut class of '78 began traveling into space during the 1980s, in the final decade of the Soviet Union. When the U.S.S.R. was dissolved in 1991, it left NASA with the chance to work together with the newly formed Russia Space Agency (RSA), which would later become Roscosmos. Shannon Lucid had been the last of NASA's first six women astronauts to be assigned to a space shuttle mission, but with the new alliance between the American and Russian space agencies, she'd have the chance to take a big step that the others did not.

When Lucid made the decision to spend time on the Mir space station, a lot was still uncertain. As she explained to the NASA Shuttle-Mir Oral History Project, even as she was on her way to Russia for training, she didn't even know if she'd be able to actually fly at all. She was there purely on the chance that she might. Working with the Russians was still not a popular choice among NASA's astronauts, and when Lucid agreed to leave for Russia, she was the only volunteer. While the training wasn't easy, with the RSA running things very differently to NASA, Lucid's crewmates evidently made all the difference to her experience. Affectionately referring to them as "Yuri and Yuri," she mentions how they were "absolutely fantastic to work with," explaining how, "It was just a very good experience, I think, for all of us."

The legacy of the six

NASA's first six women astronauts made a permanent mark on the American space program. Tragically though, as of 2023, their number is now down to just four after the Challenger disaster tragically killed Judy Resnik, and the death of Sally Ride in 2012. The world of science, engineering, and space travel is very different now from what it was back in 1978, and it's thanks in no small part to the trailblazing done by this small group of pioneering women. In a Q&A session hosted by Houston Space Center, Anna Fisher notes that her biggest impact was in planning the construction and operation of the International Space Station while encouraging and mentoring young women working in science. Rhea Seddon also mentions the importance that they served, and still serve, as role models for new generations of astronauts.

In the same session, Shannon Lucid recalls women of her own age approaching her teary-eyed, so they could say how much it meant seeing her and the others working as astronauts. It's easy to forget how, not so long ago, any kind of career was out of reach for most women. Lucid mentioned similar points in a public talk at the 2009 Women in Science Conference (via The Oklahoman). Reflecting on how different the world now is, she gave the sage advice, "It's very important to encourage students to study and to be enthused about a wide range of things because the future is rapidly changing."