What Do The Terms 'Modernism' And 'Postmodernism' Actually Mean?

By now, terms like "modernism" or "postmodernism" have floated through popular culture enough that the reader has likely heard them. Most often the terms are used to describe a movie, book, or piece of art, or hurled as an insult between two people locked in a sociopolitical debate. The meaning and importance of these terms often get lost in use and shift with the trends and interpretations of the day. But for those wondering why, for instance, some people might feel disgust and not sentimentality when watching black-and-white footage of 1950's daily life, or why others praise the artistry of a gold-painted toilet, or why films seem increasingly ironic in tone and less sincere, then we can look directly to the immense cultural gap between modernist and postmodernist eras.

Overall, as The Living Philosophy outlines, the terms "modernism" and "postmodernism" refer to periods of history, with the former leading up to World Wars I and II in the first half of the 20th century, and the latter being everything since the 1960s, roughly. Also, post-modernism is often described as a reaction to modernism in the same way that a "post-war period" can't exist without a war. The modernist period was full of optimism and grand visions of the future, and the belief in human progress and enlightenment. But come the early 20th century such promises stood unfulfilled, and technological prowess usurped spiritual fulfillment. And so, postmodernist society turned to subversiveness, cynicism, and irony to make sense of the world.

Severed from the old world

There's no clean, textbook separation between modernist and postmodernist time periods. Nobody sat down on a Tuesday in 1961 and said, "Ok, people. I just checked the calendar. We're in the postmodern era now." Terms like "modernism" and "postmodernism" were created after the fact to describe things that had already happened, or were underway. This means that there's not only a bit of flexibility in our timeline, there's decades worth of time of overlapping time, and a lack of distinctiveness regarding in-between eras. This should make sense because society changes along with its generations, who learn, adopt values, and have children of their own.

Case in point: Each and every human society has been "modern" simply because it's existed at the apex of history. But as The Living Philosophy explains, the 6th century saw the first written use of the term "modern" refer to a crumbled Europe following the fall of the western half of the Roman Empire in 476 C.E. "Modern" was therefore severed from classical, and set the stage for the upcoming, fragmented medieval world. Medieval (476 C.E. to 14th century) bled into Renaissance (14th to 17th century) and then Enlightenment (1685 to 1815 C.E.), which segued to the Industrial Revolution (about 1760 to 1914, the onset of World War I). Hopes and expectations for the future grew this entire time, along with scientific knowledge, artistic hindsight, and an evolving sociopolitical sense. But come World Wars I and II, all of that radiant hope died.

The hopes of the Enlightenment

While modernism can encompass everything from the 6th century to the beginning of the 20th century, the heart of modernism lives in Enlightenment Europe from the late 17th century to the early 19th century, of which countries like the United States and its "liberty, freedom, and the pursuit of happiness" ideal is an offspring. This doesn't mean that scientific, philosophical, and political evolution didn't have detractors, or that everything was smooth along the way, or even perfect as a result. It's simply that the Western world started to cohere into a singular, grand vision of where the future could go: Humans were capable of beauty, change, and understanding, and society was improvable with enough knowledge and effort.

And so, as the British Library outlines, England cast its Bill of Rights in 1689 to limit the tyranny of government and advocate for the kind of civil rights that came to typify the future development of democratic institutions and personal liberties. Meanwhile, philosophers like Rene Descartes, David Hume, and Immanuel Kant bent themselves towards understanding human nature and perception, as Big Think explains. People like Isaac Newton showed that the world was a predictable, knowable thing that could be approached scientifically, while folks like John Locke and Thomas Hobbes advocated what we now call "rule of law" and a separation of church and state, per the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. All in all, there was no reason to assume that anything but upward-moving progress toward an earthly paradise awaited.

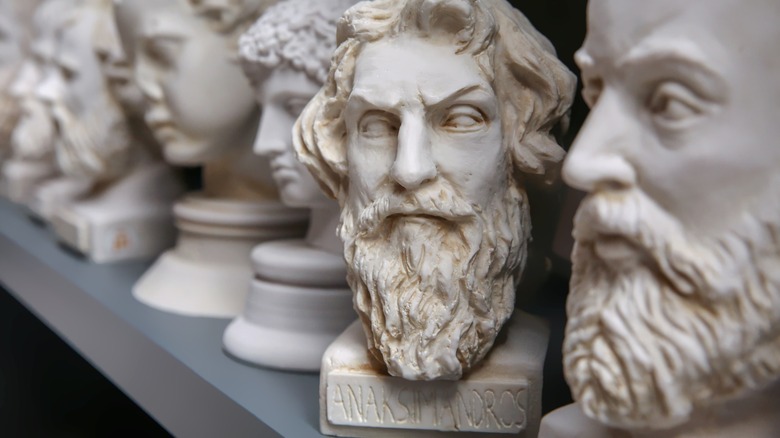

[Featured image by Mr. De Voltaire via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled]

A fractured promise

The Enlightenment wasn't a conflict-free utopia, but its conflicts were seen as symptomatic of growth. The Napoleon Bonaparte-overthrowing French Revolution (1789 to 1790) was bloody and horrific but uprooted oppressive monarchical institutions. The West's abolishment of slavery, starting with England in 1807, took decades of untold effort and strife, but was worth any price. Come the 20th century, technology lengthened life spans, lowered mortality rates, developed groundbreaking medicines, and created an overall higher quality of life than ever before in human history, as sites like Open Access Government detail.

But in the end, all this progress led to the "The Great War," as it was called. World War I was not merely the straw that broke the camel's back, but the anvil. All the knowledge and technology accumulated by humanity for hundreds of years was put to use not in the application of peace, justice, or enlightenment, but to shatter and detonate human bodies. Only a single generation after World War I ended in 1918, World War II engulfed the globe. World War II ended with the defeat of Nazi Germany in 1945 but left disfiguring societal scars and two dropped atomic bombs. No longer could humanity look around and think of sweetness and light. By the next generation, 1960s counterculture sought to upend all of modernity's fanciful visions by rewriting the script, so to speak. So began the decades-long flip to something less naive and steeped in the only psychological recourse possible: subversiveness, irony, and cynicism.

Subversiveness, irony, and cynicism

It should make sense: Sincerity, openness, and optimism leave a person vulnerable to pain and betrayal. Wry worldliness is a common pretention of those wishing to appear too tough to dupe or harm and entails an intellectualization capable of washing away the past by deconstructing it to atoms. This is postmodernism in a simplistic, overall nutshell.

French philosopher Michel Foucault often gets cited as identifying and defining the 20th-century's post-modern "attitude," as The Living Philosophy outlines. As Masterclass overviews, his work and others' gave way to subsequent schools of academic thought that treat the past through different lenses in an attempt to understand the present, including postcolonialism, feminist theory, queer theory, and most topically, critical race theory.

Artistic and architectural movements often stand at the forefront of such societal change and reflect the moment better than anything else. The shift from expressionism to dadaism to surrealism, etc., perfectly portrays the evolution from modernism to postmodernism through the early to mid-20th centuries, as The Collector illustrates. This is how we get contemporary pieces of art like bananas taped to walls, which chiefly exist to critique and defy the standards of the past, and even deconstruct "the idea" of art, per The Collector. Such attitudes can be useful if directed constructively towards institutions of power. But pushed to the extreme, postmodernism means endless fragmented voices crying without cohesion, demanding attention, each believing that it, itself, holds one, single truth, when in reality it's all voices together that compose truth.

A metamodernist future?

At present, even with brief outlines like in this article, terms like "modernism" and "postmodernism" remain largely misunderstood, in part because the postmodernist era is inherently self-aware, trend-bucking, and suspicious of final definitions. The Conversation describes this conundrum well, citing pop art like "The Simpsons" and a gaudy, gold statue of Michael Jackson and Bubbles the chimp. Prominent among the article's examples is "intertextuality" in contemporary culture, a term used to describe how the meaning of art exists in the interaction between the art and viewer, rather than being dictated from the top down. But even though art perfectly exemplifies postmodernism, its principles engage with every single aspect of modern life: politics and related movements, views on relationships and the family, outlooks on work and careers, economics and consumerism, down to fundamental definitions of human morality and value.

While some might take discussions of modernism vs. postmodernism as mere pedantry, they help us understand why, for example, some folks believe Earth is flat, or that humanity isn't worth saving in the face of climate change. If everything exists to be deconstructed, then nothing can be agreed on as true. This is why some have pointed to "metamodernism" as a solution, which as Notes on Metamodernism describes as unifying optimism with a lack of naivety, i.e., the modern with the postmodern. Irony still has a place here — not to mock or devalue, but to engender sympathy and earnestness. Such a solution might just be what contemporary society needs.