The Most Bizarre Things No One Ever Told You About The Lincoln Assassination

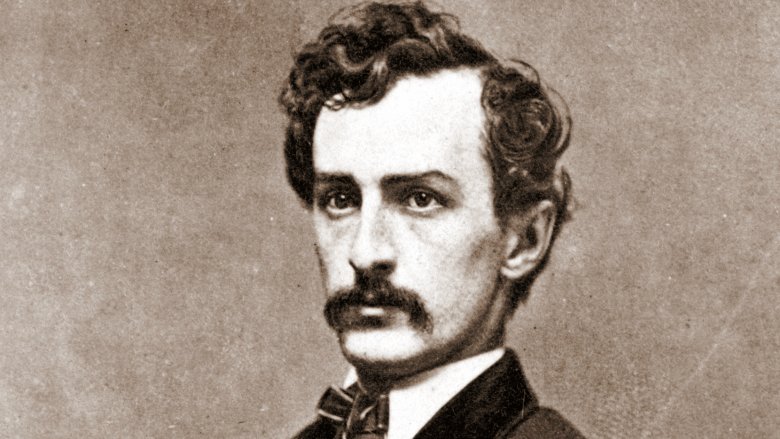

In 1862, actor John Wilkes Booth wowed crowds with his portrayal of historical villain Richard III. While explaining how he could play such a despicable character so convincingly, Booth remarked, "I am determined to be a villain." Truer words had never been spoken. On April 14, 1865, John Wilkes Booth became the darkest star ever to perform on the national stage.

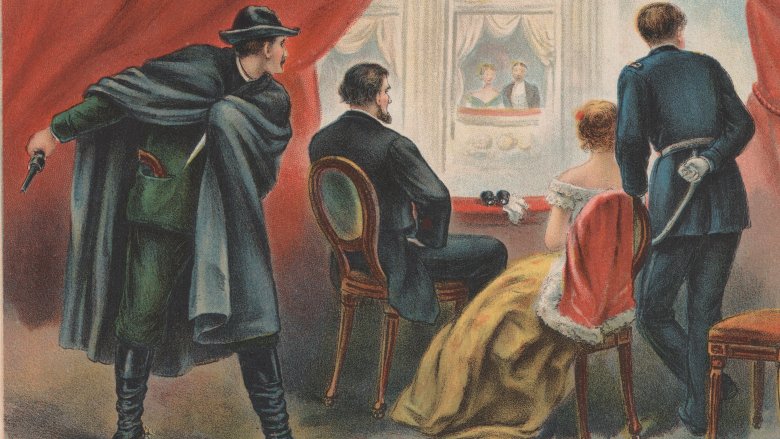

The scene played out at Ford's Theater in the nation's capital. As President Abraham Lincoln watched a production of Our American Cousin, Booth entered the president's box. When the play reached a scene guaranteed to draw big laughs, Booth drew his pistol and shot Lincoln in the back of the head. Before fleeing on horseback, the actor literally broke a leg leaping onto the stage and shouted, "Sic semper tyrannis! (Thus always to tyrants!) The South is avenged!" Lincoln died the following morning and Booth was shot dead in a burning barn.

The timing was almost as awful as the act itself. The Civil War had essentially ended five days before Booth struck, slaves had been emancipated, and now the country was reeling from its first-ever presidential assassination. Incredibly, there's even more to the story. The plot thickens with creepy coincidences, ironic outcomes, and details that get weirder as you dig deeper. Here are the most bizarre things no one ever told you about Lincoln's assassination.

John Wilkes Booth's father threatened to assassinate a previous president

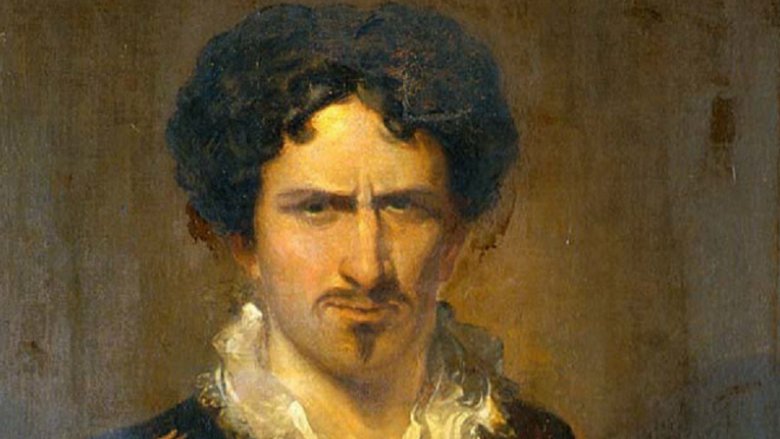

What are the odds that a man named after one of the most notorious assassins of all time would threaten to assassinate a head of state and then sire a son who later becomes one of the other most notorious assassins of all time? If you're Junius Brutus Booth, the chances are 100 percent. "Hailed as the greatest Shakespearean player of his day," according to the Chicago Tribune, Junius Brutus Booth shared two-thirds of his name with Marcus Junius Brutus, a.k.a. the dude who helped stab Julius Caesar to death.

Evidently intent on living up to his name, Junius Brutus sent a death threat to President Andrew Jackson in 1835. For some reason he wanted the president to pardon a pair of pirates that had been sentenced to death. Junius Brutus didn't mince words but he threatened to mince Jackson, writing, "I will cut your throat whilst you are sleeping."

Earlier that same year, a crazed attacker (who surprisingly wasn't Junius Brutus) tried and failed twice to shoot Jackson in what was the first known instance of an attempted presidential assassination. Three years after Junius Brutus's threat, John Wilkes Booth was born. In another 27 years, Booth would become the first person to assassinate a U.S. president. According to author Barry Strauss, that wasn't simply a coincidence. John Wilkes Booth was allegedly obsessed with Brutus the assassin and even portrayed him onstage several months before murdering Lincoln.

Lincoln saw Booth perform at Ford's Theater the same year construction of his funeral train began

When the time came for George H.W. Bush to be laid to rest at his presidential library, the 41st president traveled there by train, slowly chugging along so that crowds could pay their respects. At the late president's request, "the locomotive was painted to resemble Air Force One." When Abraham Lincoln, who's credited with popularizing the presidential funeral train tradition, made his posthumous journey to the grave, the train he boarded actually was his "Air Force One." Not by design, though, because Lincoln refused to be caught alive on that thing.

Construction of what would become Lincoln's funeral train began in 1863, per Atlas Obscura. That same year, the president watched his future assassin, John Wilkes Booth, perform at Ford's Theater, where Booth would shoot him two years later. The actor could scarcely hide his contempt, according to Fords.org, and apparently glared at Lincoln when his lines contained threats. The same year that Booth assassinated Lincoln, construction of the train was completed.

The U.S. Military Railroad built the locomotive to transport the president around the country like an old-timey Air Force One, but Lincoln deemed it too expensive in light of the Civil War. In fact, he refused to view it. Eventually, Lincoln relented and scheduled an appointment to see the train. The date of the appointment: April 15, 1865, the day he died. The train was instead used to take the belated president on a two-week postmortem tour of the country.

Booth admired (and might have emulated) an abolitionist

John Wilkes Booth may have hated Abraham Lincoln more than most people have ever loved anyone. Considering how acrimonious American politics can get when the country's not at war, that's not exactly shocking. However, it's downright jaw-dropping that Booth harbored a deep admiration for passionate abolitionist John Brown. Brown orchestrated a bloody raid in Harpers Ferry, West Virginia (which was then Virginia) in 1859 with the hope of inciting a slave revolt that would topple slavery altogether. The assault played a major part in igniting the Civil War.

Booth was firmly on Team Slavery and claimed Lincoln was "made the tool of the North to crush out, or try to crush out slavery." So you might expect that he would detest Brown, who made it his mission in life to crush out slavery. Yet the future assassin had a starkly different opinion: "John Brown was a man inspired, the grandest character of this century!" Booth respected him so much that he bailed on an acting gig to attend Brown's execution.

The reason Booth regarded Brown so highly was that he gave his life fighting for a "higher ideal" (Brown believed God chose him to lead a mass slave uprising). However, Booth called Lincoln "unfit to stand with that rugged hero" because he saw the president as power-hungry, dishonest, and "a disgrace to the seat he holds." When Booth killed Lincoln, he, too, felt that he was guided by a higher ideal.

The whole thing might have been a failed Confederate plot

It's no secret that Booth wasn't the only man with evil intentions on April 14, 1865. As History elaborated, his buddies George Atzerodt and Lewis Powell were supposed to snuff out the vice president and secretary of state. Prior to that, the treasonous trio and a fourth man, David Herod, wanted to kidnap Lincoln. And before that, Booth discussed abducting the president with Samuel Arnold, Michael O'Laughlin, and John Surratt. But even with this sizable cast of conspirators, it's generally accepted that Booth pursued Lincoln because he loved the South and was loonier than a toon.

In 1985 a retired CIA officer, a Department of Defense analyst, and a former Department of Labor official put forth an alternative account. Drawing from contextual evidence and a series of unearthed documents, they concluded that Booth was recruited to kidnap or kill Lincoln in a last-ditch effort to force at least a draw once the Civil War seemed unwinnable for the South.

Obviously, the surrender of Robert E. Lee rendered this mission pointless, but it's not like Lee could have emailed Booth about aborting the mission. The idea isn't without flaws, like the fact that Booth was an actor who lacked military training. However, the researchers cogently showed that the Confederacy was extremely fond of covert operations. Furthermore, Booth's main henchman and co-conspirator, John Surratt, was a card-carrying Confederate spy.

Booth and Lincoln's bodyguard drank at the same saloon before the shooting

Nowadays, a president probably can't blow their nose without the Secret Service frisking the tissue for weapons first. It's not unheard of for agents to follow a POTUS into hotel bathrooms, so it's utterly puzzling that President Lincoln's designated protector wasn't even in the theater when Booth pulled the trigger.

The man who was supposed to stand between Lincoln and bullets was John Parker, whom Smithsonian described as "an unlikely candidate to guard a president — or anyone for that matter." Formerly a carpenter, Parker was hired as one of D.C.'s first ever cops. And holy moly, he sucked. His lengthy history of incompetence included drinking on the job and sleeping on a streetcar. Parker's excuse for snoozing: he heard ducks quacking on the streetcar and decided to investigate.

Somehow that guy got picked to protect a towering historical figure. It's worth noting that presidents were pretty lightly guarded prior to 1902, and since John Wilkes Booth was a renowned actor, it's possible that he wouldn't have registered as a threat. But even by terrible standards Parker was a terrible guard, which he proved when he left Ford's theater to go drinking at the Star Saloon, the same saloon John Wilkes Booth visited before assassinating the president. Unbelievably, despite tossing back drinks while the president got shot, Parker worked at the White House another three years before getting canned for sleeping yet again.

Lincoln went unprotected because his bodyguard went drinking; Johnson was protected because his assassin was drinking

Anyone who's awoken from a bender with a new tattoo or unexpected spouse knows alcohol can change your life. But in 1865, it helped change history. Lincoln was left unprotected when his feckless bodyguard left Ford's Theater to have drinks at the saloon next door. Booth, meanwhile, drank at the same saloon to muster up the guts to kill the conveniently unguarded president.

Then there was Vice President Andrew Johnson, one of the other targets of the night. Had things gone entirely as planned, co-conspirator George Atzerodt would have killed Johnson while Booth was assassinating Lincoln, and Lewis Powell would have murdered Secretary of State William Seward. However, as Newsweek detailed, Powell ambushed Seward with a Bowie knife but failed to finish the job after multiple people (including Seward's children) intervened, and Atzarodt never even got started.

While President Lincoln had a useless boozehound for a bodyguard, the man chosen to assassinate Vice President Johnson was an equally useless boozehound. According to the U.S. National Archives, Atzerodt got wasted at the bar of a hotel where Johnson was staying. He multitasked by asking extremely suspicious questions and not bothering to conceal his real name. He also didn't bother attacking Johnson, opting instead to meander drunkenly around D.C.

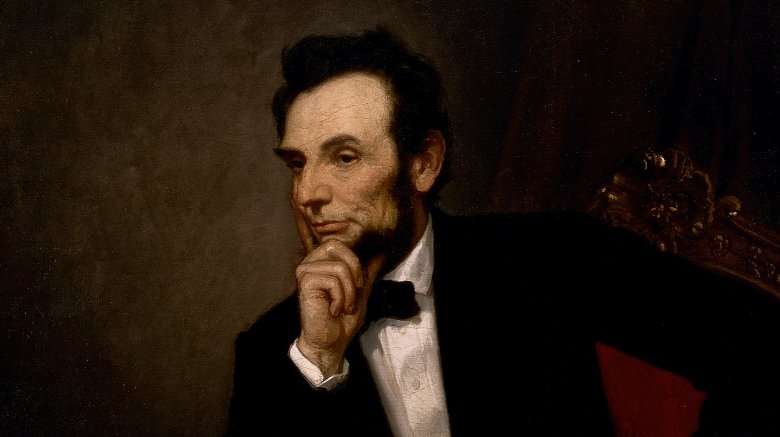

Lincoln was replaced by his political evil twin

President Andrew Johnson was, to put it kindly, a sentient disaster masquerading as a person. Okay, maybe he wasn't all bad, but he was bad in all the ways America needed him not to be after the Civil War. Whereas Lincoln was a deep thinker, conciliator, and emancipator of slaves, according to history professor Elizabeth Varon, Johnson "is viewed to have been a rigid, dictatorial racist who was unable to compromise or to accept a political reality at odds with his own ideas."

The weird thing is that choosing Johnson as a running mate in the 1864 election was a shrewd political maneuver on Lincoln's part. As Professor Varon explained, "Johnson was the most prominent 'War Democrat' in the nation" and enormously popular among small farmers and villagers throughout the Union. However, after Lincoln's assassination, Johnson worsened the nation's wounds instead of healing them. Whereas Lincoln intended to safeguard the freedom of liberated slaves, Johnson vehemently opposed giving them civil rights, curtailed efforts to give them land, and approved the passage of the "Black Codes," which unofficially instituted slavery. Johnson also resented the whole checks and balances thing, and defied Congress so deliberately that he became the first president ever to be impeached.

The other historic death

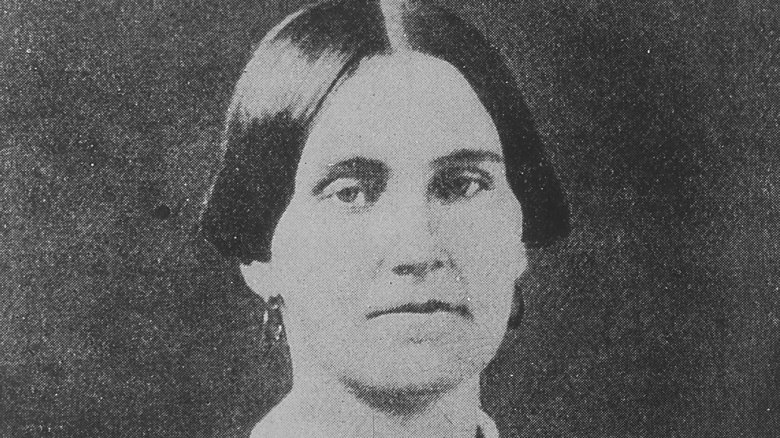

Few deaths impacted history more drastically than Lincoln's. It completely redrew the blueprint of Reconstruction and led to the nation's first presidential impeachment. Oddly, it also resulted in another historic death: that of the first woman ever executed by the federal government. That woman was Mary Surratt, an accused Booth collaborator and the mother of Booth's most trusted henchman. Her story was even the subject of the 2010 film The Conspirator, in which she was played by Robin Wright.

A former slave-owner from Maryland, Mary lost her farm in a fire allegedly set by a runaway slave, according to Time. After relocating to D.C., she opened a boardinghouse, where Booth and friends plotted against the president. Instrumental in helping Booth find partners in crime was Mary's son, John Surratt. John worked directly for the Confederacy as a courier and spy, according to History. In the aftermath of the assassination, John fled the country and Mary stood trial before a military tribunal for allegedly abetting the murder.

Trying a civilian like a soldier isn't the norm, but it wasn't a normal situation. Mary pled total ignorance, but multiple witnesses contradicted her. Booth accomplice Lewis Powell, however, vouched for Surratt, but the words of a would-be assassin probably didn't hold much sway. Historians aren't sure what Surratt knew, but her tribunal decided she deserved to die.

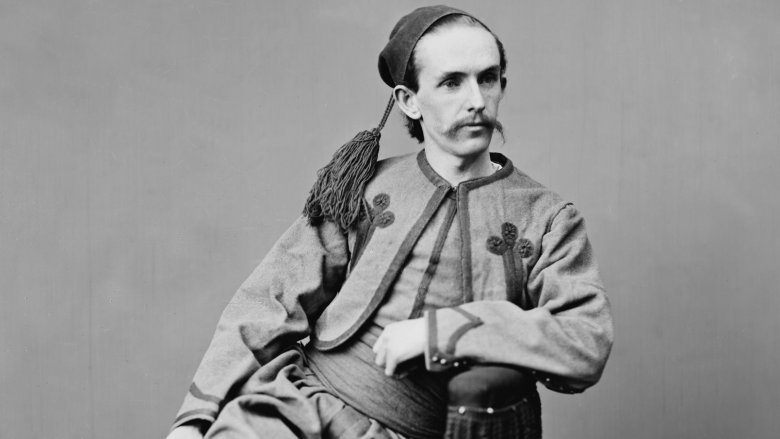

John Surratt's surreal game of cat and mouse

Historians are left to ponder whether Marry Surratt, the first woman to be put to death by the U.S. government, got a raw deal in the fallout from the Lincoln assassination. But there's zero doubt that her son John, a verified Confederate spy, got away with figurative and possibly literal murder. For two years he was the most wanted fugitive on the planet.

While most of the suspects tied to Booth were rapidly rounded up and Booth quickly ate a bullet, Surratt skedaddled. Per the Washington Post, he was partly aided by his eerie twin-like resemblance to a Confederate soldier named John, who spent three months in the slammer. The real John, meanwhile, wore disguises and absconded to Canada.

A global game of cat and mouse followed as Surratt went country-hopping across Europe. At one point he went to Italy, assumed the name Giovanni Watson, and joined the pope's personal army. At one point, he was apprehended but escaped prison by leaping into a heap of human poop. He was finally nabbed in Egypt. Weirdly, the treatment he received back in the States mirrored his mother's. While Mary Surratt the civilian was tried by a military tribunal, John the spy was judged by a civilian jury. And while Mary died by hanging, John benefited from a hung jury and went free.

Samuel Mudd's prison road to redemption

Dr. Samuel Mudd's reputation became dirtier than his surname after his connection to John Wilkes Booth came to light. A surgeon during the Civil War, Mudd treated Booth for a broken leg the morning after he murdered Lincoln, according to Smithsonian. That looks pretty incriminating, even for a doctor, and Mudd was done for once it was discovered that he met with Booth before the shooting as well.

Mudd steadfastly denied conspiring to kill he president, but was condemned to spend the rest of his days at Fort Jefferson, a Civil War fortress that had been converted into a federal prison. Joining him were three Confederate soldiers who had hammered out a plan with Booth to abduct the president (which they never attempted) plus a Ford's Theater employee who helped Booth flee. It was about as cozy as hell on a humid day. Bedbugs and fleas abounded, and meals included quickly rotting meat and bread allegedly made from "flour, bugs, sticks and dirt."

The color of hell was yellow, thanks to the yellow fever-ridden mosquitoes that plagued Fort Jefferson. In 1867, an outbreak threatened to kill hundreds of people. The inmates and staff of Fort Jefferson were lucky Mudd was there to begrudgingly ran the prison hospital. Thanks to his tireless efforts, only 38 of the 270 sufferers died. Among the survivors was a lieutenant who campaigned to have the doctor released. In 1869, President Grant pardoned Mudd.