What Were Funerals Like In Colonial America?

On the surface, funerals seem timeless. When a person dies in a community, some number of people gather to manage the body, commemorate the deceased's life, and mourn together. The details may change from generation to generation, but the basic format remains familiar.

But those details can make a serious difference. If you were to attend a funeral in colonial America, for instance, you would likely encounter practices that would seem unfamiliar to you. We're not just talking about a minister standing in front of everyone wearing a wig (or denouncing the fashionable headgear), either. Puritan services from the early years of American colonialism could be nearly silent affairs, while other people in the community might find themselves subject to segregation, sumptuary laws, and a flood of commemorative gloves.

Taking a closer look at how funerals happened during this era gives us a surprising level of insight into colonial society in general, from its start in the early 17th century to the waning decades of the 18th century. Here's what it may have been like to witness a funeral in the American colonies.

Funerals often had to be arranged quickly

In an era before embalming or even consistent refrigeration, funerals had to get moving fairly quickly. Before the American Civil War of the 1860s, most deceased Americans would have been subject to a fairly fast-paced progression of washing, viewing by family and community members, and a burial within a week or so. Perhaps if someone had died during an especially cold spell, family and friends might have a few extra days, but few of the living seemed interested in lingering over the process.

If a community was in the middle of an especially stressful period, funerals might be truncated or even discarded altogether. In colonial Virginia, the settlers at Jamestown faced a stark reality during the winter of 1609-1610, in what widely became known as the Starving Time. Typically, the dead of this period were buried in simple shrouds, sometimes in coffins and nearly always in purpose-dug graves. But burials from that winter show some people were interred in a hurry, still wearing their clothes or awkwardly crammed into too-small graves. Survivors wrote that some of the dead were even exhumed to be eaten, as cut marks on at least one skeleton make clear.

Victims of a March 1622 tribal uprising at the Martin's Hundred settlement in Virginia were also apparently hastily buried without coffins or shrouds. However, historical evidence indicates that they were at least placed in graves and given some degree of remembrance.

Early Puritan funerals were quiet affairs

Because so many early New England communities were downright frantic to avoid the barest whiff of Catholicism — they had, after all, traveled across an entire ocean to escape that sort of thing — Puritan funerals were largely silent. Early settlements in places like Ipswich, Massachusetts didn't brook remembrances like eulogies or sermons related to the deceased. After a procession to the graveyard, a few words may have been uttered at the burial, but that was about it. If someone was of sufficiently high standing, a sermon might be preached at some point after their death, but it would have been folded into a regular service lest anyone think the deceased was too special.

However, even the seemingly immovable Puritans changed as time went on. Perhaps the silences started to get awkward or mourners felt that a sober, close-lipped service wasn't good enough for their loved one. As the 17th century came to a close, people indulged more in remembrances, eulogies, special sermons, and even sometimes embalmed the dead to give everyone more time to mark the occasion of someone's passing.

Puritan funerals leaned into grim messaging

If you were a Puritan mourner looking for a bit of comfort at an early colonial funeral, you would have been better off looking elsewhere. English Puritan colonists had an uneasy relationship with the concepts of God, death, and the afterlife. Sure, they believed in an almighty deity and a heaven that held eternal bliss for its occupants. They also believed that most people went to eternal torment in hell after death. Moreover, they claimed that God had already decided who would go where before they had even been born, a Calvinist doctrine known as predestination. But no one knew for sure if they were one of the heaven-bound elect, so anxiety about sin and the afterlife was still rampant.

Funerals represented an obvious occasion for preachers to thunder on about the inherently sinful nature of humanity and leave everyone in the congregation fretting about one's own fate. Yet there would be no heartfelt eulogies focusing on the deceased. According to the strict Calvinist views of early American Puritans, no one but God could say for certain where the dead person's soul had ended up. Even prominent religious figures like minister Increase Mather went to their deathbeds wracked with anxiety over that very question. Those left behind at the funeral fared little better.

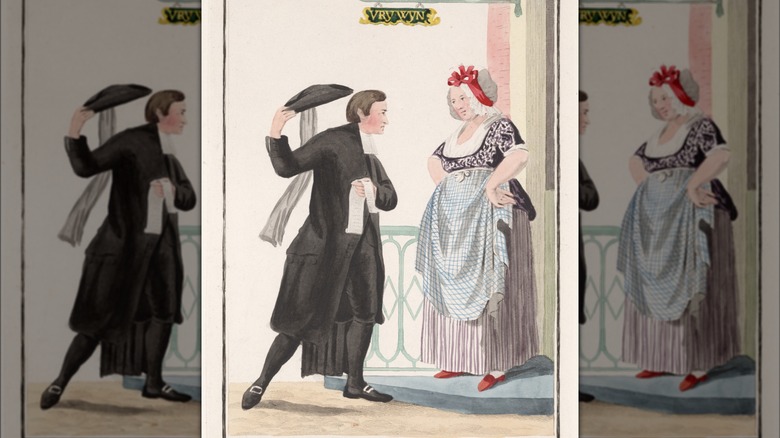

Dutch settlers might encounter a funeral inviter

Of course, Puritans weren't the only people who began to colonize North America, even if they might have wished that weren't the case. Over in what's now Albany, New York down to Delaware, the Dutch had put down roots beginning in the early years of the 17th century. Naturally, they brought many customs with them, including a funeral tradition that had a grim figure appearing occasionally on the doorstep.

The spectral personage was actually a messenger dressed all in black, known as an aanspreker. His job was to dress up, go from home to home, and formally invite members of a household to a funeral. Given that you simply did not attend a funeral without being asked first (at least unless you wanted to completely tank your social standing), the aanspreker was a vital component of funerals and mourning in New Amsterdam. Though they started off as general workers who also did most of the grave digging and burial ground maintenance, they eventually became local minor officials who could command a decent fee for hoofing it out to far-flung homes while wearing formal wear. And, of course, if one aanspreker was good, why not two or even more? For especially wealthy dead folks in later decades of the colonial period, a whole team of the inviters might parade through town, ostentatiously mourning and delivering the news.

A coffin might be carried in a relay

Today, funeral processions might include a casket carried by people, but they typically only make a short walk from the service to a waiting hearse. But the early colonizers of New England didn't have a motorized car idling at the ready. They didn't even necessarily have a horse and wagon. Instead, Puritans were more likely to carry the coffin by hand from the service site to the graveyard. Sometimes, a double set of pallbearers might be used: a group of younger men to do the heavy lifting, while elders might walk alongside carrying an edge of the cloth pall draped over the coffin.

Depending on the community, this could be quite a way to walk even if one wasn't helping carry a body. If it was a long enough journey, the pallbearers might switch out with a second team halfway. Sometimes, people might find a spot to set down the deceased while they rested before taking up the coffin again.

Some colonial dead lie beneath intricate headstones

Initially, the dead of colonial America were laid beneath simple wooden markers or, as some historians have guessed, their graves might be marked by nothing at all. It was in line with the unadorned Puritan aesthetic, but eventually, even many Puritans had enough of the hardline way of things. Gradually, grave markers in the colonies began to get more spendy, transforming from rough-hewn slabs of stone to intricate monuments crafted by master stone carvers. They also tended to include stark reminders of mortality, like the winged skull commonly known as a death's head (sometimes also shown with crossed bones).

Soon, other imagery began to join the mix, including hourglasses, coffins, and inscriptions that went from a simple name and set of dates to reminders of the reader's looming death (including the ever-popular "memento mori"). As time went on, later monuments softened the message and got downright flowery, with poetic epitaphs and more comforting images of willows, urns, and baby-faced cherubs.

As the North American colonies became more prosperous, it was possible for skilled stone carvers to build a serious reputation. Many developed a unique style that researchers have been able to link to names and workshops throughout New England and beyond.

American Indian tribes had unique burial customs

Of course, Europeans weren't the only people who lived in the Americas during the colonial period. Puritans and others who stepped off transatlantic sailing ships were setting foot into territory that was already occupied by a vast array of indigenous tribes. And, just like practically anyone else on the planet, American Indians of the era had their own unique funeral practices. In 1588, Thomas Hariot wrote that the indigenous people of Roanoke, Virginia believed in a heavenly afterlife for the good and a dark, grim, and burning pit set aside for the bad. He also mentioned that high-ranking members of the tribe received special burials, much like Theodor de Bry noted in 1590 when he created an illustration of a burial temple set aside for the elite of the Algonquin tribe.

Nearly 50 years later, Thomas Morton chronicled some of the funeral practices of New England tribes. Though he failed to name them (they were likely the Wampanoag people), Morton did note that the people who lived near Plymouth, Massachusetts reinforced the graves of elite tribal members with wooden planks, painting their faces black in mourning, and once avoided even talking about the dead (though the social taboo softened after coming into contact with European colonists). They also marked higher-class burial spots with a special cloth. When Pilgrim colonists removed the cloth over a chieftain's mother's grave, a fight ensued over the defacement of a burial.

Funerals got elaborate

Though it may seem like the highly religious and conservative Puritans dominated the colonial period, not everyone was on board. There were the Pilgrims, who had arrived about a decade earlier than the Puritans and Quakers, another group of religious dissenters who butted heads with the Puritans. There was even a small population of Catholic settlers in the British colonies, as well as the indigenous people and enslaved Africans who had their own funeral customs. It's no wonder that colonial funerals soon began to move on from the unadorned ceremonies favored by Puritans.

By 1717, the death of Waitstill Winthrop, grandson of Massachusetts governor John Winthrop, was occasion for much pomp. His funeral procession included drummers, military personnel with shiny new weapons, and expensive gifts. Waitstill's funeral cost more than 600 pounds (one-fifth of his estate) and exceeded the annual tax revenue of pretty much anywhere in the colonies outside of Boston. As with other upper-class funerals, family members of Winthrop may have sported mourning clothes of black cloth, while the dead might be conveyed to the graveyard now by carriage, which could be outfitted with a team of horses specially dressed for the occasion in black.

Funerals were also getting louder. Besides drums, the occasions might also include trumpeting, the tolling of bells, and the firing of guns. Even John Winthrop's funeral was reportedly marked by rounds fired over his grave, to the tune of a full barrel and a half of gunpowder.

Puritans tried to ban overly elaborate customs

As colonial funerals began to feature more and more details, hardline officials began to get concerned. It must have seemed as if their vision of a city on a hill (famously referenced by big-name Puritan John Winthrop in "A Modell of Christian Charity") was crumbling before their eyes. In reaction to the changes, some enacted new rules to curb the funeral pomp. These included limits on bell tolling, which was justified as a loud, head-ringing bother for everyone in the community.

It wasn't just that these increasingly fancy funerals were a bit too Catholic or continental, either. Some colonial families were even courting bankruptcy by engaging in overly elaborate funerals, especially widows who were left with no breadwinner and a family that still needed food and shelter. To that end, by the middle of the 18th century in many colonial settlements, officials began to enact sumptuary laws. These limited how much mourners could be charged for funeral services, capped prices for mourning wear, and penalized anyone who went overboard with the gifts and booze at the wake.

Funeral gloves became hot collectibles

It's understandable that grieving family and friends might want a remembrance of their lost loved one. While today we might look fondly at photographs or even claim a keepsake or two, colonial funeral attendees might expect something more. By the 18th century, those attending an upper-class funeral simply had to have gloves. Meant as a memorial keepsake, the gloves might have been paid for out of the deceased's estate and were typically handed out in a hierarchical fashion — the most important people, like close family, would get their pairs first. Sometimes, other attendees wouldn't get gloves, while others who couldn't make it to the service would still receive their pair or some other remembrance in the mail. Yet others got their gloves ahead of time as an invitation to the funeral.

These gloves might be cherished and passed down amongst family for quite a long time. They could have been a bit of a money-making opportunity for people like Boston minister Andrew Eliot, who received nearly 3,000 pairs of funeral gloves over his 32-year career and sold some during the latter half of the 18th century.

This wasn't merely an occasion for callow gift-grabbing, either. In The William and Mary Quarterly, Steven C. Bullock and Sheila McIntyre argue that this practice also helped to build and reinforce social networks in the colonies. In a world where social standing and community support were vital, spending extra on funeral gloves could be a surprisingly big deal.

Other gifts might also be given to mourners

Though gloves were a popular funeral souvenir during the 18th century, they weren't the only token that a mourner might receive. Rings were also a popular way of commemorating the dead and might include decorations of coffins and skulls or engraved lines such as "Death Parts United Hearts" or "Prepare for Death" (clearly, the Puritans were still around in one form or another). Minister Andrew Eliot, already struggling a bit with his massive funeral glove collection, also had so many funeral rings that he also sold them off over time. Diarist Samuel Sewall recorded a count of 57 funeral rings in his collection, while Salem doctor Samuel Buxton reportedly had a tankard full of not-so-lovingly collected rings (Eliot reportedly did much the same). Meanwhile, the moneybags Winthrop family handed out 60 pricey rings for Waitstill Winthrop's 1717 service.

It wasn't just a simple matter of digging some rings out of a bag and handing them out to mourners at the service, either. Quite a few diaries record people crowing over their achievement of snagging a ring. Families also had to think carefully about who got what kind of ring, and who might get offended if they didn't receive a sufficiently blinged-out bit of jewelry in line with their status. It all got to be so much that rings were among the gifts outlawed by a 1741 Massachusetts Provincial Enactment meant to curb the excessive funeral spending amongst the colonies' richer sorts.

Black colonial people had their own own funeral traditions

African people forcibly brought to the North American colonies to work as slaves first arrived in 1625 in New Amsterdam. By the time English settlers took over the colony and named it New York, a small community of free Black people had formed there, too.

The funerals of the enslaved were subject to tight regulations as the enslaver officials feared uprisings organized at social events such as these. Some communities limited the number of mourners who were allowed at funerals, while others required passes. In 1687 Virginia, the Northern Neck region even saw legislation that outlawed slave funerals entirely.

However, funeral traditions persisted well into the depths of 19th-century enslavement, indicating that earlier generations of enslaved people weren't about to let their traditions fall by the wayside. These included practices that can reasonably be linked back to African funeral traditions. According to David R. Roediger in The Massachusetts Review, this included the practice of allowing only a small subset of people to wash a body, while everyone else strictly avoided touching remains until after this step was completed.

Some individuals buried in what's now called the African Burial Ground in New York City were also found with coins, beads, and shells in their coffins, perhaps speaking to funeral traditions carried over from their ancestral homelands. Back in 1602, Pieter de Marees wrote that Akan-speaking people in what's now largely Ghana buried the dead with goods meant to help them in the next world.

Burial grounds were often segregated

Class can be one of the most obvious signs that mark some colonial dead from the rest. Even coffins differed according to status, as the richest could order fine stone or metal sarcophagi that contained well-made wood coffins. Meanwhile, the poorest family might only be able to provide a shroud and a rented coffin that would go back to the parish church.

Then, there was the matter of race. Enslaved and free Africans and their descendants might well expect to be buried in cemeteries segregated on the basis of race. In Newport, Rhode Island, that might have been a spot known as "God's Little Acre," which may well have the oldest grave markers for Africans in North America. These are especially notable as stone markers were costly, indicating that Black families in Newport had access to both the money and skilled Black stonemasons who were necessary to create the markers.

In New Amsterdam (eventually to become New York City), Black community members could be buried in what is now called the African Burial Ground, the earliest known Black cemetery in the nation, with burials dating from the 1630s to 1795. However, there are occasional exceptions to the rule. Crispus Attucks, a man of Black and indigenous heritage who was killed in the March 5, 1770 Boston Massacre, was laid to rest in Boston's Granary Burying Ground along with the likes of Samuel Adams, Paul Revere, and John Hancock.

Some were denied funerals altogether

Even the bare-bones Puritans needed a way to mourn the loss of a loved one and mark a major event in their communities. But not everyone was accorded a memorial or even a proper burial as the colonists saw it. For people who were believed to have violated some of the most closely held rules of a community, a simple grave would have offered too much respect. Instead, they were subject to what's sometimes called a deviant burial, in which normal burial practices are almost entirely ignored. In other societies, this might include ritualized violence enacted on a corpse, as when someone drove a stake into the remains of a suspected vampire or a person who died by suicide was buried at a crossroads and not a church-sanctioned graveyard.

In colonial America, the most notorious examples of deviant burials belong to the victims of the Salem witch trials. Though there is no official record of what happened to the people who were falsely accused of witchcraft and then hanged, they almost certainly would have been left somewhere near the execution site on the outskirts of town. No one would have seriously proposed burial in a sanctioned cemetery like the town's Charter Street Cemetery. But local legend has it that family members of at least three of the victims went to the spot under cover of darkness to exhume the bodies of their loved ones and give them a secret, but somewhat more proper burial elsewhere.

Food and drink were a big deal at funerals

By 1770, the average colonist was guzzling down about three and a half gallons of alcohol a year, roughly twice as much as Americans today. That typically came in the form of home-brewed beer or cider, locally distilled whiskey, or pricey imported rum. And, as some attendees of modern wakes already know, alcohol has long played a central role in American funeral customs.

Some colonial communities might have a pre-funeral wake with plenty of rum, followed by another boozy get-together after the burial was completed. Just about everyone would get some sort of alcohol at their funeral, whether it was a humble couple of gallons of cider at a poor person's service, or a presumably fully stocked bar at a minister's funeral (the bill was often even footed by the church).

Booze was often a pretty serious line item in a colonial funeral budget. One David Porter of Hartford, Connecticut, unfortunately drowned in 1678. Records of his funeral indicate that his attempted rescuers and those who recovered his body were given an extra helping of liquor, while members of the inquest received two quarts of wine and a gallon of cider. For the funeral proper, eight gallons and three-quarters of wine were set aside, as was a whole barrel of cider. The bill is almost entirely alcohol-based, with Porter's shroud and coffin tacked onto the very end as if they were afterthoughts (via "Customs and Fashions in Old New England").

Some homes draped almost everything in mourning black

While colonial mourners would go about procuring new sets of somber clothes — assuming they had the means to do so — they weren't the only ones getting dressed up for a funeral. Textiles would be just about everywhere, with black cloths sometimes draped over the pulpit where a minister would give his sermon and bits of black ribbon wrapped around all sorts of gear to give an appropriately gloomy aesthetic. A purpose-built bier meant to hold the coffin during a funeral was also draped in a dark fabric called a pall (or bier- or mort-cloth) that was sometimes owned by a large enough town.

Even homes could be wrapped in cloth to show that their occupants were in the depths of mourning. Around Hartford, Connecticut, mirrors, pictures, and various tchotchkes around presumably well-to-do homes were covered up in cloth on the occasion of a funeral. Some Philadelphians even reportedly went so far as to wrap their shutters in black cloth for up to a year. In 1759, the high-ranking family of military commander Sir William Pepperell was recorded as having wrapped just about everything in their house in dull, black fabric, including family portraits that were temporarily hidden from view.

Colonial mourners sometimes got literary

In stark contrast with old-school Puritan funerals where hardly a word was said, later colonial deaths pushed people to acts of poetry. Sometimes, these were appropriately somber tributes in verse form, while others took this time as an occasion for making puns and bits of doggerel that were shared amongst community members.

Others took the occasion to speak of the paradise awaiting some of the dead. Puritan poet John Danforth wrote after the 1710 death of 19-year-old Mary Gerrish that she was surely in heaven, but also that "had you Enjoy'd her longer,/The Bands of Love had Faster grown,/and Bands of Grief much stronger." Danforth's funeral verse for Gerrish was packed full of metaphor and sunny images of paradise, to be sure, but also came with a tinge of stern Puritanism lingering into the 18th century.

Sermons, which may have offered a more acceptable form of poetry for some, were also sometimes printed for later reference. Reportedly, they were sent out with black borders and a bare skull or another form of a death's head, in case any of the readers hadn't quite gotten the message at the start.

Where the dead were buried depended on location

In colonial America, just about everyone was buried. Alternative ways of dealing with the dead, like cremation, were still many decades away from being considered acceptable. But where, exactly, one might be buried was a subject that had much more room for variation. In the larger cities of the colonies, such as Boston, elites might be buried next to a major church or even beneath the floors of these sacred spaces. In St. Paul's Church in Eastchester, New York, minister Thomas Standard was buried directly beneath the church, a mark of honor that was hard-earned for an Anglican preacher who once butted heads with Puritan locals at the beginning of his career.

Smaller communities might have a common burial ground or churchyard associated with a house of worship. In Williamsburg, Virginia, free and enslaved Black people established the First Baptist Church in 1776. Besides worshiping there, parishioners also buried their dead nearby, as a modern excavation uncovered evidence of at least 63 burials next to the original church as of 2023. Meanwhile, some of the rural dead might be placed in small family plots located right on the farm, leaving the deceased resting fairly close to home in a quiet (and, eventually, sometimes forgotten) section of the property.

Gender was a factor in colonial funerals

For much of the colonial era, death was a domestic affair. Instead of hospitals, senior homes, or hospices, people more often died at home, leaving family members to manage the body and arrange for a funeral service. Who did what was often decided on the basis of gender.

Women were often tasked with caregiving. After someone's death, that meant cleaning and dressing the body, a duty that could include both immediate family and community members like neighbors and the local midwife. They would have also prepared clothes for the burial, including a loose, open-backed garment commonly called a shroud, as well as more common clothing items like stockings and soft shoes. In more urban areas, women might even work as quasi-professional layers out of the dead. Women would also typically be expected to take part in funeral processions and put together a meal and drinks for the living who attended services and wakes.

Meanwhile, men would have gotten to work crafting the coffin, a simple container that was often put together by a local carpenter or cabinet maker. While woodworking was very much a male-dominated field, so, too, was the religious side of things. From church caretakers known as sextons to the minister conducting the service, men would have taken on the public religious duties necessary at a funeral. They would have also taken on much of the physical labor, such as digging the grave and transporting the coffin from church to burying ground.

Later colonial funerals showed a dramatic shift in perspective

In contrast to earlier Puritan affairs that were all about getting listeners into a quivering state of anxiety over imminent hellfire, later colonial funerals were quite a bit cheerier, comparatively speaking. Funeral sermons gave ministers a chance to boost Christian doctrine by talking about the deceased's good example. As colony communities made it further into the 18th century, mourners were more likely to focus on comforting scenes of their loved ones in heaven. They, too, were more likely to expect to meet up again with their loved ones after death, as hellfire was less of a given and the Calvinist notion of predestination was less prevalent.

Graveyards soon reflected the change, too. Stark death's heads and bones carved into gravestones were steadily replaced by softer pictures like willows and classically-inspired urns. Meanwhile, the text carved on those stones began to more obviously reference souls, implying that something of the dead continued on in a happier afterlife, where they waited for their still-living family to join them one day.

Even Cotton Mather, the big-name Puritan minister who was entrenched in the old way of doing things, changed with the times. In his 1704 sermon for the funeral of Sarah Leveret of Boston, spoke of the deceased woman's "exemplary piety" and comforted mourners with a final image of her entering heaven where "God has there wiped all Tears from her Eyes. We must have them in Ours, till our Arrival thither after her."