The Most Disturbing Thing About The Spanish Inquisition Isn't What You Think

A ton of terrible things have been done in the name of religion, and when it comes to Christianity, the Inquisition is up there on any list. Even today, just the mention of the Spanish Inquisition is enough to bring up dark images of torture, executions, and demands for confession.

And that's what they were really after, says History. Inquisitors had the power and authority of the Vatican behind them, and their job was to track down heretics and punish them however they saw fit. The punishment depended on the crime and whether the suspected heretic admitted their transgressions, and could range from a pilgrimage and penance to a public flogging or execution.

The list of people in the Inquisition's sights is long: They targeted Jews, Muslims, and Cathars, along with scientists and others whose professional or personal beliefs and teachings didn't fall in line with Catholic rhetoric. Just how many people were executed is debated, with estimates ranging from just 1,200 into the millions.

So, what was the worst part about living through the Spanish Inquisition? Not what most people think.

Everyone expected the Spanish Inquisition

"Nobody expects the Spanish Inquisition! Our chief weapon is surprise!" The sketch is pretty famous, and it's a perfect example of Monty Python's ability to take some of the darkest parts in history, turn them on their head, and make them hilarious while actually teaching something. But in this case, their sketch became more popular than the truth, and it's probably one reason there's a belief that the Inquisition was a sort of shadowy entity that could show up any time in any place, then snatch away people they thought were heretics. That's pretty much the opposite of true.

Inquisitors would move from town to town, and Torquemada's official instruction booklet says the first thing they did was publicly announce they were there and designate a Sunday or an upcoming holiday as the day when all the faithful were to gather at the local church for a sermon. That sermon would be part Mass and part warning, where townsfolk would be instructed to come forward and admit heresy if they wanted leniency.

The next 30 or 40 days would be essentially a grace period. People could speak to inquisitors and confess under a guarantee "they shall not suffer death, imprisonment, or confiscation of their property." So the surprise nature of the Inquisition wasn't the worst part. It was when people didn't seek forgiveness that the problems started.

It wasn't the first time the Church did this garbage

The Spanish Inquisition really got started in 1478, when Pope Sixtus IV decided he'd had enough of sharing Spain with Jews, and particularly, Jews who publicly converted to Catholicism but continued to practice their true faith in secret. They were called Marranos, and the Vatican claimed they were the real threat (via Britannica).

But it wasn't the first Inquisition to be formally organized and supported by the Vatican. In 1227, Pope Gregory IX appointed a formal board of inquisitors to root out heresy in Florence, and within four years, he had drafted a formal set of rules based on ancient Roman law. And it was out of control. The head inquisitor in France was so enthusiastic he burned 180 people at the stake in a single day. The Dominicans were put in charge of this medieval Inquisition, and they hunted down a pretty long list of people that included the Cathari and Waldenses (both heretical offshoots of Catholicism), diviners, witches, and blasphemers (via Rice University).

There was a weird reason behind Gregory's legitimization of the Inquisition, too. He was sick of ordinary people taking out these groups without a trial, so he formalized it. It's also worth noting that Inquisitions in some places were little more than mob violence with authority, as not everyone thought they needed to answer to the Pope.

How the Inquisition created a figure still worshiped today

The world's Jewish population has been accused of a ton of horrible things, and one of the actions touted by the Inquisition was blood libel. That's the batty idea that Jews kidnapped and murdered the children of Christians to use their body parts or blood in secret rituals, and the BBC says the rumors date back to the Middle Ages. The Spanish Inquisition used it, too.

According to the Jewish Virtual Library, six Conversos (Jews who had converted to Christianity) and two Jews were put on trial in Spain on December 17, 1490. They were tortured and confessed to profanation of a Host and the crucifixion of a Christian child. The trial lasted for almost a year, and at the end, the eight were publicly executed. Three of them were already dead, but don't worry — they were exhumed and executed again.

The verdict was sent to every corner of Spain, and a cult grew up around their supposed victim: the Holy Child of La Guardia. He was never given a name because no victim was actually ever identified and no body was ever found. A shrine to the mystery child was built in La Guardia, which still attracts worshipers.

A two-step torture process

The Spanish Inquisition is always linked to torture, and there was a heck of a lot of that going on behind closed doors. There were a ton of confessions, and researchers have now confirmed that torture just doesn't work when it comes to getting the truth. Why? Simply because most people will say whatever their interrogators want to hear in order to get the pain to stop.

And here's the thing — inquisitors knew that, even in the 15th century. According to the University of Sheffield, inquisitors were perfectly aware of the fact that many people will eventually say anything to get torture to stop. But the inquisitors didn't want that, they wanted an honest confession! So they came up with a two-step process. The evidence the person gave while they were being tortured was recorded, and when the session stopped, they were given a choice: ratify their words or retract them. See, that ratification of testimony was more of an honest confession because it wasn't done under duress. Of course, anyone who retracted their testimony would just be tortured again.

There are a few rare cases where retracted confessions made the whole thing sort of fall apart. In 1539-1540, a group of 40 defendants all retracted their confessions, and their trial actually collapsed.

Torture all you want, but keep it reasonable!

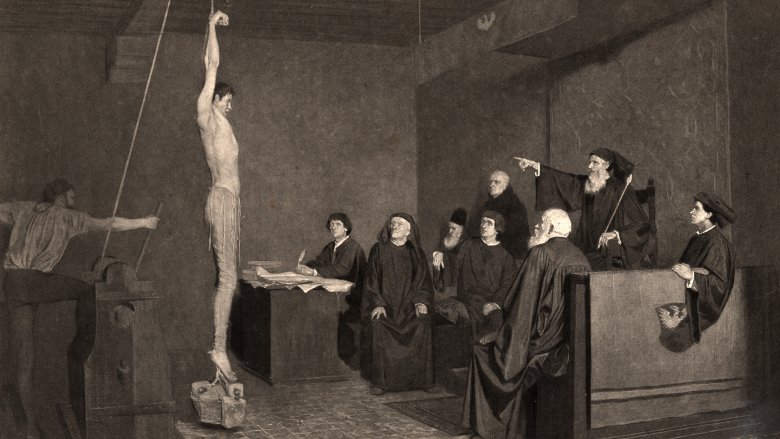

The Spanish Inquisition had a specific set of rules to go by when it came time to torture. The biggest one was they couldn't spill blood, and that meant getting a little creative with their methods. It's why the rack was so popular, along with starvation and something called strappado.

How Stuff Works says that's essentially when the accused has their hands bound and tied to a pulley that hoists them off the ground. Weights might also be attached to them, and needless to say it meant they were hanging from dislocated limbs. Applying pressure was also popular, as was burning with hot tools.

But doesn't burning draw blood? Well, technically, yeah, but Pope Alexander IV had written a loophole into the whole thing during a 1256 precursor to the Spanish Inquisition: Inquisitors could act as witnesses to each other and clear their colleagues of wrongdoing during torture sessions. Convenient!

By the time the Spanish Inquisition got around to their interrogations, the University of Sheffield says they had a formalized document they read from before they got down to torturing. Not only did the very legal document absolve them of any wrongdoing, but it placed the blame for the torture squarely on the person being tortured. The inquisitors, of course, were just doing their jobs.

It followed those who fled

The Jewish Virtual Library calls the expulsion of the Jews from Spain the "pet project of the Spanish Inquisition," and on July 30, 1492, 200,000 Jews were run out of the country. Supposedly as long as there were any Jews in the country they would continue to spread their bad influence around. Some found a welcoming new home in Turkey, but others fled to Portugal ... where they were expelled again in 1496.

And that's heartbreaking. It wasn't enough for them to flee their homes, but persecution — and the Inquisition — followed them wherever they went. In 1566, the Inquisition built New World headquarters in what was then New Spain (now Mexico City). According to the Algemeiner, that mid-16th century build coincided with another event: the founding and flourishing of settlements and colonies in Mexico by Jewish and once-Jewish refugees fleeing persecution in Europe.

Atlas Obscura says the massive Palace of the Inquisition was the site of countless torture sessions, and while they were definitely after converted Jews who were maybe still practicing their original faith, they were also after scholars, scientists, and revolutionaries whose views — religious or political — didn't quite mesh with the mainstream.

Wait, they were still executing people when?

There's something archaic and medieval-feeling about the Spanish Inquisition, and it seems like something that started and ended ages back. But the Inquisition continued for a long, long time — its last victim was executed in 1826.

His name was Cayetano Ripoll, and according to the World Union of Deists, he first embraced the philosophies of deism while he was held by the French as a prisoner of war during the Peninsular War. When he returned to Spain he became a schoolteacher, and he made sure to teach his students the basics of his newly adopted philosophy. (Deism is basically the idea that God can be worshiped and revered through the discovery of rules and wonders found in the natural world, rather than in the so-called "revealed" religions like Christianity.)

Ripoll was arrested and imprisoned for two years until he was finally hanged by the Inquisition. Why hanged instead of burned at the stake like so many others? Because the inquisitors didn't want to shed blood and no secular authority would kill him, so they settled for burying him in unconsecrated ground, in a barrel painted with flames.

It was another few years before the Spanish Inquisition officially ended, says the Nashua Telegraph. It wasn't until July 15, 1834, that the regent acting for the young Isabella II issued a decree to end the Inquisition.

There's no age limit on heresy

Everyone who's ever had any prolonged experiences with kids knows they can be kinda dumb, so you might think they would have gotten a pass on heavy-hitting topics like faith, belief, and heresy. Not so much.

Women were typically home with the servants, the Jewish Women's Archive says, and servants were favorite informers of the Inquisition. Women were in charge of many of the religious rites and rituals in the home, making them — and the children they were teaching — particularly dangerous.

Take Ines Esteban, who was just 12 years old when she attracted the attention of the Inquisition. According to the Jerusalem Post, she began sharing stories of the conversations she regularly had with her mother, who spoke to her from heaven. Ines even claimed to have ascended to heaven for visits where she saw angels and was given small tokens as proof she'd been in the divine realm. People gathered to hear the messages she brought back, and they followed her teachings, too — which included things like observing Shabbat and believing the words of the Torah.

She was arrested in April 1500. Official records of what happened to Ines no longer exist, but the writings of her followers suggest she was burned at the stake by August 1500.

The torture technique still used today

It's no secret that President Donald Trump says a lot of controversial things. One of his more controversial opinions came in 2017: his belief that waterboarding works. (It, like other torture, does not work.) But Trump, like most people, probably doesn't know the technique was developed by the Spanish Inquisition as one of their bloodless torture methods. According to The World, the first documented use of waterboarding comes from the records of the Spanish Inquisition.

There was a small difference, though. For the Spanish Inquisition, their torture-by-water methods had a little variety to them. One method involved forcing a funnel into their victim's mouth and pouring an unthinkable amount of water into them. Another involved pouring smaller amounts of water over someone's head to create that nearly drowning feeling, and it was done over and over and over again. It wasn't just a practice in Europe, either — it was done by all the branches of the Spanish Inquisition.

They didn't even get their hands dirty

Early on in Game of Thrones, readers are introduced to the idea that anyone who passes a death sentence on another person should be willing to take that life themselves. It makes the sentence real, after all. But the inquisitors didn't have George R.R. Martin for inspiration, and they never swung their own swords — or, more accurately, didn't light their own bonfires.

Instead, the Inquisition would hold an auto da fe (act of faith) after people were convicted. According to the Jewish Virtual Library, the auto da fe was the final step in the process, and it was essentially fulfilling a person's penance in public. There was usually a sermon (that could last for hours) in a town or city square, parading of the guilty, reading of the sentences, and prayers, but executions and floggings weren't on the schedule.

Inquisitors weren't allowed to shed blood, and that included doing the actual killing. The Church didn't actually want to be associated with killing the faithless, either, so that was left up to secular authorities, who stepped up to do the killing and burning after the guilty parties were publicly scorned and humiliated. The transfer of prisoner from Inquisition custody to secular was called "relaxing" the guilty party, who would then be taken out of the church's line of sight and disposed of in a way apparently suited to the most heretical in history.