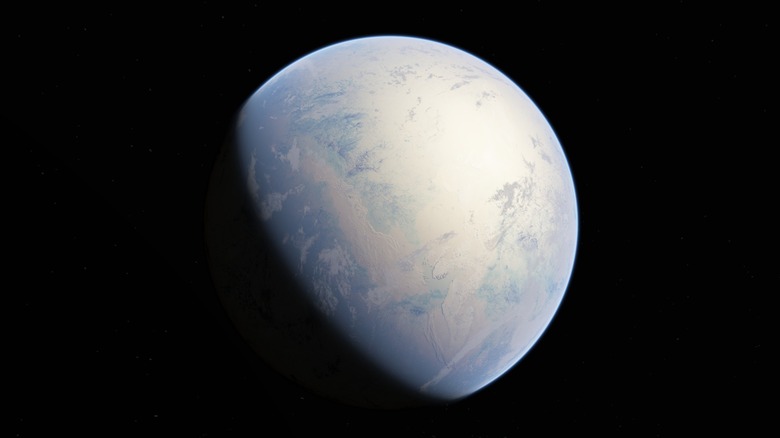

What Researchers Think Snowball Earth Was Really Like

Going about daily life, caught up in everyday concerns like remembering to pay a bill on time or forgetting to buy toilet paper at the store, it's easy to forget how absolutely brief and small a single human life is — no matter how unique and valuable. A meeting at work might "feel like forever," and a 95-year-old grandmother might seem ancient. A 300-year-old building might look like it belongs to a different world, and a 3,000-year-old redwood tree might seem incomprehensibly old. But in order to understand Earth's entire geological history we've got to pull back so, so far that even a million years is just a long weekend. And 60 million years? That was just an extra long, frigid, ice-and-snow-saturated winter.

From about 717 to 661 million years ago Earth entered the "Sturtian Snowball Earth event," as new research on ScienceDirect explains. We've known for quite some time that Earth has a geological "pulse" of cycles — typically 27.5 million years in length, per ScienceDaily — and used to be a giant snowball, but now we have specifics that shed light on the cause and conditions of Snowball Earth. As a Science Advances article explains, for about 2 million years Earth's volcanoes raged non-stop, and lava cooled into igneous rock that sucked up all the carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. This plunged Earth into a glacier-strewn, frozen icescape that might have contributed to the rise of multicellular animal and plant life as we know it.

[Featured image by Oleg Kuznetsov via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 4.0]

Silence, fire, and ice

When envisioning Snowball Earth, forget any ideas you've got about snow-covered woodland glens, 6 inches of powder pushed off car windshields, or anything at all resembling current-era Earth with a whole bunch of snow dumped on top. The geological time period from 717 to 661 million years ago ended a full 130 million years before the first eel-like vertebrates squirmed through the ocean, 276 million years before the first trees, 428 million years before the first proto-mammals, and about 658 million years before the first humans strode across Africa, as New Scientist outlines. Snowball Earth wasn't just "Earth, but cold and snowy" — it was an utterly alien planet unrecognizable next to its current form.

In fact, Snowball Earth more or less started at the end of what's known as Earth's "boring billion," a colossal 1-billion-year span of time from about 1.8 billion to 750 million years ago when not much seemed to happen on the surface of the planet. Geological activity was sparse during this period, and volcanic eruptions quiet. As The Conversation describes, Earth's oceans were mammoth vats of sulphur and iron brewing and simmering with the rudiments of multicellular life. It took this entire period to give rise to a lifeform that would reshape the atmosphere into something recognizable and oxygen-rich: algae. And then, a short 33 million years after the boring billion came to a close, Earth erupted and ignited into the flames of volcanic activity that lasted for 2 million years.

Endless CO2-absorbing volcanic rock

Snowball Earth wasn't a place of spread-around continents with a bunch of water in between. At the time Earth's tectonic plates had slid together into one mega-continent called Rodinia, centered along the equator, per NASA. All of the snow and ice on Earth's surface would have reflected sunlight back into space and had the compounding, increasingly cooling effect of freezing the planet even more. And so, the surface of the planet wasn't chilly and slushy, but cloaked in stone-hard ice and glaciers dominating the landscape.

Scientists debated the cause of Snowball Earth for some time before recent studies emerged. Back in 2019 Astronomy suggested that volcanic activity — which created "sulfur aerosol emissions," per Science Advances — could have caused it by blocking incoming sunlight. These, however, dissipate pretty quickly. Instead, new evidence suggests that all the igneous rock blurted onto the surface of the Earth from volcanic eruptions acted as a heat sink that absorbed much of Earth's planet-warming carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Two million years of eruptions over a large enough area — the Franklin Large Igneous Province in Canada, spanning nearly 1 million square miles — produced enough igneous rock to freeze the entire planet for 60 million years.

Fossil records demonstrate that after Snowball Earth warmed up, multicellular life expanded dramatically across the planet during what's called the Ediacaran period, as Open Geology tells us. Why this happened, and even why Snowball Earth ended, remains a mystery.