Who Was Lady Columbia, The First Symbol Of Hope In The US?

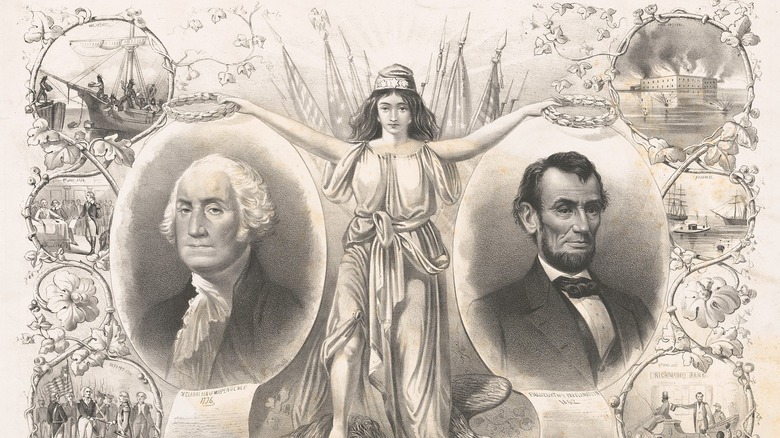

Before the Marvel movie franchise recast Captain America into a badass, the stars-and-stripes-wearing, shield-toting, wing-helmeted comic book character might have come across as silly or hokey to non-comic fans. After all, how blatant of a propagandistic symbol of "freedom, liberty, hope, etc." could a character created in 1941 — the year World War II broke out — get? Well, it turns out that if you dial the timeline backward 250 years or so you'll find another incarnation of the same heroic figure meant to represent how the "New World" embodied Enlightenment values of progress, tolerance, free-thinking, etc.: Lady Columbia. Come 1890 she was even depicted with a red, white, and blue shield emblazoned with a bald eagle.

The first mentions of Lady Columbia — originally called Columbina — show up toward the end of the 17th century about 80 years before the signing of the Declaration of Independence in 1776. At this point, the future United States was just a collection of British colonies on a far-flung landmass across the Atlantic Ocean. As the National Museum of American History says, Chief Justice Samuel Sewall of the Massachusetts Bay Colony started including Columbina — the feminized version of Columbus, after Christopher Columbus — in his poem as a mythological, goddess-like figure meant to represent the values of the American colonies. Even though Columbia has since been supplanted by Lady Liberty and outlived by Uncle Sam, folks have at least seen her if they've seen the Columbia Pictures movie logo.

[Featured image by Willard and Dorothy Straight Collection via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | Library of Congress]

A modern-day Athena to embolden and inspire

"Columbia's arm prevails ... Proceed, great chief, with virtue on thy side / Thy ev'ry action let the goddess guide," Smithsonian Magazine quotes poet Phillis Wheatley writing to Commander of the Continental Army George Washington in 1775 at the advent of the United States' Revolutionary War. We don't know exactly how, but by then the figure of Columbia had caught on well enough to be offhandedly referenced in a letter meant to embolden and inspire Washington. In fact, as an article from The New England Quarterly writes, by 1761 Britain's colonies were often referred to as "Columbia" to differentiate them from "Britannia," the Old World.

Even though it might seem weird to create a deity or entity meant to embody to a group or nation out of thin air, this kind of thing still happens all the time — we need not look any further than mascots for sports teams. For Columbia's part, she was meant to evoke classical lore ala figures like the Roman goddess Minerva or the Greek goddess Athena, the grand and majestic lady of wise counsel, warfare, and civilizing arts like weaving and pottery. And indeed, depictions of Athena are eerily reminiscent of Columbia, right down to their most characteristic, shared item: a shield. There's even a life-size statue of Columbia at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History depicting her wearing a hat reminiscent of Athena's iconic, curved helmet.

[Featured image by Popular Graphic Arts via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | Library of Congress]

From indigenous woman to guiding spirit

As Obscure Histories discusses, Columbia and her appearance — a young, beautiful, powerful woman — might have been arisen from earlier artwork depicting the European discovery of North America. These are the kinds of paintings, sketches, etc. that circulated amongst Europeans who were curious about the voyages back and forth between the old world and the new. An early piece of art from 1600 called "Allegory of America, from New Inventions of Modern Times" depicts "America" as a naked indigenous woman sleeping in a hammock as a European traveler stumbles across her. A later piece of art from 1662, also called "Allegory of America," depicts a native woman walking amidst imagery like a salamander and gold bars (the exoticism and wealth of America), a bunch of angels in the clouds, and ships carrying goods back to Europe.

It was over 110 years later that poet Phillis Wheatley cited Columbia in his letter to George Washington in 1775 when the U.S. Revolutionary War broke out. As Obscure History says, he's the one responsible for concretizing the physical appearance of Columbia into that of a poetic war goddess with "golden hair" composed of equal parts masculine and feminine identities. After this Columbia appeared side by side the U.S.'s newer mascot, Uncle Sam, during the War of 1812. Eventually she changed with the times through the Westward Expansion and the great surge of immigrants coming to the U.S. through the late 1800s to early 1900s.

[Featured image by John Gast via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | Library of Congress]

Defender of the downtrodden

Moving into the mid-1800s, Columbia became a go-to figure for whatever pertinent issue took center stage at that time, including acting as a reproachful maternal figure disciplining squabbling politicians. As seen on the Library of Congress, one 1860 political cartoon shows politician Stephen Douglas over her knee as she spanks his bottom for proposing that slave-holding be left to individual states. In a later, famed 1872 painting by John Gast, Columbia flies above waggoneers like an ethereal spirit guiding them westward across America's vast landscape. And of course, whenever there was a war — like World War I — you could count on seeing Columbia on a poster beckoning people to enlist.

But perhaps most interestingly, one of Columbia's final, major roles before she faded into obscurity was as a champion of the downtrodden and oppressed. Obscure Histories, for example, shows Columbia on a 1871 poster defending a Chinese man from a murderous crowd — it reads, "Hands off, gentlemen! America means fair play for all men." An 1881 illustration shows Columbia welcoming a column of migrants, reading, "Columbia welcomes the victims of German Persecution." She also showed up as a statue overlooking the 1893 Chicago's World Fair, aka the World's Columbian Exposition. But around when the Statue of Liberty got reassembled on American shores in 1886, Columbia had become something of a redundant figure. People started looking to the large copper guardian of Ellis Island and the Hudson River, instead.

[Featured image by George Grantham Bain Collection via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled]