Major Historical Events You Didn't Learn About In School

School history books are designed to make students think everything is cool. Good defeats evil, progress defeats stagnation, and war doesn't suck that much. As adults, we know that the sanitized version of history doesn't tell the whole truth, and probably not even most of the truth, but we don't complain because we mostly don't want to have to spend a lot of time explaining to our children that good doesn't always defeat evil, progress doesn't always defeat stagnation, and war sucks in just about every way possible. After all, kids who believe in justice grow up to be adults who try to make the world a better place. So let's just let the little buggers discover history's sad truths for themselves, when they become disillusioned teenagers. And also, make sure they don't find out about the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution until they are well into their 20s. Civilization as we know it pretty much depends on it.

When America made native people march 1,200 miles

In school, kids learn that there were native people in the Americas when Europeans arrived, and that some of them partied with the Pilgrims around about 1620, and it was a big kumbaya friendship thing, and then history teachers kind of just skip over the rest of it.

The truth is there was never really any kumbaya between Europeans and the native people of America. At best it was tolerance, at worst it was genocide. One of the most compelling examples of just how much America did not care to kumbaya with the native people was the Indian Removal Act of 1830, which was the law that legislated the practice of booting native people off their own lands.

According to History, the act didn't actually say it was cool to forcibly remove anyone, but Andrew Jackson, who was president at the time, really didn't give a rodent's buttocks about the particulars. So in the winter of 1831, the Choctaw not only got the boot, they were forced to make the long journey to Oklahoma on foot, sometimes in chains, and without any food or supplies. The Creeks were next, and then in 1838 the Cherokee, who were put into stockades while whites got to loot their homes and take all their stuff. Then they, too, were forced to make the 1,200 mile journey to Oklahoma. More than 5,000 of them died from disease and starvation along the way, and we remember it as the Trail of Tears today for a reason.

When some guy blew up a horse-drawn cart on Wall Street

You might remember the Oklahoma City bombing of 1995, when Timothy McVeigh blew up the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building with a Ryder truck full of explosives. What you probably don't realize is that the attack was not the first time someone parked an exploding vehicle in front of an important building — in fact, that sort of thing hasn't been novel for at least a century.

According to the FBI, in 1920 some guy filled a horse-drawn cart with explosives and parked it in front of the U.S. Assay Office on Wall Street. Then, without even bothering to unhitch the poor horse, he ran off. The cart exploded, killing 30 people and probably also the horse. At least 300 people were injured, and many of them died in the hours that followed. It's an awful story with a familiar ring to it.

Terrorism has been happening in America at least since people first figured out how to blow stuff up. Dynamite was patented in 1867 (ironically, by the same dude whose name is attached to the Nobel Peace Prize), and by 1886 America's first peacetime dynamite bomb was tossed into a crowd of protesters and police officers at Haymarket Square in Chicago. So by the time of the Wall Street bombing, there was already a three-decade history of bombings on U.S. soil. And in those days, forensic science wasn't exactly sophisticated, either, so the crime remains unsolved.

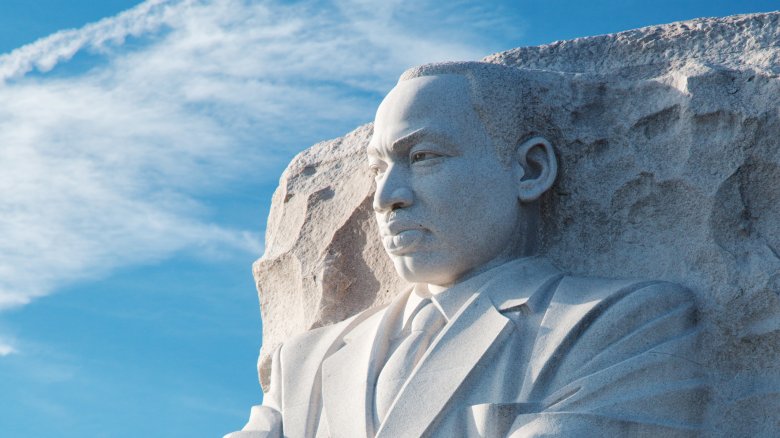

When MLK united blacks, whites, Latinos, and indigenous Americans

Martin Luther King Jr. is remembered mostly for his fight to achieve racial equality and end segregation, and practically no one remembers the other work he did. According to MLK Global, at the time of King's assassination he was also involved in the Poor People's Campaign, which was a movement that aimed to gain basic employment and housing rights for people of all colors. The movement included blacks, whites, indigenous Americans, and Latinos, and was partially rooted in King's disillusionment over what his civil rights campaign had been unable to accomplish — an improvement in the living conditions of African Americans.

The movement was planning to set up a tent city in Washington in the summer of 1968, where thousands of protesters would remain until the government met their demands. But King was assassinated in April of that year, and the march was instead led by his widow, Coretta Scott King. Around 5,000 people marched to Washington, where they were met by 20,000 soldiers, just in case they decided to start waving pitchforks around or something.

The ultimate goal of the Poor People's Campaign was an "economic bill of rights," and you can probably guess how far that idea got since life as a poor person in America still sucks pretty much as deeply as it did in the late 1960s. No economic bill of rights was ever passed, many protesters were arrested, and the tent city was shut down.

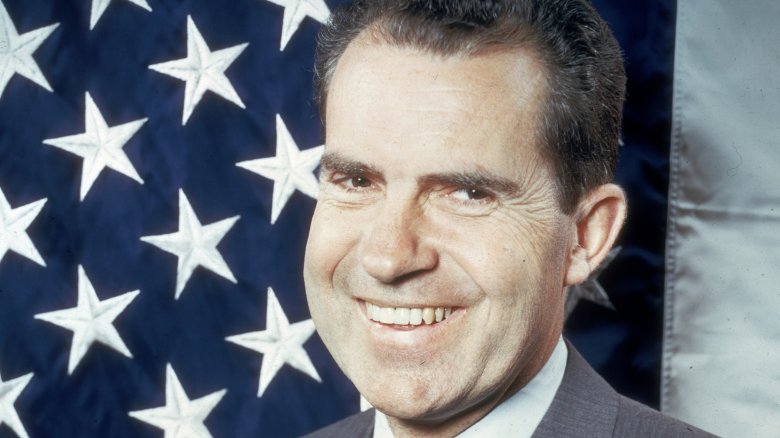

When Nixon supported the wrong guy and indirectly killed almost 2 million people

When Richard Nixon uttered the words, "I am not a crook," he went down in the history books as the crookiest crook of all time, the Watergate guy, the only U.S. president to resign before the end of his term, and one of the ubiquitous heads-in-a-jar on Futurama. Ultimately that was all a good thing, at least as far as Nixon was concerned, because in the shadow of Watergate and all that other stuff almost everyone forgot about Cambodia.

According to UPI, it was Nixon's support of strongman Lon Nol and a U.S. bombing campaign that allowed the communist Khmer Rouge movement to grow and prosper, which eventually led to the deaths of 1.7 million people, or roughly one in five Cambodians. After seizing power, the Khmer Rouge forced a couple million people into the countryside to become farmers, so they could have some bizarre utopian society of agrarian self-sufficiency, and meanwhile they also killed all the intellectuals, soldiers, and minorities while everyone else was busy dying of starvation and disease. This happened pretty much immediately after the Vietnam War, which might explain why it wasn't talked about much — perhaps people in the U.S. were worn out by the endless conflict in that part of the world, and they just wanted peace and love, man. (But mostly just in the U.S., screw everyone else.)

When Bacon united blacks and whites

One hundred years before the American Revolution, bacon brought blacks and whites together. Not bacon maple cupcakes or baconnaise (although let's face it, those things do have the power to unite the world), but some guy whose name was Bacon and was probably pretty close to making all the aristocrats in Virginia wet their collective pants. There's nothing like a revolt to let the elite know how pissed off the non-elites are, but in the 1670s the idea that blacks and whites could band together and form a unified front toward a common goal must have been utterly terrifying for the few rich, white dudes who were controlling everything.

Now, never mind that Bacon's rebellion was set off by a desire to fight indigenous people — according to History is a Weapon, Bacon himself was a white landowner who thought "Indians" were threatening his security, and wanted the government's help in beating them back. In the process, he became a symbol of sticking it to the man as those grievances grew to include things like over-taxation and elitism.

Bacon was joined by both poor, white servants and black slaves, who hoped the rebellion would lead to a redistribution of wealth. It didn't succeed, and it also had a pretty insidious residual impact — it institutionalized racism, by making it clear that the best way to keep unhappy whites from joining forces with unhappy minorities was to make sure that they were divided by a deep dislike of each other.

When Americans massacred Native Americans for like the billionth time

There aren't still bands of Native Americans roaming the plains, hunting buffalo, and hanging out with Kevin Costner, so we all intuitively know that at some point, the Europeans won, subdued the indigenous people, and went on to make the world a crappier place. But kids in history classes don't usually hear about the end of the Indian Wars because like pretty much everything that happened during that time, it was horrific and doesn't really do much to support the idea that America is the land of equality and justice for everyone.

By the end of the 19th century, the Sioux had lost their land and their way of life, and like anyone facing a bleak future, were looking for something to believe in. According to Eyewitness to History, many joined the Ghost Dance movement, which promised that if devotees danced long and hard enough, "a tidal wave of new soil would cover the earth, bury the whites, and restore the prairie."

The whites in charge of keeping order were sort of freaked out by all the dancing, so they called for support, launching a chain of events that led to a confrontation at a creek called Wounded Knee. As the Sioux were attempting to negotiate with the army, someone fired a single shot, panic ensued, 300 men, women, and children ended up dead, and America had to start the whole equality and justice thing all over again.

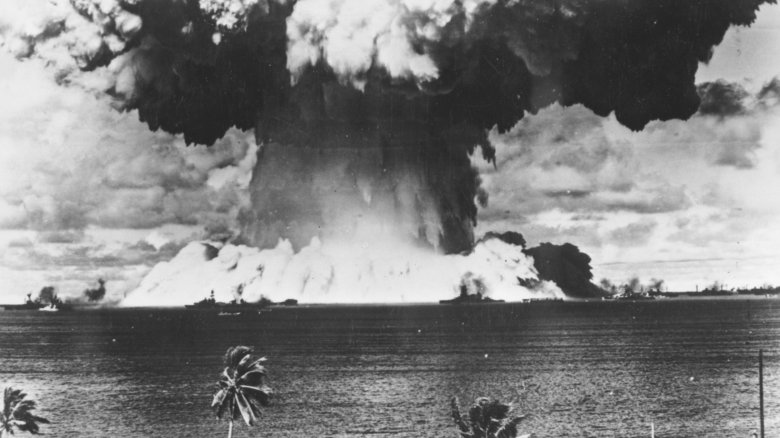

When the military tested nuclear weapons in someone else's homeland

After the end of World War II, the United States assumed control of the Marshall Islands as part of the "Trust Territory of the Pacific." The Marshall Islands is a pair of tiny island chains in the Pacific Ocean, between Hawaii and Papua New Guinea, occupied by a small population indigenous people. Now, you would think that the phrase "Trust Territory of the Pacific" implies that the United States intended to look after the islands, but that's not really how the U.S. saw it. No, to the government, having control over a small collection of islands way out in the middle of the Pacific Ocean was a golden opportunity to get away with stuff.

According to the Guardian, in 1946 the government told residents of Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands that they'd better leave because stuff was about to blow up. Literally. Between 1946 and 1958, the United States conducted 67 nuclear weapons tests, including a nearly 15-megaton hydrogen bomb that had the explosive power of around 1,000 Hiroshimas and left a crater "several hundred feet deep" and a half mile wide. It's okay, though, because scientists deemed the atoll totally safe for resettlement just 20 years later, and the Marshall Islanders returned, only to be told eight years after that that oops, they'd better leave again because all the food grown on the islands contained dangerously high levels of radiation. "Trust" is such a malleable word.

When Mao told Chinese teenagers it was okay to kill people

In the mid 1960s, Mao Zedong, chairman of the Chinese Communist Party, decided that something needed to be done about all the people in the Chinese government who had been annoying him over the years. So he launched the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, which was basically a decade-long campaign of brutality and political upset that was ultimately designed to make Mao more powerful.

According to the Guardian, the revolution began when the communist party gave citizens permission to "clear away the evil habits of the old society," which teenagers interpreted as "destroy things and kill people." Churches, shrines, stores, libraries, and people's houses were all fair game, and were set upon by gangs of teenagers doing what teenagers everywhere would do if authority figures suddenly told them that wanton destruction was totally cool. The goal of the revolution was to punish communist officials for being too "bourgeois," or not dedicated enough to the principles of communism, which was pretty handy for Mao since he was the only official not subject to that kind of discretion. Anyway, the revolution ended a decade later when Mao died, and by then the body count was somewhere between 500,000 and 2 million. So the lesson we can learn from this little piece of history is clearly, never underestimate the destructive power of unbridled teenagerism.

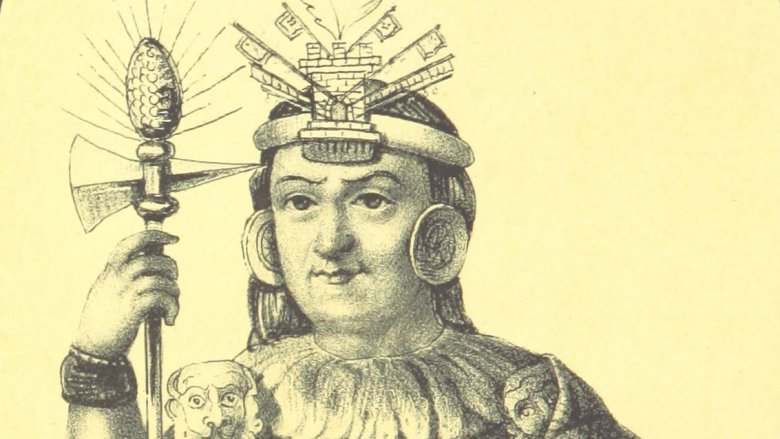

When a puppet king told the Conquistadors what to go do with themselves

In 1533, the Spanish conquistadors decided they needed a puppet emperor so they could control the Inca empire but not make it look too much like they were the ones pulling the strings. So they picked Manco, the 19-year-old brother of the recently executed Atahualpa.

For some reason it never occurred to any of the conquistadors that Manco might get tired of all the ceremonies, meaningless appearances, and private torture sessions meant to compel him into giving up Incan treasure. According to ThoughtCo, Manco devised a clever plan to escape — he told his captors that he had to do some ceremony stuff in the Yucay Valley, and by the way there was a gold statue there, so of course they had to let him go so he could pilfer the statue for them. The conquistadors were all, "Cool, go get the statue," and then Manco ran off and summoned an army of 100,000 Inca warriors.

Manco's army drove the conquistadors back, but the conflict ended when Spanish reinforcements arrived. Manco retreated and went into hiding before launching a guerrilla campaign that lasted seven years, until his assassination in 1544. Just in time for the conquistadors — when Manco died he'd been teaching his warriors how to use the Spaniards' own weapons against them, and if that had gone on much longer it might have changed the direction of history.

When the USA entered the Vietnam War for no apparent reason

You will be super shocked when you hear that sometimes governments lie so they'll have excuses to go to war. Not the United States, though, because the United States has always been the world's moral authority, and if you're not laughing right now it's because you haven't been paying attention.

According to the U.S. Naval Institute, the Gulf of Tonkin incident was America's excuse for entering the Vietnam War, but recently declassified information suggests that North Vietnamese patrols did not, in fact, launch an unprovoked attack on an American destroyer — the destroyer fired first. Now granted, they were warning shots, but they led to a confrontation that ultimately led to nearly a decade of direct U.S. involvement in Vietnam.

The Gulf of Tonkin incident is a lesson in the fact that even relatively open, accountable governments lie, which explains why the details were buried in classified documents for so long. But that's not the kind of thing that's likely to end up in public school curriculum any time soon, and really if you're asking, the entire Vietnam war and all the wars before and after it also aren't likely to ever be covered honestly in school textbooks, which tend to sanitize and downplay the actual suckiness of war. Because no one wants to be the teacher who convinced students that serving in the military might be dangerous and terrifying and also you might end up going to war for really terrible reasons.

When the Russians killed the Romanovs and became the great villains of the 20th century

Pretty much every kid who grew up in the '80s knew we were supposed to hate Russia because of reasons. But no one really bothered to explain what those reasons were, or what path the Russians went down before officially becoming the Big Bad of the 20th century.

Like all great political changes, Russia's transition into the Soviet Union began with a revolution. According to History, the Russia of the early 20th century was poor — there were a lot of peasants and impoverished industrial workers, and living conditions were pretty abysmal. Then in 1914, the czar made the fatal mistake of entering World War I. This was expensive, unsuccessful, and made things even worse.

By 1917, people were pissed off, the Bolshevik revolutionaries had widespread support, and everyone was ready for a change in leadership. The revolution forced the czar to abdicate his throne, but that evidently didn't satisfy everyone because by June of the following year the Bolsheviks sentenced the czar and his entire family to death, and then shot them in their own basement. (The youngest, Alexei, was only 13.) And so Russian imperialism ended, and the Soviet Union was born, and things got so much better. Not really, but the Soviet leadership did such a great job of convincing everyone that things were better that even today, plenty of Russians still pine for the good ol' days of communism. Behold the power of propaganda.