The Most Inbred People Throughout History

For most people, carrying a recessive gene isn't necessarily a death sentence. It's only when that person links up with another carrier of the same bit of genetic code that their children might be in danger. They run the risk of getting both recessive copies and suffering from a recessive disorder. With a relatively large and diverse gene pool, those incidents are pretty rare. But, if someone is restricted to picking a partner only from their family, that chance can start to rise dramatically as successive generations collect identical or near-identical bits of genetic code, a state known as homozygosity.

As for why inbreeding happens, it could be due to many different factors, including geographic isolation, social restrictions, or rare but brutal incidences of abuse. Some groups may simply want to follow familiar traditional paths, marrying people from similar stations who, over time, tend to all become related. Historically speaking, royal dynasties have been especially prone to inbreeding, as family members aren't terribly interested in sharing their ridiculous amounts of wealth and power with outsiders. Social beliefs, like ones that claim certain people are special or even divine, can make hooking up with mundane folks all the more unappealing. Why would a demigod dilute their bloodline with mortal genes, after all?

All of this means that, throughout history, a small number of people have become seriously inbred. Some escaped the worst effects of their tangled family tree, while others are painful examples of why inbreeding is so often considered a taboo.

Tutankhamun

Though ancient Egyptian artists weren't afraid of realism, it probably wouldn't have been the plan to show the dead pharaoh Tutankhamun exactly as he had been in life. The glimmering, symmetrical glory of his golden death mask covered a human being who was likely highly inbred and suffered for it.

What exactly did Tutankhamun have going on? According to a 2010 study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, CT scans of his mummy showed that the young king, who died aged just 19, was dealing with a lot of things. First, there was the broken leg and active case of malaria, which may have been the immediate issues contributing to his death. He was also managing scoliosis and a cleft palate while also suffering from a clubbed foot that would have made walking difficult. This was further exacerbated by a degenerative disease that was eating away at the bones in his left foot.

Like with so many ancient and historic people, it's hard to say for sure if Tut's issues were all linked to his inbreeding. However, the study did confirm that he was almost certainly a product of royal inbreeding. The pharaoh believed to be his father, Akhenaten, did marry one of his sisters. Tut was also married to his own sister (or half-sister), perhaps explaining why he had no heir and was buried with two miscarried fetuses.

Ancient Irish royals

Like in so many kingdoms across the span of human history, the royals of ancient Ireland weren't exactly keen on sharing their wealth with outsiders. At least, that seems to be the only explanation for the genetics of one man who was buried in the stunning Newgrange tomb built in Neolithic Ireland. Per a 2020 paper published in Nature, the individual in question was found in an especially well-appointed section of the stone tomb, which was already believed to be set aside for the elites of the era.

While analyzing the genomes of more than 40 individuals who had been buried in and around Newgrange, researchers found that this man's particular genetic code was very closely knit. More specifically, they found that he had to have been produced via first-degree incest. He was almost certainly the product of a sibling or parent-child union. Researchers also determined that he was related to others buried nearby, further showing his links to the upper echelons of the area over 5,000 years ago.

Though there isn't much of a written record to back up this claim, the DNA is hard to ignore. So, too, is the circumstantial evidence that indicates only the upper echelons of Stone Age Irish society were engaging in this practice. Poor farmers weren't being laid to rest in an elaborate tomb, after all. It may therefore echo similar situations in other ancient societies, including the courts of the Egyptian pharaohs and early royals in the Hawaiian kingdom.

Short Creek FLDS families

For the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (FLDS), the drive to keep within their highly conservative religious group is also paired with the directive to have as many children as possible in polygamous marriages. Yet, the FLDS community of Short Creek on the border between Utah and Arizona has begun to see the effects of generations of inbreeding up close.

The problem was first identified by pediatric neurologist Theodore Tarby, who examined a young boy from the community in 1990. The child presented with unusual facial features and significant developmental delays. Tarby found that the boy had a rare genetic disorder known as fumarase deficiency, which kneecaps the body's ability to supply energy and dramatically affects brain development. Affected people have cognitive impairments, seizures, and physical disabilities. Former FLDS member Faith Bistline told the BBC that she cared for five cousins with fumarase deficiency. Just one could walk and all required intensive care, including feeding tubes.

Fumarase deficiency was so rare that just a handful of cases were known at the time. But, eventually, doctors found a staggering eight new cases in the FLDS community at Short Creek, as they reported in a 2000 issue of Annals of Neurology. Clearly, this was more than a case of random genetic mutation. Instead, the small pool of marriageable adults is to blame, made all the smaller because men are expected to take multiple wives (cutting out other men and their genes entirely).

Charles II of Spain

When it comes to inbred royals, poor Charles II of Spain is the unfortunate poster child. Of course, it wasn't his fault that he was born into the Habsburg dynasty, which by his 1661 birth was notoriously inbred because the Habsburgs couldn't bear to dilute their wealth and power via marriage with outsiders. It all became so tangled that Charles' parents were niece and uncle, while his grandmother did double duty as his aunt.

Charles was beset by a staggering range of problems, from physical deformities that included the dramatically jutting Habsburg jaw characteristic of his family, developmental delays, epilepsy, and even early-onset baldness that was obvious by his mid-30s. After his death at the age of 38, doctors performed an autopsy and wrote that he supposedly had a heart so small its size was comparable to a peppercorn, not to mention badly damaged internal organs and just a single, blackened testicle. Some details sound exaggerated, but it's nevertheless clear that Charles had been dealt a terrible genetic hand.

Perhaps most damaging to Charles and the entire Habsburg clan was the fact that he couldn't produce an heir. He was married twice but never managed to have a child. The disorders behind all of this remain unknown, though modern researchers have suggested genetic kidney disorders, enzymatic issues, and a malfunctioning pituitary gland as the culprit. Whatever was going on, Charles' failure to carry on the line spelled the end of the highly inbred Habsburg dynasty in Spain.

Ancient Hawaiian royal family

In the early days of Hawaiian culture, almost everyone was subject to an intensely hierarchical way of life. Many were simple commoners known as maka'ainana, while konohiki were in the middle. A select few called the ali'i sat at the top of the social pyramid and could be divided into even smaller ranked categories. A complicated set of social rules, known as kapu, demanded such respect for the ali'i that the highest-ranking chiefs would expect most people to fling themselves face-down in their presence. Breaking kapu could spell death, though the system was abolished by royals in the early 19th century.

Before that sea change, however, the ali'i were seriously restricted when it came to selecting a spouse. The solution, at least in ancient Hawaii, was to marry one's first-degree relative. The practice was once revered and considered a mark of the highest status, with children produced from these unions seen as especially high-ranking. But Europeans who settled in the islands were downright horrified by the practice. By the 1820s, King Kamehameha III and his sister, Nahienaena, were caught in an emotionally fraught middle ground. The two were reportedly very close and attempted to wed, but Nahienaena — caught between the old ways and the desire to throw herself into the new Christianity brought by missionaries — was later persuaded to marry another. Supposedly, however, she still had a child by her brother, but the boy died shortly after birth. Nahienaena herself died aged about 20.

Queen Victoria's family

Queen Victoria of England seemed healthy enough, but her descendants weren't quite so lucky. Victoria carried the gene for hemophilia, a recessive disorder in which blood doesn't clot properly and sufferers are at risk of bleeding to death. Because it's linked to the X chromosome, inheritors with XY chromosomes are at greatest risk, given that they have no other X chromosome that might carry a dominant gene to counteract the recessive one. Victoria's own son Leopold died of hemophilia at just 30 years old.

Though Leopold was the first of Victoria's descendants known to have hemophilia, he was very definitely not the last thanks to the limited gene pool of European royals. Victoria's granddaughter Victoria Eugénie brought the gene to Spain, while three grandsons died of the disease. Victoria's other granddaughter Alexandra carried it all the way to Russia and her only son, Crown Prince Alexei. That offered an opening for the notorious mystic Rasputin to work his way into the graces of the imperial family after he supposedly helped Alexei.

Because the royals kept the heir's genetic condition under wraps, few understood why Rasputin appeared to have so much sway over Alexandra and her family. This reportedly led to more destabilization, to the point where Rasputin was killed, the Romanovs were assassinated in 1918, and Lenin and company took over a newly communist Russia. Was Victoria's hemophilia gene, amplified by decades of inbreeding, solely to blame? No, but it definitely didn't help things, either.

The Colt family

Unfortunately, some of the worst cases of inbreeding in the modern era come from deeply abusive environments. Take the Colt family of Australia. This isn't their real name, as "Colt" is a court-provided pseudonym meant to protect minor children caught up in the abuse. And that environment proved to be especially horrifying, as police uncovered beginning in 2010. In 2012, 12 children were removed from the family's rural compound near Boorowa, New South Wales, where adults were accused of severely neglecting the children's education, hygiene, and nutrition.

Further investigation revealed something even more disturbing. Multiple children had learning disabilities and one reportedly had unusual facial features. It soon came out that some had been sexually abused by members of their own family, and that some were products of that abuse.

It all came about when "Timothy" and "June" moved to Australia from New Zealand in the 1960s. Court statements from 2013 indicate that June was the daughter of a brother-sister pair (via New Zealand Herald). After June married Tim Colt, the couple moved to Australia and had seven children. Over the years, Tim abused his own children and grandchildren, while other family members did much the same. Though some daughters denied the abuse, DNA testing made the truth all too clear. Now, Colt family members still suffer from the genetic effects of inbreeding and years of social isolation and neglect that have made joining wider society all the more difficult.

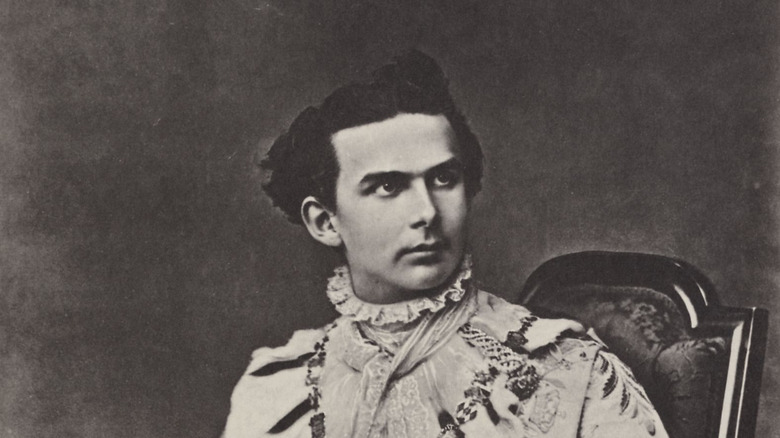

Ludwig II of Bavaria

For many European royals, the pressure to pick a spouse from a suitable (and closely related) family was too much to ignore. The German House of Wittelsbach was yet another European dynasty with a rather in-grown family tree. While few Wittelsbachs could really compare to the obvious issues of Habsburgs like Charles II of Spain, they weren't without some odd behaviors, including mental illness believed to be hereditary and which affected multiple family members. Most dramatic was arguably Ludwig II, who ruled Bavaria from 1864 to 1886. He was generally uninterested in government and instead got busy spending money on extravagant building projects. His most famous is the Neuschwanstein Castle, dramatically perched atop a mountainous ridge and based on Ludwig's idealized love of fairy tales and revisionist history.

Pretty as the never-completely finished castle was, this and other building projects were seen as a symptom of Ludwig's tenuous grip on reality. It didn't help that, by the 1880s, he had become something of a recluse and was declared insane and unfit to rule on June 10, 1886. Just three days later, he died by drowning in a lake near one of his elaborate homes. Some argued that it was an accident, others went with the official verdict of suicide, and others have even claimed that the politically inconvenient "mad king" was murdered.

Ferdinand I of Austria

While some inbred royals might have been able to fly under the radar, others were seemingly so affected by their heritage that simply looking at them offered a clue that something wasn't quite right. Ferdinand I, Emperor of Austria, was just such a person. Born in 1793, his parents were Holy Roman emperor Francis II (also known as Francis I of Austria) and Maria Theresa of Naples and Sicily. The wedded pair also happened to be double first cousins with all grandparents in common.

Though, again, there wasn't such a thing as genetic testing in the late 18th century, that cousin marriage may explain why their son Ferdinand suffered from hydrocephalus (high levels of fluid around the brain), speech difficulty, and seizures throughout his life. Some accounts also claim that he had a cognitive disability. The hydrocephalus also gave him a strikingly large head, if the portraits of the emperor are anything to go by. Poor Ferdinand is even said to have had a seizure in the middle of his 1831 wedding to distant cousin Maria Anna of Piedmont-Sardinia. The two never had children, but at least Ferdinand was good-natured and a relatively popular emperor until political unrest pushed him to abdicate in December 1848. If his genes were the cause of his purported troubles, they didn't much affect his lifespan; Ferdinand died in 1875 at the age of 82.

The Blue Fugates

The stereotype of inbred Appalachians is pretty unfounded, as a 1980 study published in Central Issues in Anthropology found that rates of inbreeding in the region were about the same as anywhere else in the U.S. There are, however, a few exceptions. Perhaps none were more eye-catching than the Blue Fugates.

It all started with Martin Fugate, who moved from France to Kentucky around 1820. There, he married Elizabeth Smith and the couple had seven children, four of whom had blue skin. Both parents carried a recessive gene for methemoglobinemia, a blood disorder in which individuals have abnormally high levels of methemoglobin (a type of hemoglobin) in their blood. However, that protein can't properly release oxygen. The result, at least for some, is cyanosis that leads to strikingly blue skin (depending on the exact disease, others can suffer symptoms like fatigue, seizures, and developmental delays).

Because the Fugates lived in a rural area when long-distance travel was difficult, their descendants had a limited pool of potential spouses. Martin and Elizabeth's son reportedly married his own aunt, for instance. Eventually, the family produced enough blue-skinned members that they became locally known as the Blue Fugates. But as travel became easier, more married out of the group and reduced the rates of methemoglobinemia in the family. With modern medical care, anyone still exhibiting the blue skin can see it fade away within minutes after consuming a tablet of methylene blue, which turns their defective methemoglobin back into hemoglobin.

The Ptolemies

Egypt's queen Cleopatra VII was a legendary beauty — or, so they said. Now, evidence indicates that she was pretty average-looking, though that didn't seem to dampen her immense political power, intelligence, and the charisma she used to win over Julius Caesar and Marc Antony.

She and her family may have also been seriously inbred. Cleopatra's ancestors in the Greek Ptolemaic dynasty, which ruled Egypt from 305 B.C. to 30 B.C., were very invested in keeping it in the family. To that end, her great-great-grandparents comprised only six people (in standard cases, that should be 16 individuals). Cleopatra herself married her brother Ptolemy XIII and, later, another sibling, Ptolemy XIV. These generations of inbreeding may have contributed to the Ptolemaic obesity, which some researchers have suggested may be due to inherited thyroid issues instead of just supremely rich living.

However, it's important to note that ancient genealogies are especially hard to pin down. That's even more so when we're talking about the royals of Ptolemaic Egypt, who had so many wives and children and some not-so-great documentation that getting a clear picture of their parentage is difficult. What's more, Cleopatra herself didn't seem obviously affected by her genealogy, ruling for 21 years before her death by suicide at age 39. She also had four known children, but none by her family members, hinting that perhaps the Ptolemies had a more diverse gene pool than previously suspected.

Kingston clan

For at least some patriarchs of the Kingston clan, power is meant to be maintained at any cost. The Salt Lake City-based group, also referred to as The Order, the Davis County Cooperative Society, and Latter-Day Church of Christ, was founded in 1935 by Charles "Elden" Kingston. It's since reportedly isolated its members with a potent and sometimes violent mix of racism, apocalyptic fear-mongering, strictly enforced patriarchal hierarchy, and anti-government positioning. With its links to the early Mormon church, modern Kingston members also practice polygamy. Elden's brother, Ortell, is reported to have encouraged incest in order to keep up the perceived purity of his family, to the point where he had children with two half-sisters and two nieces. His own descendants have carried on the tradition, marrying half-siblings, cousins, and nieces, many of whom were only teenagers.

Though today Utah state law barely recognizes polygamy amongst consenting adults as a matter of concern, forced marriage and underage marriage are still very much cause for a felony conviction. Members of Kingston group, whose spokespeople have strenuously denied these charges, have instead been given felony convictions for tax fraud in 2023. Kingstons remain tight-lipped about family affairs, to the point where members reportedly fail to list fathers on birth certificates in an attempt to make tracking familial relationships more difficult. The closed-off nature of the group has made investigating the effects of inbreeding difficult, but it has reportedly produced children with visual impairments, unusually small heads, and dwarfism, among other effects.

Ancient Peruvian elites

Though Incan heirs were meant to be the best pick and not simply the first-born son, later royals determined that a ruler's heir ought to come from the son of his chief wife. Political machinations and a desire to hold onto power eventually meant that succession became a closely-held family affair, anyway.

Incan rulers were said to have begun marrying sisters or half-sisters in an attempt to consolidate power and also tamp down the violent scheming that went into pushing one candidate forward over another. If that sounds all a bit far-fetched, there is genetic evidence that intermarriage was very much a thing amongst the ancient people of the region. In 2017, at the conference of the American Association of Physical Anthropologists, Sara K. Becker presented the results of an excavation at a Peruvian burial site covering A.D. 500 – 1100 (via Forbes). Excavators found 14 individuals with a highly unusual spinal condition that included an extra lumbar vertebrae fused to the sacrum. The rarity of the condition, combined with the fact that so many people in one spot had it, indicates a significant level of inbreeding.

Another excavation at a cemetery in the Peruvian capital of Lima found that at least some pre-Incan people from the Lima Culture (which flourished from A.D. 400 to 1200) also practiced incest. Six women found buried alongside an elite man — who were presumably some of his wives — were inbred to the point of suffering from painful hip and spine deformities.

Ancient Zoroastrians

In the ancient world, much as in many societies today, incest was generally seen as a serious taboo that violated both cultural rules and religious laws. But, amongst the Zoroastrians of ancient Iran, the practice of marrying close family members was sometimes enshrined as a religious ideal that came to be known as xwedodah. Iranian texts from the 9th and 10th centuries came out especially strongly in favor of xwedodah, though it's not clear how often Zoroastrians back then were really marrying their parents or siblings.

Writers from the era certainly took their time to paint a rosy picture of the ideal intertwined family. Some argued that related parents would love their children more, get along better with one another, and — like so many other groups before and after have believed — would keep their bloodlines supposedly pure. Outsiders who wrote about xwedodah indicated that it was more likely to be practiced by families of elites in Zoroastrian communities, such as priests. However, it's possible that members of lower classes might have taken part in the practice, as well.

These sorts of marriages have even worked their way into folktales from the region, which have a higher-than-average incidence of consanguineous marriages in the stories, as per a statistical analysis published in Community Genetics. Though Iran is now majority Muslim and Islam generally frowns upon most forms of consanguineous marriage, first-cousin marriages are still traditionally considered to be acceptable in some Iranian communities today.

House of Braganza

Lest you think all of the European royal inbreeding was kept to the Spanish Habsburgs or the descendants of Victoria of England, look to Portugal's House of Braganza. Research published in a 2018 issue of the American Journal of Human Biology concluded that, of the 17 known marriages involving members of the dynasty, eight pairs were equivalent to those of second-cousin marriages or closer. These included one marriage between first cousins and an uncle-niece union. Moreover, researchers found that the Braganza lifespan was noticeably shorter compared to the rest of the population.

One of the most eye-catching examples of what the House of Braganza wrought by all the inbreeding could be Maria I of Portugal, the first queen to rule Portugal in her own right. Because the genetic intricacies of the Braganzas aren't as closely studied as those of the Habsburgs, we can't say for sure that her troubles were due to inbreeding. But Maria, who was the one who married her uncle, did have issues that might be linked to her tangled family tree. She appeared to suffer from manic and depressive episodes accompanied by psychosis, which might garner her a diagnosis of bipolar disorder today. Then again, she had an especially stressful life that saw the deaths of her husband and oldest son, the violent French Revolution, and the looming power of Napoleon Bonaparte. When Napoleon invaded Portugal in late 1807, Maria and her family fled the country for Brazil, where she died in 1816.

Neanderthals

Though the last known Neanderthals died out about 40,000 years ago, we know a fair amount about these close human relatives thanks in part to genetics. Take the case of one Neanderthal woman who lived in the Altai Mountains of Siberia, as per a 2013 study published in Nature. Genetic material taken from her 50,000-year-old toe bone showed that her parents were likely half-siblings. Her DNA hints at quite a few more instances of inbreeding in the family line and indicates that Neanderthals, Denisovans (another close relative), and anatomically modern humans were already interbreeding at this point — maybe bringing in much-needed genetic diversity.

But why would Neanderthals be so inbred? It's not as if they were building great dynastic alliances across Ice Age Europe and Asia, as far as anyone can tell. The available evidence indicates that Neanderthals lived in relatively isolated groups that tended to be relatively small. In fact, that may have been the issue. With so few nearby partners to choose from, Neanderthals may have found themselves facing a dating lineup that consisted mostly of cousins and other, even closer relatives.

A 2019 paper in PLoS One suggests that this could have led to a decrease in the reproductive fitness of the generations that followed, leaving Neanderthal communities with sinking population numbers. They would have also been more vulnerable to genetic issues and may not have faced environmental stressors with as much resilience as the more genetically diverse modern humans that eventually took over their territory.

Maria Antonia of Austria

Charles II of Spain may be one of the notoriously inbred members of the Spanish Habsburg dynasty, but the most inbred title more rightfully goes to his niece, Maria Antonia of Austria (also known as Marie Antoine of Habsburg). According to an analysis in Heredity, she has the highest known inbreeding coefficient (a measure of how inbred someone is) in the whole family. For Maria, it exceeds the inbreeding coefficient of someone born of a parent-child union or to full siblings. More specifically, Maria's father (Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I) was both her mother Margaret Theresa's uncle and first cousin. Margaret Theresa was seriously inbred herself. Some have even speculated that she died young in childbirth because of a genetically weakened system.

Perhaps that's also why Maria Antonia was the couple's only surviving child, though the lack of good postpartum and pediatric care in the 17th century certainly wasn't an asset, either. Yet, Maria Antonia seemed relatively unaffected by her mixed-up genetic legacy. She was once slated to marry her own uncle, Charles II, but the marriage was reportedly nixed because he was 12, she was 6, and the family needed heirs more quickly than a couple of school-aged kids could manage. It likely didn't help that Charles may have already been obviously affected by his own inbreeding. Instead, Maria Antonia married ruler of Bavaria Maximilian II and produced a handful of heirs before dying of birth complications in December 1692, at only 23 years old.