The People Who Caught Some Of The World's Most Dangerous Serial Killers

The public has had a morbid fascination with serial killers since before that term was even coined. We human beings tend to look for explanations in the unexplainable, and for most of us, there is nothing harder to comprehend than the mindset of those who would stalk and kill other human beings, often just for the thrills. The literal book on the subject was written by FBI agent Robert Ressler, who — with his partner John Douglas — became the first profilers, conducting the kind of research and interviewing the kinds of individuals that would drive most law enforcement types to an early retirement. Thanks to those two (who were the inspiration for the lead characters in the acclaimed Netflix series "Mindhunter"), the investigators who followed in their footsteps have been able to put some of the most dangerous people on the planet behind bars.

This profession is, as one might imagine, not an easy one in any sense of the word. The investigators we'll be looking at today have sacrificed time with their families, peaceful sleep, and their mental health in the interest of keeping the streets safer, and we owe them all a debt of gratitude. Fair warning: we'll be getting into some pretty dark territory here, so proceed with caution.

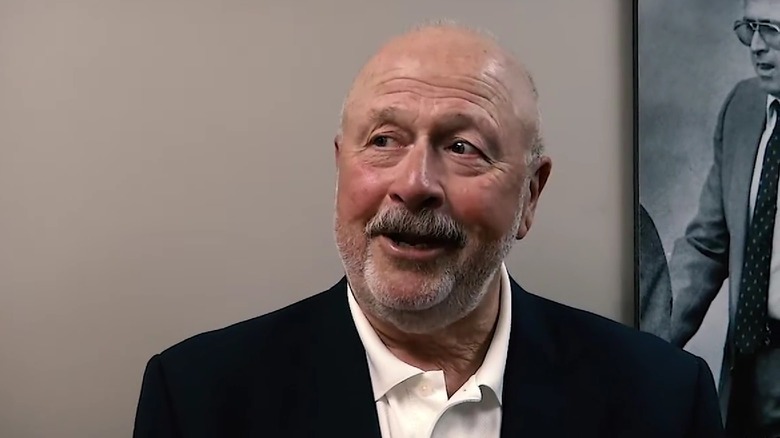

Paul Holes

On the day before his 2018 retirement, Contra Costa County, California, cold case investigator Paul Holes nearly played out a scene from every Hollywood movie involving serial killers. Alone, with no backup, he drove to the house of the man he was sure had committed a shocking string of burglaries, rapes, and murders between 1975 and 1986 — the man the press and police had termed the "Golden State Killer," whose rampage had covered hundreds of miles and dozens of victims. Holes would later tell NPR that his training overrode his desire to look his quarry in the face: "In hindsight, this was foolish from an officer safety standpoint," he said. "Fortunately I didn't go up to the door."

As it turned out, though, he was on the money. After doggedly pursuing leads and building a profile of the killer for decades, Holes had zeroed in on Joseph DeAngelo, a former police officer who had used his own training to elude law enforcement during his reign of terror. DeAngelo had often attacked couples in their homes in well-to-do neighborhoods. "The psychology of this offender was very different than the typical serial rapist," Holes related. "This was a much bolder and more brazen offender." DeAngelo became the first known serial murderer to be positively identified through genealogy, which compares DNA left at crime scenes to that submitted to public databases by family members. In 2020, the 74-year old DeAngelo pleaded guilty to 13 murders, and received a sentence of life in prison without the possibility of parole.

Ken Landwehr

Dennis Rader, the BTK Killer — an acronym for "Bind, Torture, Kill" — was the epitome of the cold, calculating, intelligent serial murderer. Between 1974 and 1991, he killed at least 10 victims in WIchita, Kansas, communicating with the police through taunting letters and even phone calls. He then fell dormant, but in 2004 — seemingly simply out of boredom — he began taunting the cops again, sending correspondence which contained clues to his identity and basically sticking his tongue out at law enforcement. Fortunately, there was one detective on the case who knew just how to appeal to Rader's vanity and inflated sense of self. Ken Landwehr, who had been part of a task force aimed at apprehending Rader since 1984 and had commanded the Wichita homicide unit since 1992, would earn his own nickname from the press and his peers: the "Dick Tracy of Wichita."

When Rader resumed his correspondence with the cops, Landwehr used press conferences and newspaper ads to open up his own line of communication. Through these means, Rader asked Landwehr if it would be safe for him to send information via computer floppy disk, and Landwehr assured him it was. Of course, it was not — metadata on the disk revealed the first name of the user (Dennis) and where the data had been created (Christ Lutheran Church, whose council Rader was president of). The cops arrested Rader shortly thereafter, and when he asked Landwehr why he had lied, the commander's answer was elegant in its simplicity: "Because I was trying to catch you" (via The Washington Examiner). Rader received 10 consecutive life sentences; Landwehr, unfortunately, passed away in 2014.

Frank Salerno

If you were a serial murderer in the '70s or '80s, the very thought of Los Angeles Sheriff's Department detective Frank Salerno on your tail might have been enough to make you rethink your activities. In 1977, Salerno headed up the task force assigned to apprehend the Hillside Strangler, who sexually assaulted, tortured, and killed 10 young women in just a few short months, dumping them in the hills outside L.A. It was Salerno who came to the conclusion that the killer was, in actuality, two men — cousins Angelo Buono Jr. and Kenneth Bianchi, who both caught life sentences for their crimes.

Then years later, Salerno — along with his partner Gil Carrillo — were tasked with tracking down an arguably even more terrifying killer: Richard Ramirez, the "Night Stalker," who murdered at least 14 people in 1984 and 1985. Relentlessly pursued by Salerno and Carrillo's team, Ramirez left L.A. for San Francisco, where his brutal M.O. of terrorizing victims in their homes quickly connected him to his previous crimes. After leaving behind key evidence — including a partial footprint and a fingerprint in an abandoned car — Ramirez was apprehended in August 1985. He was tried and sentenced to death in 1989, and died of lymphoma on death row in 2013.

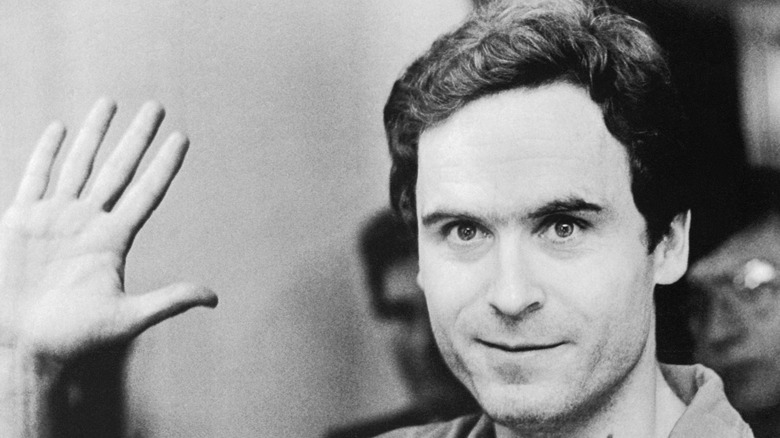

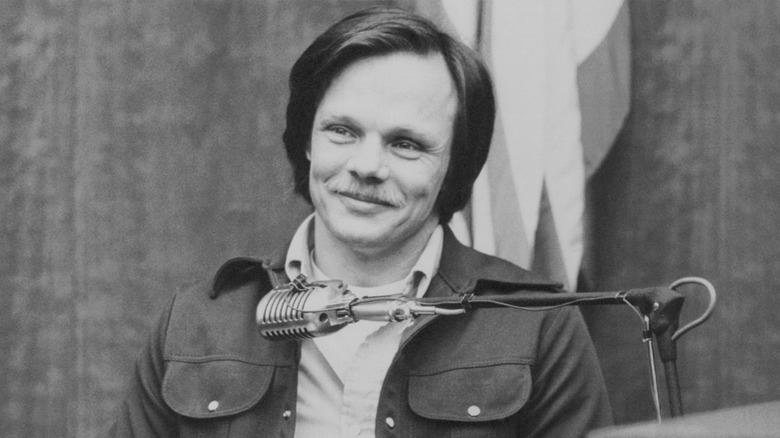

Robert Keppel

Investigators don't come much more respected than Robert Keppel, whose career as a green homicide detective in King County, Washington in the mid-'70s began with an assignment to a series of crimes that would eventually be tied to perhaps the most infamous serial killer in American history. Digging into the disappearances of two young women from a State Park in 1974, Keppel — working with a serious dearth of clues — was able to use motor vehicle records to whittle down his list of suspects to a short one that included a man by the name of Ted Bundy (pictured above), who, of course, would years later be executed for the murders of dozens of women.

As chief investigator of the Criminal Division of the Washington Attorney General's Office — a division which today is named after him — Keppel created the computer database known as HITS, the Homicide Investigation Tracking System, which has helped to bring untold numbers of violent offenders to justice. He consulted on the Atlanta Child Murders case, and assisted the task force assigned to snare the Green River Killer, Gary Ridgway — and such is the level of respect he commanded that Bundy himself, impressed with his doggedness, reached out to Keppel to discuss his crimes for Keppel's book "Signature Killers." Keppel passed away in 2021 at the age of 76, but his legacy in the annals of criminal justice is nothing short of immortal.

Joseph Kozenczak

In 1978, Des Plaines, Illinois chief of detectives Joseph Kozenczak was investigating disppearances of several young men and boys in the area when he caught a break in the case that a lesser investigator might have overlooked. Following the disappearance of 15-year old Rob Piest from a drugstore, witnesses told Kozenczak's team that he may have gone to see a local contractor by the name of John Wayne Gacy about a summer job. Focusing their investigation on Gacy, Kozenczak himself had plucked several items from the man's trash — including a receipt from that very drugstore. When the boy's mother remembered that her son's friend had left behind just such as receipt in the pocket of his jacket, Kozenczak realized in a flash that Gacy was indeed their man — and that he was now in possession of evidence that Piest had been at Gacy's house.

Knowing that he needed more, the investigator employed a campaign of psychological intimidation against Gacy, tasking teams of cops with conspicuously surveilling him around the clock for days on end. Sure enough, after less than a week of this, Gacy began to crack — and, after being presented with the receipt along with other evidence, plus the word of a witness who claimed Gacy had admitted to murdering dozens of boys, he soon confessed to his crimes. Jurors did not buy his insanity plea, and Gacy was sentenced to death — a sentence which was carried out by lethal injection in 1994.

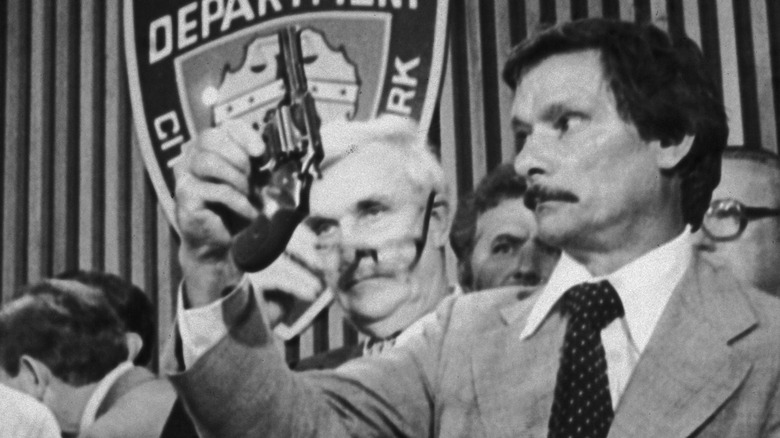

Edward Zigo

The late '70s in New York City were by all accounts rather tense, with high crime rates and sweltering summers adding to a sense of general unease in the Big Apple. Exploiting this unease in explosive fashion in 1976 and '77 was a man who made his presence felt with a .44 revolver: David Berkowitz, the "Son of Sam," who killed seven people, mostly young women, and injured seven more before being apprehended. Berkowitz was a predator who fancied himself too smart for the cops to catch, taunting them with a series of letters and employing disguises such as wigs to throw them off of his scent — but he didn't count on one detective, Edward Zigo, whose gut was more than a match for Berkowitz's wiliness.

Berkowitz was arrested essentially on a hunch from Zigo, who noted the small detail that the man's car had been ticketed for being illegally parked in Brooklyn on the night of a shooting in that borough. Upon searching his car (with no warrant), detectives found a rifle, maps that marked the Son of Sam's previous crimes, and most damningly of all, an unsent letter in the same blocky script the killer used in his previous correspondence. While investigators waitied for the warrant to show up, Berkowitz exited his apartment with his .44 revolver in a paper bag — and promptly announced, "Well, you got me. How come it took you such a long time?"

Charles Moose

In early October 2002, Washington, D.C., Maryland, and Virginia were rocked by a series of shootings that were terrifying in their unpredictability. Over several weeks, 10 people were killed and three more injured by shots fired from a considerable distance by someone wielding a high-powered rifle; the locations of the attacks were seemingly random, and police were initially stymied by conflicting descriptions of the shooter's vehicle. But in the midst of the terror wrought by the shootings and demands for answers from a public on the verge of panic, one man led the investigation into the attacks in a calm, deliberate manner that encouraged investigators to effectively assess what few leads they had — Montgomery County Police Chief Charles Moose.

Under Moose's leadership, investigators diligently pieced together enough evidence — which included, unbelievably, a cryptic phone call from the killers themselves to a priest in Ashland, Virginia — to allow them to focus on Lee Boyd Malvo, a teenage Jamaican immigrant, and Persian Gulf War veteran John Muhammad. Moose's team was able to arrest the pair before Muhammad's plan, later related by Malvo to investigators, could come to full fruition: he had intended to use the random shootings to extort money from the government, which he would use to recruit more underage shooters nationwide with the aim of unleashing chaos and terror upon the entire country. Malvo eventually received a life sentence, while Muhammad was executed by lethal injection in 2009.

James Wardwell

Thought to be the most prolific serial murderer in the history of Connecticut, drifter William Devlin Howell was imprisoned in 2007 on a 15-year sentence for manslaughter in the death of a 33-year old woman, Nilsa Arizmendi. Despite pleading guilty as part of a deal, Howell later tried to change his plea, insisting he was innocent — but New Britain Police Chief James Wardwell knew better. Howell had a nagging feeling about the swampy area behind a shopping center where Arizmendi's remains had been found. "I kept on going back, bringing back our investigators to search again and again," Wardwell would later tell Vice. "We were never satisfied that all the remains were found." When a hunter found what appeared to be a human skull in the area, recovery efforts began in earnest — and they turned up the remains of three additional missing people.

That discovery led the cops to dig deeper, and before it was all said and done, the remains of seven total people had been recovered from the area. Having already been convicted on the single count of manslaughter, Howell pleaded guilty to six additional counts of murder, resulting in six consecutive life sentences — all thanks to Wardwell and his team, whose efforts ensured that he will never walk free again.

Brian Jarvis

Chester, Florida police officer Brian Jarvis probably never expected that his computer skills would make him a legend, but such are the unexpected twists and turns of law enforcement. While working as a lead detective on the case of an assailant who was murdering truck drivers in the area in the late '80s and early '90s, Jarvis wrote a program that parsed out common threads among multiple leads in an investigation — a program which, when fed data pertaining to his current case, kept returning with the name of Aileen Wuornos, a sometime prostitute and drifter. Focusing their investigation on Wuornos, the cops were eventually able to gather enough evidence to arrest her and charge her with the murders of seven men, each of whom had been shot multiple times with a small-caliber firearm.

Wuornos, of course, became one of the most notorious serial killers in American history, and one of the first women known to fit that description. Her case has been the subject of endless think pieces, documentaries, and even a 2003 feature film — "Monster," in which Wuornos was portrayed by Charlize Theron, who took home a Best Actress Oscar for the role. Jarvis fielded calls from reporters and true crime TV shows right up until his 2008 retirement due to his role in the investigation; Wuornos was executed in 2002.

Paul Bynum

For five months in 1979, Lawrence Bittaker (pictured above) and Roy Norris terrorized the Los Angeles area with a series of extraoridinarily cruel crimes. The two, acquaintances from their respective stints in prison, prowled the coast in a van looking for teenage girls to victimize — and after plucking their young targets off the streets, they subjected them to degradation, sexual assault, and torture with implements such as wire hangers and sledgehammers before killing them and dumping their bodies. The "Tool Box Killers" were apprehended thanks in part to the efforts of lead investigator Paul Bynum of the Hermosa Beach Police Department — but the effort took a terrible toll.

At trial in 1981, Bittaker was sentenced to death, and Norris to life in prison — but in 1987, Bynum died by suicide. When Norris was denied parole in 2009, the prosecutor on his case, Stephen Kay, told the Daily Breeze that Bynum's suicide note expressed fear that the two would one day get out of prison, and seek revenge on him and his family. Kay called Bittaker and Norris the two vilest criminals he has ever come across — and this is a man who was involved with the trials of Charles Manson and his murderous "family."

Gary Thatcher

With the exception of the unusually high-profile case of JonBenet Ramsey, Boulder, Colorado is not exactly known for unexplained murders. Between 2003 and 2009, though, a series of mysterious missing persons cases were stumping police detectives, who did not initially connect them all. Eventually, they would be tied to one man: Scott Lee Kimball, a convicted fraudster and former FBI informant who was already serving a lengthy sentence as a habitual criminal.

Three of Kimball's victims were girlfriends of acquaintances from his time in prison due to fraud-related activities, and the fourth was his own uncle, Terry Kimball, all of whom were likely killed in the interest of covering up further criminal schemes. Lafayette, Colorado police detective Gary Thatcher, who specialized in fraud investigations, was among the first to connect the dots between the most recent and earlier disappearances after interviewing several of Kimball's associates. After getting into contact with the FBI, Thatcher theorized that Kimball was feeding agents bogus information about his own criminal activities — and that in addition to being a prolific white collar criminal, Kimball appeared to also be a serial murderer, as the extent of his associations with the missing parties came into focus. Armed with enough evidence to convict Kimball as a habitual fraudster, Thatcher and his team arrested him in 2007, and in 2009, he was charged with four counts of murder, eventually receiving a 70-year sentence.

Pat Postiglione

In 1990, Fort Worth, Texas native Paul Dennis Reid was paroled after serving seven years of a 20-year sentence for armed robbery. After relocating to Nashville, Tennessee — reportedly to pursue a career as a country musician — he laid low for awhile before graduating to much, much more serious crimes. In the spring of 1997, Reid was responsible for a rampage in which at least seven people, all employees of fast food restaurants, were gruesomely murdered in the waning hours of the evening — a reign of terror that had restaurants locking their doors and sending their workers home early, for fear that the "Fast Food Killer" could strike again.

The case was cracked by legendary homicide detective Pat Postiglione, who has served as lead detective on well over 100 homicide cases, and who called Reid's case the most memorable of his career in an interview with WKRN.com. "The whole city was on edge for months," he said. "We went literally nonstop ... It was very stressful and a tough time." Reid was connected to the crimes in June 1997 after attempting to kidnap the manager of a Shoney's restaurant where he had previously worked; he was sentenced to death, but died of an undisclosed illness in 2013 at the age of 55.