What You Didn't Know About JFK's Life As A Writer

That John F. Kennedy was not the brother initially marked down as a future president is a well-known part of his story. Joseph Kennedy Sr. had groomed his oldest son, Joseph Jr., for a political career, an ambition the younger Joe shared according to the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum. But the younger Joe's death in World War II shifted those expectations onto John. Up until then, the often-sickly younger brother had to worry about his health, though that didn't stop him from being an outgoing, popular, and slightly lazy student. For his own career, John entertained dreams of becoming a writer.

Those literary ambitions never went away, even as Kennedy took up the mantle of politics and climbed his way to the White House. Indeed, the two goals became intertwined; Kennedy's book on principled U.S. senators, "Profiles in Courage," first published in 1956, helped elevate his reputation. But "Profiles in Courage" owed a great deal to Kennedy's aide Theodore Sorensen; Craig Fehrman claimed in Politico that Sorensen did most of the work. And that book only reflects a part of Kennedy's literary legacy.

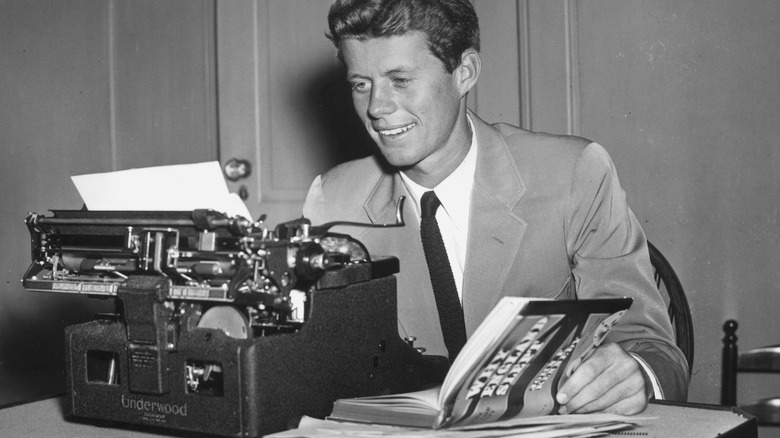

His Harvard thesis became his first book

From childhood, John F. Kennedy was an avid reader. The National Parks Service names "King Arthur and His Knights of the Round Table" and "Billy Whiskers Kids" as among his favorite books. English and history were the only school subjects Kennedy gave his full effort to while at Choate. His grades remained average when he went to Harvard, but he did impress tutors like Bruce Hopper. "His preparation may be spotty, but his general ability should bolster him up," Hopper wrote of his student (per Michael O'Brien's "John F. Kennedy: A Biography"). "A commendable fellow."

At the time Kennedy was in school, his father was serving as ambassador to the United Kingdom, and Kennedy visited him on summer holidays. Britain's appeasement of Nazi Germany was a hot issue, and Joseph Kennedy Sr. supported the policy. His son felt otherwise. In 1940, when World War II was underway, he decided to write his senior thesis on Britain's failed strategy towards Germany. He went against both his father's attitude and popular explanations for the failure, and he stressed the sacrifices called for by democratic systems of government.

The thesis, originally titled "Appeasement at Munich," was graded magna cum laude Kennedy thought he could expand it into a book and eagerly did so, with his father's encouragement. Joe Sr. even recruited columnist Arthur Krock to help edit the manuscript. Krock proposed a new title, "Why England Slept," and the book became a bestseller.

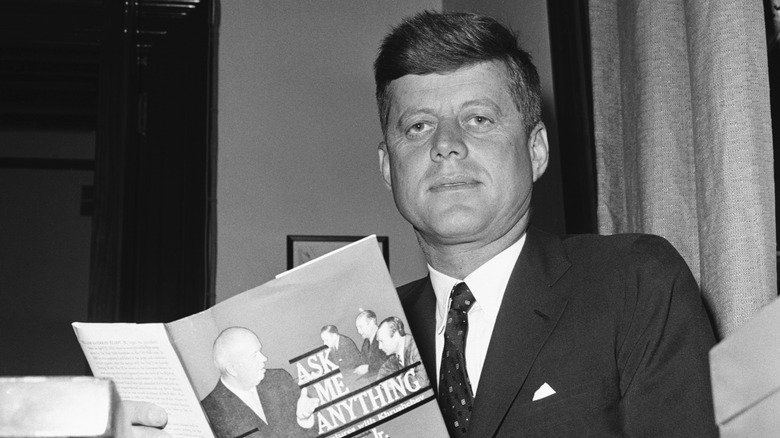

How much of Profiles in Courage did Kennedy write?

Describing his involvement in "Why England Slept," columnist Arthur Krock said, "I may have supplied some of the material ... but it is [John F. Kennedy's] book" (per Michael O'Brien's "John F. Kennedy"). Kennedy was extremely proud of his reputation as a writer. His family said that he counted his 1957 Pulitzer Prize for "Profiles in Courage" as his greatest honor, and he once said that he would rather have won the Pulitzer than the Presidency.

But almost as soon as he won the prize, it became a controversy. Politicians often use ghostwriters to produce readable books, but winning a Pulitzer for a ghostwritten book was another matter. A few reporters criticized Kennedy on those grounds, culminating in a discussion on "The Mike Wallace Show" that moved the Kennedy family to threaten a lawsuit. Kennedy furiously defended his claims to authorship, and Theodore Sorensen, who'd ghostwritten articles for Kennedy, supported those claims. Only toward the end of his life did Sorensen acknowledge that, in addition to research, he had written most of the first draft. And Jaqueline Kennedy's teacher, Jules Davids, also had a hand in the book according to The New York Times.

Critics like Craig Fehrman have used such revelations to downplay Kennedy's contributions; Fehrman even denied him credit for the concept and structure. But biographer Fredrik Logevall has argued that, while Kennedy undeniably received help in drafting the book, he set its themes and put in the work.

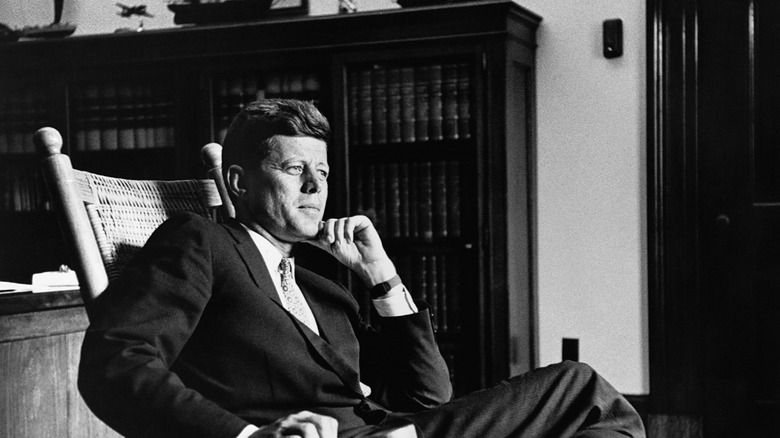

His final book was for the Anti-Defamation League

John F. Kennedy's last book, "A Nation of Immigrants," began as an essay written while he was still serving in the Senate. It was done at the request of Ben Epstein, the one-time leader of the Anti-Defamation League. Per the ADL, Epstein wanted Kennedy to provide an outline of what immigration reform could look like to counter a rising trend in xenophobic rhetoric. The essay, published by the ADL in 1958, discussed successive waves of immigration and the value that immigrants brought to the United States. It also pushed for an end to a quota system that discriminated against migrants who weren't from Western Europe.

Kennedy was not in favor of open borders and unlimited immigration, but he was an outspoken advocate for reform. It was among his high legislative priorities as president. Ahead of a planned push for an immigration bill, Kennedy decided in 1963 to revise "A Nation of Immigrants" into a book.

According to Tom Gjelten's "A Nation of Nations," the revised "A Nation of Immigrants" was ghostwritten for Kennedy by his aide Myer Feldman. Feldman and others coupled advocacy for immigration reform with civil rights reform to persuade Lyndon B. Johnson to see the Immigration and Naturalization Act over the finish line. Also helping to make the case was the book version of "A Nation of Immigrants," which was only published after Kennedy's assassination.