Why Refrigerators Were So Dangerous In The Edwardian Era

Of all the conveniences of modern life refrigeration has to be among the most appreciated. It's hard to imagine a kitchen without one, or our diets without a refrigerator making fresh meat and produce so easy to keep. And yet the fridge as a common household feature didn't come about until the early 1900s according to the BBC.

It's not that people didn't appreciate the value of cold in preserving food before then. Per "The Secret Life of Machines" (via YouTube), our ancestors found all sorts of ways to keep things cool, from evaporating water under earthenware pots to harvesting ice and snow during the winter and trapping its cold air with wood and straw. By the Victorian era, many homes had some form of icebox, a hardwood cabinet with a tin or zinc lining and insulation. The top shelf held a block of ice usually purchased from the local ice man while the lower shelves held food and collected water (per The Vintage Fridge Company).

Experiments with artificial refrigeration go back to the 1700s, but the basics of the modern fridge's vapor compression system came about through Carl von Linden's work in 1876 (per ThoughtCo). These early fridges operated through the use of ammonia, sulfur dioxide, and other toxic gases. The gases could and did leak out of their less-than-airtight containers, sometimes killing unsuspecting kitchen dwellers.

Fatal accidents inspired Albert Einstein to fix the fridge

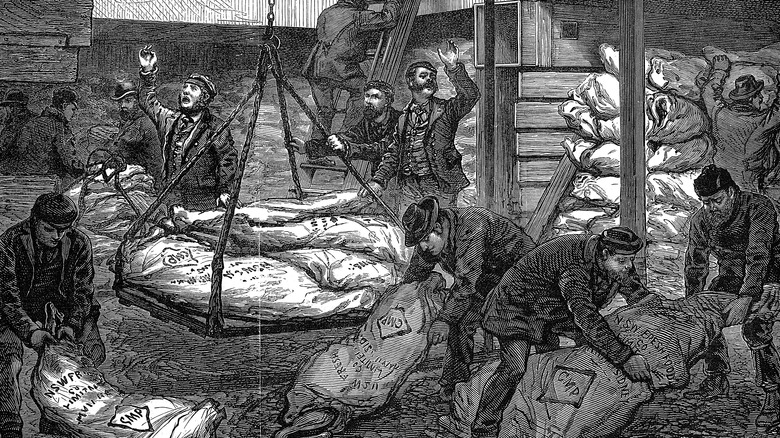

The way a modern refrigerator works is relatively simple. By compressing gas into a liquid and circulating it through the machine, a fridge removes heat from its inside and brings it down below room temperature (per the Department of Energy). According to "The Secret Life of Machines," the first practical experiment with such a system was by an Australian brewery company looking to serve cold beer. As the technology developed, printing presses, hospitals, and factories all sought refrigeration (per Darment), and factories devoted to making ice started appearing in Victorian Britain.

The problem was that the gases available at the time were all either toxic, flammable, or both. And early refrigeration systems tended to leak. This created a noxious stench around them and increased the risk of fire or suffocation. Homeowners, who could first start buying refrigerators in the Edwardian era, could easily be killed, and in the 1920s, that's exactly what happened in a series of accidents.

A fatal mishap with a fridge in Germany during this time caught the eye of Albert Einstein. In his tongue-in-cheek history book "Einstein's Refrigerator And Other Stories From the Flip Side of History," Steve Silverman writes that a horrified Einstein collaborated with Leo Szilard to try and design a nonmechanical fridge less subject to breakdown. They secured a patent and worked with a German manufacturer to make their new fridge, but by the time it was ready for production, it was already obsolete.

Freon saved the fridge (and hurt the ozone)

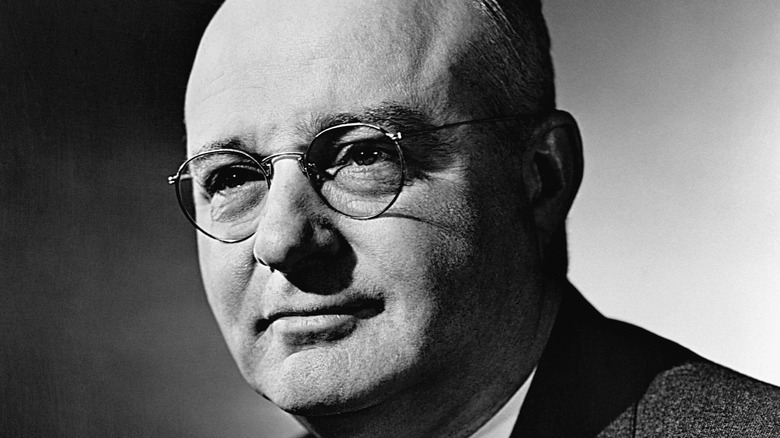

Albert Einstein's proposed solution to the problems with refrigerators was an electromagnetic pump. Per Steve Silverman's "Einstein's Refrigerator," liquid metal moved through the fridge via wires wrapped around a steel container. But around the same time, the chemist Thomas Midgley thought that he could improve the existing vapor compression technology by substituting an odorless, nontoxic, nonflammable gas for ammonia and the other coolants that had been in use since the Victorian era. The only question was what to use instead.

The answer, at least at first, was freon, the brand name of dichlorodifluoromethane. Midgley developed it at GM in 1930 (per History). People outside of his team were slow to appreciate freon as a superior coolant, but while accepting the Perkin Medal for his work with gasoline, Midgley decided to do a little unorthodox advertising. At the black-tie affair, writes Joe Schwarcz in "Radar, Hula Hoops, and Playful Pigs: 67 Digestible Commentaries on the Fascinating Chemistry of Everyday Life," Midgley sucked in some freon and blew out a candle with it, proving it was safe around the lungs and fire.

What Midgley didn't know, and no one would until the 1970s, was that freon and other chlorofluorocarbons broke down the ozone layer, leading to the Montreal Protocol of 1987, new coolants, and new methods of refrigeration. As for Einstein's design, it may never have caught on in the home market, but it did influence the cooling system used in certain nuclear reactors.