Famed Occultist Aleister Crowley's Secret Life As A World War I Spy

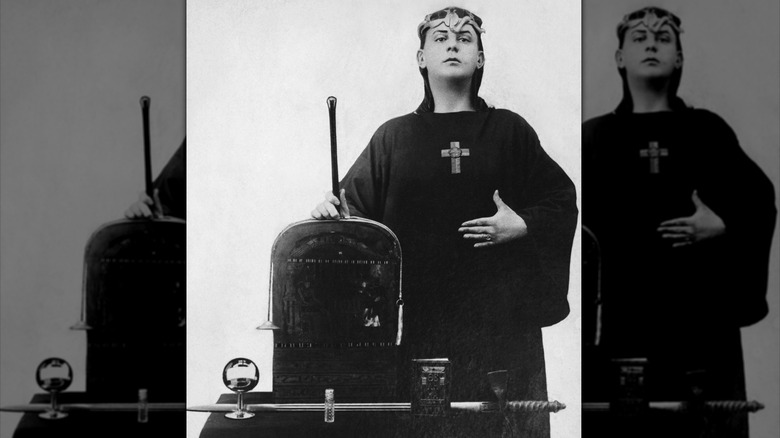

Without a doubt, Edward Alexander "Aleister" Crowley was one of the most notorious, lionized, despised, and idolized occultists and mystics of the 20th century. Born to an evangelical preacher father in 1875 in Warwickshire, England, the ever-enigmatic Crowley was a living, indecipherable Rubik's cube who embodied occult philosophy. Throughout his life he shifted forms again and again, joining the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, dubbing himself "The Great Beast 666," indulging in sex magic and Tantric yoga, studying Buddhism and I Ching, becoming a world-class mountaineer, influencing Scientology founder L. Ron Hubbard, founding the mystical, ritual magic-filled practice of Thelema, and much more. He even, as it turns out, worked for British intelligence — at least in some still-not-perfectly-understood capacity.

It might seem odd for a person so deeply immersed in the occult — i.e., what's hidden from sight — to be so over-the-top, attention-grabbing, and publicly garish. But this, too, was part of the ruse, and part of occultism's historical tether to charlatanism, showmanship, and pageantry; we see this today even in stage magicians. As Wondrium Daily quotes Crowley, "Investigation of spiritualism makes a capital-training ground for secret service work; one soon gets up to all the tricks." Indeed, both spycraft and magical practice involve delving into what's concealed from sight in secret worlds layered within our own. In the end, evidence points to British intelligence plying Crowley to infiltrate secret societies, derail Irish nationalism, and even lure the United States into World War I.

[Featured image by Unknown Author via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled]

Separating fact from fiction

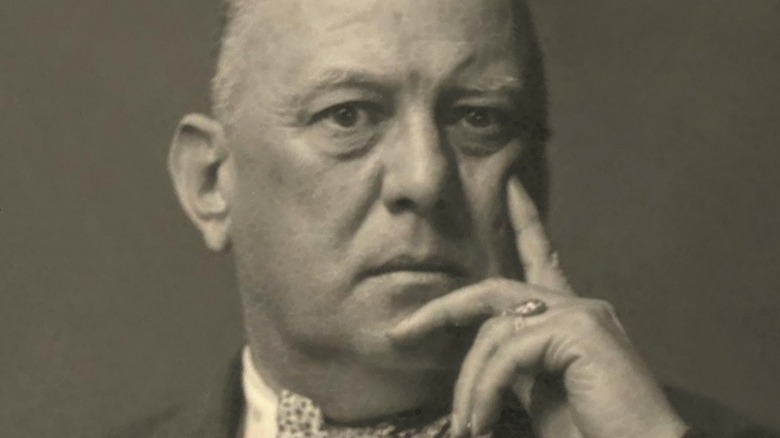

Because Aleister Crowley's involvement in British intelligence dealings comes from a mishmash of fragmented documentation, dubious self-reporting, hearsay, inference, and deduction, little can be confirmed with 100% certainty. After all, we're talking about intelligence operations, to say nothing of the chameleonic Crowley. On top of that, Crowley was prone to grandiose self-inflation and embellished statements, like many occultists and performers. That being said, we can be sure of two things: 1) Crowley was an actual occultist and not just an intelligence asset whose cover was "magician," and 2) He was definitely not James Bond meets Saruman.

While the truth of Crowley's multifarious dealings has been the subject of decades of speculation, much of the recent recontextualization of his life as a spy comes to via Richard Spence's 2008 book, "Secret Agent 666: Aleister Crowley, British Intelligence and the Occult." Spence followed this publication up with an article on Dazed, and years prior in 2000 wrote an ultra-dense academic article of the same name in the International Journal of Intelligence and Counterintelligence. And that Wondrium Daily article we cited before? That was also written by Spence, a professor emeritus at the University of Idaho who teaches entire courses on the occult and secret societies on The Great Courses.

No matter how well-versed, however, it's risky to blindly trust information from a single source. On AMFM Magazine, Crowley scholar Tobias Churton says the "basic narrative" of the whole Crowley story "might be flawed" and "remains something of a hypothesis."

Destabilizing the Irish Republican Brotherhood

As Richard Spence writes in Wondrium Daily, Aleister Crowley's life as an on-again, off-again spy started when he joined the British-born Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn (HOGD) in 1898, a mystical secret society that attracted occultists and artists. HOGD had connections to the Irish Republican Brotherhood, an Irish nationalist movement that wanted Irish independence from England and often employed violent methods. On Wondrium Daily Spence suggests that Crowley was the perfect "agent provocateur" — a rabble-rouser who provokes people into doing illegal acts — to discredit the brotherhood. Tobias Churton on AMFM Magazine, meanwhile, describes Crowley not as a "paid agent," but an "asset," i.e. an informant for agents.

And so it was in October 1914 — three months after World War I started — that Crowley traveled to the U.S. and worked his way into pro-Irish groups by lying about having Irish ancestry, per Spence's 2000 article "Secret Agent 666." After a brash Irish flag-waving demonstration in New York Harbor, The New York Times called Crowley "the leader of Irish hope." Crowley then wrote an open letter declaring the Irish to be "the noble descendants of ancient Egypt and Atlantis." These kinds of patently absurd acts "suited British interests" because they undermined the seriousness of Irish separatism. In his 1929 "autohagiographical" book "Confessions," though, Crowley claimed that he did all of this independently after being rejected by British intelligence.

Riling up pro-German factions

As if Aleister Crowley's goings-on couldn't get more tangled, it's possible that his involvement with Irish separatists might have been a deliberate stepping stone to worm into pro-German groups in the U.S. According to Richard Spence's "Secret Agent 666" article, the aforementioned Irish flag-waving demonstration happened in front of German sailors, who cheered because Ireland and Germany had a mutual World War I enemy in England.

This act might have strengthened Crowley's relationship with German intelligence-related Theodor Reuss, founder of the German chapter of Ordo Templi Orientis (OTO), another occult society that Crowley had joined in 1912. This is why Spence says German-American poet George Sylvester Viereck co-opted Crowley to write anti-British articles for the pro-German magazine, The Fatherland. In the University of Idaho news archive Spence says that Crowley's writing for the magazine was an "over-the-top parody of saber-rattling German militarism."

Come 1915, Crowley said that he "gradually got the Germans to believe that arrogance and violence were the best policy," per Wondrium Daily. He also said that Americans "were like children; easily frightened and responsive to firmness." This might have been the plan from the beginning, though. Despite Crowley saying that British intelligence had rejected his help, U.S. Department of Justice inquiries indicated that "the British government was fully aware of the fact that Crowley was connected with this German propaganda," per Spence's article "Secret Agent 666." Furthermore and wildly, those inquiries said that "Aleister Crowley was a employee of the British Government."

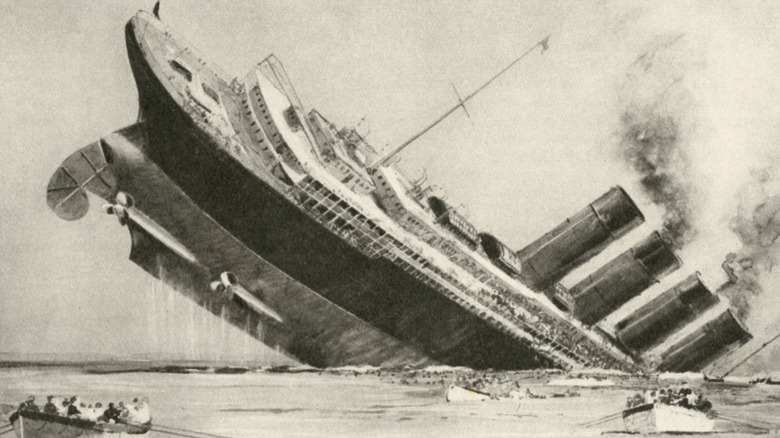

Bringing the U.S. into World War I

And so we get to the most unbelievable excerpt of this short chapter of Aleister Crowley's long and colorful life: The notion that his spy dealings are what maneuvered the U.S. into joining World War I. The U.S. joined World War I following outrage at the German sinking of the passenger boat Lusitania in 1915 as it headed from New York to Liverpool. In the version that takes Crowley into account, Crowley's inveiglement with Irish nationalists and pro-German factions in the U.S. served to foment antagonism between German-Americans and other Americans to the point where the American public grew outraged enough to propel the U.S. into the war.

On the University of Idaho, Richard Spence says that Crowley's actions — whether directly sanctioned by British intelligence or not — "followed precisely the wishes of Admiral Hall, chief of British Naval Intelligence." As the professor emeritus notes, "When push came to shove, Crowley had a visceral loyalty to England." This assertion lends credence to the belief that Crowley was faking it when he set Ireland against England and composed pro-war writings for the German newspaper The Fatherland.

The story gains further credence when taking into account the secret U.S. military "WWI-era file" that Spence claims to have found in 1999. On Dazed he said that the file plainly stated that Crowley "was an employee of the British Government on official business of which the British Consul, New York City, has full cognizance."

Trickster, occultist, and spy master?

So what are we to make of Aleister Crowley's World War I-era British intelligence dealings? Was he a legit spy or enthusiastic, patriotic amateur? Parts of his spy story seem completely plausible, like the very British Crowley acting within pro-German circles to ultimately undermine the German war effort. Other parts stretch believability, like the extent to which Crowley actually impacted the emergence of the U.S. into World War I.

While "occult trickster turned spymaster" is a description that Crowley himself definitely would have loved to hear, ultimately Crowley researcher Tobias Churton on AMFM Magazine might have the most realistic conclusion about the matter. He reports finding a World War I-era letter from British intelligence operative Everard Feilding regarding Crowley's "ludicrous pro-German propaganda." In it, Churton says Feilding "makes it categorically clear that while eccentric, Crowley was indeed trying to assist British intelligence." And that's that.

Evidence suggests, though, that Crowley's intelligence dealings didn't stop with World War I. According to Churton, Crowley moved from Paris to Berlin from 1930 to 1932 after Parisian newspapers accused him of being a spy. In Berlin, Crowley reportedly met the head of the Special Branch of British intelligence — Lieutenant Colonel John Fillis Carré Carter — on a regular basis to inform him about Nazi dealings. Crowley fled the country in 1932, he said, because the Nazis were on to him. And just to add a dash of typically dubious Crowley flair to the proceedings, Churton said Crowley even gave "magical training" to the future head of MI6.

[Featured image by Aleister Crowley via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled]