Why Did The US Enter WWI?

The United States joined the First World War for several reasons, after enduring a prolonged period of German aggression. While many people commonly believe that the sinking of the Lusitania in 1915 was the key cause — in reality, it was just one contributing factor and didn't actually spark the war itself.

The push for peace would continue for some time before the U.S. finally folded. As the National WWI Museum and Memorial points out, it should be remembered that President Woodrow Wilson campaigned for re-election in 1916 on an anti-war platform — making any moves toward a war footing potentially controversial for his administration. He could not discount the fact that many people in the U.S. have German roots, giving America good reason to maintain a neutral stance in the early days of the war.

Nonetheless, the Central Powers did their best (i.e. their worst) to aggravate the U.S., and subsequently made American involvement an inevitability. Attacks on shipping were a PR disaster for Germany, and in the end, the Central Powers became so nervous about potential American involvement, they opted for some foolish pre-emptive measures which ultimately forced Wilson's hand.

Germany's wild unpopularity

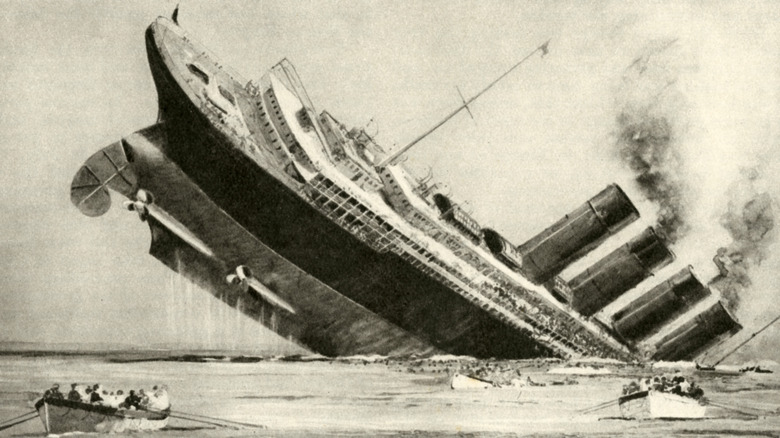

It is possible to imagine a parallel reality in which the U.S. never took sides in the hugely messy European war. However, Germany did its very best to test American patience by committing a host of war crimes at sea. The most famous of these was the sinking of the Lusitania, a British passenger liner that was headed for New York. Over a thousand people died in the unprovoked torpedo attack, including 128 Americans. The sinking was widely regarded as an act of barbarism in the U.S. and led to immediate calls for retribution.

Despite the potentially disastrous diplomatic consequences for Germany, the British passenger ship the S.S. Arabic was attacked in the same manner just a few months later. Finally, U.S-American relations neared a breaking point when the Germans hit another civilian vessel, the French ship the Sussex, in early 1916. Yet — for now — the U.S. did nothing. Instead, President Woodrow Wilson secured an agreement with Germany — the Sussex Pledge — to end unrestricted attacks on shipping and thus preserve the peace.

The pledge held good until January 1917, when Germany decided to throw caution to the wind. Kaiser Wilhelm II and his cabinet became so convinced that they could beat Britain at sea, they resumed their trigger-happy submarine activity, enraging the already hostile U.S. The situation reached a knife edge, and the U.S. cut diplomatic ties and began to arm their merchant ships.

A little push from Great Britain

By the Spring of 1917, the U.S. was a hair's breadth away from attacking Germany when Britain pushed them over the edge by handing the American government a shocking piece of intelligence. British spies had been intercepting and decrypting German communications for some time, and by 1917 their code breakers could read most of them. Keen to get the U.S. on their side, the British ambassador handed the Americans the so-called Zimmerman Telegram, on the 24th of February, hoping it would spur them into action.

The message was sent in anticipation of a possible U.S. declaration of war and it proposed an alliance with Japan and Mexico. The extraordinary letter asked the Mexican government to side with Germany against the U.S. in the event of a war and encouraged them to invade Texas, Mexico, and Arizona.

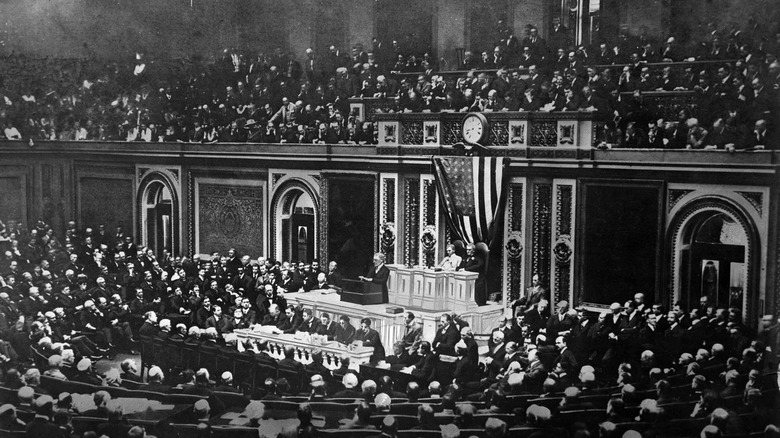

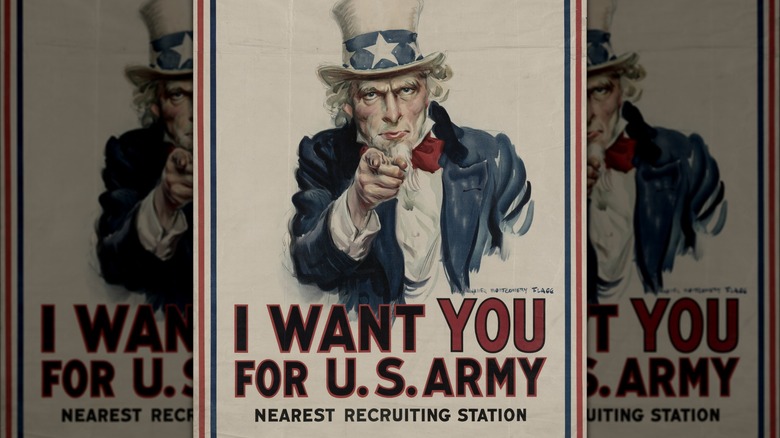

When the letter became public knowledge, peace was no longer an option and America's fate was sealed. German Foreign Minister Arthur Zimmerman himself confirmed the authenticity of the telegram on March 29th. By April 6th, 1917 both the U.S. Senate and House agreed to declare war on Germany, per The Library of Congress, and troops were officially in the trenches in France in October.