Who Is Job From The Bible?

On September 17, 1967, Charlie Brown had one of his more unusual humiliations on the baseball mound. Behind on runs, as usual, he complained to Schroeder and asked why the team had to suffer so. Schroeder quoted the Book of Job at him, prompting Linus, Lucy, and all the rest to stop the game for a lengthy discussion on the nature of pain and the meaning of Job. As the talk went on, Charlie Brown broke the fourth wall to complain, "I don't have a ball team ... I have a theological seminary!"

He might have benefitted from joining the debate. As a well-meaning guy perpetually done in by misfortune, Charlie Brown had at least a little in common with Job, the man who would not renounce God no matter what horrors befell him. His book, included in the Ketuvim ("Writings") section of the Bible, is among the most celebrated for its prose and poetry and most discussed for its content. Its answerless depiction of the issue of theodicy — justifying why an all-knowing, all-loving, all-powerful God permits evil to strike the righteous — has been debated by rabbis, priests, and laypeople for longer, and in greater depth, than poor Charlie Brown's baseball team could hope to fit in a Sunday comic.

[Featured image by Luca Giordano via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled]

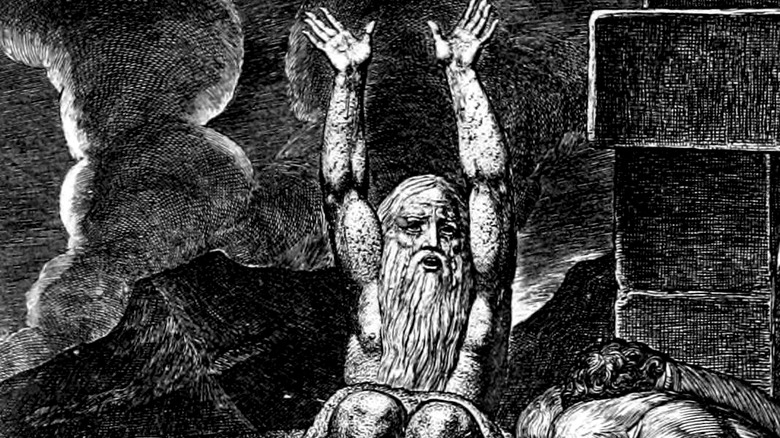

Job was tested by God and Satan

At the beginning of the Book of Job, Job himself was a prosperous man of unimpeachable character. The prologue (via BibleGateway) declares: "He was the greatest man among all the people in the East." Job may not have been an Israelite. According to The New Yorker, his name isn't Jewish and his genealogy isn't recorded, but he still praised God and offered regular sacrifices — not only for himself but for his many happy children.

When God approvingly noted Job's devotion to a group of angels, one of them doubted the depth of Job's faith. The angel in question was Satan — sometimes translated as the "Accuser" or "Adversary" — though he was not the all-evil being we've come to know since. "Stretch out your hand and strike everything he has," Satan told God, "and he will surely curse you to your face." God answered by letting Satan do as he would with Job, short of taking his life. In one horrible day, Job's flocks, servants, and children were all killed. Though wracked with grief, his first instinct was to fall in prayer. The famous line "the Lord giveth, and the Lord taketh away" comes from his praise of God in that moment.

Confronted with this show of faith, Satan next afflicted Job with sores and pestilence. His own wife lost patience with him and demanded he renounce God and die, but Job still refused. Neither, however, did he admit to doing anything to deserve such divine punishment.

[Featured image via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled]

The Book of Job is in two parts

After Satan's calamities befell Job, three of his friends came to give him comfort. This marks the end of the prose section of the Book of Job until the very end. For 39 chapters, the text becomes a verse poem in which Job laments his sufferings, his friends try and justify what has happened to him by naming sins he might have committed, and Job defends himself with the truth of his righteousness. He grows angry with his friends for their unsatisfying answers and at the harsh examples of the wicked enjoying good fortune around him — but he never curses God.

It's widely accepted that the poetry of Job and its prose bookends were written separately. The bulk of the poem has been dated to between the 6th and 4th centuries B.C. — with a few later additions — and the bookends seem to have come first, being traced back before the 6th century. The book as we know it may not reflect a complete work, either — scholars, writes Abraham Riesman of Slate, think that some of the poem is out of order, and The New Yorker says the book may have missing passages.

That hasn't stopped the poetry of Job from being a widely celebrated literary achievement. And according to the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, Job was meant as literature, not history. But what is said through that literature about God is at odds with much of the Old Testament.

[Featured image by William Blake via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled]

God gives Job a non-answer

In the lengthy verse section of Job, once Job refuted the condemnation of his friends and vented his anger without blasphemy, a passing young man named Elihu reprimanded them all. He chastised the friends for judging Job despite his doing nothing wrong, and he chastised Job for justifying his own goodness without accounting for God's. Elihu declared God to be beyond the comprehension of man, not to be judged by them.

After Elihu said his piece, God spoke from a whirlwind. He essentially confirmed Elihu's advice by recounting all the wonders of creation and rhetorically asking Job what he would know of them. Job's reply? He said (via BibleGateway): "Surely I spoke of things I did not understand ... therefore I despise myself and repent in dust and ashes." Then, with a return to prose for the epilogue, God praised Job's honesty and condemned his friends for not speaking the truth about the Lord. He ordered them to provide a sacrifice that Job would offer on their behalf, restored Job's good fortune, and blessed him with long life.

The epilogue grants Job a happy ending, but it's been noted by many over the years that neither in the final chapter nor the poetic dialogue between God and Job is it ever explained why the latter suffered in the first place. Nor is the idea of God's ways being unknowable reconciled with teachings elsewhere in the Bible that portray suffering as punishment for sin.

[Featured image by William Blake via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled]

The meaning of Job is heavily debated

The Book of Job has spawned lines that are pervasive throughout the world, and the central character has become a byword for patience. "The patience of Job" is still in use as a common idiom. But the fact is that the book has horrible things happen to a good man on God's say-so without offering any clear or easy answers for why.

For some, the ambiguity is the point. The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops says that the book leaves the question of suffering for readers to answer. The Episcopal reverend Samuel G. Candler of the Cathedral of St. Philip writes that Job isn't a book about God's wisdom for man, but man's dialogue with himself about the facts of suffering and injustice. Many Christians also take Job as a precursor to the lament of Jesus on the cross, an interpretation that religious scholar Mark Larrimore dates to Pope Gregory I.

Others have sought firmer answers from Job, and traditional translations have sometimes been challenged in the search for them. The idea of Job as patience personified may be a translation error — per Christianity.com, "perseverance" may be more accurate. Others, from Elie Wiesel to Edward L. Greenstein, have reinterpreted Job as someone who is defiant in his last words to God, voicing pity for the afflicted of humanity by evil and bitterly refusing to be done in by it.

[Featured image by Gaspare Traversi via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled]