Incredible True Stories Of Black Soldiers In The American Civil War

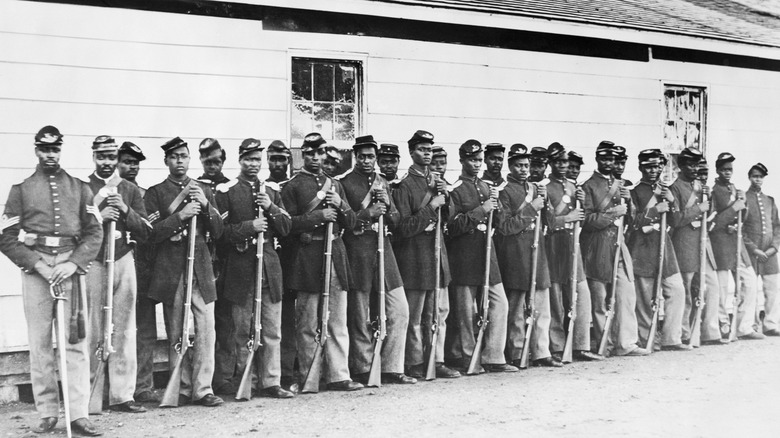

The American Civil War was one of the most tumultuous times in the United States' history. More than 600,000 soldiers died in what is still the country's bloodiest conflict, and there were over 1 million casualties combined between the Union and the Confederacy. Of the more than 2.7 million soldiers who fought for the Union Army, less than 200,000 of them were Black troops, but they made many invaluable contributions.

Fighting on behalf of the millions of enslaved people south of the Union lines, the 178,000 Black soldiers had to endure incredible hardship, and racism, to fight for a country that didn't even legally consider them citizens. Unsurprisingly, Black Americans were barred from serving in combat units in the Confederate Army until the final month of the war, and there is little evidence that any of them ever did. Many enslaved Black Americans were, however, subjected to work as laborers for their Confederate enslavers during the war, being forced to help fight against the cause of their own liberation.

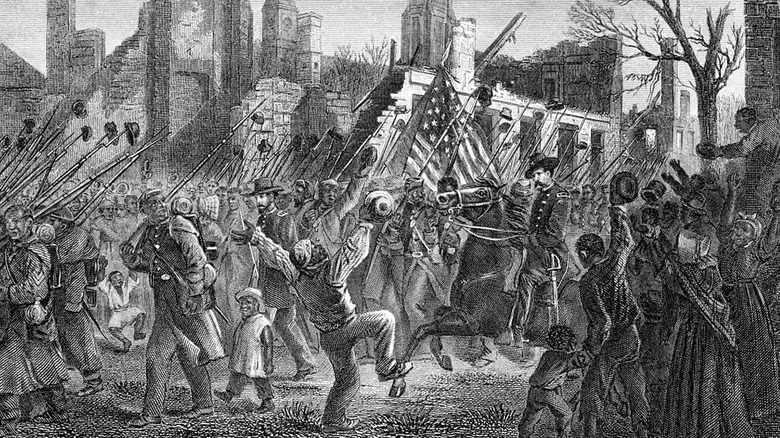

As the war dragged on, Black soldiers became a bigger and bigger part of the Union forces, eventually comprising around 10% of the entire army by the end of the war. Many of them were formerly enslaved and made their way from the Confederacy to the Union to fight against their former enslavers. Black soldiers were some of the most courageous participants of the entire war, and these are a few of their incredible true stories.

William Gould

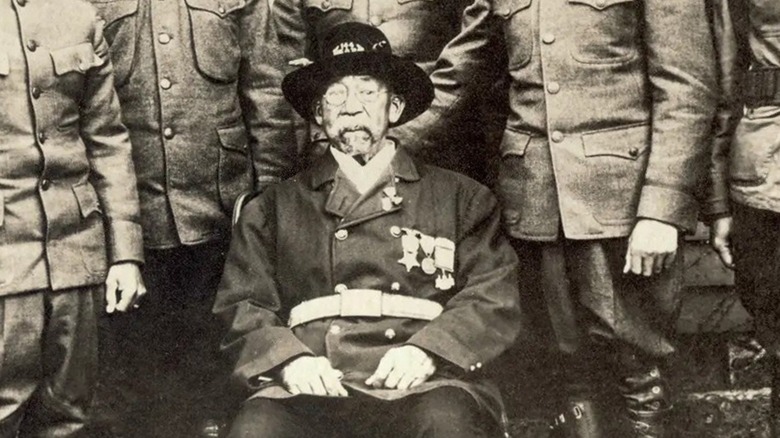

Among Black soldiers who fought in the American Civil War, few have a story as amazing as that of William Gould (pictured seated, with his six sons). Gould was enslaved when the war kicked off in early-1861, and a year later he was still in North Carolina when he made one of the most important decisions of his entire life: to steal a boat and escape from to freedom.

Gould, along with seven other enslaved persons, stole a boat and made their way more than 25 miles to the Atlantic Ocean, where they then came into contact with a Union warship: the USS Cambridge. Free from the Confederacy, his escape preceded the declaration of the Emancipation Proclamation in September 1862 by only one day, and he was legally considered contraband — the term for formerly enslaved persons who made it to the Union. Yet, Gould didn't just take a free ride from Cambridge back to the safety of the North, he instead stayed on and fought with the Navy.

Within the Navy, Gould worked his way up to the rank of landsman and wardroom steward, and later served on the USS Ohio and USS Niagara. Gould kept a memoir of his life as a contraband, which was later published into a book in 2003. Gould survived the war to live nearly 60 more years until 1923, when he passed at the age of 85.

Dr. Alexander Augusta

If you were a Black Union soldier fighting during the Civil War and found yourself injured, you were in some of the best possible hands if Maj. Dr. Alexander Augusta was attending to you. Augusta was a native of Virginia in what would eventually become the Confederacy, though he was never enslaved. Literate, Augusta first moved north and then out west to California, before eventually making his way to Canada.

Augusta returned to the U.S. in 1863 after earning his medical degree in Toronto, where he became the first Black doctor commissioned as a major in U.S. Army history, setting a precedent that would be fulfilled by thousands more in the century and a half since. Yet, Augusta had to struggle just to be allowed to serve in the army, as initially he was denied due to his race and because he had been living in British Canada. It was only after writing to President Abraham Lincoln that the Union Medical Board allowed him to serve and gain his commission. He was soon working with the 7th U.S. Colored Infantry as the only Black surgeon among his colleagues.

Later in the war, Augusta helped oversee the newly created Camp Barker hospital for Black soldiers, and he was also influential in fighting for equal rights for Black soldiers and veterans. August was laid to rest at the Arlington National Ceremony in 1890, the first Black officer to be allowed the honor.

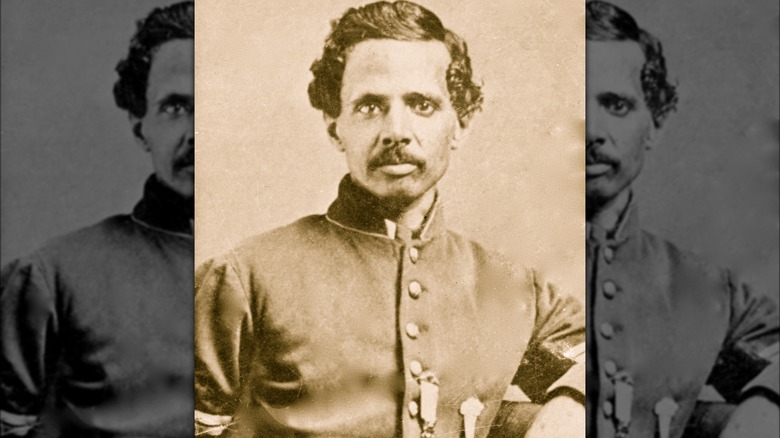

Abraham Galloway

Born in early 1837 in North Carolina, Abraham Galloway had the unfortunate indignity growing up enslaved. He escaped to freedom in 1857 and made his way to Canada and then Haiti, returning to the North once the Civil War broke out in 1861. Galloway joined the Union Army immediately, but he wasn't just any regular soldier: Galloway worked as a spy.

Under the command of Maj. Gen. Benjamin F. Butler, Galloway went throughout the South to gather intelligence, including in his former home state of North Carolina. It must have taken an incredible amount of daring and courage for a formerly enslaved person to actively reconnoiter around the Confederacy, but Galloway was more than up for the challenge. He went even further into the Deep South than he had ever been during his time enslaved, but eventually found himself captured following the first Union attempt to take Vicksburg. Miraculously, Galloway managed to survive his captivity and once again make his way to freedom, resuming his spying briefly for Butler.

Later in the war, Galloway stopped working as a spy and began to focus his efforts elsewhere. He still helped the Union Army by recruiting Black soldiers, and also he fought for Black civil rights and held office in the State Senate of North Carolina after the war. Galloway died in 1870 shortly after his reelection to the Senate at the age of just 33 years old.

Robert Smalls

Robert Smalls' amazing story of escape from Confederate chains to a Union Army uniform is one of the most incredible in history. Smalls was enslaved in South Carolina since his birth, running into trouble as a kid but eventually finding a wife in 1856. Unable to purchase his wife's freedom before the war, Smalls endeavored to find a way to deliver them both being enslaved, and once the Civil War broke out, he found his chance.

Smalls had been working as a crew member on the CSS Planter, a Confederate Warship hemmed in by the Union naval blockade. However, on May 13, 1862, Smalls and the other Black crew members stole the ship when the Confederate crew was asleep onshore, making their way to freedom with stunning ingenuity. Smalls also rescued his wife and kids before making it into the Union blockade, where he and his crew became national heroes. Smalls story would have already been incredible enough if it stopped there, but there is still even more. After entering the Union, Smalls joined the Navy, eventually earning a non-commissioned promotion to the rank of captain and even getting to pilot his own ship, the USS Crusader.

It was no small feat for a Black sailor to get his own ship, and Smalls was the first one to gain the rank of captain. Smalls continued to serve in the Navy and later in the South Carolina legislature, passing away in 1915 from natural causes.

John Lawson

A member of the U.S. Navy during the Civil War, John Lawson was one of just a few Black soldiers to have been awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions. Lawson first joined the Navy in 1863, two years after the war began. Not a lot is known about his early life or why he decided to suddenly join, but for those aboard the USS Hartford, they were sure glad he did.

A year into service, during the Battle for Mobile Bay in August 1864, Lawson displayed an incredible amount of courage and bravery while on the Hartford. In the middle of a massive naval battle, Lawson's ship was hit by an enemy shell, causing serious damage to not only the ship, but also to Lawson himself. Lucky to have not been killed like some of his other crew members, Lawson was badly injured in the leg, but he still kept fighting. Instead of getting his wounds attended to and leaving the deck, Lawson remained at his post until the battle ended.

It was these actions that earned Lawson his Medal of Honor, and he would eventually attain the rank of landsman, which was significant for a Black sailor. Lawson survived through the war into the 20th century, passing away in 1919 at the age of 81.

William H. Carney

Like many other later Black soldiers in the Union Army, William H. Carney was a born enslaved in Virginia. He and his family were fortunate to make their way to the North, and Carney was one of the few enslaved African Americans to be literate. A religious person, Carney felt that joining the Union Army to fight against the Confederacy was a way to serve God, and he enlisted in early-1863.

First a member of the Toussaint Guards, Carney became part of the famous all-Black 54th Massachusetts Regiment. He was in the 54th when they saw their first action at Fort Wagner that July, and it was here that Carney earned himself the Medal of Honor through his heroic actions. Each unit in the army had their own flag bearer, and during the charge the bearer for Carney's went down after becoming wounded. Yet, instead of continuing on, Carney himself picked up the flag — reportedly never letting it touch the ground. Already wounded, Carney displayed immense courage and patriotism by carrying the flag, endearing himself as one of the legends of the already distinguished 54th Massachusetts.

It was not until the 20th century that Carney's actions were finally recognized and he was awarded the Medal of Honor in 1900. Though not the first Black soldier to earn the distinction, his actions are the earliest recorded for a Black recipient. Carney was alive to be awarded the medal, passing away in 1908 at the age of 68.

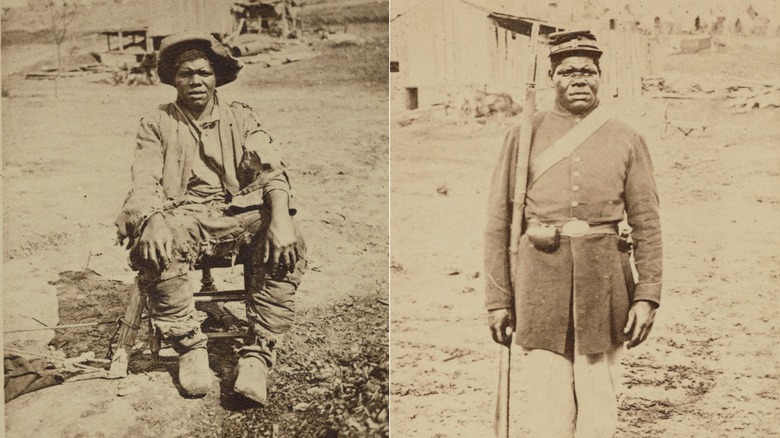

Hubbard Pryor

Of all the stories of escaped former enslaved persons serving in the Union Army, Hubbard Pryor's is perhaps one of the most tragic. Pryor had been enslaved for his entire life in Georgia before he made his way across Union lines in late-1863 to become contraband. He soon joined a unit of the United States Colored Troops in order to take the fight back to the Confederates. A famous before and after photo of him as a contraband and then soldier began circulating, helping boost the Black recruitment effort for the war. However, soon disaster befell him and his entire unit.

Less than a year after escaping from being enslaved, Pryor found himself a prisoner of war under the control of the Confederate Army under Gen. John Bell Hood. Hood horrendously re-enslaved Pryor and his fellow Black soldiers as punishment. Forced to help the Confederacy once again as an enslaved person, Pryor managed to survive through the end of the war, showing incredible personal fortitude and perseverance.

His endurance paid off, and after the war he was allowed once again to live as a free man following the fall of the Confederacy. He later married another formerly enslaved person after the war and they had several children, and he passed away in 1890 in his mid-40s.

Robert Sutton

Robert Sutton's incredible story during the Civil War is one that few enslaved persons could have hoped for, but one that many of them likely dreamed of. Sutton escaped to freedom in the North in 1862 after living the first part of his life enslaved in Florida. Leaving behind a family consisting of a wife and child to make his miraculous escape in a canoe, Sutton did what many other formerly enslaved persons did once entering the Union: He joined the army.

He was in the army when President Abraham Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation went into effect on January 1, 1863, and soon he was sailing towards the Confederacy and his former home. In fact, Sutton was heading directly towards the Alberti plantation which he had previously been enslaved on. Once arriving, Sutton was introduced to the mistress of the plantation, Mrs. Alberti, who was indignant at seeing him now a member of the Union army at her doorstep. Once on the plantation, Sutton showed his fellow Union soldiers the various parts of the land, including the jail for enslaved persons, which horrified them with its brutality.

Many of the Alberti's formerly enslaved people had already left by the time Sutton and the Union made it to the Alberti Plantation, and some of the soldiers wanted to burn it to the ground as revenge. Sutton's story is truly one of the most remarkable of the entire war, and will forever be remembered in the annals of American history.

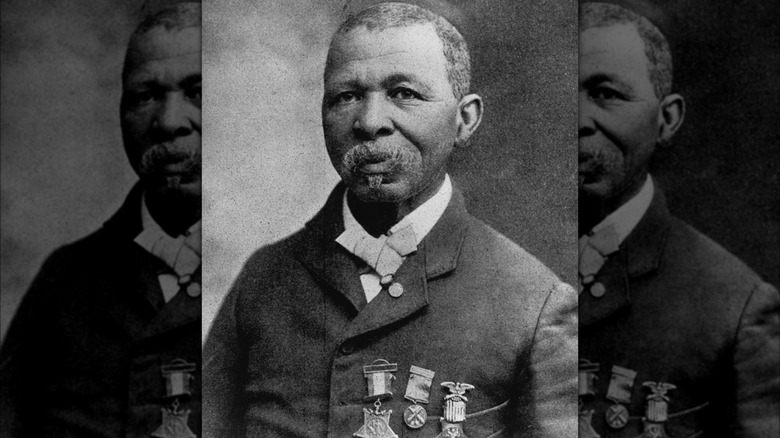

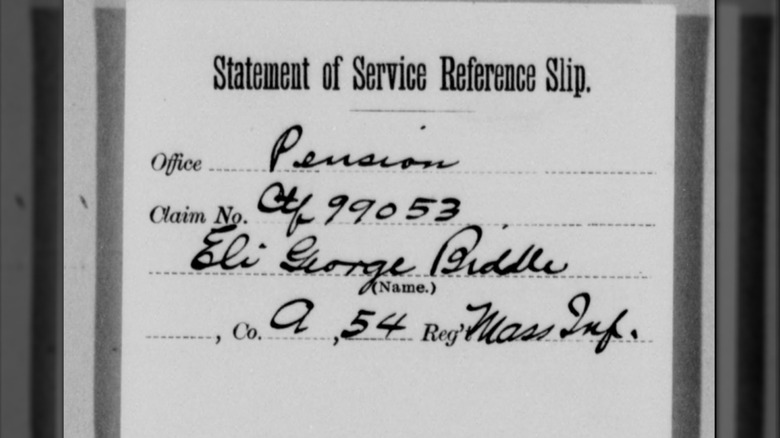

Eli George Biddle

The story of Eli George Biddle in the Civil War is incredibly powerful and illustrious. Biddle was born a free man in Pennsylvania in the mid-1840s, but eventually made his way to Boston as the Civil War was beginning. Still in school at the time, Biddle famously would not sing patriotic songs in class because of the lack of civil rights for Black Americans, which led to his enlistment in the famed all-Black 54th Massachusetts Regiment in 1863.

During the regiment's first action at Fort Wagner that July, Biddle distinguished himself with his incredible actions under fire. Taking part in the attack on the fort as a member of Company A, Biddle actually lost his gun during the assault due to an explosion, but soon realized he had found himself in an even worse predicament. Biddle had missed the retreat of his fellow troops during the battle, and looked up to find himself bereft of allies and surrounded by Confederates. They heard him trying to escape and unleashed an incredible volley of fire towards him, but only managed to hit him in the shoulder, with Biddle reaching the Union lines alive.

Biddle survived after the war for many years, participating in the 75th anniversary of Gettysburg as part of the ceremony, shaking hands with a former Confederate soldier. He did not pass until two years later, in 1940, and was a member of the Grand Army of the Republic after the war.

Andrew Jackson Smith

One of the few Black Medal of Honor recipients from the Civil War, Andrew Jackson Smith was certainly more than deserving of his award. An enslaved Kentucky native, Smith escaped to the North as a teenager in 1862 and began working as a laborer under Maj. John Warner and the 41st Illinois Infantry. This meant Smith would be working against his father, who was his former enslaver and who had joined the Confederate army. Smith was wounded in the head during the Battle of Shiloh, but managed to survive.

Smith then joined the 55th Massachusetts Regiment in 1863, and it was during the Battle of Honey Hill that he earned his Medal of Honor. Similar to the story of fellow Medal of Honor recipient from the 54th Massachusetts William H. Carney, Smith, who was not a designated flag bearer, took the flag from the fallen flag bearer after he was killed. Even though he was wounded, also like Carney, he still held onto the flag and refused to go down.

Unfortunately, it would be more than a century before Smith's contributions were adequately recognized. It was not until 2001 that the army finally awarded Smith his Medal of Honor, 137 years after the battle and almost 70 years after his death. Smith survived through the remainder of the war, and passed away in 1932.

Powhatan Beaty

With a story as unique as his name, Powhatan Beaty was one of the biggest heroes of the American Civil War. Beaty and his family escaped being enslaved in the 1840s, which allowed Beaty the chance to attend school and experience life as a free person. He eventually joined the Union Army in 1863 two years after the war began, quickly becoming a sergeant in a Black Ohio unit that would later turn into the 5th U.S. Colored Infantry Regiment.

He fought at Sandy Swamp and at the Battle of the Crater, but his real heroics came during the Battle at New Market Heights in late-1864. Showing a truly marvelous and commendable amount of courage and gallantry under fire, Beaty risked life and limb to rescue the Union flag from Confederate clutches. In a battle that saw 50% casualties for his division, Beaty ran 600 yards to get the flag and bring it back to friendly lines. If that wasn't enough, Beaty then found himself in charge of his company after the death of his superior officers. He helped turn the tide of the battle to push the Confederates back, earning the Medal of Honor for his actions.

Beaty continued to serve fearlessly until the end of the war, though racism stopped him from gaining the commission he so rightfully deserved. After the war, Beaty returned to his first love of the theater, also taking a bride. He survived until the age of 79, passing away in 1916.