Stories From Egyptian Mythology They Couldn't Teach You In School

It's safe to say that mythology is a popular unit in elementary and middle school classrooms. Heck, many adults are also deeply fascinated by the dramatic tales of powerful ancient gods battling, falling in love, and forming the cosmos. The stories of ancient Egypt are especially well-known, perhaps because of the many striking animal-headed deities in the Egyptian pantheon, and also at least in part because the ancient Egyptian people were so on top of recording things and burying other key bits of evidence with their dead.

But not every myth from this kingdom is ready for the ears and eyes of modern school kids. These tales are thousands of years old and, for quite a few classrooms, also from a land that's thousands of miles away. It's therefore no surprise that what's deemed normal or at least acceptable has changed, sometimes dramatically, over the millennia. Still, try explaining that complex history to an 8-year-old who's just heard the true story of how Horus was born or what exactly creator god Atum did to get all of existence started. Whether there's a certain risqué element involved, a serious dose of moral complexity, or just general eeriness that could detail the entire lesson plan, these are the ancient Egyptian myths they couldn't teach you in school.

Creation involved a lot of spit

Because ancient Egypt encompasses many centuries and quite a few distinct city settlements, the mythology of this time and place gets pretty diverse, too. Even creation myths, which you might think would be pretty standard, varied greatly. Ask someone in Hermopolis, and they might tell you that a group of snake- and frog-headed deities get everything started with a cosmic egg. Others might say that the egg actually came from a semi-divine goose, or that the god Atum arose out of chaos and spat the next couple of gods into existence.

Yes, spit — if you were lucky. Some versions of the Atum creation myth say that he created a son, Shu (god of the air), and a daughter, Tefnut (goddess of moisture), by hocking a presumably pretty large loogie into the increasingly less chaotic void. Other versions get more explicit and claim that Atum engaged in some self-pleasure and produced them in that manner. Either way, the idea is that he gave up or divided some of his vital essences to create the next gods. It's also very definitely an ancient myth that grade school teachers are bound to skip during lesson planning.

Geb and Nut have a very unusual relationship

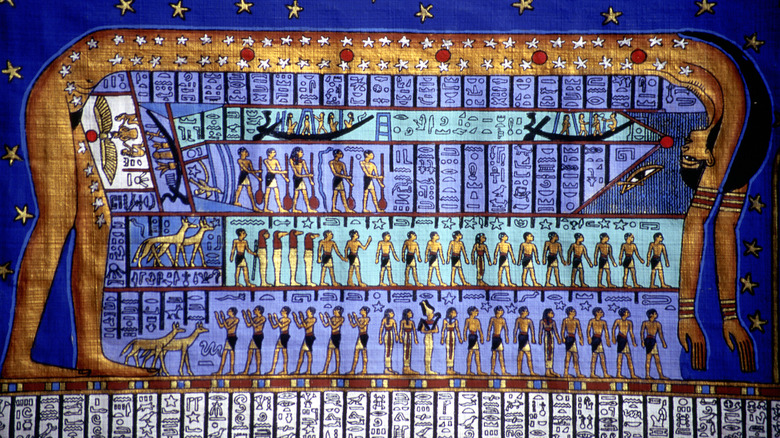

With practically no other options in the roiling, semi-chaotic beginnings of existence, Tefnut and Shu turned to each other. From their union came Nut, the sky goddess, and the earth god Geb. According to the myths of some regions, both were members of the nine-deity group called the Ennead. But that didn't mean everyone got along. Geb and Nut were also apparently very into each other (another reason your teachers may have passed this myth over). They were so enmeshed that sky and earth were right next to each other, making life on the growing plane of creation pretty difficult.

To keep things moving along, Shu intervened and separated his two children. That space between sky and earth became vitally important, creating space for the air that we breathe and allowing celestial bodies like the sun to make their way through the sky unimpeded. It also allowed space for the next round of gods to make their way into existence, including some of the most famous names in the ancient Egyptian pantheon: Isis, Osiris, Seth, and Nephthys, with the falcon-headed Horus sometimes also joining in (but then messing up the nine-god Ennead theme).

Sekhmet is a murder machine

In many ancient Egyptian pantheons, Sekhmet was a terrifying presence. The lion-headed goddess was closely associated with heat, illness, and war, but she also acted as a powerful protector of the pharaohs and a patron deity of doctors. It paid off to keep her happy.

Once, however, humans weren't quite so wise to the nature of the fearsome Sekhmet. Way back in times that were ancient even to the ancient Egyptians, it was said that humanity tried to rebel against the sun god Re, who lives on Earth to rule them. Re takes the uprising poorly. He took his daughter, the love and fertility goddess Hathor, and transformed her into the warlike Sekhmet. She went out and slaughtered the rebels, but her insatiable bloodlust — not to mention the actual rivers and lakes of blood that polluted the land — made even Re step back. Seeing that he had gotten himself and the rest of existence in way over their heads, he directed his people to brew thousands of jars of beer dyed red.

When it was poured over the land, Sekhmet saw it, and thinking the stuff was more of that tasty blood, guzzled it all down. The drunk goddess stumbled home and, when she sobered up, was the peace-loving Hathor again. Re, for his part, decided it was time to rule from the safe distance of another realm and left Earth entirely.

Few teachers want to talk about Khepri

For a certain sort of kid, bugs are pretty cool. But, even for the beetle-obsessed child in your life, digging into the mythology of Khepri may be a bit much.

First, Khepri looks quite weird, or at least he does to many modern people who aren't hip to ancient Egyptian gods and goddesses. See, he's got a giant beetle for a head. Some might be able to cotton to a deity with the head of a friendly cat or an awe-inspiring falcon, but a whole beetle, complete with mandibles and segmented legs, might be a step too far for the Westernized elementary school classroom. Even if the teacher patiently explains that Khepri is meant to represent a sacred scarab beetle that will roll the sun through the sky like his terrestrial cousins do balls of dung ... well, at that point, even seasoned teachers might have lost their control of the classroom.

It's too bad, though, because Khepri deserves our respect. He's one of the key sun gods that arose over Egyptian history, and anyone who keeps the sun moving is kind of a big deal. And just look at the plethora of scarab amulets and other decorations that can be found in Egyptian archaeological sites. Even pharaohs sometimes incorporated Khepri's name into their own, speaking to the ancient people's love for this carapace-headed deity.

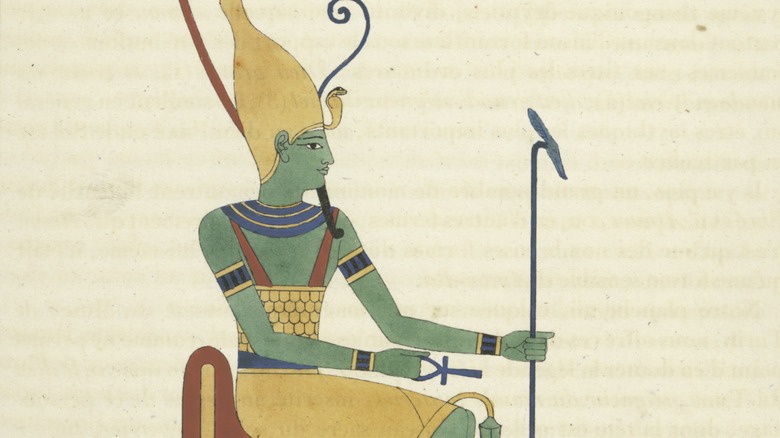

You probably didn't get the full story about Isis

In Egypt, Isis was an immensely popular goddess who could be seen almost everywhere. But there are parts of her core myths that, while they would have seemed normal to the ancients, are often passed over today.

First, there's the matter of her spouse. That would be Osiris, the eventual lord of the dead, who, even while fully alive, was also Isis' brother. That's normal enough for Egyptian gods and royalty millennia ago, though some adaptations of this myth conveniently forget to mention this particular aspect of their relationship.

When their brother Seth gets jealous of the popular Osiris, he tears the other god to bits and scatters his parts across the land, leaving a grieving Isis to reassemble her husband. That episode gets mentioned plenty, but what follows may be edited depending on the audience. Once he's more or less put back together, it's clear that Osiris is missing a key component: his privates. Some versions say that this body part was eaten up by a fish, but whatever happened, the result is that Isis — who's apparently on a quest to conceive a child, dismembered husband notwithstanding — has to figure out a workaround. A model replacement suffices somehow, and she becomes pregnant with her son, Horus. Osiris, who can only be quasi-alive for so long, then makes his way down to the underworld, where he will preside as the ultimate judge of the dead.

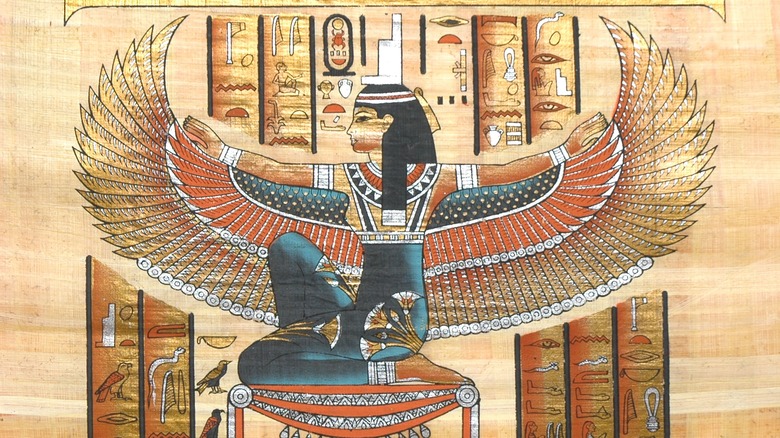

Isis has terrifying scorpion friends

Even if all you know about Isis is that she has Dr. Frankenstein-like powers of resurrection, then it's very clear that she is someone with a tremendous amount of power. But then, as if that weren't enough, there's the fact that some myths claim she also has some utterly terrifying scorpion friends.

One tale maintains that Isis went out into the land accompanied by seven scorpions. She approaches the home of one woman, hoping to rest, but the other woman shuts the door in her face because she's frightened of the goddess's retinue of arachnids. It doesn't help that Isis is looking pretty rough herself and shows up dressed in the tattered clothing of a beggar.

Isis moves on and finds a warmer reception in the hut of a poor woman. But it's not over yet. One of the scorpions returns to the first woman's house and not only administers a deadly sting to her son but also starts a fire that threatens to burn down her house. It also begins to rain, just to make things worse. Isis feels bad, restores the child's life, puts out the fire, and tells the heavens to cut it out — then accepts all of the woman's fine jewelry as an apology. The moral here isn't clear, however, as the other, poorer woman's reward seems to be not having her home burned down or dealing with the terrible effects of scorpion venom.

Horus takes part in an X-rated myth

Few myths outline the differences between ancient Egypt and modern Western culture more starkly than the tale of Horus and Seth. As the uncle of the younger god, Seth was often in opposition to Horus — tearing his father into bits and dooming him to the underworld didn't exactly start things off on a great footing. The incident of Horus' eye, in which Seth stole or damaged his nephew's eye, didn't help things (the eye was restored by either Thoth or Hathor, depending on the text).

But in one myth that is all but impossible to teach to schoolchildren, things get even more shocking. Here, Horus tells his mother, Isis, that Seth is attempting to assault him. To get the upper hand, Horus places some of a very particular bodily fluid of his on lettuce plants in Seth's garden. To the ancient Egyptians, lettuce wasn't just a somewhat flavorless vegetable, but a fertility-boosting aphrodisiac, perhaps because its leaves produce a milky fluid when cut.

Seth wanders by, eats the Horus-infused leaves, and becomes pregnant. Instead of giving birth in the standard way, he produces a sun disk via the crown of his head. Horus claims it and wears the disk as proof that he is the rightful god of the sun who stands in power over the chaotic Seth. No wonder teachers are more likely to skip over this episode and focus on the contest in which the two gods fight as hippopotami.

Isis played chicken with Ra's life

If Isis has the awe-inspiring power to bring life, even from death itself, then it stands that she also has the rather easier power to end it. Well, easy if her target is a standard mortal human. But another god?

Sure, why not? Of course, that's assuming the other god is standing in the way of what she wants. Even Ra, one of the biggest gods of all, wasn't immune from Isis' machinations. In one myth, she decides that she simply must learn the god's sacred name, the knowledge of which will grant her immense power. To achieve her ends, she makes a venomous snake using the drool of the elder god, who is getting on in years.

That snake then bites Ra. Feeling the life leaching out of him, he begs the other gods for help. Isis, feigning surprise at the completely unforeseeable snake incident, has just the power needed to banish the venom. However, she asks a serious price: Ra's true name. This isn't any old name, either, but one that's so secret and powerful no other god has ever heard it. With no other choice but death, he gives it up, and Isis heals him. Now, with the knowledge of the name, she has also achieved her goal of gaining power over all other gods, including Ra himself.

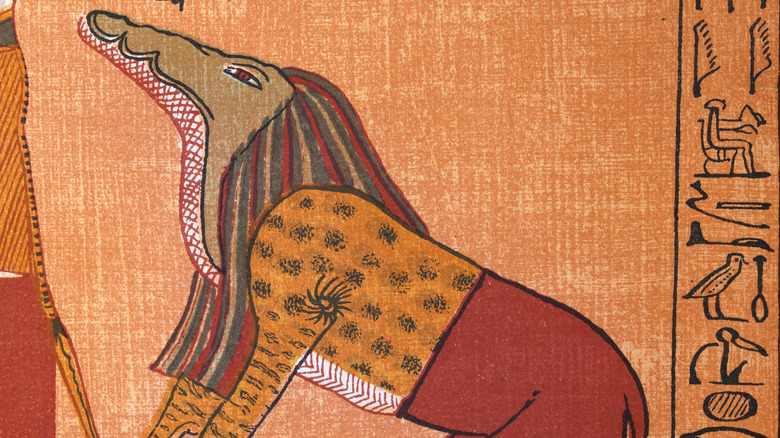

Anubis has questionable parentage

You can't talk about ancient Egypt without discussing mummies. So, of course, there was always going to be a god of mummification. For much of Egyptian history, that deity was the jackal-headed Anubis, who tended to the bodies of the dead and also guided their souls to the final judgment in the underworld. In the earliest depictions of him, Anubis even acted as a judge for the dead until Osiris came in to replace him.

But where exactly did Anubis come from? That gets pretty tricky. In the first appearances of Anubis in Egyptian myth, he just sort of appears as a fully-formed adult god. Later tales make his parentage quite tangled. Some claim that he's the son of the chaotic god Seth and his wife, Nephthys. Others become a real soap drama, with Nephthys becoming so taken with the beauty of Osiris that she not only steps out on her husband but takes on the image of Isis (again, these four are all siblings). Disguised as another goddess, she tricks Osiris into sleeping with her, becomes pregnant, and then ditches the kid in fear of the affair being discovered. Isis does figure it out, in fact, but instead of indulging in some righteous rage, she was said to have adopted the infant god and raised him herself. Some tales go a step further and use this messy incident as the motivation for Seth's later murder of Osiris.

Ammit dooms souls to oblivion via snacking

Egyptian mythology hinges on the afterlife, though the evidence clearly shows the ancient Egyptians loved life, with plenty of artwork, texts, and stories showing that they were ready to seize the day, every day. It was just that preparing for the journey to the afterlife, immediately after one's earthly body gave out, was of key importance. Part of that meant being a decent person while alive. If being good for goodness' sake wasn't enough motivation, perhaps the terrifying demon that stood ready to eat one's soul could give an extra boost.

The supernatural creature in question is Ammit (also known as Ammut), whose name translates to the bone-chilling "Devourer of the Dead." Her other titles — including "Eater of Hearts" and "Great of Death" — make at least part of her purpose pretty darn clear. Ammit is also something to behold, with most depictions showing her with a crocodile's head, a big cat's front, and the hindquarters of a hippo. She stands by as the deceased's heart is weighed on a scale meant to judge whether or not they were good in life. If their heart is too heavy, Ammit gobbles it up and the dead person is out of luck.

Even the ancient Egyptians seem to have been somewhat wary of the devourer, as she never appears to have been worshiped in the same way that other gods were and may have been seen more as a supernatural creature than a full-on deity.

Taweret is terrifying, confusing, and part hippo

Birth in the ancient world was a perilous thing. And while the doctors of ancient Egypt gained renown for their skill, it seems that few put their minds to work addressing the problem of maternal and infant mortality in the kingdom. Many Egyptian women would have been practically on their own, perhaps relying on knowledgeable family or community members who had survived labor. With so few places to turn to for support in a painful and dangerous time, many prayed to the gods. One goddess, in particular, was a favorite of pregnant people and new mothers, though young kids today might be alarmed by her look.

That goddess is none other than Taweret, whose name translates to the feminine form of "the great one." She is depicted with the head and heavily pregnant body of a hippo. Often appearing in amulet form or carved into everyday objects, she also typically sports a crocodile's tail and the limbs of a lion. Like other fearsome gods, her appearance is more or less meant to scare off any of the evils that might befall the pregnant people and young children under her protection. Still, you try explaining that to a sensitive first-grader who's not interested in discussing maternal mortality in the first place.