How The Witch Trial Of Goody Garlick Shook A 17th-Century Town

We've all got one or two (or more) folks in our lives who we just wish would please, please go away forever. Maybe it's a nosy neighbor, a pushy co-worker, a snotty relative, a cocky classmate — take your pick. This is nothing new, and an unavoidable part of human society. Strategies for dealing with such people, however, have changed. Modernly, the internet is the world's grand griping tool into which people vomit all manner of frustrations, calumny, and belittlement through the out-of-fist-range shielding of a computer screen. But maybe things are still better now than before. After all, if you annoyed a neighbor 350 years ago or so, that neighbor could just sigh and say, "You know what? I've had enough of this. You're a witch! You hear that, everyone? She's a witch! Burn her!"

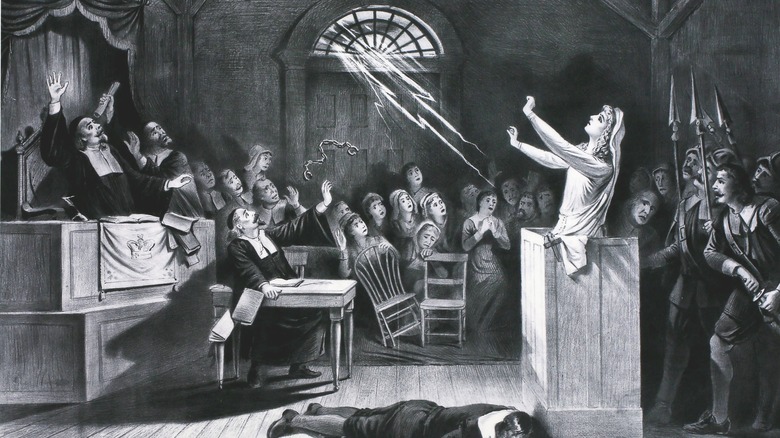

Such was the case with Goody "Goodwife" Garlick, a 17th-century working-class woman in East Hampton, New York. By all accounts Garlick wasn't the most pleasant of people. Dan's Papers calls her "a mean, nasty gossip," while East Hampton historian Hugh King in Smithsonian Magazine takes the demure route and says that she was "a rather obstreperous person." But a witch? East Hampton authorities weren't sure. They listened to testimony against Garlick, including the unverifiable accusations of a 16-year-old mother about "a black thing at the bed's feet" that was supposed to be Garlick. But when Garlick's case got kicked up to Hartford she was acquitted, and no one is completely sure why.

Executed with perfect timing

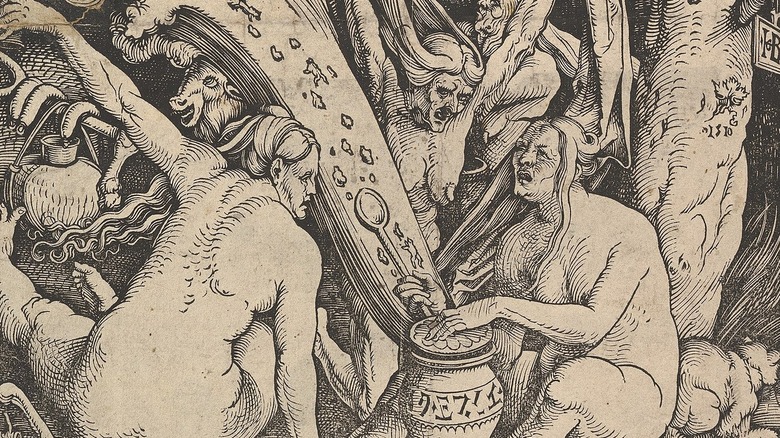

Hunting supposed "witches" had been something of a Catholic fad since the early 1400s, but it really took off starting in 1484 with Pope Innocent VIII's papal bull decrying witchcraft as heresy. Two years later in 1486 German Inquisitor Heinrich Kramer published "Malleus Maleficarum" ("Hammer of Witches"), a "how to" guide for spotting devilry that kicked the witch hunts into high gear. Front to back, "Malleus Maleficarum" contains reams of fantastical scenarios that read like sensational fiction, including forest covens of naked women, sex with demons, and witches summoning hailstorms and dispatching familiars. Kramer's main advice for questioning alleged witches? Torture. There were even honest-to-goodness hunt-for-profit witch hunters roaming Europe and the Americas.

In the burgeoning United States, the witch hunt frenzy reached its zenith at the infamous 1692 Salem witch trials in Salem, Massachusetts, which took place at the end of decades of mounting societal tension. They also happened a full 35 years or so after Goody Garlick's 1658 East Hampton, New York trial. In the years leading up to the trial village opinion of Garlick grew more and more sour. It's possible that jealousy played a role, too, as Garlick's husband Joshua worked for wealthy local landowner Lion Gardiner, as Smithsonian Magazine explains. On top of this, the legal timing worked perfectly. East Hampton had adopted Connecticut colony laws the year prior to Garlick's trial in 1657. And as it turns out, Connecticut courts had a proven track record of executing witches.

[Featured image by Purchase, Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, 1917 via The Metropolitan Museum of Art | Cropped and scaled | CC0 1.0 Universal (CC0 1.0) Public Domain Dedication]

The spell that broke the ox's leg

The allegations brought against Goody Garlick were equal parts typical of the time, insubstantial, and oddly specific. As the Long Island Press cites, people accused Garlick of "cast[ing] evil eyes" — aka, "giving someone some serious stink-eye" — and of sending forth animal familiars to do her bidding. It was also said that a baby once died after Garlick picked it up, which prompts us to ask, "How many babies died that she didn't hold?" or, "How many babies died that other people held?" Dan's Papers also says that people accused Garlick of murdering several others via witchcraft, giving townsperson Goody Simons "fits," causing a pig to give birth "strangely," and making an ox break its leg. Plus, as Smithsonian Magazine says, she "often quarreled with neighbors" — a not-too-irrelevant point to add to the mix.

Most critically, though, it was the claims of 16-year-old Elizabeth Gardiner Howell — daughter of Garlick's husband's wealthy employer Lion Gardiner — that pushed Garlick into the hands of local authorities. Howell took ill in 1658 after giving birth, and while delirious in bed shrieked, "A witch! A witch! Now you are come to torture me because I spoke two or three words against you!" per Smithsonian Magazine. She told her father that she saw "a black thing at the bed's feet" and "a double-tongued woman who pricks me with pins," per the Long Island Press. Then, as reports go, she coughed up a metal pin.

Passing the ball to Hartford

As Dan's Papers says, Lion Gardiner tried to intervene on Goody Garlick's behalf despite his daughter's feverish accusations against the elder woman. Goody Garlick's husband Joshua also tried to speak up to defend his wife. Beyond these two individuals, it seems like Garlick had no one in East Hampton on her side.

As fortune would have it, local East Hampton magistrates weren't too keen to prosecute Garlick. They basically passed the ball to the General Court of Connecticut in Hartford, capital of Connecticut colony, the laws of which had recently been adopted by East Hampton. "The occult doctrine would probably be more safely applied" in that court, the magistrates said, which sounds a whole lot like, "We don't want to be responsible for this."

Garlick got lucky again when her case wound up on the desk of the newly appointed Deputy Governor of the Colony of Connecticut John Winthrop Jr., a prominent public figure who'd helped co-found Massachusetts Bay Colony. Winthrop had just agreed to the job and moved to Hartford in 1657. From here, the commonly told version of the story is that Winthrop was a scientifically-minded person who looked to sociological and historical precedent as causes of accusations of witchcraft. Per Smithsonian Magazine, University of Connecticut professor Walter Woodward says that Winthrop attributed cases of supposed witchcraft to "community pathology," which is essentially when community members feel pressured to act this way or that. Some, though, suggest that Winthrop himself was a practicing occultist.

[Featured image by Kenneth C. Zirkel via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 4.0]

Spared by just the right people

Sites like Long Island Press somewhat inaccurately characterize Goody Garlick as "saved by science" via John Winthrop Jr. While it's true that the Enlightenment — roughly the 17th to 19th centuries — was a time of immense scientific progress, it was more generally a time of shedding former institutions. As a result, the public grew enthralled by esoteric practices, the occult, spiritualism, mesmerism, alchemy, the tarot, astrology — you name it, as IAI News explains. Articles in the Journal of American History, the Isis, the Journal of Interdisciplinary History, and more all describe Winthrop as an alchemist, adherent of the mystical order of Rosicrucianism, and overall metaphysicist.

Of course, there's no way to prove that Winthrop dropped all charges against Goody Garlick because of occult sympathies. Smithsonian Magazine says that Winthrop had connections to Lion Gardiner — East Hampton's wealthy citizen and employer of Garlick's husband — via the Pequot Wars and the establishment of the Connecticut settlement of Saybrook. But regardless, all this discussion is to say: It took a lot of effort and just the right placement of people to save Goody Garlick's life — a life put at risk because of the ire of neighbors.

After the trial, Dan's Papers says that Gardiner recommended that Garlick and her husband not stay in East Hampton. He moved them to his personal plantation, where they worked under his protection. Garlick lived to 100 years old.