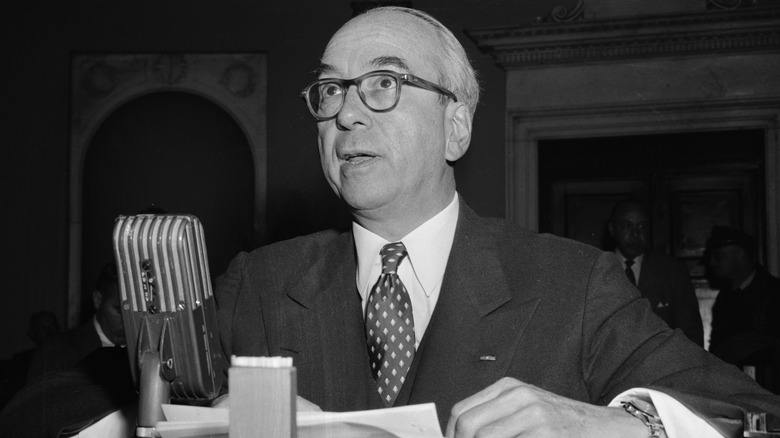

What Happened To Lewis Strauss After The Oppenheimer Hearings?

At the end of Christopher Nolan's "Oppenheimer," Lewis Strauss (Robert Downey Jr.) sees his seemingly assured dreams of being confirmed to the cabinet of the Eisenhower administration dashed when testimony from an upset scientist unmasks the hand Strauss had in destroying the reputation of J. Robert Oppenheimer. In reality, Strauss was always going to be in for a contentious hearing before the Senate. As reported by Time during the proceedings, Strauss had a fierce enemy in the form of New Mexico Senator Clinton P. Anderson. Though his background in banking, naval intelligence, and leadership of the Atomic Energy Commission all pointed to his being a competent choice for commerce secretary, Anderson and others found Strauss an arrogant and suspicious character. They were determined, after President Dwight D. Eisenhower made Strauss acting secretary in a recess appointment, to deny him confirmation by the Senate.

But the role Strauss played in stripping Oppenheimer of his security clearance, and his proselytizing for nuclear weaponry, did alienate him from many American scientists. And the campaign against Oppenheimer, which Strauss deliberately and maliciously waged according to History, did come into play during his confirmation hearings, which ended in a 46 to 49 vote against him. In "Oppenheimer," a furious Strauss still manages to put on a smile when facing reporters after his defeat. The real Strauss would spend the rest of his life nursing grudges while frozen out of government power, but he also racked up several more achievements before his death in 1974.

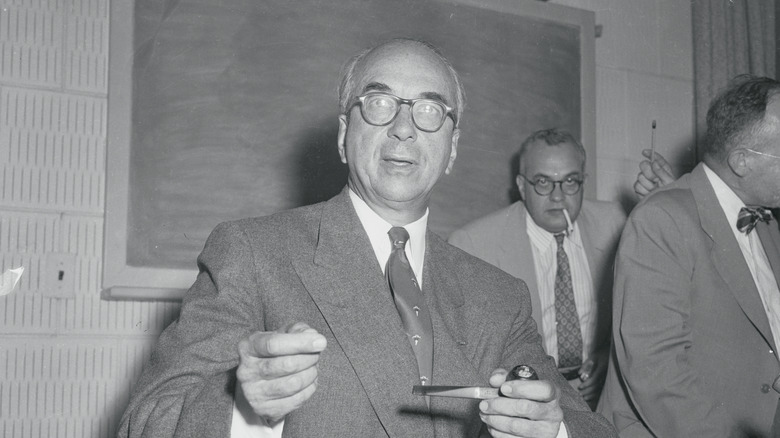

Strauss returned to the private sector

The son of a shoe salesman, Lewis Strauss went into his father's business in 1913 after typhoid kept him from graduating from the University of Virginia (per the UVA Miller Center). From there, he went on to volunteer with Herbert Hoover's U.S. Food Administration, eventually becoming Hoover's secretary. But when he was offered a job as comptroller for the League of Nations, Strauss went into banking instead. By 1929, he was a partner in Kuhn, Loeb & Co. On the side, he taught himself nuclear physics and became a lieutenant commander of the Navy reserve.

World War II saw Strauss active as an intelligence officer, and eventually a rear admiral, and in the immediate postwar period he became involved in U.S. atomic policy. A brief stint as an advisor to the Rockefellers separated his time as a member of the Atomic Energy Commission from his time as its chairman. He rose in Eisenhower's esteem during this time, culminating in his failed nomination to the cabinet.

After that embarrassment, Strauss's time in government and politics was almost entirely done. He briefly re-entered the fray to support Barry Goldwater's 1964 campaign, but most of his energies were devoted to private and charitable causes. Devoutly Jewish, he was involved with the Jewish Theological Seminary and the American Jewish Committee among other organizations (per the Jewish News Bulletin). Closer to home, he managed cattle and corn on his 1500-acre farm.

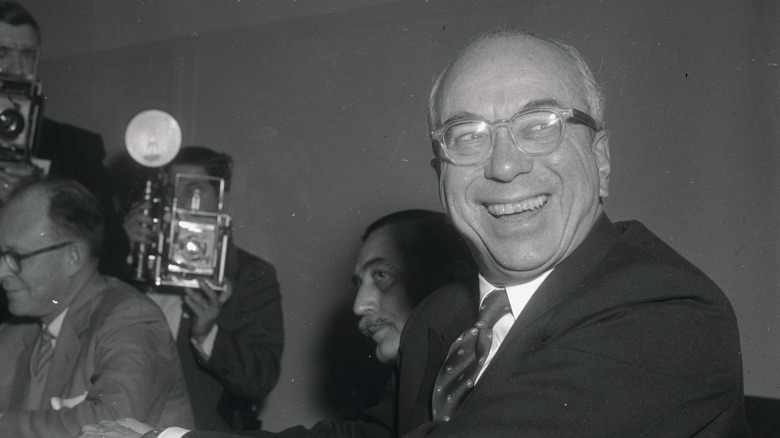

He became an American villain

The U.S. Senate rejected Lewis Strauss for commerce secretary on June 19, 1959. Three years later, Strauss published his memoir, "Men and Decisions." The book, as an early review in Time noted, seemed keen to highlight Strauss's many accomplishments prior to his humiliation. Good deeds discussed included campaigning with Herbert Hoover to feed starving civilians in Germany after World War I and, in an ironic counterpoint to his later advocacy for the hydrogen bomb, Strauss's attempts to dissuade the Truman administration from using atomic weapons on Japan at the end of World War II. Later writers have added to the list Strauss's work to rescue Jewish families from Nazi-controlled Europe (per Mosaic).

But Strauss's virtues, and his willingness to promote himself, have not altered a general perception among historians of the postwar era that he was more villain than hero in American history. In "The Ruin of J. Robert Oppenheimer and the Birth of the Modern Arms Race," historian Priscilla Johnson McMillan paints a common — and convincing — picture of Strauss as a secretive and manipulative individual who exploited atomic policy to suit his own image and target his enemies, including J. Robert Oppenheimer, who McMillian believes Strauss actively colluded in denying security clearance to. Director Christopher Nolan characterized Strauss as the Salieri to Oppenheimer's Mozart for his 2023 film, though actor Robert Downey Jr. was prepared to push for a slightly more heroic perspective (per Vulture).