Messed Up Things That Happened During The Russian Revolution

It probably comes as little surprise that the Russian Revolution was far from the cleanest transitional period in history. Following many difficult years under the Romanov tsars that included slow industrialization and poor showing in international conflict, as well as an earlier revolution in 1905 (which began with the infamous Bloody Sunday massacre), tensions truly boiled over in 1917. The February Revolution — which, confusingly, began on March 8, 1917 — saw Tsar Nicholas II abdicating the throne, and as years of Romanov rule came to an end, a new provisional government took shape, headed by Alexander Kerensky.

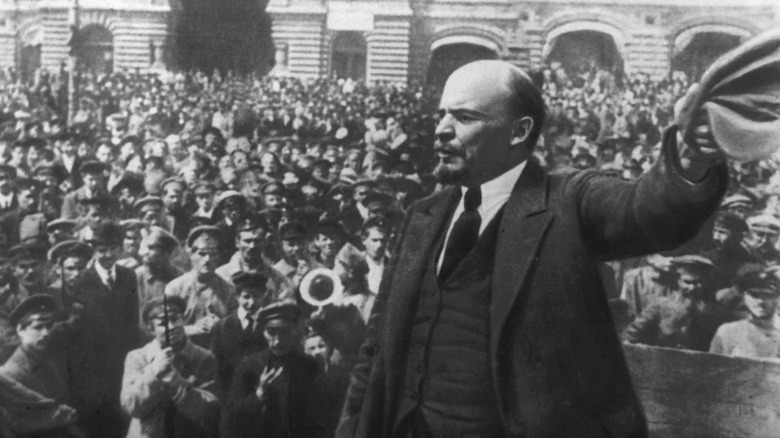

Unfortunately, Kerensky's government was just as ill-fated as the one it succeeded, and as World War I continued to drain Russia's resources, the country found itself prone to yet another revolution: the October Revolution. As Vladimir Lenin returned to Russia from exile, his Bolshevik party took over the government and implemented communism across the country. Of course, the change didn't sit well with everyone, and civil war broke out between the Red forces of the Bolsheviks and a loose array of other factions — ranging from those who still supported the tsar to more moderate socialists — called the White Army. The fighting lasted until 1923, at which point the Soviet Union was established, and the rest was history.

But years of revolution and civil war meant a lot of turmoil, as well as many innocent people caught in the crossfire. In a way, that became the norm, rather than the exception.

The conditions of the Ipatiev House

Following Nicholas II's abdication of the throne, the Romanov family was moved into exile, ultimately ending up in Yekaterinburg at the boarded-up Ipatiev House. In some ways, the atmosphere was as gloomy as the house itself. Humiliated and missing the comforts of status, former tsarina Alexandra often lashed out in anger. The oldest daughter, Olga, seemed distant, lost in her own thoughts.

But not everything was quite so dreary. On the contrary, the guards actually found themselves growing close to the people they were meant to despise. Many of them felt sympathy for the ex-tsar's son, Alexei, and Nicholas himself was personable and pleasant, at one point excited to recognize a guard from the days before the revolution (via Greg King's "The Fate of the Romanovs"). The daughters made an even stronger impression, genuinely making friends with the guards; Marie was especially well-loved, and Anastasia's penchant for mischief was recalled fondly. Guards went out of their way to raise their spirits, and some even hoped that they might be allowed to escape. One man, Ivan Kleshchev, openly talked about rescuing one of the daughters to marry her, and rumors persisted of guards planning a large-scale escape for the family.

There's nothing twisted in sympathy — rather, the stories told by the guards are deeply human — but the futility of that sympathy is what's deeply tragic. Companionship couldn't do anything to change the Romanovs' fate, and many of the guards that befriended the family (Kleshchev, included) were there when they were brutally executed.

The execution of the Romanov family

On the morning of July 17, 1918, the White Army was approaching Yekaterinburg, and the Ipatiev House's nickname of "the House of Special Purpose" was about to take on new meaning. The family was led into the basement of the house where they were met by a firing squad and were executed at gunpoint.

But the true horror is in the details, with the execution actually being a 20-minute, panicked bloodbath. Executioners intentionally fired on the wrong targets, and some of their bullets ricocheted off the walls, unintentionally hitting other guards. But even the bullets that did hit their correct targets weren't always lethal; the Romanovs had sewn jewelry and diamonds into their clothes, and doing so had, effectively, made the children bulletproof. Chaos ensued and screams filled the air as the surviving family members tried to flee. Guards unloaded as many bullets as they could into their victims, but even then, when the dust settled, not all of the family had died, still groaning in pain. Ultimately, the executioners relied on ruthless stabbing with knives and bayonets, or shots to the head. Then, when it came time to hide the bodies, the leader was committed to rendering them unrecognizable, smashing in the skulls with rifle butts and burning them with sulfuric acid and gasoline.

On top of all of that, the residents of Yekaterinburg most likely heard everything — all of the shots and screams — at least, if the lights of nearby houses flickering on in the midst of the violence means anything.

The Cheka and the Red Terror

When it comes to overwhelming acts of violence committed during the Russian Revolution, there are a couple of things you're liable to hear about immediately. Speaking most generally, there's the fact that the Bolsheviks officially sponsored widespread violence — a policy known as the Red Terror and started in 1918, which was essentially meant to ensure their hold on power. Political enemies and dissidents were the intended targets, but inspiring fear in the rest of the population was also a definite goal. By the official end of the Red Terror in 1922, at least a million people had been killed (though the true number could easily be higher), with some 10,000 of those deaths occurring in just the first couple of months.

And when it comes to the Red Terror, there's one other question: Just who was in charge of those deaths? And that's where the Cheka comes in. Founded in 1917, the Cheka was the Bolsheviks' secret police force, initially meant to investigate "counter-revolutionary" actions. This is scary in and of itself, but the group only grew in power, often acting as the vicious hand of supposed justice behind many of the darkest moments of the Red Terror. (Then, there's a legacy to consider as well. The Cheka was the first incarnation of the secret police, which would eventually become the infamous NKVD, the enforcers for Joseph Stalin's Great Terror years later.)

Blood-soaked responses to worker strikes

With the inception of the Red Terror and the creation of the Cheka, the Bolsheviks made it clear that they were more than willing to use brutal force against those that they considered political enemies. But that didn't mean civilians were safe. In fact, Vladimir Lenin made it explicitly clear that being a member of the working class meant very little, at the end of the day, even if the revolution was technically for the benefit of the working and the poor. In his own words, "Revolutionary violence cannot be withheld from use also against wavering and irresolute elements among the working masses themselves" (via George Legett's "The Cheka").

And that was no idle threat. On multiple occasions, workers in different parts of Russia would strike, often protesting the generally low standard of living they were suffering through, or due to the arrests of anyone who opposed the Bolshevik party in any way. The Cheka was dispatched to deal with strikers, and they typically did so violently, carrying out executions with victims that could number from a few dozen to a few thousand. Not only that, but these weren't always simple executions carried out with firearms; in one case, victims were weighed down with stones before being dumped into a river, a slow death by drowning.

The first Russian concentration camps

When it comes to brutal concentration camps in Russia, the first things to come to mind might be Joseph Stalin and the gulags. But Russian concentration camps actually got their start during the Russian Revolution, run by the Cheka.

For an example of those early camps, you'd just have to look to Kholmogory. The region had already gone through quite a bit of turmoil — an anti-Bolshevik uprising was met with terror propagated by both sides before being soundly crushed — and in retribution, cities like Kholmogory became the first homes to forced labor camps. Really, though, they were death camps. Anyone seen as a threat against the Bolshevik regime was sentenced there, whether they were former government officers or ordinary civilians in the wrong place at the wrong time, then seemingly killed whenever the Cheka officers saw fit. Stories say that some dozen people were killed each day, whether by drowning, shooting, or a number of other terrible methods. While the camp ran from 1920 to 1921, over 8,000 people disappeared, but the exact statistics on total deaths have been lost to time.

That said, the legacy of those camps hasn't disappeared. The old site of the Kholmogory camp was a reliable place for medical students in the 1930s to just dig and find bodies for study. Even in the years following, locals cleaning up or digging in the fields could stumble across human remains. Then, of course, there's the evolution of those Cheka camps into the infamous Soviet gulags.

The Allied Intervention

When it comes to the Russian Revolution, the simultaneous waging of World War I is important to remember. Once Vladimir Lenin and the Bolsheviks came to power, they drew Russia out of the war — something the rest of the Allies weren't pleased with. After all, one less combatant only made the situation better for Germany.

What followed was a military and diplomatic mess called the Allied Intervention. The governments of Britain, France, and the U.S. sent thousands of troops to Russia with the vague purpose of getting the White Army into power. But the details are where everything starts breaking down. Government officials in both Britain and the U.S. couldn't agree on why they should get involved, or if they should at all. President Woodrow Wilson's own writing on the topic skirts around the question; some troops actively fought in the civil war against the Bolsheviks, while some actually fought against their supposed White allies. British troops were often just as confused, with one soldier even explaining, "[I] never really met any Russians at all or had any idea why I was there" (via History Extra).

Needless to say, the decision to meddle in Russian affairs was wildly unpopular. As World War 1 came to a close and 1919 rolled in, Allied troops were still fighting and dying in Russia, desperate to get home. Opposition continued to grow on all fronts, but the failed experiment wasn't even fully abandoned until early 1920.

Allied forces also made concentration camps

Oftentimes, conversations about concentration camps in the 20th century tend to circle around the Holocaust and the Nazis. Or maybe the Soviet gulags. Typically, they aren't tied to the Allied forces, but that assumption is far from correct.

The Allied Intervention was meant to aid the White Army, and that aid included running prison camps, including one on Mudyug Island colloquially known as "Death Island." The camp itself (run by Britain and France) was confused from the outset; arrests happened before the camp existed, meaning that early prisoners had to build their own prison. Aside from that, foreign soldiers didn't know the nuances of the conflict and were liable to arrest anyone who seemed suspicious, Bolshevik or not. But the macabre nickname came from the conditions inside the camp. Part of that was the active violence: executions of those who tried to flee, or "ice cells" left open to the harsh Russian winter, leaving prisoners with frostbite if it didn't kill them. But there was also neglect; prisoners had to scramble for scraps of food, and diseases like typhus and scurvy spread like wildfire. Hundreds died, and the officers in charge justified the suffering, saying that it was really nothing compared to the violence of the revolution overall.

But the suffering caused on Mudyug Island might have even lasted beyond the camp's lifespan. One of the prisoners, Mikhail Kedrov, would go on to become the Cheka officer infamous for running northern Russian concentration camps — including the one in Kholmogory.

The Famine of 1921

The early 1920s proved to be something of a perfect storm when it comes to incredibly unfortunate circumstances, resulting in widespread suffering during the Famine of 1921.

Now, the causes behind the famine vary, one of which was decreased agricultural yield; between World War I, the Russian Revolution, and the effects of both of those events on the tools that farmers had at their disposal, grain yield had decreased by about 50%. Add into that some massive droughts, and production itself would naturally be down. But the famine wasn't born out of entirely natural causes; on the contrary, in certain areas like Ukraine, at least, the problem was made infinitely worse as a result of Bolshevik policies. Ukrainian towns actually would've had enough to survive, despite bad harvests, but government officials were pressured into sending food to Russia, instead. The Ukrainian people were effectively left to starve.

The result of all of this — both the falling production and government mismanagement — was horrific, to say the least. With over 30 million people affected, mortality was so high that corpses quite literally piled up in front of cemeteries, too numerous to be properly buried. Not only that, but starvation wasn't the only killer, sometimes just being the harbinger of diseases like typhus or cholera. But perhaps worst of all? People were so hungry that they resorted to eating anything; sometimes, that meant eating dirt, but other times, it actually meant cannibalism.

The crushing of the Tambov Rebellion

The problem of food supply in early 20th-century Russia was one that proved persistent, no matter who ran the government, though Bolshevik policies also made use of enforcers that were often indistinguishable from local bandits and drunkards (via Slavic Review). Needless to say, people weren't exactly happy with the way things were going.

Unmoved by the ideals and promises of the Bolshevik party and faced with nothing to lose, people began to fight back. Revolt officially broke out in 1920 as peasants marched on the city of Tambov, united in their anger and backing growing guerilla groups. That drew the eye of Moscow officials, who sent forces of their own, but as the conflict dragged on, both the rebels and Red Army began terrorizing villages.

As their leadership dissolved, guerilla groups were diminished to little more than roving groups of raiders, but Bolsheviks forces took things even further. The lines between active rebels and innocent civilians began to blur, and attempts to crush rebellions became accordingly (and intentionally) brutal. Wide swaths of village populations were arrested to make a statement and incite fear. Families of known rebels were treated like bargaining chips, thrown into concentration camps as a way to bait out those rebels, even though the families were, themselves, innocent. And, of course, there were also deaths. Mass executions were threatened on multiple occasions, and poison gas was even dumped into forests that hid rebel camps — a tactic that, it should be noted, had never before been used on civilian populations.

Germany likely wanted the Russian Revolution to be messy

It's really clear that the Russian Revolution turned out to be the stage for a lot of twisted stuff, and there's even evidence to say that Vladimir Lenin himself intended that. But Lenin likely wasn't the only one to expect chaos. After all, if you think about history, the Russian Revolution pretty directly led to the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, in which Russia pulled out of World War I. That was quite the tactical advantage for Germany, and it was no coincidence.

For all that Lenin's return to Russia was romanticized, it wasn't easy. In fact, his return had to be secret, because, well, the arrival of an exiled revolutionary who advocated militarism could spell trouble for anyone in charge. It was the German government that facilitated all of it, giving Lenin and his circle passage to Russia in a secure train car, predicting (correctly) that the chaos would lead to Russia's withdrawal from the war. Historian Edward Crankshaw (via Smithsonian Magazine) further explained that Germany likely saw Lenin as merely a fanatic, but one with enough influence to sow chaos in a country that was already teetering on the edge of disaster. If nothing else, Crankshaw's description of Germany's hope that Lenin would "spread infection" certainly doesn't paint a positive picture of the situation.

Interestingly, the Bolsheviks were apparently funded by the Germans more generally, too, which does fit with the situation overall (though it did lead to accusations by Russians of Lenin being a German spy).

Anti-Semitism and Judeo-Bolshevism

When you look through history, antisemitism is a terrible, continuous trend. It was already present in Russia prior to the revolution (pogroms — violent massacres of Jewish communities — began under the Romanovs), but in the years to follow, the myth of Judeo-Bolshevism began to spread, especially among the White Army.

Judeo-Bolshevism was, in a nutshell, the belief that Jewish communities were behind the Bolshevik Revolution, and that said revolution was the first step to effective world domination. The belief itself is heavily rooted in a lot of harmful stereotypes and little actual fact, but regardless, the White Army began to use it as justification for the widespread murders of Jewish communities. As they claimed, doing so was simply in pursuit of peace and stability, of putting an end to the Bolshevik threat on Russia. Unfortunately, that viewpoint did catch on, and the atrocities committed by the White Army are staggering, to say the least. In Ukraine alone, entire towns were massacred and looted en masse, with victims numbering from a few hundred to a few thousand in each separate instance. On the whole, between 1918 and 1922, Jewish victims in Ukraine and Belarus numbered around 150,000.

Perhaps even darker, though, was the longer-term effect that such a belief had, namely when it came to World War II. Adolf Hitler (and Nazi Germany in general) found Judeo-Bolshevism to be an effective weapon, just another way to vilify Jewish communities and attempt to legitimize their bloody methods in the process.