What Viking Funerals Were Really Like

Dramatic as our cultural image of Viking funerals might be, nailing down the details is seriously tough. First, there's the fact that few Norse people (the cultural and ethnic group that produced Viking raiders in the 8th through 11th centuries) wrote things down. They did have a written runic language, but it was most often employed in short form on monuments like picture stones or metal and wood objects. Full-text descriptions of Norse life don't come about until well into the medieval period, when many communities had Christianized, making these medieval accounts both possibly biased and far removed from the action.

What archaeologists can say about Viking funerals is that there was a lot of variation. How a Norse community chose to bury the dead depended on where they were, who they were, and who had died. And there's no evidence that anyone ever pushed a boat out to sea, then set it on fire with a flaming arrow. That myth appears to be a literary invention of Snorri Sturluson, the 13th-century Icelandic writer whose "Prose Edda" claims to relate the beliefs of Norse pagans. But we don't need flaming boats. The true world of Viking funerals is fascinating enough on its own.

Preparing the dead properly was important

One of the first things that happened after a Norse person died was preparing the body. In the "Prose Edda," Sturluson says that his pagan ancestors believed that any untrimmed nails left on a dead person would constitute building materials for the ship Naglfar. This vessel comes into play during Ragnarök, the apocalyptic battle of the Norse gods, where it will ferry monsters to face off against the gods who represent order. So, to keep Odin and company happy, the dead should have neatly trimmed nails, at least according to Sturluson.

The dead would also ideally be cleaned and then outfitted in new clothing that had been custom-made for the ceremony. Tenth-century writer and traveler Ahmad Ibn Fadlan traveled from his Arab homelands on a diplomatic mission, encountering Norse people known as the Rus along the way. His travelogue includes an account of a high-status Viking man's funeral in what's now part of Russia. Among the other details of his elaborate, days-long funeral, Ibn Fadlan notes that the living began to cut and sew new clothes for the dead man, as well as bedclothes made of pricey silk from Byzantium. The textile preparation was overseen by an older woman ominously known as the "Angel of Death," whom Ibn Fadlan claimed would continue to play an important role later in the festivities.

Cremation was connected to pagan belief

Broadly speaking, Norse bodies would face one of two fates: burial or cremation. For much of the history of the Norse people, cremation was linked to earlier pagan beliefs. According to Sturluson in the "Prose Edda," this was said to be on direct orders from Odin, who was, in turn, taking cues from the custom of his quasi-divine people, the Norse gods known as the Aesir (via "Children of Ash and Elm: A History of the Vikings" by Neil Price). Though it's worth remembering that Sturluson was writing at a fair remove from the pagan era and could have been biased in favor of Christianity, it does seem as if cremation was fairly important to earlier Norse people.

Cremations also rose and fell in popularity depending on where, exactly, you were in the Viking world. It was especially prevalent in what's now Sweden, while other Norse settlements in northern Europe tended more towards a mix of burial and cremation. Ibn Fadlan recounted that, when speaking with the Rus, he was informed that the Arab practice of burying the dead was a terrible idea. A Norse man told him that they believed burning the dead put them on the fast track to paradise. Leaving them to decompose in the ground was, for this group of Vikings anyway, unimaginably cruel.

Viking cremations were complicated and gruesome

Cremations during the Viking era weren't an easy affair. Where modern funeral workers can start an intensely hot and semi-automatic crematorium with the push of a few buttons, the Norse had to put in far more effort. Besides collecting enough wood for the pyre, they had to arrange the fuel just so to keep the flow of air going to the flames instead of burning down to a useless smolder. The whole affair would have required a careful eye and regular tending, whether that meant bringing more fuel around or moving the remains to make sure everything burned properly.

Old-school cremation was an ugly process. There's some archaeological evidence that the living might have removed a dead person's organs to hasten the whole thing, as indicated by cut marks on cremated bones. Even then, accounts from the era state that mid-cremation corpses were troublesome and gory things. Burning flesh caused eerie movements, while skulls were known to crack open. Some funeral attendees might even have been obliged to grab implements to push a body back into the flames after the intense heat caused sinews to contract, making it appear to sit up. Later, the ashes and bone fragments had to be collected for scattering or burial in a small grave.

Norse burials could be in simple graves or grand burial mounds

Some Norse burials were fairly simple, with a body placed directly inside a grave, perhaps inside a container or with grave goods. These could include blankets and pillows that may have reinforced the notion of the dead caught up in a kind of eternal sleep.

But Viking burials could also get pretty complicated, especially as the status of the deceased rose. Notable Norse dead might be buried in chamber graves, effectively small rooms dug into the earth and filled with goods for the afterlife. Those goods were often pretty high-quality, too, as chamber burials were typically reserved for high-ranking individuals who had access to pricey imported things. They have also been found seated, draped in jewelry, and cradling other objects in their laps, sometimes with sacrificed animals. Some inhabitants occupy their chamber graves alone, while others have companions, including couples and what appear to be groups of warriors.

Some of the dead were placed inside burial mounds, which could range in size from a barely detectable hill to massive earthworks that dominated the landscape. A few would have been reinforced with stones or enhanced with curbs, lintels, or other markers that were shaped or even carved all over with elaborate images. Toward the end of the Viking age, these could include runic inscriptions that give us a tantalizing glimpse into Viking writing.

A grave could be cracked open for a new funeral

Though there are quite a few Norse tales of treasure-hungry people who break into tombs and run afoul of the spirits of the dead, the reality is that tombs weren't always left alone after the funeral. There was grave robbing, sure — that's an awful lot of gold left in the ground — but there were also more legitimate reasons for someone to come along and reopen a grave. Archaeologist Raymond Sauvage, with the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) University Museum, told Norwegian SciTech News that his team's 2019 find of two nested boat graves was unique, in part because it was recycled. Sauvage speculates that his team's find, where a 9th-century woman was buried in a boat fitted inside the older burial of an 8th-century man, may have been done to reinforce ties to a high-status family — and to that clan's real estate.

Interring the more recent dead in an already established gravesite could call also upon the spiritual power and legitimacy of the previous tenant, even if the burial belonged to ancient pre-Viking inhabitants who would have never heard of Vikings. For the Norse — perhaps especially those in lands they were attempting to conquer, like in Britain — adding in a Viking grave or two could stake their claim as part of the local culture and history.

Most Vikings were buried with goods

Norse burials that took place after Christianity took over have practically no grave goods, but earlier Vikings were more committed to taking something with them. However, that's where the similarity ends. There was plenty of variation in grave goods according to region, class, and individual. Some goods left with the dead included swords, domestic tools, and valuable jewelry, while other, more mysterious objects like worn coins and stones may have held personal significance. Yet the poorest Norse folk were buried with practically nothing beyond their clothes and bits of jewelry.

Even those who were set to be cremated were placed on their funeral pyre with objects. Since many of the goods would have been burned beyond recognition, it's difficult to say exactly what those things would have been, but archaeological evidence suggests that cremated goods were similar to ones left in graves.

Tucking goods away in a grave or blasting to smithereens in an intensely hot cremation may have had a practical purpose, too. Writing in Revue D'économie Politique, Colin Harris and Adam Kaiser suggest that Viking burials in Iceland may have been so rich because families wanted to keep valuables out of circulation. Expensive bling could cause inheritance squabbles that led to bloody, long-lasting feuds. But, if left out of sight in the care of the dead, they could have been far less dangerous for those still living.

Some people were subject to traumatic burials

Though many Norse burials saw the dead laid in their graves as if they were sleeping, not everyone had such a peaceful time. Archaeologists have occasionally come across some inhumations that are downright strange in contrast, though they might not be as uncommon as the old term of "deviant burials" may imply. The remains inside these particular graves have been dramatically altered, including heads that have been lopped off, limbs twisted and broken, and heavy stones that were flung on top of the corpse. Others have been found buried face-down in prone burials that some speculate were meant to dishonor the dead.

Exactly why this sort of ritual trauma was inflicted on a dead body remains mysterious, though that hasn't stopped people from putting forth all sorts of theories. Some have suggested that this sort of postmortem abuse might have been a way to ostracize someone outside of society, including those who had committed a terrible crime. Others note that these burials might be for the spookier members of Norse societies, such as witches or shamans, whose bodies might have been thought to carry dangerous magical energy even after their death. This different treatment may have been an attempt to keep them contained within the grave. But, given how some prone burials were found next to more standard burials in Viking graveyards, it could be that another explanation for this unusual treatment of the dead is still out there.

High status funerals could include human sacrifice

Identifying which Viking graves contain sacrificed people can get tricky, but archaeologists have come across richly-appointed burials that include people who were clearly subject to traumatic injuries and postmortem modification. These include evidence of hanging, decapitation, and stabbing, any of which could have occurred at the time of the funeral.

But who were these sacrificed people? It's not as if Vikings left behind name tags, but evidence suggests that at least some were slaves. In a set of 10 burials first uncovered in 1980s Norway, four had been decapitated and ate a different diet than the rest. This indicates that they might have been sacrificed slaves, as University of Oslo archaeologist Elise Naumann told Live Science.

Also known as thralls, these or other enslaved people might have been Norse or could have been seized by a Viking expedition to a foreign land. Either way, they were an important economic component of the Norse world — even in death, where they might be pressured or forced to follow higher-status people to the next world. Funerals of big-name people might have required multiple human sacrifices.

The most complete account that outlines human sacrifice at a Viking funeral comes from Ibn Fadlan. His attendance at a Rus ceremony allowed him to observe the special treatment reserved for one young thrall who volunteered to accompany her master onto the burial ship, where she was ritually murdered.

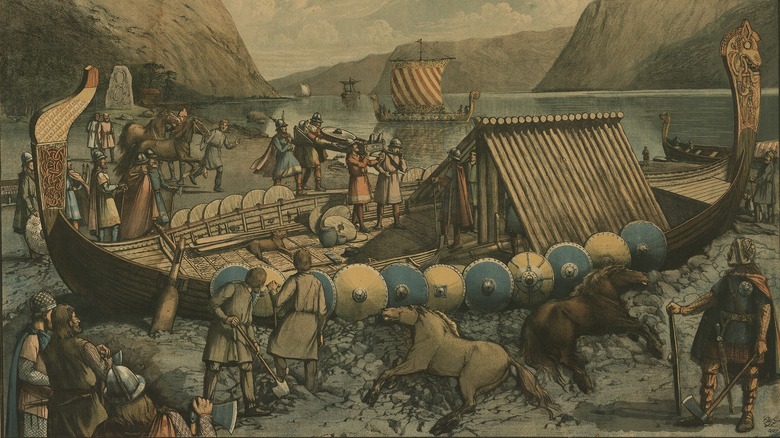

[Featured image by Carl Schmidt via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 4.0]

A few were buried in ships

For a small subsection of Norse society, they might be buried in boats. Some of these graves used relatively simple vessels, while others were monumental affairs packed full of grave goods. Other graves might not have any boats in them at all, but the people inside were deposited amongst stones that had been arranged to mimic a ship's hull.

The most spectacular boat burial uncovered so far is surely the Oseberg ship (pictured). First uncovered in 1903 in Norway, it was put in the ground around A.D. 834 and once contained the remains of two women. One was about 70 years old at the time of her death, while the other was about 50, based on an analysis of her tooth roots, according to a 2017 paper published in the European Journal of Archaeology. However, the fragmentary bones make a definitive age almost impossible to declare.

However old they were, both women were obviously a big deal in their community, judging by the numerous animals and expensive goods buried alongside them in the grand ship. These included four sleighs (three of which were intricately carved), costly imported textiles, and 15 horses. A chemical analysis of the bones indicated that both women also enjoyed a high-protein diet that would have been available to upper-class people. The ship itself was 71 feet long and may have been actively used before it was pulled out of the water and placed in the ground.

Viking funerals may have included mystic rituals

For the Norse, a funeral could be an occasion to peek into another world. Viking funerals could be rich with ritual, to the point where elaborate ones may have felt more like a religious or theater festival instead of a memorial. Because pre-medieval Norse people didn't really behind full written records of their lives and culture, we have to turn to the objects they left behind. Some excavated burial sites appear to have spaces that may have acted as stages for rituals, or causeways that would have seen grand processions. Meanwhile, objects deposited nearby might have also been left in the ground as part of the proceedings but not in the burial itself, like amulets, weapons, and tools.

In Ibn Fadlan's account of a Rus funeral, he notes that a young enslaved woman volunteered to be sacrificed alongside her dead master. Before meeting her end, she took part in an evening ritual in which she is repeatedly lifted into the air and asked what she sees. The first two times, she sees her family. The third, she sees her master beckoning to her from a blissful afterlife. She then sacrifices a chicken, gives away her jewelry, and drinks an intoxicating beverage after which, Ibn Fadlan writes, "I saw that the girl did not know what she was doing." Next, he remarks that she is taken into the ship, placed beside the dead man, assaulted by his retainers, and killed.

Viking funerals might include a feast

For both modern observers and contemporary attendees at Viking funerals, some of the rituals that went into the memorial were likely pretty intense. Funerals for high-status notables could mean a lot of animal and human sacrifices, not to mention the disheartening sight of all that expensive stuff going into the ground or burning up in a fire. But it wasn't all about the grim beating of spears on shields to drown out the shrieks of sacrificial victims. Often, there was even a party with plenty of food and booze.

However, accounts of Viking funerals indicate that these weren't collegiate-style free-for-alls. The feasting and drinking were also accompanied by ritual songs and chants, all meant to honor the dead and properly mark their passing into the next world. Sometimes, the feasting may have been an excuse to get everyone together to wrap up some final bureaucratic details. One particular feast, the Sjaund, was held seven days after the death and included practical matters like distributing the deceased's property and goods.

Screwing it up could mean a haunting

Perhaps for the funerals of lower-class people, it was sufficient to give them a simple but meaningful sendoff. But, for high-ranking Norse, the necessary rituals could get complicated. Ibn Fadlan writes that, after human sacrifice, a chief's ship was set aflame. The honor of starting the fire went to the dead man's closest male relation, who approached the boat not just backwards, but nude and covering his bottom.

If you messed it up, you wouldn't have just grappled with a guilty conscience. The whole community might be left dealing with an angry and dangerous spirit. The worst was surely the draugr, who pulled itself out of the grave to wreak havoc. These weren't ethereal wisps, either, but massive quasi-human creatures that wielded terrible and deadly strength.

To avoid this, Norse people might be careful to only move the dead through doorways foot-first, wrapping up the deceased's head (so they couldn't see), and sewing or tying the feet together. Those who were especially nervous might opt for a corpse door, in which a door was cut out of the home for the sole purpose of getting the dead body out. It would then be sealed, so that a wandering spirit — believed to only enter through the door it left by — couldn't get back in. For many Norse people, doors in general were powerful metaphors for the transition between the world of the living and that of the dead.