What The 1972 Miami Dolphins Look Like Now

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

There are great football teams and even greater football teams, and then there are the 1972 Miami Dolphins. You may not think of the Fins as sterling examples of football excellence; heck, even Dan Marino, the best quarterback they ever had and one of the greatest of all time, couldn't propel them to a win in the big game even once during his career. But before Marino, way back in the '70s when everything looked scratchy and lo-res, Miami appeared in three Super Bowls and won two — and the '72 squad set a standard that no team has been able to match since.

Quite simply, the Dolphins won every single game they played that year, despite losing their starting QB to injury early in the season. Sure, this was back when a season consisted of 14 games and not 16, but this matters little; if going undefeated and winning the Super Bowl weren't virtually impossible, it would have been done again at some point. Even the 2007 New England Patriots, who finished the regular season and playoffs undefeated, had their bid to outdo the '72 Fins squashed by the New York Giants in the big one. There's a (probably untrue) urban legend that every season, surviving members of Miami's legendary team pop a bottle of champagne when the last undefeated team loses — a ritual they could have enjoyed every season for over four decades. Here's what key members of the team are up to today.

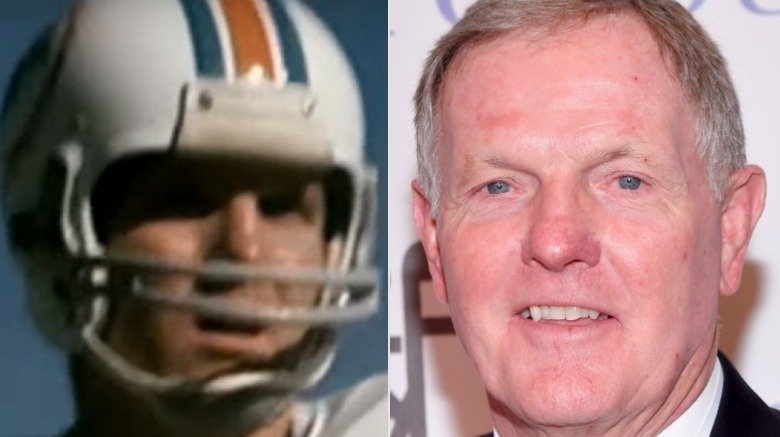

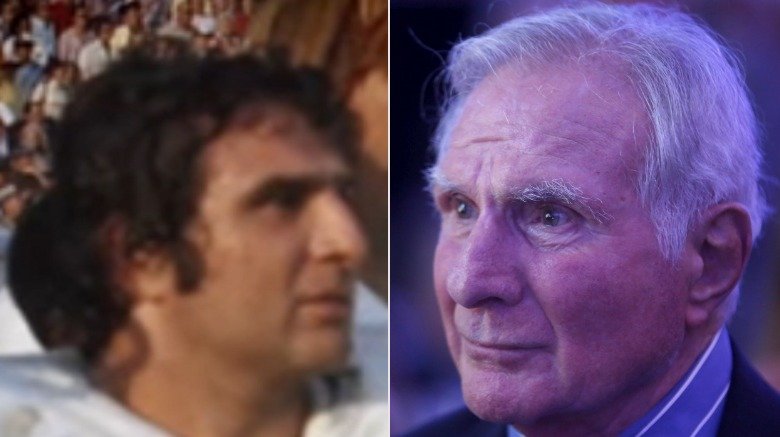

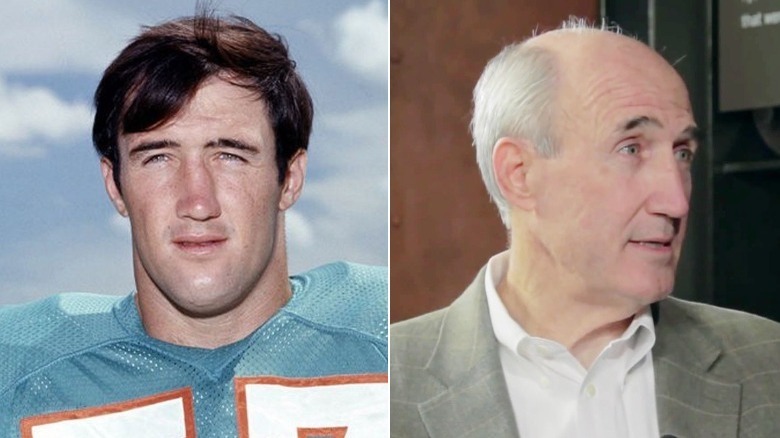

Bob Griese

Quarterback Bob Griese played 14 seasons for the Fins from 1967 to 1980, and in the days before the like of Troy Aikman and Peyton Manning, he was known as the "thinking man's quarterback," which actually kind of sounds like a sideways insult. He's one of only three players to have his jersey number retired by the Dolphins, and in '72, he looked to be on fire through the first four games — before suffering a broken ankle in Week 5, an injury that's pretty tough to play through. Backup Earl Morrall (who passed away in 2014) completed the regular season and most of the playoffs before giving way to Griese in the second half of the AFC Championship and the entirety of the Super Bowl.

After his retirement, Griese became one of the most celebrated and respected analysts in pro and college football, with high-profile gigs including a slew of Bowl games and Super Bowl XX. He also produced another NFL quarterback in son Brian (whose career was full of ups and downs in equal measure) and became a chairman of Moffitt Cancer Center's national Board of Advisors after losing his wife to cancer in 1988. He's also written a couple of books, entitled "Perfection" and "Undefeated." Take a wild guess what they're about.

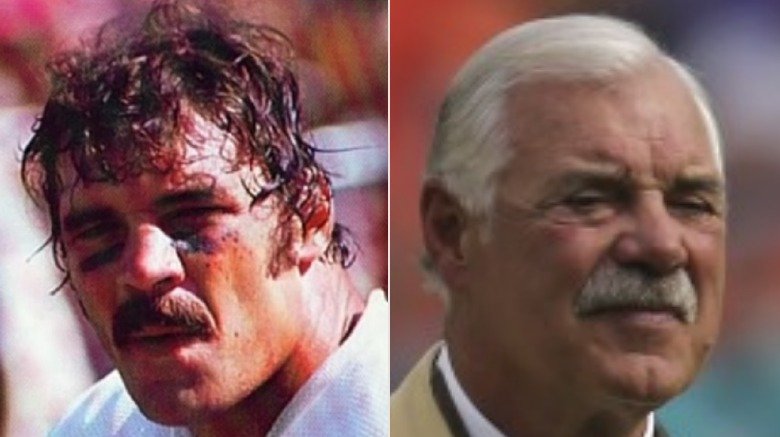

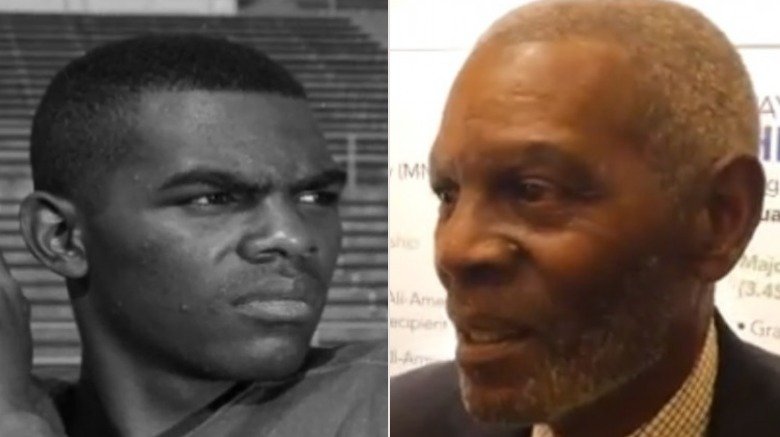

Larry Csonka

Larry Csonka was built like a defensive end, but he was an offensive player, not a lineman. He was a freaking fullback, and when he wasn't opening up king-sized lanes for speedy running backs Mercury Morris and Jim Kiick, he was carrying the ball himself — right through anyone unlucky enough to be in his way. Said former Minnesota Vikings linebacker Jeff Siemon, "It's not the collision that gets you. It's what happens after you tackle him. His legs are just so strong he keeps moving. He carries you. He's a movable weight." Csonka's toughness earned the respect of everybody on the field at all times, and he made the Pro Bowl for five consecutive seasons, with the 1972 campaign smack dab in the middle.

Csonka parlayed his fame into a notable television presence after retirement, appearing in commercials and in guest spots on outdoor shows, and readers of a certain vintage may remember him as the original host of American Gladiators in the early '90s. Today, the avid outdoorsman and his longtime partner Audrey Bradshaw live in Alaska, where — according to Csonka's official website — they hosted and produced the cable TV series "North to Alaska, Csonka Outdoors," and "Suzuki Great Outdoors." Now retired from television, Csonka presumably spends his days kicking the crap out of those great outdoors.

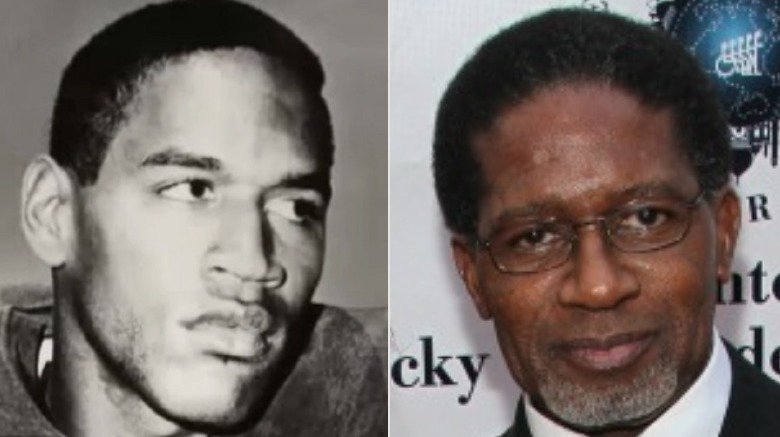

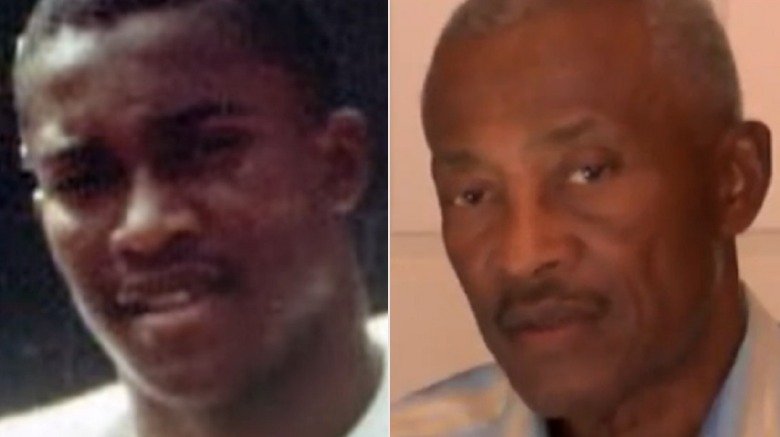

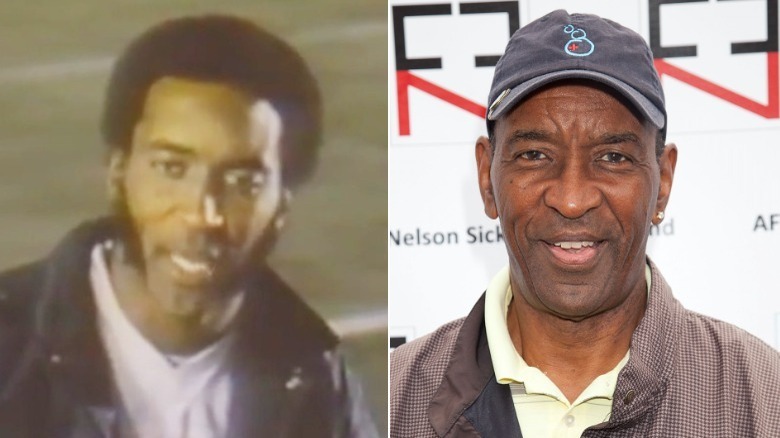

Mercury Morris

The '72 Dolphins' game was all about using the threat of the deep pass to set up the run, a novel strategy at the time and one that paid off in a big way. Key to this plan was running back Eugene "Mercury" Morris, who provided the Lightning to Csonka's Thunder. The duo became the first pair of NFL running backs ever to each amass 1,000 rushing yards in a season, as Miami's ground attack simply overwhelmed opponents. Reflecting on the Dolphins' perfect season, he once said, "It never occurred to us that going undefeated was a goal. We just went out there and wanted to win. The first time anyone on the team used the word 'perfect' was when it said we had won the Super Bowl and it said that on the scoreboard. Perfection is a myth. Winning isn't."

That's pretty badass, but Morris had some tribulations to overcome on his way to his present-day status as a strong advocate for the NFL to take better care of its veterans. He was convicted of cocaine trafficking in 1982, and was facing 20 years in the slammer until the Florida State Supreme Court overturned the conviction due to a slight case of bad prosecution. He wrote a book about the ordeal in 1988 and has done the rounds as a motivational speaker before becoming a crusader for veterans' rights.

Nick Buoniconti

Linebacker Nick Buoniconti may be the most well-known name on Miami's defensive unit from '72, but that's not saying much. There weren't any big, flashy, loudmouth players on the defensive side of the ball as is common today; it was a squad that kept their heads down, largely avoided the limelight, and quietly went about the business of smacking the snot out of opposing offenses. Such was the D's lack of starpower that it became known as the "No-Name Defense" — but if the fans didn't know their names, offensive players around the league certainly did.

Buoniconti stayed pretty busy after retirement, appearing in commercials (including an ingenious variation of the Miller Lite "Do you know me?" campaign taking full advantage of the whole No-Name thing) and on HBO's "Inside the NFL." Unfortunately, Buoniconti passed away from pneumonia in 2019, and in his final years, he made headlines for a really, really unfortunate reason: like many members of the '72 Dolphins squad, he experienced serious issues with cognitive decline. The troubles began in his mid-50s, compelling him to speak out in light of the recent wave of publicity surrounding the dreaded CTE, a loss of cognitive function caused by repeated blows to head which affects a significant number of NFL players. True to form, however, the bruising linebacker never stopped fighting until the very end.

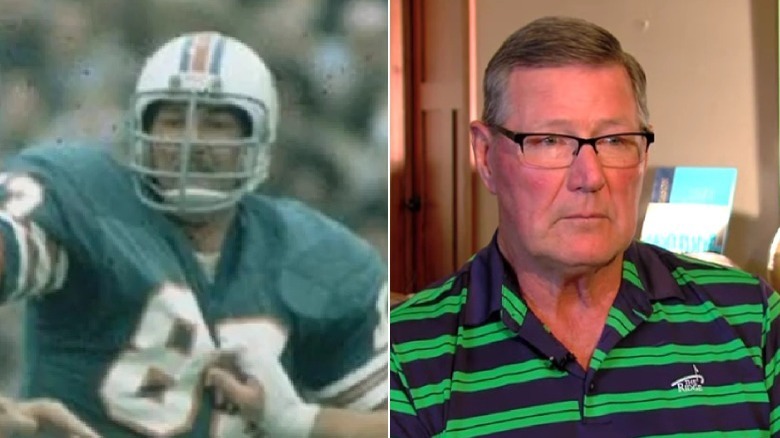

Paul Warfield

Arriving in Miami after a blockbuster trade with the Cleveland Browns in 1970, receiver Paul Warfield was key to coach Don Shula's vision. A lightning-quick receiver who could get down the field in a hurry, Warfield provided the deep threat necessary for Csonka and Morris to rack up all those yards. As graceful as he was quick, Warfield only totaled about 600 yards during the 1972 campaign — but this was by design. Despite playing on such ball-control offenses for most of his career, he managed to establish a career yards-per-catch mark of 20.1 — to this day, still among the best ever.

Warfield returned to Cleveland in 1976 and retired a Brown the following year. His post-retirement career consisted of a number of front office positions, including serving as a personnel consultant for the Browns and Dallas Cowboys, and he was director of player relations for the Browns for a couple years before their move to Baltimore, which secured owner Art Modell his special place in Football Hell. Warfield has been officially retired since 2010, and though he still hangs around the Browns' facility to offer up personnel opinions from time to time, he's been pretty much just taking 'er easy with his wife, Bev.

Larry Little

The career of offensive lineman Larry Little began when he was signed as an undrafted free agent by the San Diego Chargers in 1967 and wound up with two Super Bowl rings and a Hall of Fame induction. The bruising guard was the lead blocker on Miami's nearly unstoppable sweep plays. He was a five-time Pro Bowler, was selected as the AFC's Offensive Lineman of the Year three freaking times, and only missed four games due to injury during his 11 seasons with Miami — in other words, he was the consummate badass, and he's fond of letting aspiring NFL stars know that you don't have to go high in the draft, or even get picked at all, to be great.

"Every year, I talk to the Dolphins rookies who come in," Little said in one interview. "There are a lot of undrafted free agents in that room, too." He reminds them that of the 17 players the Chargers picked in the draft in '67, only two were still in the league five years later — while he, who signed to the team for a paltry $750 bonus, has a bust in Canton. "I tell those guys, 'Just because you're a free agent, that doesn't mean you won't be good enough to play in this league ... I made my way all the way to the Pro Football Hall of Fame."

Jim Langer

Larry Little's teammate Jim Langer took a somewhat similar route to Super Bowl glory, being signed as an undrafted free agent in 1970 by the Browns before being cut in training camp and bolting to Miami. He only saw limited playing time in his first two seasons, but in 1972 he was elevated to starter, which he took full advantage of by becoming one of the most efficient players on Miami's stellar offensive line. Langer played in 141 consecutive games for the Fins, went to six straight Pro Bowls, and played in three Super Bowls — not bad for an ex-linebacker who went to school at South Dakota State. (It's ... not a large school.)

These days, he likes to do not a whole heck of a lot. "I mow my own lawn. I don't do much. I'm pretty boring," he said during a 2016 appearance at Royalton High School in St. Cloud, Minnesota, where he was a standout multi-sport star in the '60s. His knees are kind of shot, and he doesn't do many public appearances anymore, but this one was special: It was in honor of Royalton High being named an official "NFL Hometown Hall of Fame" school, one of under 100 designated as such by the league.

Norm Evans

Offensive tackle Norm Evans has an interesting legacy outside of his ten seasons with Miami: he was picked in the 1976 expansion draft to become the first to ever play the position for the Seattle Seahawks, staying there for three seasons and helping establish the team which, at the time, stunk. Badly. "Truth was, we weren't very good," Evans said, generously, in an interview with the Seattle Post-Intelligencer. "But it was fun to play here."

The '70s Hawks didn't exactly live up to the standard of excellence Evans was used to, but during his Miami years, he was another crushing standout on the offensive line (you may see a theme developing here), who played in all three of the Fins' Super Bowl appearances and was selected to two Pro Bowls. Since the '80s, he's been helping to spread the word o' the Lord to NFL players through Pro Athletes Outreach, an organization he presided over for 26 years. But he's not all about the love; he admits to being pretty psyched when the Giants took out those '07 Patriots in the Super Bowl. "Absolutely, I'm as selfish as the next guy," he says. "I'm a closet Giants fan."

Marlin Briscoe

The Dolphins' receiving corps was pretty much there for the purpose of picking up key first downs and keeping the defense honest so Csonka, Morris, and Kiick could waltz through hapless defenders. But receiver Marlin Briscoe, not as flashy or quick as Paul Warfield, has himself a claim to fame that no man can ever take away: He was the first black quarterback to start in the AFL, calling signals for the Denver Broncos as a rookie in 1968, which you may recognize as a rather historically important year in race relations.

You see, in the '60s, things were much different from and even racist-er than today. AFL and NFL execs simply weren't convinced that a black guy could handle the QB position, until Briscoe kicked down the door for all the Williamses, Cunninghams, Moons, and Newtons who followed. After a rookie campaign with Denver, Briscoe was switched to the receiver position for all of his subsequent seasons, grabbing two rings with the Dolphins before finishing out his career at San Diego, Detroit, and New England. Despite playing for the fabled '72 Dolphins as a receiver, Briscoe always considered himself a quarterback first. Asked what he considered to be his greatest pro accomplishment, he said, "Playing quarterback for the Denver Broncos and proving that a black man could lead... I proved [everyone] wrong, all the way to the pros."

Prove it he did, and perhaps soon, his story will get just a bit more exposure. According to IMDb, a feature film based on his life, from "Remember the Titans" scribe Gregory Allen Howard, is currently in development, sporting as its title Briscoe's nickname during his playing days: "The Magician."

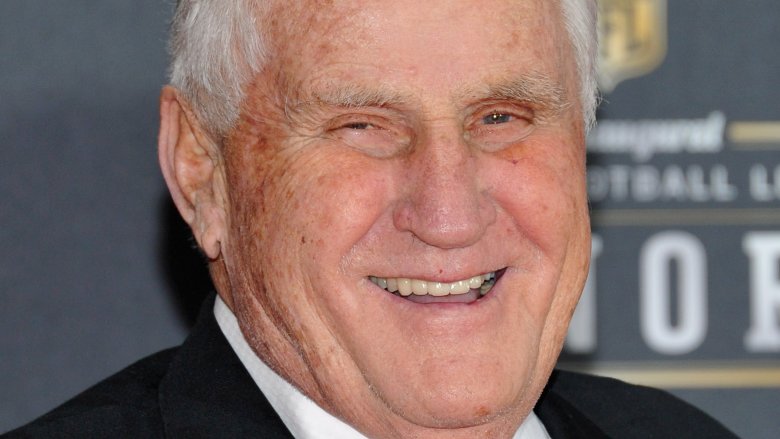

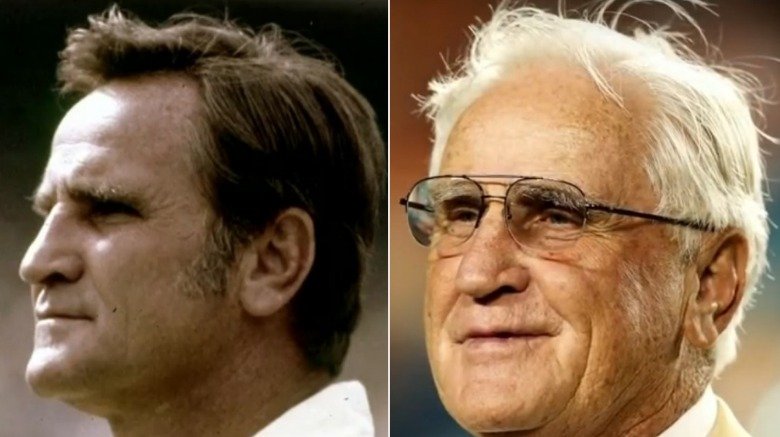

Don Shula

When children to go bed at night, they look under their beds for the boogeyman; when New England Patriots head coach Bill Belichick goes to bed at night, he checks under his bed for Don Shula. Belichick is an insanely driven man, and his failure to match Miami's perfect season has got to stick in his craw — but on top of that, Shula owns the NFL's all-time win record, and it's not close. The Pats' mastermind would need a good three or four more stellar seasons to even hope to catch up.

Mr. Dolphin coached the team for 25 freaking years, took no fewer than three quarterbacks to the Super Bowl during his career, and racked up his eye-watering 347 wins largely during an era when there were fewer games per season. Unfortunately, Shula shuffled off this mortal coil in 2020, but his long retirement consisted largely of chillin' out and enjoying the weather in Florida, where a chain of successful steakhouses can be found bearing his name (via South Florida Business Journal). His legacy will doubtless inspire future generations of coaches, and it's a testament to the man's class that he declined to have "EAT IT, BELICHICK" engraved on his tombstone.

Mike Kolen

Standout Auburn linebacker Mike Kolen had a bit of an inauspicious entry into the NFL. According to AI.com, he was drafted by the Fins in the twelfth round of the 1970 NFL draft (yes, there were a lot more rounds back then), and he came into training camp a bit undersized for his position. By the preseason, though, he was bench-pressing twice his weight and wowing the coaches with his work ethic, and it wasn't long before he earned the nickname that would stick with him for the rest of his career: Captain Crunch.

Kolen helped anchor Miami's linebacking corps for eight seasons, but other than the two Super Bowl wins, he's probably best-remembered for being smack in the middle of the infamous "Sea of Hands" play, in which — during a 1974 playoff game vagainst Oakland — Kolen was one of several Miami defenders who failed to intercept, swat down, or even headbutt a lazy floater of a pass thrown by Raider QB Ken Stabler into the end zone. Instead, per Raiders.com, the ball found its way through ... well, a sea of hands to somehow end up in the arms of Oakland running back Clarence Davis, clinching the win for the Raiders and effectively ending the days of Dolphin dominance. After retirement, according to Birmingham Business Journal, Kolen returned to Alabama to start his own financial services firm, where Captain Crunch crunches numbers rather than the bones of opposing offensive players; he is also the co-author of a 2015 book entitled "The Greatest Team: A Playbook for Champions," because he is nothing if not humble.

Marv Fleming

Tight end Marv Fleming has to have been one of the most well-coached players of this or any other era, for the simple fact that he began his career winning three NFL championship and back-to-back Super Bowls (the first two, in fact) with the Packers under legendary coach Vince Lombardi, and then ended it winning two more with Don Shula and the Dolphins, according to the Spokesman-Review. Playing in an era during which tight ends were considered to be more like glorified linebackers than pass-catchers, Fleming didn't see a heck of a lot of balls come his way — but when they did, he made it count. NFL.com reports that over his 12 seasons, he notched only 157 receptions — but amassed 1,823 yards, a sterling 11.6 yards per catch, and he found the end zone 16 times.

This is even more impressive considering that Fleming is fortunate to have survived long enough to make it to the NFL at all. According to the Press Times, he was involved in a gnarly car accident during his college days that left him with a broken neck (interestingly enough, the driver of the vehicle, his college roommate, happened to be George Seifert, who would go on to become the winningest coach in San Francisco 49ers history). Apparently, when you're a stone-cold badass, a little thing like a near-fatal injury just won't keep you sidelined for long. Fleming retired in 1975, and these days, he appears to spend most of his time taking 'er easy, signing autographs for Packers and Dolphins fans alike, and posting selfies with them to his Instagram.

Vern Den Herder

Defensive end and sack machine Vern Den Herder played all 12 of his pro seasons with Miami, and it's pretty terrible luck that the year he retired — 1982 — was the first year the NFL formally started keeping track of sacks. Just because the league wasn't tallying them doesn't mean that nobody was, however, and Den Herder's unofficial total of 65 (as reported by Pro Football Reference) was more than respectable, especially considering that his cohorts on the D-Line weren't exactly a bunch of wussies. We suppose this is only to expected from a hulking (6'6", 245 pounds), quick, cerebral lineman whom, according to Football Foundation, was singled out by Don Shula as the single most dependable player he'd ever coached.

As reported by Siouxland News, after his retirement, Den Herder moved back to his hometown of Sioux Center, Iowa, to become a farmer — and there he has stayed, holding down his family farm with his wife Diane, ever since. He built up his farm from a one-tractor, one-combine operation into a successful, four-decade-long enterprise, which is rather to be expected from a man of his tenacity (and, well, size and strength). He looks back on his football days with the fondness one would expect from a champion and the folksy, simple wisdom you'd expect from an Iowa farmer: "Actually went to 4 Super Bowls during my career. We won two and we lost two," he says. "We enjoyed winning them better."