Ten Epic Last Stands Throughout History

In sports, everyone loves a good underdog, especially the one who puts up a good fight before losing. If the underdog performs a feat of giant slaying, all the better. The same is generally true on the battlefield, where the stakes are not so much losing a game and exiting a tournament, but being killed and potentially losing an entire nation, culture, and way of life.

Last stands by underdogs are something that people everywhere are attracted to. Often, leaders and their troops who go down fighting in a blaze of glory, protecting their loved ones over surrender, become eternal heroes, examples of steadfastness that entire cultures and civilizations seek to emulate. Indeed, you don't need to read literature to appreciate their influence; they have inspired popular movies like "The 300" and Tom Cruise's "The Last Samurai."

But last stands have not always ended with the defenders going down in a blaze of glory. Sometimes, against all odds, the underdogs won. And several modern-day countries owe their very existence to a handful of brave warriors who preferred death to dishonor and surrender. Here are 10 of history's greatest last stands.

Thermopylae: The Gates of Fire

In 480 BC, Persian Shah Xerxes invaded Greece with an army so large that, according to the Greek historian and ethnographer Herodotus, its soldiers drank entire rivers and lakes dry. The panicked Greeks threw together a coalition to oppose this army under the command of Spartan King Leonidas, who marched north to oppose the Persians at Thermopylae – the Gates of Fire.

At Thermopylae, Herodotus recounts that the Spartans and their allies held off wave after wave of Persian assaults, to the point that even the Persian elite troops known as the "Immortals" could not make a dent in the allied lines. One day, however, a local Greek named Epialtes told the shah of a mountain path that came out behind the Greek line.

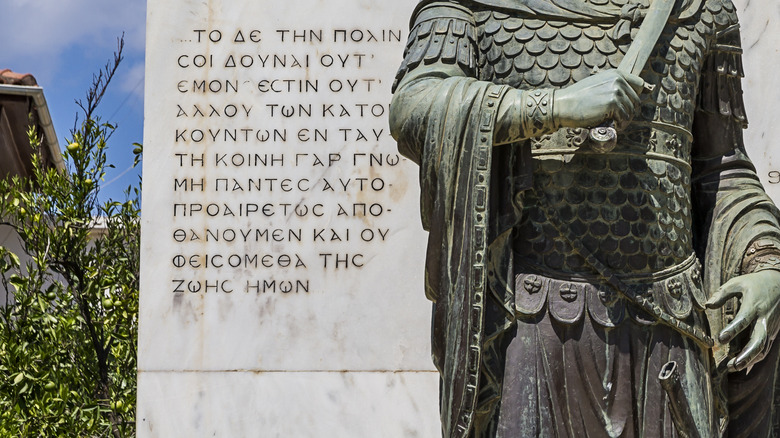

The Persians marched through the path overnight and overwhelmed the Phocians that Leonidas had left to guard it. In response, the Spartan king, knowing that it would likely be his last fight, sent his allies home. This left 300 Spartans and some Thespians, who refused to leave, to fight the Persians alone. In the resulting fight to the death, Leonidas was killed along with all of the men who had stood with him. Today, the battle is legendary as the epitome of fighting to defend one's country against foreign aggressors. Today, a giant statue of Leonidas adorns the battlefield, complete with the epitaph by Simonides of Ceos to the 300 dead, "Stranger, bear this message to the Spartans, that we lie here obedient to their laws."

Roman conquest of Northern Iberia

When the Roman Emperor Augustus took the throne, he set his eyes on completing a task that his predecessors had failed at in the previous two centuries: the complete conquest of the Iberian peninsula. The northern part of the peninsula had remained a hotbed of resistance to Roman rule, where Roman historian Orosius recorded that the "bravest peoples of Spain," the Astures and Cantabri, lived tucked behind their mountains.

In 28 BC, Augustus set out to conquer Northern Iberia with three armies and a large navy. First, he attacked the Cantabri, who put up a fierce fight. The tribe first engaged the Romans outside a town called Attica, but were defeated and holed up on Mount Vinnius. Preferring death to surrender, many starved. The town of Racilium fell next after brave resistance from the defenders. The remaining Cantabrians were holed up in their final stronghold on Mount Medullius. Here, they debated whether to surrender or die. Being men "by nature wild and fierce," they chose the latter, dying by suicide either through "fire, sword, or poison."

With the defeat of the Cantabrians, the conquest of the Astures was relatively easy. After losing to the Romans in the field following a betrayal, they took refuge in the town of Lancia. However, instead of fighting to the death however — perhaps having seen the fate meted out to their Cantabrian cousins — the Astures chose to surrender.

Fall of Constantinople

By A.D. 1453, the once-mighty Eastern Roman Empire had been reduced to a shadow of its former self, holding only the territory immediately around its capital, Constantinople. When Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II laid siege to the city that year, the outlook for the city was bleak. Nevertheless, Emperor Constantine XI prepared to defend the city, with assistance from the Italian cities of Venice and Genoa.

The battle for the city was fierce. With the help of the Italians, the 10,000 or so defenders held off the Ottomans from land and sea, despite a steady bombardment from Ottoman heavy artillery. But as it became clear that Ottoman numbers would win the day, Byzantine notables tried to convince Constantine to flee. He refused, and instead summoned his allies, soldiers, and subjects to attend liturgy for the last time in the Hagia Sophia Cathedral. He then rode off to meet his fate.

The details of Constantine's last stand are unclear and in part steeped in legend. But the general consensus is that he gathered a small group of Italian and Greek soldiers and threw himself into the fray. Supposedly inspired by the Bible, he is said to have told his men, "Whoever wishes to escape, let him save himself if he can; and whoever is ready to face death, let him follow me!" He and his men were cut down in the fighting, and his body was never recovered. Today, the last Byzantine emperor is considered a hero in Greece, where his statue adorns the capital of Athens.

Storming of the Tuileries Palace

In 1791, King Louis XVI of France attempted to escape the French Revolution to Austrian territory. He was captured and placed under house arrest in the Tuileries Palace, along with his queen Marie Antoinette, their children, and their loyal servants. There, a mob of Parisians and a detachment of National Guardsmen demanded entrance to the palace, according to American merchant James Price (via Journal of American Studies), who witnessed the bloody assault on the palace that followed.

According to Price, the mob wanted to loot the palace and prepared to bombard it with artillery. After executing a handful of royal guardsmen, the assault began in earnest. But the crowd had not counted on heroic resistance by Louis' elite Swiss guards. Initially, the National Guard attempted to convince the Swiss troops to surrender.

The commander of the guard refused in a legendary retort recorded in Hippolyte Taine's "Origins of Contemporary France": We are Swiss ... the Swiss do not part with their arms but with their lives. We think that we do not merit such an insult. If the regiment is no longer wanted, let it be legally discharged. But we will not leave our post, nor will we let our arms be taken from us." The Revolutionaries waited a few hours and attacked the palace. The guardsmen fought valiantly, but were massacred, and the revolutionaries then proceeded to massacre the king's servants. The fighting ended when Louis, hoping to avert further bloodshed, ordered the guardsmen who had escaped to lay down their arms. Today, the Lion Monument in Lucerne commemorates their brave stand.

Zadwórze: The Polish Thermopylae

In 1920, Soviet Russia launched a massive invasion of Poland with the intent of triggering a world communist revolution. They did not, however, expect the newly-minted Republic of Poland to fight back.

Although the main battle of the war took place around Warsaw, another significant – albeit on a smaller scale – battle took place outside the Galician city of Lwów (modern L'viv in Ukraine). Soviet cavalry commander Simeon Budionny, who, according to Polish military author Witold Lawrynowicz was supposed to support the attack against Warsaw, was persuaded by Joseph Stalin to attack Lwów instead. There, per the Institute of National Remembrance, his approximately 3,000 cavalry met a force of 330 Polish militiamen – mostly teenagers from Lwów – near the village of Zadworze.

Despite the odds, the Polish militia fought hard and well, holding off Budionny's cavalry until the Lwów garrison could organize a proper defense of the city. By the end of the battle, although only 12 were left, their stand paid off. Lwow remained Polish, while Budionny's cavalry force, tied down outside the city, was unable to support the main Soviet thrust against Warsaw. General Władysław Sikorski noted seven years later that Zadwórze was "a symbol of a sacrificial soldier who served the country faithfully to the sacrifice of life." Today, the battle is known as the Polish Thermopylae and the soldiers who died there the Lwów Eaglets, in honor of Poland's national symbol — the White Eagle of Gniezno.

Siege of Gaeta

Francesco II was the last king of the Two Sicilies, which controlled southern Italy and the island of Sicily. In 1860-61, the Kingdom of Piemonte (later Italy) invaded his kingdom, per the San Felese Historical Society. Francesco's 16,000 soldiers left Naples, pursued by twice as many Piemontese soldiers under Giuseppe Garibaldi and General Enrico Cialdini. After a defeat at Volturno, Neapolitans made a last stand at the fortress of Gaeta on November 13, 1860.

The privations of war took their toll on the defenders, who faced a never-ending bombardment, lack of supplies, and a typhus epidemic. Napoleon III of France's navy prevented the Piemontese from shelling the fort from the sea, but the French emperor, who wanted Francesco to surrender, was threatening to pull his ships from Gaeta. But the Neapolitan king refused to surrender.

Despite their advantages, the Piemontese faced the problem of integrating former Neapolitan soldiers, many of whom were loyal to Francesco II, into their ranks. As long as the king held out in Gaeta, there was a chance of mutiny. So as soon as Napoleon pulled the French fleet from Gaeta, Piemontese ships joined the army in shelling the fort. It paid off when a shell struck the munitions depot and triggered a massive explosion that destroyed a quarter of the fortress. Seeing the game was up, Queen Marie Sophie of the Two Sicilies, following a letter from Empress Eugenie of France, convinced her husband to surrender. The couple went into exile with the pope in Rome, leaving their kingdom to the new nation of Italy.

Covadonga

In 722, the once-thriving Visigothic kingdom of Iberia was no more, shattered by a Muslim Umayyad invasion that conquered most of the peninsula. The Spanish Cronica Albeldense (via Kenneth Baxter Wolf's translation in "Conquerors and Chroniclers of Early Medieval Spain"), however, recounts that a Visigothic noble named Don Pelayo refused to surrender to the occupiers.

The Umayyads sent an army north under a general named Al-Qama to crush Pelayo, whose band of Asturians was becoming a serious headache. Outnumbered but certainly not outmaneuvered, Pelayo withdrew deep into the mountains of Asturias to a place called Monte Auseva, where he could fight the superior forces on his own terms.

For the Umayyad forces, victory — at least on the surface — looked tantalizingly easy. Al-Qama, however, realizing that the mountains complicated matters, sent Don Oppas, the Archbishop of Seville, to negotiate Pelayo's surrender. In a legendary reply, Pelayo chastised the bishop for betraying the Catholic Church and the Visigothic people to foreign invaders and declared he would not only fight the Muslims – he would also win. In the ensuing battle, Pelayo's forces scored a spectacular victory, aided by the terrain (and divine intervention, according to legend). He became the first king of Asturias, which eventually evolved into the modern nation of Spain.

Great Siege of Malta

In 1565, the Ottoman Empire invaded the tiny archipelago of Malta with 40,000 men. Opposing them was a tiny force of the Crusader Order of the Knights of St. John, under Grandmaster Jean de la Valette, according to History Extra. The Knights' glory days were long gone, but with Christian Europe's future on the line, they were eager to have their day in the sun – even if it was their last.

To win, the Ottomans needed to take the knights' four strongholds. They wasted no time, capturing St. Elmo after a month-long siege. However, it was a pyrrhic victory: St. Elmo's 1,500 defenders inflicted nearly 8,000 casualties on the attackers. The Ottomans then turned to Senglea, whose inferior defenses should have made for an easier victory. The first attack was repulsed, but the Ottoman commander Mustafa Pasha had held his elite janissaries back. They promptly sent them in to finish the job. But the knights had hidden some artillery where they were supposed to attack, and as the janissaries landed, they were shot to pieces.

The siege was becoming a slog. Two more attacks against Senglea and Birgu fell short, and the knights were even able to attack the Ottoman camp, killing the sick and wounded and burning supplies. Mustafa then received the worst possible news: Spanish reinforcements had arrived from Sicily. With his exhausted plague-stricken army facing the possibility of a pitched battle against fresh enemies, Mustafa withdrew, resulting in a spectacular victory for the defending forces that broke the aura of invincibility that the Ottoman Empire had enjoyed since 1453.

Battle of Azua

In 1844, the Spanish-speaking half of the island of Hispaniola launched a war of national liberation against Haiti, styling itself as a new country called the Dominican Republic. The Haitians, however, were determined to crush the rebellion and keep the island of Hispaniola under their control. And they considerably outnumbered the ragtag forces the Dominicans had on hand.

The Haitians invaded the new republic with a force of 30,000 men under President Charles Herard. Split into three groups of 10,000 each, one of the columns advanced on Azua, where the Haitians encountered a force of less than 3,000 Dominicans, under General Pedro Santana and Antonio Duverge, blocking their way. It looked as if the Dominican Republic's first battle looked like it was going to be its last.

Given the Haitian numerical superiority, the battle should have been an open-and-shut case. However, superior Dominican tactics prevailed over Haitian numbers. Santana deployed his men along the major roads leading into Azua in small groups of around 200, and in the center of the Dominican defense were its two batteries of artillery. In the ensuing fight, the Dominican strategy of protecting the artillery paid off, as the Haitians had no response to volley after volley of cannon – despite their greater numbers. Although the defenders retreated to a more favorable position afterward, they had shown that the war was winnable despite the seemingly impossible odds. They were right, as the republic secured its independence from Haiti later that year.

Shiroyama: The last stand of the samurai

The Meiji Restoration of 1868 saw the Tokugawa Shogunate swept away in a bid to break the power of the samurai class and restore power to the emperor. The samurai, however, true to their code of Bushido, did not go down without a fight, staging the Satsuma Rebellion in 1877, per military historian Kennedy Hickman – an event that inspired the (highly fictionalized) film "The Last Samurai."

The rebels were at a disadvantage: They were outnumbered and faced an imperial Japanese army that had been modernized with the latest weaponry from Europe and the United States. But they could count on the leadership of former Japanese imperial Field Marshal Saigo Takamori, who joined the rebels against his old superiors at Kumamoto Castle. The imperial army threw him back, pursuing him until he only had 400 men remaining. Hemmed in on Shiroyama Hill near the city of Kagoshima, some of the rebels attempted to save themselves and their commander by negotiating a truce with the imperial forces. They refused, instead demanding Takamori surrender.

For Takamori, surrender was not an option, The samurai code of Bushido opted for death over dishonor, and he followed it to the bitter end. Japanese imperial forces shelled the remaining samurai and then attacked the exhausted rebels at 3:00 a.m. Reduced to a mere 40 men and mortally wounded, Takamori opted to die by seppuku – Japanese ritual suicide – instead of surrendering. Modern weaponry had bested the old nobility, and the samurai families, stripped of their power, positions, and influence, joined the new social order as ordinary citizens.