The Last Thing These US Presidents Said Before They Died

Approaching death can draw out the inner philosopher in anyone; when you've spent a portion of your life as leader of the free world, you're likely to have more to reflect on than most. Even before the United States achieved such a pivotal role in global affairs, many U.S. presidents who knew their time was coming had plenty to say about it. Some greeted death with humor; per The Los Angeles Times, Woodrow Wilson responded to news that Congress was praying for him by asking which way they wanted him to go when he died, while John Adams observed, "I have lived in this old and frail tenement a great many years. It is very much dilapidated, and from all I can learn, my landlord doesn't intend to repair it." Others were more reflective or melancholy; James Madison, having outlived many of the other Founding Fathers, wondered if he had outlived his own time and usefulness.

But those are the thoughts of men approaching death with some distance left to travel. What about presidential last words? There's a general interest in last words, and some credited to U.S. presidents have become famous even when apocryphal or confused (that John Adams and Thomas Jefferson both died on the 50th anniversary of the 4th of July is well-known, but Adams's "Thomas Jefferson survives" were his second-to-last words). Not all are so well-known, and not all were recorded, but here are the ways some of America's commanders-in-chief met death.

George Washington

After the Revolution, George Washington repeatedly expressed his wish to retire from public life, even as he oversaw the Constitutional Convention and was elected president twice. He was reluctant to accept either responsibility, and the farewell address he presented the nation with when he refused a third term has become one of the more famous pieces of his legacy. But Washington did not have a particularly restful time in private life, being deluged by visitors and driven by his own interest in the country's welfare to stay involved.

Nor did he have very long to enjoy his so-called retirement. Three years after the end of his second term, Washington fell ill after being caught out on horseback in the rain and snow. His condition, initially a sore throat, worsened over the next two days. Washington had a sense that whatever was wrong with him was fatal, and by the time a doctor arrived, he was fading fast. By December 14, 1799, he was dying.

Washington's final hours were well-recorded by his secretary, Tobias Lear, whose diary entry for that day are preserved at the National Archives. According to Lear, Washington was assuring his doctor by 5 PM that he was unafraid of death and that it was best to let it happen quickly. By 10, he asked that he wouldn't be buried until at least three days had passed. "Do you understand me?" he asked Tobias. When Tobias said he did, Washington said his last words: "Tis well."

John Quincy Adams

By 1848, John Quincy Adams was one of America's most accomplished statesmen. In his long career, he had served as ambassador, senator, secretary of state, president, and finally, congressman for Massachusetts in the House of Representatives. That last role kept him busy from 1831 to 1848. Though often in the minority and an adversary of the Jacksonian Democrats who held the White House, Adams was deeply revered by his colleagues. He was known as "Old Man Eloquent" and "Father of the House," and his oratories on everything from abolition to House floor rules were well-regarded.

It was during one such speech that Adams's long career began its end on February 21, 1848. According to PBS, he began the day in good health. He was one of the few opposed to a resolution honoring officers of the Mexican-American War, a conflict Adams had also been against. But when he stood to take questions, Adams suffered a massive stroke. His fellow congressmen tried to revive him and, when that failed, they carried him into the speaker's office. He remained there for the next two days, never truly rallying from the stroke.

Members of Congress and the press, who had at their disposal a newly-installed telegraph in the Capitol, eagerly awaited news on Adams's condition. Doctors' attempted treatments were quickly disseminated to the public. And so were Adams's final words before his death on February 23: "This is the last of earth, but I am composed."

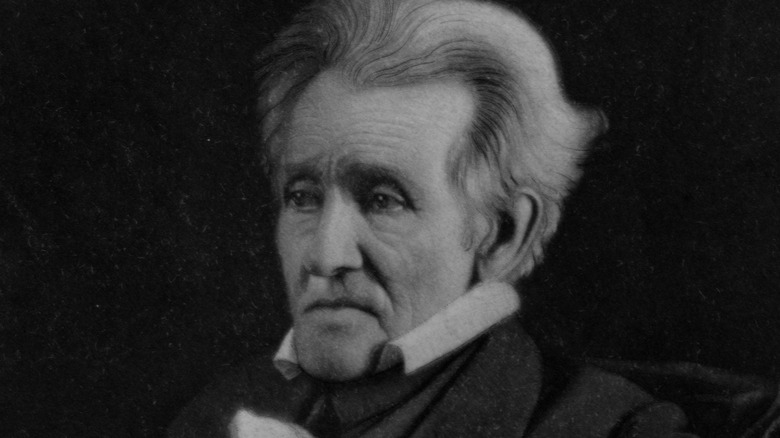

Andrew Jackson

There were several witnesses to Andrew Jackson's death, and they all broadly agree on his last words: some variation of "I hope to meet each of you in Heaven. Be good, children, all of you, and strive to be ready when the change comes." According Mark R Cheathem (via the National Endowment for the Humanities), the variation reported by Jackson's slave Hannah was "I hope to meet you all in Heaven, both black and white." That Jackson would have expressed such a sentiment, and that a slave should have shared it as a tribute to a slaveholder's goodness, can strain credulity with us in the 21st century. But Hannah was a force in shaping Jackson's image for generations of Americans.

In his political prime, Jackson was a deeply divisive figure, revered by large swaths of the population as a heroic democrat and feared and loathed by others as a destructive authoritarian. He was vain, ambitious, and irascible, but he did consider himself a common man and disdained grandiose shows of privilege; he rejected an emperor's tomb brought to America for his burial. Suffrage expanded during his administration, but his policies bred corrosive practices and were devastating for many Black and Native Americans.

Interviewed by biographer James Parton, Hannah, who worked at Jackson' Hermitage estate and may have slept with him, described him as a kind, paternal master, influencing perceptions of the president. But she left unsaid, or didn't observe, the violence shown to plantation workers in the fields.

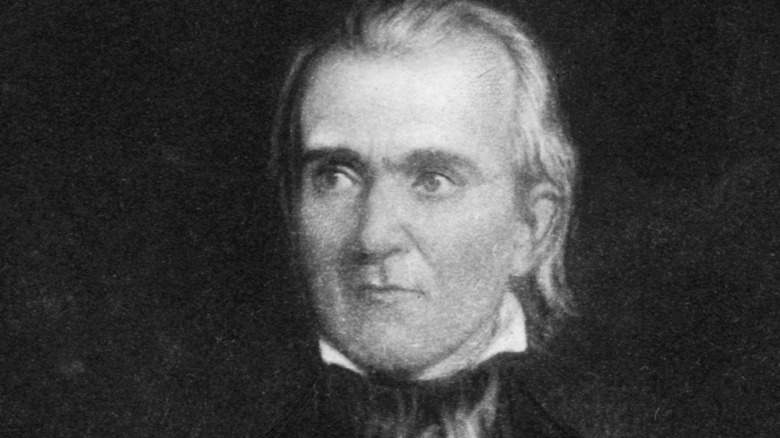

James K. Polk

Romance has not attached itself to the American presidency as an institution, or to many individual presidents, in the way it has the monarchies of Europe. And James K Polk, not the most famous of presidents to begin with, isn't among those with a romantic story that's resonated with his countrymen. But he may have uttered the most romantic last words of any president to date.

Polk's political career was most marked in his own time by his embrace of the idea of America's manifest destiny, a driving force behind the annexations of Texas and Oregon and the Mexican-American War. Posterity has had a chance to see the consequences of his lack of attention to the issue of slavery, especially after the acquisition of so much new territory, all of which have tempered his reputation. His dedication to politics left him with little private life to speak of, but he was a devoted husband to his wife, Sarah.

Per the Polk Home and Museum, Polk and Sarah were touring the south in June 1849, after the end of his time in office, when Polk contracted cholera. He died on June 15, within two weeks of catching the illness and only three months after the end of his term. For how much his political life consumed him, his last words were for his wife: "I love you, Sarah. For all eternity, I love you" (per the Raab Collection).

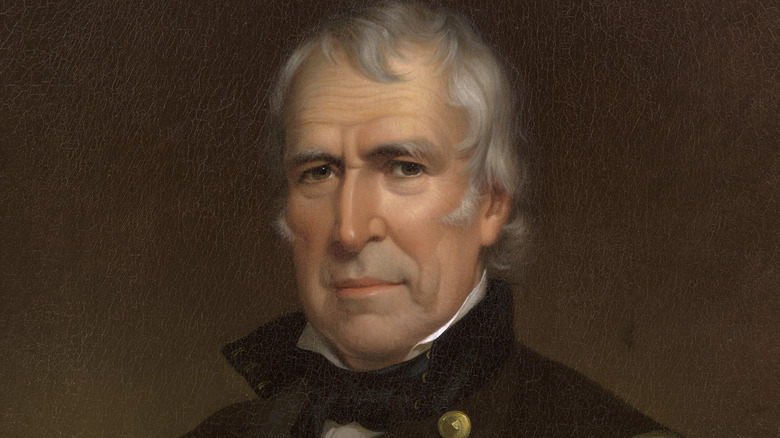

Zachary Taylor

Zachary Taylor's time in the White House was short. A consummate soldier, he was not involved in politics before being elected as a Whig in 1848 and won that election with little in the way of a firm platform or personal campaign activity. This put him out of touch with Congress, and with the tenor of American life as party tensions and the issue of slavery animated the nation. Taylor, a slaveholder himself, indicated an opposition to its expansion in the newly-acquired western territories, making him few friends in the southern states but he still indicated no strong policy agenda before his death.

And death came shortly after electoral victory. Per the UVA Miller Center, he died on July 9, 1850, only 16 months after becoming president. The given cause was "cholera morbus." He was succeeded by his vice president, Millard Fillmore, who delivered the news to Congress. Per The American Presidency Project, Fillmore did not specify Taylor's exact words. He did say that, "Among his last words were these, which he uttered with emphatic distinctness: 'I have always done my duty. I am ready to die. My only regret is for the friends I leave behind me.'" Presumably, those opposed to his suggested antislavery position weren't counted among those friends.

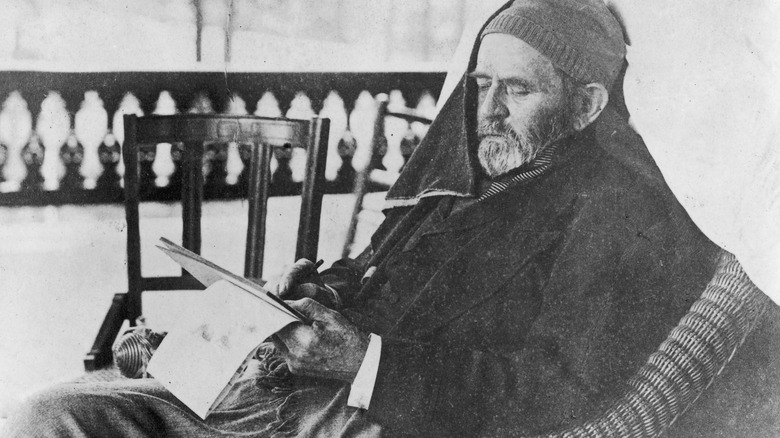

Ulysses S. Grant

It's been said that Ulysses S Grant's last word was "water," but the same book that records him saying so, "The American Nation" edited by James Harrison Kennedy, also says of Grant: "Nothing came from the general before death which could be called his dying words." The request for water, and an earlier answer of "no" when asked if he was in pain, were presented as fleeting whispers in his final hours. Grant was in no condition to utter anything more eloquent; he had been dying of throat cancer for some time, and his voice was almost completely gone by the end.

But if Grant lost his voice in his final months, he didn't lose his way with words. Left financially destitute after poor choices and the wiles of con men did a number on his savings, Grant accepted an offer from Mark Twain to publish his memoirs and leave behind some money for his family. He wrote at a furious pace; his doctors credited his drive to finish the book with keeping him alive even as he lost the ability to eat. Writing also became the easiest way for Grant to communicate with others. In lieu of speaking, he scribbled out quick notes.

It was one of these notes that could be taken for Grant's last words. On July 11, 1885, he wrote, "I feel as if I cannot endure it any longer." Twelve days later, he died. His memoir, completed, was a massive success.

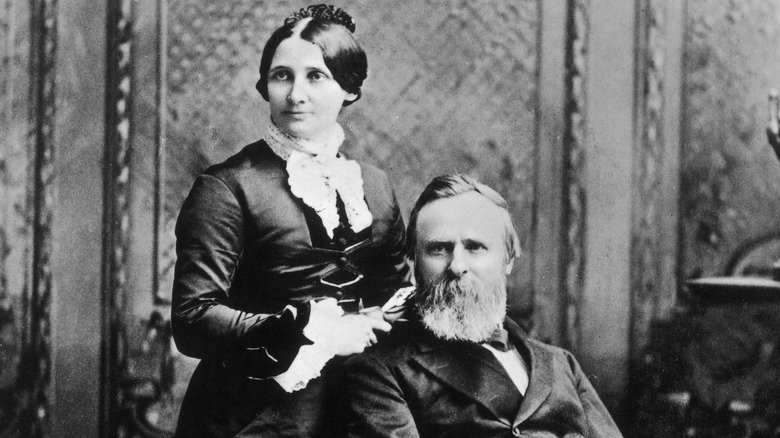

Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford B Hayes didn't expect to become president in 1876, despite being the Republican candidate. The political tide seemed in the Democrats' favor. But while their candidate, Samuel J Tilden, did win the popular vote, a monthslong dust-up over the electoral vote put the election in Congress's hands, and Hayes was delivered to the White House by one vote. Once there, he had the end of Reconstruction and the state of the civil service to contend with, challenges he met to his satisfaction. Later generations have given his administration a more mixed assessment, having seen the long-term consequences. In this, Hayes was not unlike his pre-Civil War predecessor, James K Polk.

Also like Polk, Hayes promised only to serve a single term as president. And both men met their deaths by thinking of their wives. In Hayes's case, his wife Lucy, nicknamed "Lemonade Lucy" for her advocacy of temperance, was a popular first lady and hostess. She and Hayes married in 1852 and had eight children together, five of them reaching adulthood. After leaving the White House in 1881, the Hayeses enjoyed their retirement in Fremont, Ohio.

Lucy predeceased her husband, going in 1889. Hayes wouldn't long outlive her. Suffering from heart disease, he died on January 17, 1893. In the appendix to his published diaries (via the Rutherford B Hayes Presidential Library and Museum), it was noted that he told his doctor just before his death, "I know that I shall soon be where Lucy is."

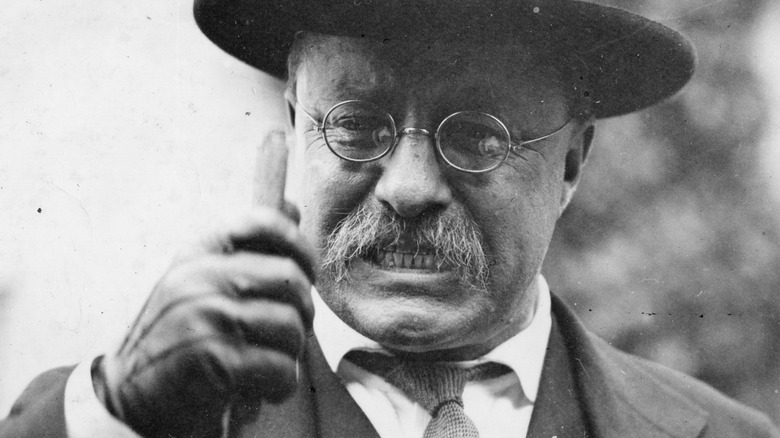

Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt kept his reputation for energetic and combative living until the end. According to the UVA Miller Center, when he finally gave up the ghost on January 6, 1919, at least one member of the press remarked that death could only come for Roosevelt in the night, in his sleep; the former president would've put up a fight otherwise.

The former president was aiming to become the siting president when he died. Having run second against Woodrow Wilson 1912, Roosevelt spent the next eight years criticizing the Wilson administration while advocating for U.S. entry into World War I. The latter cause came back to haunt him when America finally did join the fray. Roosevelt's offer of a volunteer troop was refused by the government, but his youngest son Quentin crossed the Atlantic only to die from German air fire. Despite his grief, Roosevelt continued to campaign for the war, and to lay the groundwork for a run at the Republican nomination for president in 1920.

Roosevelt spent January 5 editing copy for an article tied into his future political plans. Per The New York Times, he was attended by his longtime valet, James Amos. When Roosevelt was ready to retire, he asked Amos, "James, will you please put out the light?" Those were his last words before dying of a coronary embolism.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt didn't have the same reputation for action as his cousin Theodore. But he did succeed where the older Roosevelt had failed; he won a third, and then a fourth term, as U.S. president. Add to that his overseeing of the New Deal and America's entry into World War II, and he had among the most impactive administrations as well as the longest, with his policies and reforms setting the stage for American prosperity for decades to come.

Roosevelt had his own charisma to match his cousin's, encouraging a confident and optimistic outlook and positioning the president as a more forceful presence in the legislative process. But by 1945, his energies were sagging. Even before the 1944 election, Roosevelt's health was in decline, a fact unknown to most voters. After winning reelection and attending the Yalta Conference, he retired to hist cottage in Warm Springs, Georgia, dubbed "the Little White House" by the press.

According to PBS, Roosevelt, who suffered from hypertension and related ailments, hoped to recover in Georgia. But on April 12, 1945, while reading and writing, he complained to his cousin Daisy Suckley, "I have a terrific pain in the back of my head." Suckley summoned Roosevelt's doctors, but there was nothing he could do. By 3:35 PM that day, he was dead.

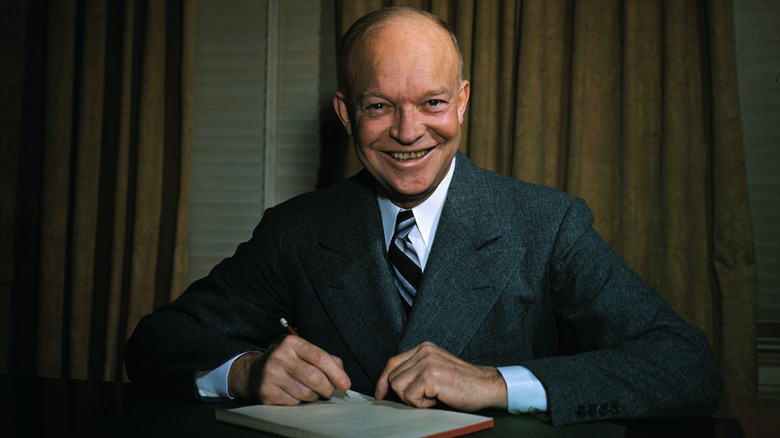

Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight D Eisenhower is more appreciated by historians and political observers now than he was in his own time. He tended to work best behind closed doors, and records of his involvement with the issues of his day were long unavailable. Presented with a sometimes awkward public speaker who often vacationed, Eisenhower's contemporaries might have liked Ike, but they also judged him as average at best as a political leader. But Eisenhower successfully kept America out of new wars, continued the postwar economic boom, and made incremental advancements in civil rights.

After leaving office, Eisenhower continued to play a quiet, behind-the-scenes role as an advisor to his Democratic successors while living on a farm outside Gettysburg. But having suffered a heart attack in 1955, Eisenhower had another ten years later. By 1968, he was a resident patient at Walter Reed Army Hospital, and by March the following year, he was dying.

In his eulogy for Eisenhower, President Richard Nixon shared his predecessor's last words to his wife, Mamie (via The American Presidency Project). "I have always loved my wife. I have always loved my children. I have always loved my grandchildren. And I have always loved my country." But afterwards, Eisenhower took his wife's hand and told his son and grandson (per the UVA Miller Center): "I want to go; God take me." He died on March 28, 1969.

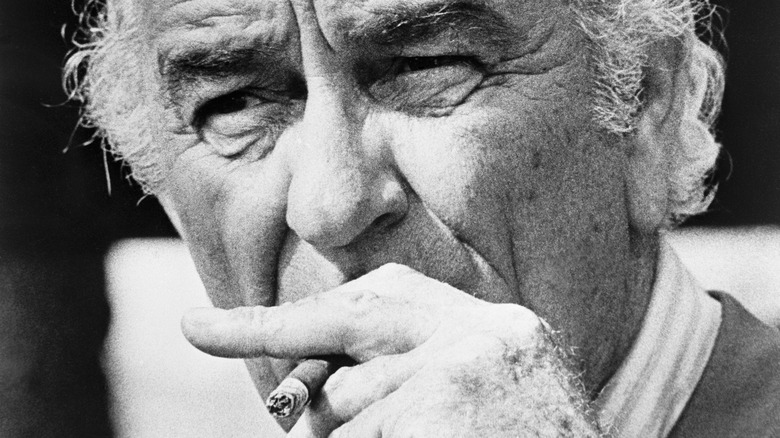

Lyndon B. Johnson

Retirement was a complicated time for Lyndon B Johnson. He'd vowed to enjoy his remaining years when he left the White House in 1969, a decision motivated in part by the life expectancy among men in his family. And he did enjoy himself, sometimes; he played Santa to the families of his ranch workers in Texas, took a hands-on role in the construction of the LBJ Library, and indulged his long-dormant smoking vice, despite the protests of his children. Friends and visitors to the ranch were often subjected to his stubborn schedule and unique "rules" of golf. When a former aide grew his hair out to mark himself off from members of the Nixon administration, Johnson found his inner iconoclast and followed suit.

But Johnson frequently slipped into spells of bitterness in retirement. He was bitter toward the press for how they treated him in and out of office. He was bitter about perceptions of him following the Vietnam War. And he had conflicting feelings about the Nixon administration and his diminished role in Democratic politics. His attitude toward his own life and health turned fatalistic with failing health. "The doctors tell me there is nothing they can do for me," he reasoned (per The Atlantic). "Anyway...[w]hen I go, I want to go fast."

Johnson went on January 22, 1973. Per Time, his last words were a call for help over the phone: "Send Mike immediately." The Secret Service responded, but too late to save his life.

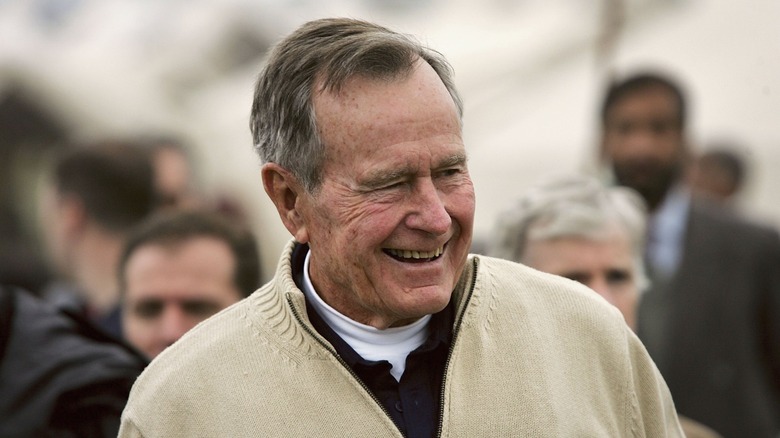

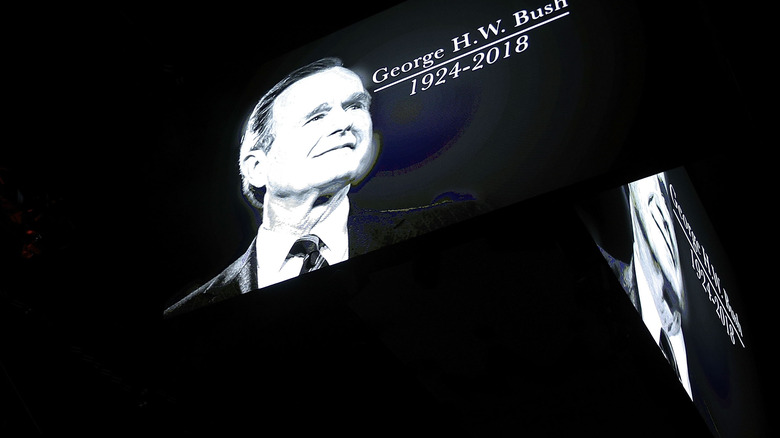

George H. W. Bush

The press, filmmakers, and satirists read a complicated and sometimes resentful nature into the relationship between the two George Bushes. Their presidential legacies were also contrasted. George H. W. Bush, Ronald Reagan's vice president and a long-serving public figure, sought continuity with his predecessor and moved cautiously. He was considered a success in foreign affairs but lost his bid for reelection after an economic downturn back home. His son, George W Bush, enjoyed a full eight years as president, but entered and left the White House under storms of controversy, over the 2000 election, 9/11, the Iraq War, domestic surveillance, Hurricane Katrina, and torture. It's been suggested that the war was motivated, at least in part, by the younger Bush wanting to either avenge a plot by Saddam Hussein to kill his father, or to accomplish the overthrow of Hussein's regime that his father never did (George W denied both claims).

But according to The New York Times, the last words the elder Bush said before dying on November 30, 2018 were with his eldest son. He'd been in declining health for some time, and had told his friend James A. Baker III that he was looking forward to Heaven. On the day he died, Bush was in his Houston home when George W called to say his last goodbyes. When he said that he loved his father, Bush replied, "I love you, too."