The Untold Truth Of The Trail Of Tears

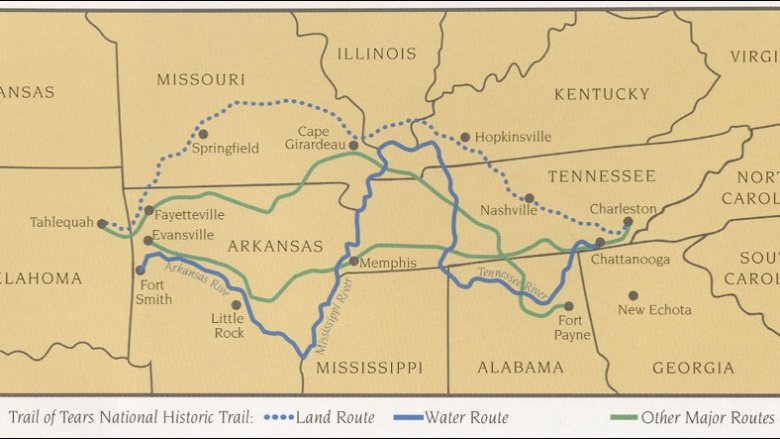

The story of the actual Trail of Tears is pretty simple. Beginning in the 1830s, the Cherokee people were forced from their land by the U.S. government and forced to walk nearly 1,000 miles to a new home in a place they had never seen before. Thousands of people died on the harsh and totally unnecessary journey. It was, quite simply, one of the worst human rights abuses in American history.

But the story around the Trail is incredibly complicated. It involves a decade of buildup, dubious treaties, government legislation, Supreme Court cases, and more. The people involved are equally as fascinating, from real and fake Cherokee chiefs to various presidents to the general in charge of it all. We have gut-wrenching contemporary accounts from Native Americans and soldiers alike. It all comes together to paint a very clear picture of just how something so horrible was allowed to happen. Here are some things you probably didn't learn about the Trail of Tears in school.

It was all because of gold, of course

If historians ever put together a list of "Reasons for Terrible Atrocities," right near the top would be gold. Everyone's favorite shiny thing has caused people to straight-up lose their minds for centuries. You can wipe entire societies off the map as long as you get enough of the stuff.

So it was with the very beginnings of the Trail of Tears. In 1829, a Georgia newspaper announced a ton of gold had been found in the state (via New Georgian Encyclopedia). The northern part of Georgia had been set aside for the Cherokee Nation, but that didn't put off prospectors with dollar signs in their eyes. They poured into the area by the thousands. One participant, writing decades later, said people came from every state, many on foot, and that they acted "more like crazy men than anything else." Even at the time it was known as the "Great Intrusion."

The Native Americans were in these newcomers' way and they were treated like trash because of it. But so much worse would come as a result: the speculators looking to get rich off their land started demanding the government do something about those pesky natives. Less than a year after gold was discovered, President Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act, which led directly to the Trail of Tears.

Then at almost the exact time the last Cherokee were removed on the Trail, the gold ran out.

Andrew Jackson was absolutely despicable

According to the official Cherokee Nation website, Andrew Jackson probably owed his life to 500 Cherokees who came to his aid during a battle in 1814. He would spend the rest of his days being furious about that.

PBS says Jackson called Native Americans "children in need of guidance," and his version of guidance was trying to kill them all. It started in 1814, when he commanded a force against the Creek. Then he attacked the Seminoles in 1818. Over a decade, he was the guy negotiating nine out of 11 treaties with the U.S. that completely screwed the Native Americans over.

As president he pushed through the Indian Removal Act. Then the Supreme Court ruled for the Cherokee in a case, but he just ignored it, because screw checks and balances if it meant being decent to native people. About North Georgia tells us that as rumors of forced removal swirled, a delegation of worried Cherokee came to see him in Washington and he had the gall to tell them, "You shall remain in your ancient land as long as grass grows and water runs."

Even old and out of power he didn't let up. When a small policy change made the second stage of the Trail of Tears a tiny bit less awful for the Indians, he was absolutely furious, but fortunately he wasn't president anymore, so all he could do was yell about it.

The Native Americans absolutely could not win

While the term "Trail of Tears" is generally only used to refer to the forced removal of the Cherokee, they were not the only Native Americans the government evicted during the 1830s. Not by a long shot. According to the Encyclopedia Britannica, about 100,000 people would be kicked out of their homes, and 15,000 of them would die going west. Most of them belonged to the Cherokee, Creek, Chickasaw, Choctaw, and Seminole tribes.

These tribes tried absolutely everything to get the Johnny-come-lately Americans to like them. PBS says they were known as the "Five Civilized Tribes" because they embraced a lot of white people stuff in the hopes of being accepted. This included things like large-scale farming and the Western education style, and some even took up owning slaves. Instead, this made their white neighbors even more pissed off.

Once the Indian Removal Act was signed, these tribes all took different approaches to dealing with it. Some offered to leave their land voluntarily, while others went to war with the U.S. for years in an attempt to stay put. The Cherokee drew up a constitution based on the USA's to prove their rights and even used the Supreme Court to their advantage, winning a major case in their favor. But they never had a chance. No matter what the tribes did, the result was the same, and it culminated in the Trail of Tears.

It had a shaky 'legal' basis

If you ever find someone who tries to defend the Trail of Tears, they will probably point to the fact that, technically, it was all totally legal. Why, the Cherokee themselves signed a treaty saying they would happily get out of Dodge!

By the mid-1830s, it was clear the government was serious about the Indian Removal Act. Other tribes were already being moved either on their own or by force. The Cherokee were debating what to do. Unfortunately, some random guy basically decided for them.

John Ridge (pictured) was a member of the Cherokee Nation, but he represented himself to the U.S. government as the head honcho when he was far from it. According to Today in Georgia History, he signed the Treaty of New Echota in 1835 which agreed to trade all the Cherokee land for $5 million. History says the actual Cherokee chief, John Ross, wrote to Congress explaining their mistake, saying, "The instrument in question is not the act of our nation. We are not parties to its covenants; it has not received the sanction of our people," but the government didn't care. They had a treaty, and they were sticking to it.

It all came back to bite Ridge in the butt, though. In 1839, after the Trail of Tears was well underway and the Cherokee realized just how epically bad that fake treaty had been for their people, a bunch of Cherokee got together and assassinated him.

Not everyone was happy about it

Obviously, the Cherokee were not on board with being ripped from their ancient home and sent on a dangerous journey to the middle of nowhere. After the Treaty of New Echota, over 15,000 of them (virtually the whole nation at that point) signed a petition asking not to be forced to move.

Not all politicians were for forced removal, either. John Quincy Adams (above) had, at best, a mixed record on Native American relations as president, but when he became a Congressman he became seriously uncomfortable with the situation. According to Indian Country Today he called the Trail of Tears "among the heinous sins of this nation." Davy Crockett, Henry Clay, and Daniel Webster all spoke out against it as well. Both the Indian Removal Act and the Treaty of New Echota only barely passed in Congress after bitter debates.

A bunch of random white people were also sympathetic and active against it, especially Quakers and abolitionists. The "ladies of Steubenville, Ohio" petitioned Congress against the practice in 1830, while the poet Ralph Waldo Emerson eloquently appealed to President Van Buren in 1936. According to Sea Coast Online, seven U.S. towns filed "memorials" asking for previous treaties to be honored and Native Americans to stay put. Even many residents of Georgia, specifically the ones who had been around before the gold rush, wanted the Cherokee to stay. While the nation was by no means agreed on the idea, the government wasn't listening.

The guy in charge had good intentions

The lucky guy picked to be in charge of the actual logistics of the forced removal of thousands of people was Winfield Scott. He is widely considered the greatest general of his time: He commanded troops in three major wars and ran for president three times. The giant, embarrassing blot on Scott's resume, that he would definitely not bring up in a job interview, was being in charge of the Trail of Tears.

The journey was never going to be a success, but he really wanted it to go as well as possible, according to Agent of Destiny: The Life and Times of General Winfield Scott. He gave unbelievably detailed instructions to his soldiers about not shooting people who ran away and taking extra care of the ones who were weak or sick. Scott even taught them about some of the high points in Cherokee history so they would have more respect for their prisoners, and guilt-tripped soldiers by saying everyone in America would be pissed at them if they were even a little bit harsh or cruel.

Scott talked with the Cherokee himself and tried to reassure them they would get decent treatment. He listened to the chiefs when they asked him not to travel in the summer due to the ridiculous heat, and encouraged the Native Americans to get vaccinated before setting off. He also sent out messages to settlers along the Trail, asking them to pretty please be nice to the Cherokee as they passed through.

The best laid plans of mice and men

Of course, it didn't work out anywhere near as nicely as General Scott envisioned. Contemporary accounts reveal horrific abuses. One Cherokee who was subjected to the horror later wrote about what happened and sent his writing to the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs. Even before they started walking on the Trail it was horrible, especially if people didn't go willingly:

"For these soldiers were sent, by Gorgia [sic], and [the Cherokee] were gathered up and driven, at the point of the bayonet, into camp with the others. [T]hey were not allowed to take any of their household stuff, but were compelled to leave as they were, with only the clothes which they had on. One old, very old man, asked the soldiers to allow him time to pray once more, with his family in the dear old home, before he left it forever. The answer was, with a brutal oath, 'No! no time for prayers. Go!' at the same time giving him a rude push toward the door. Indians were evicted, the whites entered, taking full possession of everything left."

Once they got underway things got worse. It was winter and most Cherokee had inadequate clothes and blankets. They were herded like cattle, whipped to go faster, and died by the thousands from exposure, malnutrition, exhaustion, and disease. One soldier who was there called it "the most brutal order in the History of American Warfare," saying, "the sufferings of the Cherokees [on the Trail of Tears] were awful" and that it was straight-up "murder."

The forts were even worse than the Trail

As soon as the Indian Removal Act was signed in 1830, forts were built from Georgia to what is now Oklahoma that would "house" the Indians along their journey. You'll notice this was eight years before the Trail began, and even five years before the Treaty of New Echota. But About North Georgia says that's because the government absolutely knew what was coming, even if they played dumb when the Cherokee actually asked them about it.

These were basically concentration camps, and if anything, life was even worse in them than on the actual Trail itself. According to Inside America's Concentration Camps: Two Centuries of Internment and Torture, they were dangerously overcrowded, with small forts holding hundreds of Cherokees at a time. People died every single day. Thanks to the "primitive conditions" many died from the same disease and malnutrition that was killing people when they were walking, but a lot saw no way out of the horror and committed suicide. Soldiers guarding the forts were epic bastards. As if the Cherokee didn't already have inadequate food, clothes, and blankets, the guards stole what little they did have with them. Many also repeatedly violated women and children, along with making them and the Cherokee men perform absolutely unmentionable "acts of depravity."

One soldier who guarded the forts would later write, "During the Civil War I watched as hundreds of men died, including my own brother, but none of that compares to what we did to the Cherokee Indians."

The legend of the Cherokee Rose

Legend has it that to this day we still have a very visual reminder of just how badly the Cherokee suffered on the Trail of Tears. As child after child died, the mothers were overcome with grief. But the chiefs knew that if the moms gave up hope, everyone was completely screwed. Cherokees of California says one night they all gathered together and prayed to the Heaven Dweller (ga lv la di e hi). They explained that things were not exactly going great. They worried that if too many kids died, the Cherokee Nation was finished.

According to Barbara Shining Woman Warren's retelling, the Heaven Dweller replied, "To let you know how much I care, I will give you a sign. In the morning, tell the women to look back along the trail. Where their tears have fallen, I will cause to grow a plant that will have seven leaves for the seven clans of the Cherokee. Amidst the plant will be a delicate white rose with five petals. In the center of the blossom will be a pile of gold to remind the Cherokee of the white man's greed for the gold found on the Cherokee homeland. This plant will be sturdy and strong with stickers on all the stems. It will defy anything which tries to destroy it."

The next morning the mothers looked, and everywhere they had shed a tear, a beautiful, symbolic rose was growing. And they still flourish along the Trail to this day.

'Indian Territory' didn't last long

The idea at the time was that as horrific a human rights abuse as it was, the Trail of Tears was totally going to be worth it for the Cherokee in the end. According to the University of Minnesota, in exchange for very begrudgingly giving up their land in Georgia so prospectors could make a quick buck, an area called Indian Territory west of the Mississippi would be set aside for their use for all eternity. Of course, we now call that same area Oklahoma, so obviously it didn't work out that way.

That's not what people expected to happen at the time, though. Most citizens thought America would stop at the river, a natural end point to the country. The term "manifest destiny" wasn't even coined until seven years after the Trail of Tears started. But it was a shocking short amount of time before there were issues.

After just two relatively boring decades in their new home, the Civil War divided the Cherokee just like the rest of the U.S. and it led to border disputes in the territory. Then in 1887, when the area of the U.S. was engulfing their nation, an act was passed saying they had to purchase the land they had been given by the government. Then oil was discovered, everyone's second favorite thing after gold, and white people started flooding the place. In 1907, Oklahoma officially became a state and the Cherokee Nation was abolished, less than 70 years after they left their homes on the Trail.