What Is The Boy Who Cried Wolf Effect?

You may remember the fable from your childhood. In Aesop's "The Boy Who Cried Wolf," a young shepherd boy repeatedly lies by alerting local villagers that a wolf has come to terrorize his flock. Maybe he does it for attention or just as a childish prank — but either way, he learns his lesson in the end when a real wolf arrives and nobody comes to rescue him.

We sometimes use the phrase "crying wolf" to talk about ordinary everyday liars but it is also a term used by psychologists to pathologize chronic fibbers. According to Psychology Today, the "Boy Who Cried Wolf Effect" is a real psychological term used to describe people who feel compelled to spin out fables of their own, faking crimes against themselves.

Headlines of one such case in July 2023 involved a 25-year-old Alabama woman, Carlee Russell, who called 911 to say she'd spotted a toddler wandering alone near a highway. When police showed up they couldn't find Russell or the toddler, but they located her cell phone, her car, and a wig near where she said she was, per NPR. Once she re-emerged 49 hours later, she claimed she was kidnapped but escaped. She eventually admitted she made the whole thing up and was charged with two misdemeanors.

Sometimes staged crimes are committed out of pure boredom, or as a desperate plea for attention. The Center for Inquiry reports that fake kidnappings in particular are quite common and that they are sometimes used as cover stories to divert attention away from a real crime or other shady behavior.

Famous Fakers

In some cases, a few talented fakers have managed to gain a huge amount of notoriety and press attention thanks to their crafty schemes. In the U.S. for example, the Sherri Papini hoax resulted in a lengthy police investigation. Papini claimed that she had been tortured by two Hispanic women who abducted her and kept her in a closet, branding her with a heated implement. The famous faker went so far as to ask her ex-boyfriend to burn her in order to make the torture look real. After wasting several years of police time, DNA evidence revealed that the strange tale was nothing more than an elaborate fantasy.

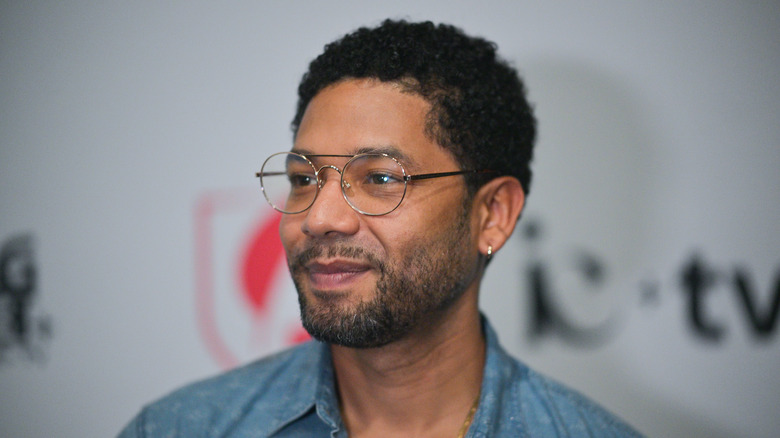

More famous still is the case of actor Jussie Smollett, who decided to continue his acting career off-screen, faking a hate crime against himself as an outrageous publicity stunt. Smollett was convicted for his ruse after it was found that he had paid two brothers $3,500 to attack him in the street in a fake lynching attempt (via The Guardian). It is believed the con was an attempt to boost the little-known actor's career.

Finally, when lawyer Karyn McConnell Hancock faked her own kidnapping, she garnered so much attention prayer vigils were held in her honor (via Center for Inquiry). In reality, however, Hancock was simply experiencing a mental breakdown and had decided to cover up her pain with a tall tale.

Should we rescue the wolf-criers?

Although those who cry wolf might drive us into a fury — especially when they waste resources and divert attention away from real crimes — there is a case to be made that perpetrators are mentally ill and in serious need of medical attention. After all, no healthy well-adjusted person injures themselves on purpose just to get in the news.

To give just one example, one of the creators of the "Satanic Panic" is the U.S. memoir writer Lauren Stratford, who claimed that she had been ritually abused in a satanic cult. However, Stratford turned out to be a seriously delusional young woman whose wounds were self-inflicted (via Pacific Standard). Psychology Today notes that some psychologists recommend that those who cry wolf should be given some form of medical attention, arguing that some people feel so neglected in life they turn to fantasy to get attention.

On the other hand, some gifted liars appear to create hoaxes for purely political ends, supplying fake evidence in support of a cause. Fake hate crimes are quite rare — less than 50 out of every 21,000 cases between 2016 to 2018 were staged according to The New York Times — but they do sometimes happen.