Why 1968 Was An Epic Year For Sports

1968 has gone down in history as one of the most culturally and politically turbulent years ever. Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King, Jr. were assassinated. There were massive student protests all over the world. The Chicago Democratic Convention resulted in bloody clashes between police and demonstrators. The Vietnam War saw the My Lai massacre and the Tet Offensive. Richard Nixon won the presidency. And the U.S. was getting tantalizingly close to winning the Space Race.

But less well-known is that 1968 was also a particularly epic year in sports. Both the Summer and Winter Olympics had historic events. Baseball produced a record-breaking season. Golf saw an epic disaster, the NHL was touched by tragedy, and tennis changed forever. College football had two notable moments, and Sports Illustrated expertly tackled the subject of race. In a year already packed full of stuff, sports refused to be left out of the history books.

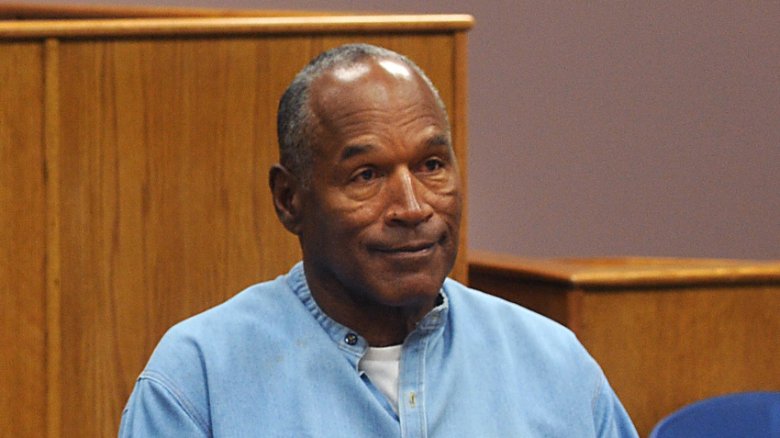

O.J. Simpson won the Heisman

Before O.J. Simpson was totally-not-a-murderer, he was actually a very good football player. And when it came to playing in college, he was 1968's best.

According to the official Heisman Trophy website, O.J. transferred to USC in 1967. There he proceeded to run really quite fast on the football field. That season he led the nation in rushing with 1,543 yards, scored 13 touchdowns, and was a huge part of the reason USC won the national title. But he came second in the Heisman vote that year.

1968 would be different. As a senior he was even more dominant, with 1,709 yards and 22 touchdowns. He carried the ball 334 times, an NCAA record. Absolutely no one was surprised when he dominated the Heisman vote, winning by a record margin of 1,750 points. He went on to be the first overall draft pick for the NFL in 1969, would break a bunch of records, and become an actor. Oddly, the Heisman site completely leaves out the whole murder trial thing.

O.J.'s Heisman would become an issue in 1997. He might have been found not guilty in criminal court, but civil court said he needed to pay the victims' families $33.5 million and he didn't have the cash. So his assets were being seized. But USA Today reported the sheriff's deputies couldn't find the Heisman trophy. O.J. told them to shove it, but in the end it would be auctioned for $250,000 in 1999.

The only NHL player died from an injury sustained during a game

Hockey is a violent sport. When fist fights are a regular and expected part of a game, it's pretty bad. Players wear blades on their feet and pucks are solid little projectiles. But amazingly, only one NHL player in history has died because of an injury sustained during a game. His name was Bill Masterton, and it happened on the ice in 1968.

Masterton had always loved hockey, according to The Star, but he wasn't quite good enough to play in the NHL, so he went and had a regular career outside sports. Then in 1967, the league doubled to 12 teams. Suddenly, he got an offer to play for the Minnesota North Stars. He even scored their first-ever goal. But during one game he took a bad check to the head. He complained of a headache and his face got very red while playing, but he was never sent to a doctor.

While playing his 38th game, he took a routine bodycheck but something went very wrong. Masterton was unconscious before he even hit the ground, and dead 30 hours later. It's now believed he had an existing brain injury, and that final hit was just too much.

His legacy is remembered every year through the Bill Masterton Memorial Trophy, given to the player that "best exemplifies the qualities of perseverance, sportsmanship, and dedication to hockey." This is slightly ironic, since it was his perseverance to playing injured that killed him.

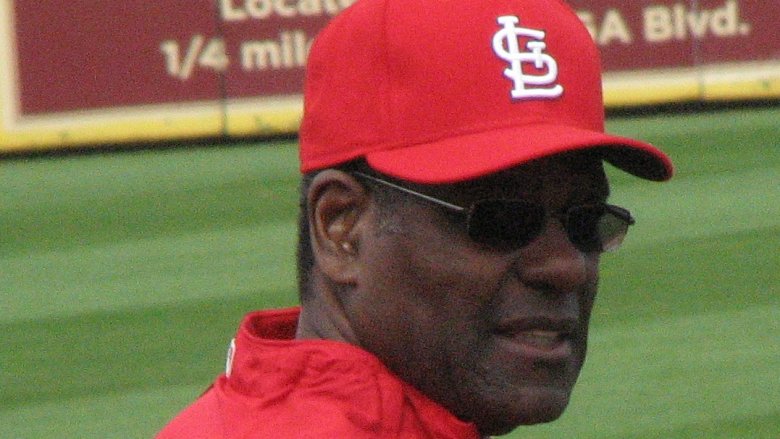

MLB has the 'Year of the Pitcher'

1968 was one of the most epic years for baseball. Newsday says that "by any metrics system" it was "astounding" and that we should all still be marveling at what went down half a century later. One of the catchers who played that year says, "You look back on it and realize what happened, but I don't think anybody went into that season saying, 'Oh, yeah, this is going to be the year of the pitcher.”' But that is how it would go down in sports history.

Bob Gibson of the St. Louis Cardinals (pictured later in life) was a particular standout. He was a former Harlem Globetrotter "with a mean streak to go along with a mean fastball and refined slider." At one point, he won 15 straight games with 10 shutouts and allowed just two runs in 95 innings. Not surprisingly, he would win the Cy Young Award and the National League MVP that year. Gibson wrote in his autobiography, "In 1968, we of the pitching profession came as close to perfect as we've ever come and probably ever will."

But Gibson was far from the only pitcher dominating that year. Denny McLain of the Detroit Tigers also had amazing stats and became the only pitcher of the modern era to win 30 games. Pitchers in general were so ridiculously good that the MLB lowered the height of the mound and tightened the strike zone after that season.

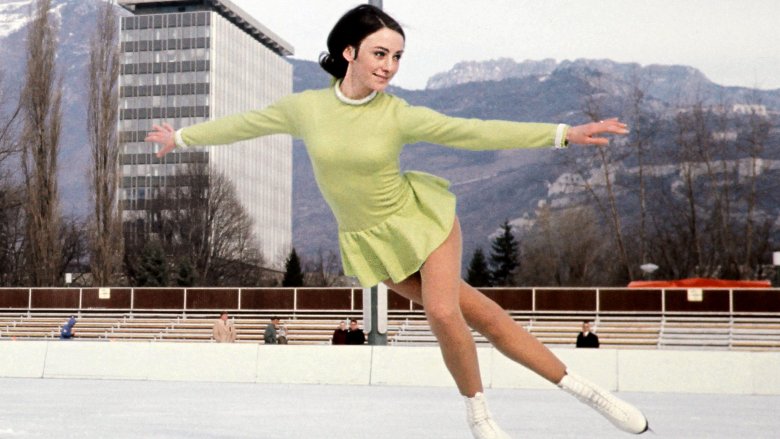

Peggy Fleming changes skating forever

The 1968 Winter Olympics in Grenoble, France are notable for many reasons, according to the Atlantic. West Germany and East Germany both competed, the first time they had been allowed to enter as separate countries. Drug testing for athletes was introduced, as was sex testing for the women's events. And there were some funny moments, like when the bobsled events had to be held in the middle of the night, because the track melted during the day.

But, for the United States at least, the biggest event at the Games was when 19-year-old Peggy Fleming won gold in the women's figure skating. It would be the country's only gold medal of the entire Winter Olympics, and it ushered in the modern era of figure skating.

U.S. figure skating was still rebuilding after a huge tragedy. In 1961, the entire team was headed to the World Championship, when the plane they were on crashed, killing everyone. Fleming's coach was onboard. A memorial fund was set up, and the young Fleming used her portion of it to buy new skates. She would come sixth in the 1964 Olympics, but in 1968 she would dominate.

Fleming's win landed her on the cover of Life. Sports Illustrated would later write that she "launched figure skating's modern era" by taking a "staid sport" and, with a little help from television and a now-iconic costume, would "made it marvelously glamorous." Thanks to Fleming, figure skating is now the most popular sport of the Winter Olympics.

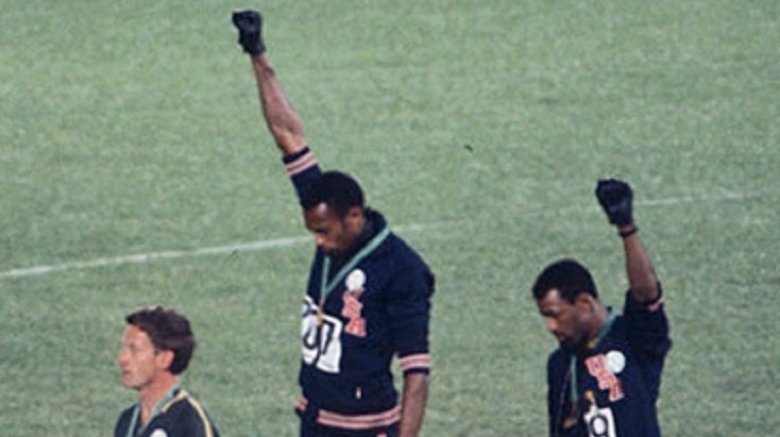

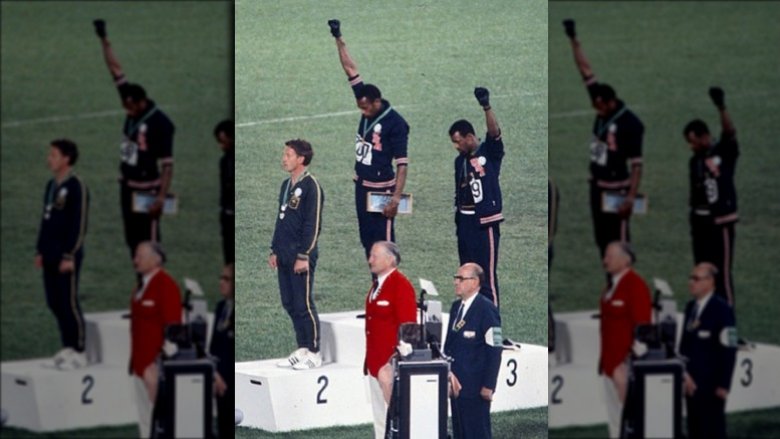

The Summer Olympics saw Black Power

As if the Winter Olympics hadn't been exciting enough, then came the Summer Games in Mexico City. Tragically, just 10 days before the Olympics started, the government massacred up to 3,000 unarmed student protesters. So the Games were already politically charged before they even began, according to History. But they were about to get historically so.

Tommie Smith and John Carlos were U.S. track-and-field stars. They also happened to be African-American, and what was going on in the country at the time deeply affected them. They helped organize the Olympic Project for Human Rights, a group that demanded more jobs for black coaches and rescinding Olympic invitations to countries that practiced apartheid. While Smith and Carlos originally considered boycotting the Games, in the end they decided to go and protest.

They would win gold and bronze, respectively, in the 200-meter race. On the podium, they raised their fists in a Black Power salute. It was an image that would go down in history. Smith said of that moment, "It was a cry for freedom and for human rights. We had to be seen because we couldn't be heard." The third man on the podium, a white Australian, did not raise his fist, but he learned what Smith and Carlos were going to do and asked beforehand how he could support them. They gave him a badge from the Olympic Project for Human Rights to wear.

The stadium erupted with racist jeers and all three men would be severely punished for what they did.

The Fosbury Flop was invented

Less political but still notable things happened at the 1968 Summer Olympics as well. For example, Dick Fosbury completely changed the high jump to what we know today.

According to the Guardian, Fosbury became a high jumper because as a child he really liked sports, but was terrible at all the major ones. He didn't make the football team and despite being really tall was a disaster at basketball. He ended up trying track-and-field, and the thing he was least bad at was the high jump. Even then, it wasn't smooth sailing. In college a friend bet him he couldn't jump over a chair, and Fosbury not only failed, he broke his hand in the process.

At the time, most high jumpers threw themselves over the bar face down. Fosbury had "little success" this way, only clearing 5'4", 23.5 inches short of the world record. So one afternoon he started experimenting. He tried lifting his hips instead, and his heights suddenly started improving hugely. Over two years he perfected what would become the Fosbury Flop.

But no one took him seriously and he only had a world ranking of 61 going into the 1968 Olympics. And then he busted out the Flop. Over four hours in the men's final he cleared bar after bar, until it was at an Olympic record 7'4". He cleared it again and won the gold.

It changed the high jump forever. Since 1972, no one has won a medal using any other technique.

The Masters was decided over an incorrect scorecard

The 1968 Masters should have been slightly more exciting than your average golf tournament. Instead, it is in the history books as a disaster.

Bob Goalby and Roberto De Vicenzo were both going for the win on the final day. In the end, they tied, which should have meant a playoff round the next day. Then the disaster happened. De Vicenzo was distracted and wasn't paying attention when he signed his scorecard. In golf, the person you're playing with keeps your score, and you sign off to make it official. But the Argentinian's partner had made a mistake, marking down a four instead of a three for one hole. The error was caught almost immediately, but the officials decided it stood. According to Desert Sun, the guy in charge said, "You know the rules of golf. Goalby wins the tournament."

De Vicenzo may have lost, but it was really a disaster for Goalby. The media members were obviously against him, and he has said "there were very few stories written the next morning that had it correct. A lot of the stories in the newspaper said I kept his score, I did it on purpose, you know, I took the tournament away from him, to that effect.

Afterward, Goalby received hundreds of letters saying he was "the worst so-and-so that ever lived." He won 11 tournaments in his career, but the 1968 Masters was his only major title, and it was completely tainted.

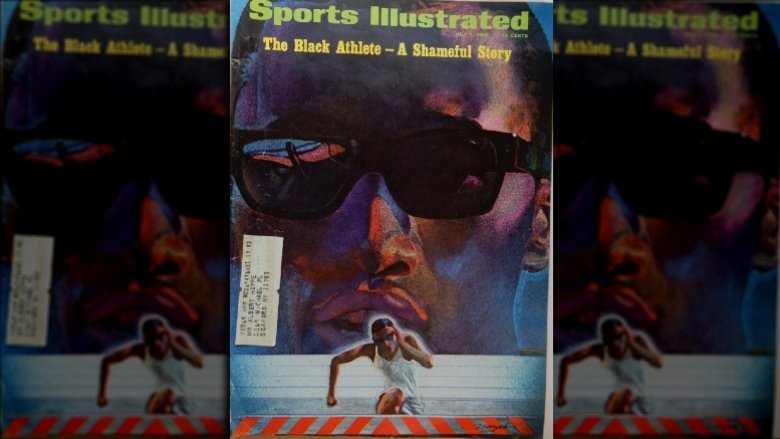

Sports Illustrated covered the history of racial inequality in sports

By 1968, it was impossible to ignore the importance of the civil rights movement. Then Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated. Not even sports could stay separate from what was happening. Saying, "At a time of pervasive racial crisis in America we felt there no longer was room for the complacency that until now has characterized the world of sport," Sports Illustrated began a seminal five-week series called "The Black Athlete — A Shameful Story."

According to the magazine itself, it would become their most famous piece of journalism ever. It questioned the idea that sports were an area of society where black people had found opportunity and equality. Calling this a "myth," the articles quoted coaches who thought they were liberal-minded yet used the N-word to describe their stars. It said that when it came to black athletes "almost to a man, they are dissatisfied, disgruntled and disillusioned. Black collegiate athletes say they are dehumanized, exploited and discarded. ... Black professional athletes say they are underpaid, shunted into certain stereotyped positions and treated like sub-humans by Paleolithic coaches who regard them as watermelon-eating idiots."

An editorial from the time said SI got a bigger reader response than for any other story in their history: 1,000 letters in just a few weeks. While they did get some hate mail or people who refused to accept there was a problem, most people were hopeful. One wrote, "Thank you for jolting me out of dreamland into reality."

The 'Open Era' of tennis started

Tennis.com wants you to know that in 1968, "things got so wild" in the world even the "staid old sport" "channeled the anarchic spirit." That's because tennis finally ended a very distinctive division: the difference between amateurs and professionals.

The sport of tennis had always considered amateurs the better of the two. Starting in Victorian England, it meant you were a "gentleman" who played for the love of the game, not for vulgar money. It was the amateurs who competed in all the Grand Slams: Wimbledon and the Australian, French, and U.S. opens.

Professionals, meanwhile, would play anywhere they could get a paying audience. They would tour around the world trying to make a living. They were talented, but they were shunned. Then they embraced the anarchy of the 1960s and pushed for "open tennis," where everyone played together. In 1968, they finally got their wish.

It happened for the first time at the British Hard Court Championships in Bournemouth, England. They had terrible weather, but 20,000 people came out to watch, twice as many as the previous year. The organizers called it a "bonanza." But many of the top amateurs gave it a miss since they didn't want to hurt their reputations by playing in a "tainted" tournament. Some of the best women's professionals also boycotted because the prize money for the ladies was a fraction of what the men's was, starting that decades-long debate.

In the end the pros would triumph, and the Open Era of tennis began.

The Texas Longhorns invented the wishbone formation

Going into the 1968 season, the University of Texas football team had had three terrible years. ESPN went as far as to say they were "moribund," and Coach Darrell Royal was worried about losing his job. But he was busy holding court in a restaurant near campus, drinking with people like John Wayne, so he tasked an assistant, Emory Bellard, with coming up with an offensive scheme that would see the team actually win some games.

Bellard had been coaching high schoolers two years before, but he took on the challenge. He realized Texas had a "wealth of running backs," so why not capitalize on this and put three rushers in the backfield?

The pressure on Royal to make Texas not suck was so intense that he was willing to "rubber-stamp" the drastic change. The first two games of the 1968 season where they used this new offense were a disaster. But then it clicked, and they won their next 30. A Houston Post writer said the formation looked like a wishbone, and the name stuck.

The wishbone changed college football forever. Texas won back-to-back championships because of it. Other schools that embraced it, like Oklahoma and Alabama, relaunched their football dynasties. Eventually it would "transform offensive football at every level of the game." For two decades, it was the only way to play college football. One coach called it "one of the greatest offenses of all time" and said it is "still having an impact today."