The 1945 Strike That Brought Hollywood To A Screeching Halt

This is the story of the set decorator strike that brought the film industry to its knees. In 1945, two unions were fighting to represent Hollywood's set decorators. It might not seem like the kind of dispute that would turn violent, but it was a time of major change in the film industry, and the competition was more than a dispute over jurisdiction: it was a fight for the future of American labor. One of the unions was extremely large and powerful and was being used as a tool of the mob. Its goal was to exploit its workers by keeping wages low and hours long, in exchange for payouts from the studios. The other was new, radical, and democratically run. There were rumors that its leadership was communist at a time when anti-communist paranoia was running high in Hollywood.

When one union went on strike, it brought the majority of Hollywood to a complete standstill. Soon, the conflict between the two unions would become an all-out war. The American public watched in astonishment as the film industry's behind-the-scenes craftspeople fought in the streets to see which union would rule Hollywood.

The old union had mob ties

Since the 1930s, the entertainment industry's behind-the-scenes craftspeople were represented by the International Alliance of Theatrical and Stage Employees (IATSE). However, the union was not always working in the interest of its members. As described by IATSE, union bosses like Willie Bioff (pictured, right, with his lawyer) were more interested in extorting club and theater owners for money than getting good deals for the workers. Rather than negotiating fair wages and good working conditions, they guaranteed that their members would accept low pay and long hours in exchange for large sums of money. The Chicago gang that was run by Al Capone got involved and brought IATSE to Hollywood. Soon, the studios were making the same under-the-table deals as the theaters and clubs had.

Several union bosses who were working for the mob, including Bioff, were charged with racketeering and spent years in Alcatraz – but their successors Richard Walsh and Roy Brewer continued to run IATSE in the exact same way.

A rival union formed

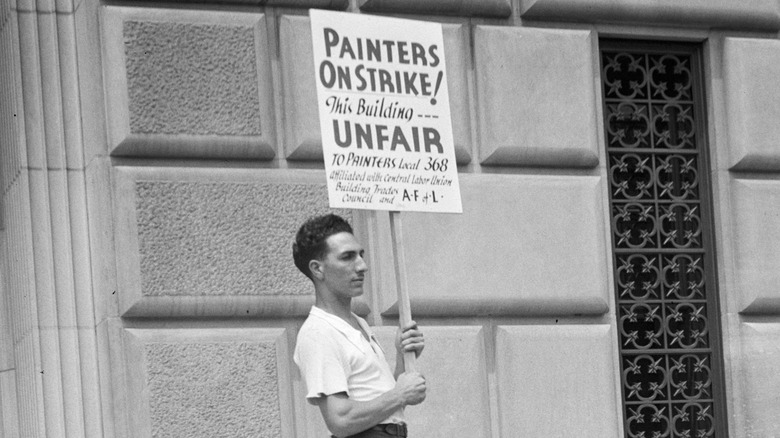

Before IATSE had solidified its hold over Hollywood, a group of 77 set decorators had formed their own small union and made a deal with the studios. As described by Otto Friedrich's book "City of Nets" when IATSE attempted to negotiate a deal for their own set decorators, the studios refused because they had already made a deal with the independent set decorators' union. In 1943, those independent set decorators joined a larger union – but not IATSE. This was a small union for artists and craftsmen like illustrators and cartoonists, known as the painters' union. It was run by a man named Herbert Sorrell, and Sorrell was vehemently opposed to the mob's interference in the unions.

The painters' union and the set decorators' union were not the only ones banding together. Sorrell helped to assemble nine different workers' organizations into one large union of workers with around 10,000 members: the Conference of Studio Unions (CSU). CSU was designed specifically to oppose IATSE. IATSE was still about 40% larger than CSU, but enough workers had joined the new upstart union that they were a legitimate threat to IATSE's control over the industry. The old, established, conservative, and mob-controlled IATSE and the new, radical, workers' rights-focused CSU were poised for a showdown.

Disney cartoonists went on strike

Although IATSE was extremely powerful and backed by a national crime syndicate, CSU's leader Herbert Sorrell had a track record of success going up against powerful adversaries. In 1941, he led the cartoonists in a strike against Disney over unfair wages.

As detailed by animation historian Jerry Beck's Cartoon Research, Sorrell had been doing manual labor since he was only 12 years old and was a lifelong union man. In 1941, Sorrell organized the cartoonists into a walkout and picket line. Animators, including the famous Looney Tunes animator Chuck Jones, reportedly carried a guillotine outside of the studio. It is believed that Walt Disney himself almost got into a physical fight with one of the animators, and 50 private police were hired as strikebreakers to try to disperse the striking workers with violence. A former boxer, Sorrell had no fear of labor strikes turning violent. Ultimately, however, the Burbank police department forced the strikebreakers away from the picket line. The strike garnered lots of public attention, and ultimately, Disney caved to the demands of its animators.

[Featured image by Los Angeles Times UCLA via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 4.0]

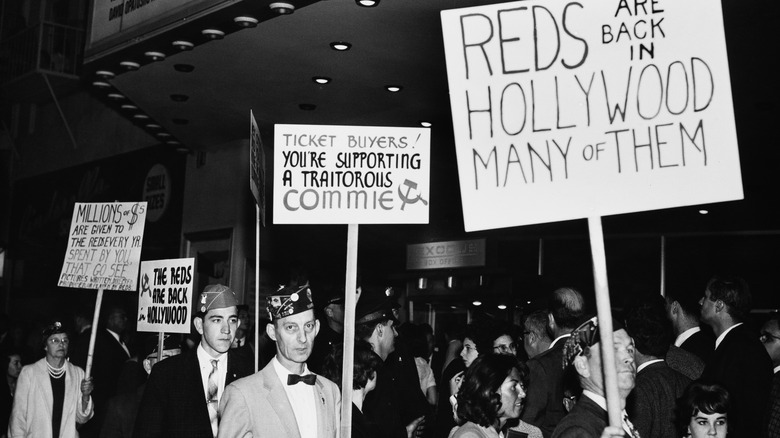

Hollywood Red Scare

With the Disney animators' strike, Herbert Sorrell had earned a reputation as a defender of workers' rights that was not to be underestimated. To IATSE and its conservative leadership, that could only mean one thing: Sorrell was a communist.

The fear of communists infiltrating Hollywood to influence the hearts and minds of the American public was not a new fear, but it became more prevalent in 1939 when Joseph Stalin joined forces with Adolf Hitler. In the 1940s "blacklisting" or preventing anyone suspected of being a communist, having been a communist in the past, or being friends with communists from getting a job in Hollywood, became common. In 1947, the government formed the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) to investigate the film industry and try to force actors, directors, screenwriters, and other Hollywood professionals to confess their political views and accuse others of having leftist beliefs.

IATSE's leader in Hollywood, Roy Brewer was actively trying to push any suspected communists out of their union and viewed CSU and Sorrell in particular as communist agitators. As noted by The Hollywood Reporter, Sorrell himself was not a communist, but he was always willing to take money from communist groups to support his striking workers.

The walkout

In 1945, both CSU and IATSE went to the studios looking for a contract for their set decorators. The studios claimed that it was impossible to choose a side – though as noted in "City of Nets" it is likely that they secretly preferred the more conservative IATSE and its leader Roy Brewer over the militant Herbert Sorrell and his unrelenting desire to secure good contracts for CSU members. On March 12, Sorrell ordered a strike to attempt to force the studios to give CSU's 77 set decorators a contract. It is believed that around 10,500 workers, all CSU members, left their jobs that day. It didn't take long for a few studios, including Disney, to make a deal with CSU, but the majority, including MGM, Paramount, Columbia, and Warner Bros., did not.

CSU's striking members set up picket lines around studios and movie theaters. Soon, Hollywood was forced to take sides. While production continued on many Hollywood films, more than half of all productions were forced to stop. As described by IATSE, stars like Jennifer Jones, Lillian Gish, and Gregory Peck refused to cross the picket lines in solidarity with the striking workers. Peter Lorre single-handedly stopped filming on the noir "The Verdict" because he didn't want to be labeled a scab. Famous writer Dalton Trumbo (pictured, left) actually went to watch the picketing, to ensure the studios didn't try to break it up. Most surprisingly, many of IATSE's members also refused to cross the picket lines, supporting the workers in their rival union.

Black Friday brawl

The strike went on for months, and by October, tensions between the two unions were high. On Friday, October 5th, a crowd of IATSE workers arrived outside of the Warner Bros. studio, planning to work. To do so, they would have to cross the CSU picket line. The CSU workers held firm, and wouldn't let them through. What followed was an all-out battle. Hundreds of workers clashed in front of the studio gates. The resulting fight would come to be known as Black Friday or Bloody Friday.

The two-hour brawl was not only fought by IATSE and CSU workers but also by the police called in to disperse the rowing union members. Union members carried clubs, knives, and broken bottles. Tear gas and fire hoses were unleashed on the crowds. Women workers were also a part of the riot and were reported to be forcing their way through the crowds to bring fresh weapons to their unions. Others participated in the fighting themselves.

It took 300 police officers to make the fighting stop on October 5th. Many were injured or taken to jail, but there were no known fatalities. In the following days, workers from both unions would get into smaller fights, and the police would attempt to break the CSU picket lines to allow IATSE's workers in, resulting in more fights. CSU's Herbert Sorrell (pictured) was often at the front of these brawls and was injured when he was struck in the face with a heavy chain.

[Featured image by Los Angeles Daily News via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 4.0]

They struck a deal, but it didn't last

The studios had believed that given enough time, CSU's strike would fall apart and the easy-to-negotiate with IATSE would take back control of the workers. Black Friday proved that it would not be that easy. The nation was gripped by the story of the fighting in Hollywood. The studios were forced back into negotiations.

As described by IATSE, CSU was officially permitted to negotiate on behalf of the set decorators. Scabs who had been hired to do the jobs of striking CSU workers were given severance pay, and CSU workers were given their jobs back. Many of those scabs had been IATSE members, however, and IATSE was determined to push out CSU workers and replace them with their own members. Although the strike had ended and the famous Black Friday battle was over, the war for control of Hollywood was just beginning. Soon after the deal was struck, IATSE boss Roy Brewer began secretly meeting with the studio executives to discuss pushing CSU members out. Thousands of workers were forced out of their jobs, and by 1946, there was fighting in the streets again.

In 1947, the U.S. government would take action, cracking down on strikes that could stop Hollywood productions. When the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) began investigating Hollywood, they targeted CSU, and Herbert Sorrell in particular. IATSE boss Roy Brewer personally testified that CSU was a communist organization infiltrating Hollywood. By 1952, CSU was no more.