This Theory On The Origin Of Teeth Is Just Nightmare Fuel

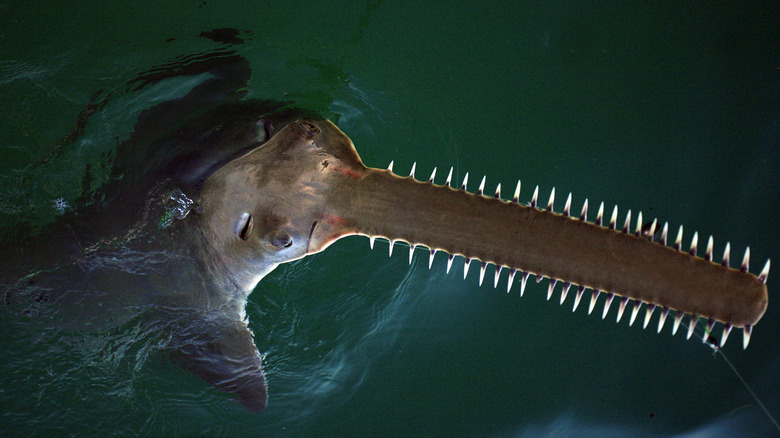

Could the teeth inside our mouths have evolved from scales outside the body, instead? A 2022 study from Penn State University — published in the Journal of Anatomy — supports that hypothesis. No, that doesn't mean hominids — or ancient modern human relatives — had naturally-occurring tooth body armor. Ancient relatives of modern-day sawsharks and sawfish (seen above) — and the now completely extinct sea creature, sclerorhynchoids — did have something called rostral denticles, though: Think spiky, menacing protuberances along their extended snouts.

That information alone is nothing new, but what Penn State University researchers found is that rostral denticles from the extinct Ischyrhiza mira sawfish specifically, which lived millions of years ago, were made up of stuff very much like what modern shark and ray teeth are made from today, according to Scientific American. Is this information a smoking gun proving outside-in teeth truthers correct — the somewhat squeamish notion that teeth, relatively new developments in the natural world, started out as an outside armor-like scale before migrating inside the mouth? (That's opposed to the inside-out theory, or that teeth began in the mouth and then moved outward to become scales and other body coverings.)

Not exactly, but it does show that in the Late Cretaceous period, the jagged-edged stuff lining the outside of some sea animals' mouths was pretty similar to teeth. Most crucially, the Penn State study offers evidence that such an outside-in evolution is even possible, a potential explanation for the evolutionary development of teeth in all creatures — even us.

Fossilized rostral denticles were examined with an electron microscope

Speaking with Phys.org, Penn State associate professor of biology and lead author of the Penn State study Todd Cook said it was once thought rostral denticles had an external morphology and developmental pattern "similar to scales." Otherwise, though, not much was known about how the tissues inside rostral denticles were organized — not to mention the hard outside layer called enameloid.

"Given that rostral denticles are likely specialized body scales, we hypothesized that the enameloid of rostral denticles would exhibit a similar structure to the enameloid of body scales, which have simple microcrystal organization," Cook said. But after examining fossilized denticles with a modern electron microscope, among other methods, researchers discovered that Ischyrhiza mira's enameloid "was considerably more complex than the enameloid of body scales," Cook said.

What researchers found was that "the overall organization of the enameloid in this ancient sawfish resembled that of modern shark tooth enameloid." And these findings provide direct evidence that the outside-in theory of teeth evolution is possible. "[S]cales have the capacity to evolve a complex tooth-like enameloid outside of the mouth," Cook said.

It's possible that similar enameloid structures evolved on both the rostral denticles and shark teeth, but Cook said a more reasonable conclusion is that "scales produced a similar bundled microstructure in teeth and rostral denticles than to conclude that both these structures evolved a similar enameloid independently," and these structures likely evolved to help withstand physical forces involved in feeding.

More study is required to know for certain where teeth came from

Although the Penn State University study goes a long way toward proving the outside-in theory of tooth development in ancient sea creatures — and also possibly for modern humans — more study is required to know for certain, and more questions remain as to exactly how teeth developed in mammals. On the origin of teeth and the evolutionary advantage of biting, Uppsala University paleontologist Per Ahlberg told Scientific American, "If you're feeding, unless you're sucking in really small plankton-type stuff, there are definitely advantages to being able to grab hold of objects in the mouth."

In contrast to the outside-in theory of tooth development, University of Chicago paleontologist Yara Haridy points out that ancient eel-like creatures appeared to have primitive teeth in their mouth, with no scales or denticles on the outside of their bodies — but that's now thought to have been an evolutionary dead end. And while the Penn State University study might explain the origins of teeth, mammals hold one other distinct evolutionary advantage over other creatures: We can not only bite, we can chew.

This chewing gave early mammals a distinct evolutionary advantage, as their diets became more diverse, according to a 2017 study from the University of Chicago's Committee on Evolutionary Biology, published in Scientific Reports. Speaking with University of Chicago News, the study's sole author, David Grossnickle, said, "If you have a very specialized diet you're more likely to perish during a mass extinction because you're only eating one thing."