Groundbreaking Drugs That Changed The Course Of History

It's not every day that you hear about major medical advancements that can really, truly change peoples' lives in massive ways. Of course, the research into those advancements has long been ongoing, but it's always encouraging when the public can see the fruits of those labors.

In fact, exactly that has happened recently; on July 6, 2023, the FDA approved the drug lecanemab (also known by the brand name Leqembi), the first of its class to be effective against early Alzheimer's disease. If it's not already obvious, this is some pretty big news. Alzheimer's is one of the leading causes of death for older adults, and it's something that currently affects millions of Americans alone. Not only that but there hasn't been an effective way to slow the progression of the disease. But now? Not only do researchers have a better understanding of the causes behind Alzheimer's — something that could lead to even more treatments in the future — but those affected by it will have more time before symptoms become more severe. Beyond that, FDA approval should ultimately make it available through Medicare.

Much like how lecanemab will likely pave the way for further advancements in the treatment of Alzheimer's, lecanemab itself comes in the wake of many other drugs that have completely changed history in one way or another. Here are a few of those especially influential drugs.

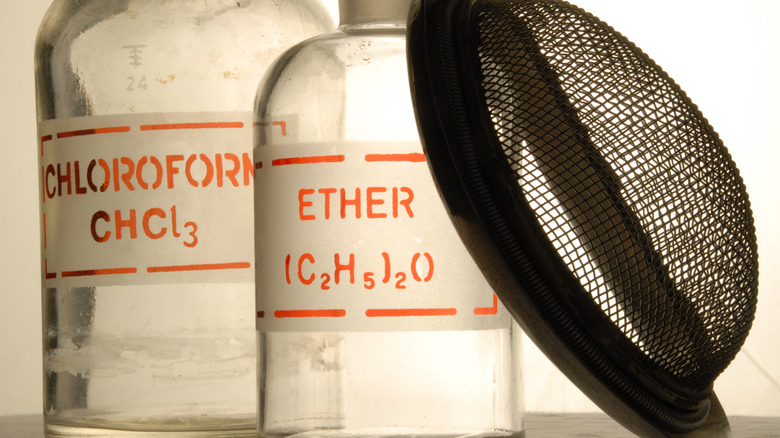

Ether

In the modern day, it's impossible to imagine surgery without anesthetics. Here's the thing, though: Anesthesia is a relatively modern advancement.

Before the mid-19th century, doctors actually just avoided major surgery whenever possible, because attempting it was something of a horrific process. Amputations were done with saws and hot irons, and patients could be heard screaming in agony since the only things they had to numb the pain were primitive at best: ice, alcohol, mesmerism, or other things of that ilk. That said, the answer had actually existed for some time; diethyl ether (known more colloquially as simply "ether") had first been produced back in the 16th century, although it was mostly seen as a recreational substance. The poor would use it in the place of alcohol, and that practice eventually turned into "ether frolics" by the 1800s, in which revelers inhaled its fumes to induce euphoria.

It was those parties that actually led to the advent of modern anesthesia. Crawford Williamson Long attended one such party and, in hindsight, realized that the ether had numbed him to the pain of falls. In 1842, he applied his observations for the first time when removing the tumor from the neck of a patient, and over the next few years, he continued to test his hypothesis. During that time, another doctor, Thomas Morton, ended up stealing the fame for this particular discovery, but regardless, it's hard to overlook just how vital anesthetics have since become for modern medicine.

Aspirin

Aspirin is one of those drugs that everyone's heard of, and that's for good reason. For one, it's a drug that's kind of been around forever; salicylic acid (the natural form of aspirin's active ingredient) was used by ancient civilizations to treat a whole host of different things, from pain and inflammation to fever and hemorrhages. But on top of that, it's also just made people's lives easier by providing accessible pain relief.

Of course, aspirin did have some hiccups along the way. As it turns out, natural salicylic acid isn't great for humans, at least in large quantities, typically leading to a number of different gastrointestinal problems. It wouldn't be until the very end of the 19th century that chemists would find a subtle derivative of the substance that didn't cause those long-term problems, and the Bayer Company's now-famous brand of Aspirin was born. It became commercially available as the first over-the-counter drug, and it even forced doctors to change the way they practiced medicine; if pain could be so easily relieved, then it also wasn't a reliable metric for diagnoses.

But that's not even all that aspirin has done. Starting in the 1970s, aspirin's other uses started becoming more apparent, including a small (but not negligible) decrease in risk for cardiovascular events like heart attack or stroke and some degree of cancer prevention. Those benefits still aren't completely understood and are still being researched, but it seems like aspirin won't be going away any time soon.

Insulin

Diabetes is a condition that people have known about for a very long time, dating as far back as ancient Egypt. Even with that being the case, though, there just wasn't ever any truly good treatment for the condition. Sometimes, physicians would look toward bloodletting or opium, hoping that those techniques would do something. Or there were treatments that focused on various diets, though there was little consensus when it came to the details: Some physicians urged patients to eat more foods, some recommended very specific diets (like low carbohydrate intake but high fat intake), and others believed in extreme fasting (sometimes to the point of starvation). On the side, snake oil salesmen were peddling alternative "cures."

But discoveries made in the late 1800s and early 1900s started changing things, as connections were drawn between the function of the pancreas and diabetes. More specifically, researchers started to realize that the lack of a chemical named insulin was the cause behind diabetes, and within a few decades, there was success both in removing insulin from a healthy animal pancreas and then using it to keep diabetic members of the same species alive. The first human patient to receive a dose of insulin saw a seemingly miraculous drop in blood glucose levels within just 24 hours. Since then, insulin production has become far more efficient, making insulin itself more readily available and allowing people with diabetes to live long lives.

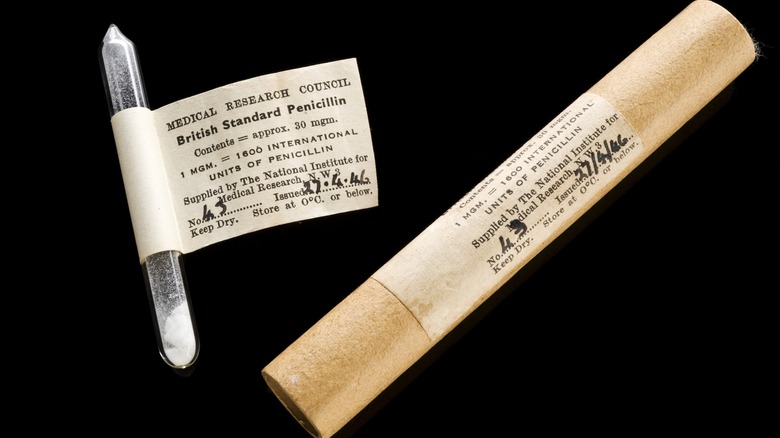

Penicillin

When it comes to medicine, it's really not much of a stretch to say that penicillin is one of the most important discoveries in the field. After all, prior to penicillin, any kind of bacterial infection — whether that be something as major as pneumonia or a simple infected cut — could be a death sentence. It wasn't for a lack of trying; there were just no tools available to cure infections. All anyone could do was hope for the best.

That all changed in 1928 when Alexander Fleming found something strange in a petri dish of staphylococcus bacteria: mold. But more than that, the mold (or, more specifically, the chemical it produced, which Fleming called penicillin) apparently killed the bacteria. The discovery went largely under the radar for years, though, until 1939, when another team of scientists finally gave penicillin a real chance. Over the next few years, penicillin was properly purified and tested on animals, with the first human trial occurring in 1941. That trial showed major promise, with penicillin treating a life-threatening infection, though that same trial also revealed another major problem: the shortage of available penicillin. The problem wouldn't really be solved until the mid-1940s, at which point the military took an interest due to World War II. In the years after the war, though, penicillin became publicly available, introducing people to the powers of antibiotics for the first time.

[Featured image by Wellcome Images via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY 4.0]

Chemotherapy drugs

The journey toward the discovery of chemotherapy drugs is honestly pretty strange and unexpected. After all, the medical field is still trying to answer the question of how to finally cure cancer, so it might be a bit unexpected to learn that chemotherapy has its roots in chemical weapons research during World War II.

You've probably heard of mustard gas. Well, when World War II rolled around, the U.S. started conducting research on mustard gas and its related compounds, one of which was something called nitrogen mustard. As it turned out, this chemical ended up changing white blood cell counts in those who had been exposed to it, and that led to a new question: Could nitrogen mustard be used to treat cancer? After all, cancer cells rapidly multiply, and nitrogen mustard apparently lowered cell counts.

The study of chemotherapy took off from there. Researchers began using diluted versions of it to treat non-Hodgkin's lymphoma — a process that did prove at least somewhat effective, reducing the size of tumors, even if not permanently. Similar drugs (called alkylating agents) were shortly discovered, as was a particular derivative of folic acid, both of which controlled cancer by affecting the DNA of cancerous cells — either destroying it or stopping it from replicating, respectively. Compared to prior treatments, which included radiation and the physical removal of tumors via surgery, all of this was both promising and attractive, with reports of remission finally coming in the 1950s.

Chlorpromazine

To say that the history of mental health treatment is messy is quite an understatement. After all, it's a topic that's still in the process of receiving the proper attention in the 21st century, and when you look back at the past? Well, the typical picture of mid-20th-century asylums is a deeply disturbing one, and historically, the treatments for conditions like schizophrenia often included procedures like lobotomy or electroshock therapy.

It doesn't really need to be said just how awful that is, but fortunately, during the 1950s, things finally started changing. While trying to synthesize an antihistamine, a French pharmaceutical company ended up stumbling on the drug chlorpromazine, which was found to induce a state of calmness in those who took it. Focus shifted with that discovery, and scientists hypothesized that the drug would actually have a big impact on psychiatry. Asylums took to the drug quickly, finding that it could stop hallucinations — an effect that also ended up allowing patients to rejoin wider society.

As the 1950s progressed, chlorpromazine, sold under the brand name Thorazine in the U.S., was prescribed more and more widely, and the deinstitutionalization movement came into full swing, with asylum populations dropping sharply over the following decades. The discovery of chlorpromazine actually prompted research into antipsychotics. With chlorpromazine as a starting point, more research went into the mechanisms behind conditions such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, as well as the synthesis of drugs that could provide better treatment with fewer side effects.

Thalidomide

Just to be clear, the Thalidomide Scandal was a tragedy, and that's something that can't be overlooked. But if you're not familiar with it, here's the gist: In 1956, a German company named Chemie Grünenthal put a new drug out on the market. That drug was called thalidomide, and it was meant to be used as a sedative, though it actually became known and largely used as a treatment for morning sickness. But over the course of a handful of years, thousands of babies were born with major birth defects like foreshortening of limbs and underdeveloped organs in some cases. Thalidomide was pulled from the shelves and reassessed, but the effects of the event have still lingered.

Thalidomide's negative effect on history is pretty clear. That said, the drug had other effects that weren't necessarily as negative because tragedy can inspire change. On one hand, there's regulation. A lot of this was catalyzed by the fact that thalidomide hit the market with pretty minimal testing and a lot of dangerous assumptions regarding safety. Afterwards, drugs required far more rigorous testing and documentation proving their safety, and the FDA was given a lot more authority.

When it comes to pharmacology and biology, thalidomide's flaws actually prompted further research. It became clear that understanding exactly how thalidomide interacted with the human body could lead to the development of drugs that didn't produce similar side effects. That same understanding could improve how we understand limb development in human embryos.

Birth control

The introduction of the birth control pill (and its growing availability) throughout the mid-20th century changed a lot, and not just for the medical field — far from it. Of course, there are notable side effects that have little to do with contraception — like protection against various kinds of cancers, for example (via Contraception) — but it's the social effects that are perhaps most striking.

Prior to the 1960s, the possibility of getting pregnant after sexual activity was much higher than it is now; other types of contraceptives did exist, but their chances of failure were not insignificant. And that dictated a lot when it came to women's lives and opportunities. Generally speaking, it was hard for women to pursue careers because a sudden pregnancy could really throw a wrench in those plans. After the introduction of the birth control pill, though? Well, in the U.S., as early as the 1980s, more and more women were taking their places in higher education, earning advanced degrees, and finding work in professions like law or medicine. Generally speaking, women had a lot more control over their bodies and lives, no longer needing to choose between marriage (and motherhood) and their careers.

Interestingly enough, the introduction of the birth control pill in the U.S. also happened to align with a bunch of other social changes, including the women's rights movement, new views on sexual relations, and the trend of couples marrying and having kids at an older age.

Idoxuridine

When it comes to medicine and pharmacology, there isn't just one kind of drug, and not all drugs are exactly created equal. One of the big distinctions between drugs is what they target — like bacteria or viruses, for example. And, in general, viruses have been significantly harder to target; given that they take up residence inside host cells and use them to multiply (via International Journal of Immunopathology and Pharmacology), antiviral drugs can actually hurt not only the virus but also its host. Therein lies the problem, as well as the reason there are just fewer antivirals compared to antibiotics.

That's where the drug idoxuridine becomes something of an interesting case. The history of the drug itself isn't incredibly complex, having been synthesized in 1958. That said, it was initially intended as a chemotherapy agent, but researchers eventually found that it could fight against a particular strain of herpes. It got its FDA approval a few years later in 1963 but has seen less and less use as time has gone by, given that newer antivirals have simply outclassed it (via Frontiers in Microbiology).

All the same, though, it's worth noting that discussions of antivirals often point to idoxuridine as being the starting point, kicking off further development of many more drugs like it — a group that includes treatments for conditions ranging from the flu to HIV. That's quite the legacy.

AZT

When it comes to the second half of the 20th century, it's hard to argue against the impact of the AIDS crisis. The discovery of AIDS (and HIV, the virus which causes it) in the early 1980s led to both public panic as well as widespread discrimination. Doctors could be evicted from their homes for treating people with the virus, children were barred from attending schools if they'd been diagnosed with it, and negative associations were drawn between AIDS and the gay community.

Doctors were scrambling as the number of AIDS diagnoses and deaths began to rise because they knew things would only get worse without a solution. Pharmaceutical companies began testing anything that they could get their hands on, hoping for a miracle. And they found one: azidothymidine, or AZT, a forgotten, failed attempt at cancer treatment. Early animal testing proved very promising, and it was rushed into clinical testing on human patients which, again, seemed successful. AZT truly seemed to be the miracle drug everyone was hoping for.

Now, it's worth noting that, by modern standards, the whole process was rushed and the results of those trials can be debated. (Outside factors weren't considered or controlled for, and patients likely shared their treatments amongst themselves.) Nor was AZT the perfect miracle; it has some pretty nasty long-term effects. But nonetheless, it provided hope at a time of crisis — something that can't be ignored — and laid the groundwork for the dozens of treatments that exist today.