Athlete Deaths That Changed Sports History

When we talk about athletes who transformed their sport, we tend to think of greats like Babe Ruth or Muhammad Ali, people who won championships, set records, and captivated the masses with their exhilarating abilities and larger-than-life personalities. But some athletes have changed the face of sports because they paid the ultimate price to compete. They died during sporting events, succumbed to years of brutal injuries, or pushed themselves to fatal extremes while preparing for a match. These athlete deaths not only shocked and saddened the sports world, but forced it to take stock and evolve.

Obviously, it's impossible to eliminate risks from sports altogether. But just as coaches push athletes to be the best versions of themselves on the field or in the ring, officials should push to ensure that athletes play in the best version of their sport. Because when competitors systematically destroy themselves for a chance at glory, that doesn't promote athletic ideals; it causes needless suffering and detracts from the magic of competition. Here are athlete deaths that changed sports history.

Harold Moore's death led to the creation of wide receivers

1905's version of American football was a different, deadlier animal than what fans watch today. As Deadspin explained, there was no forward passing, no neutral zone separating the offense and defense, and you only needed 5 yards for a first down instead of 10. Teams chaotically smashed into each other like cars at a demolition derby, and kicking and punching were permitted. If you're wondering what the pads and helmets were like, there weren't any.

Between 1900 and October 1905, no fewer than 45 football players died, according to the Washington Post. Many of them sustained broken backs, internal injuries, and severe concussions. The Chicago Tribune called the 1905 season a "death harvest." An estimated 20 players died, including a high school student whose heart was pierced by his own broken rib. The public finally had enough when Union College halfback Harold Moore suffered a cerebral hemorrhage after getting kicked in the head.

Moore's death prompted some universities to halt their football programs, and Harvard's president spearheaded a campaign to ban the sport. However, President Teddy Roosevelt (above), a Harvard alumnus whose son also played football for the school, worked with university coaches to make the sport safer. To prevent players from fighting over the ball in giant heaps, forward passing was introduced, effectively inventing wide receivers. Teams were also allowed to kick the ball downfield, and the game paused when someone fell on the ball. The changes didn't fix everything, but they fixed a lot.

Boxing's 'championship distance' ended with Duk Koo Kim

In boxing, championship fights used to have three extra rounds, bringing the total to 15. That's an incredibly long time to get punched by a world-class fighter, and boxers lasting through the entire bout often earn respect even if they lose. Heck, that's the plot of the first Rocky movie, which Sly Stallone wrote after Chuck Wepner lost to Muhammad Ali by technical knockout in the final 19 seconds in their championship fight. But braving an onslaught of ferocious blows doesn't always result in beloved movie characters. In Duk Koo Kim's case, it left a trail of death that stunned the boxing world.

Per ESPN, Kim was "wrongly named the No. 1 contender in the world for the lightweight title." Largely untested and utterly outmatched, he didn't stand a chance against the champion, Ray "Boom Boom" Mancini. Throughout their 1982 bout, Kim took a hellacious beating, with Mancini landing "40 unanswered shots" in the 13th round alone. But the challenger refused to back down, swinging wildly in a doomed effort. The referee stopped fight in the 14th round, but Kim soon fell into a coma and passed away five days later. In the aftermath, Kim's mother committed suicide, as did the referee from the fight. Boxing officials determined that championship distance (rounds 13 through 15) killed Kim. In response they shortened title bouts to 12 rounds.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

Ray Chapman's death ushered in a new era of baseball

Nowadays a spitball is just a slobbery wad of paper you launch at unsuspecting teachers. But in 1920 it was an extremely hazardous but nonetheless legal baseball pitch. As the Houston Chronicle detailed, pitchers used to coat balls with mucus, petroleum jelly, or (obviously) spit, causing them to travel erratically through the air. (Alternatively, pitchers would scuff balls or cover them with mud.) One of baseball's most infamous spitballers was New York Yankee Carl Mays.

When Mays pitched, he resembled "a cross between an octopus and a bowler," per Smithsonian Magazine. After one of his throws killed Cleveland Indians shortstop Ray Chapman, two umpires would remark that "No pitcher in the American League resorted to trickery more than Carl Mays." Graphic novelist Molly Lawless has disputed the claim that Mays threw a spitball, but whatever he threw made a 3-inch dent in Chapman's skull. Chapman, who wasn't wearing a helmet, reportedly never saw it coming.

The athlete's death had a ripple effect on baseball. Spitballs were formally banned, and umpires were instructed to keep only white clean balls in play to maximize visibility, making them easier to hit. According to the MLB's official historian, this helped usher in the Live Ball Era, when batting averages rose and Babe Ruth dominated. That era also saw the ascent of Joe Sewell, who replaced Chapman in Cleveland and became a Hall-of-Fame shortstop known for rarely striking out.

Knud Jensen ignited the Olympics' anti-doping movement

Doping scandals have literally rewritten Olympic history. In 2016 Usain Bolt, the first person to win the 100 m, 200 m, and 4x100 m races at three straight Olympics, had to relinquish one of his nine gold medals because one of his teammates used a performance-enhancing drug. In 2018 Russia was barred from the Winter Olympics due to widespread doping. A few Russian athletes were deemed eligible to compete under the Olympic flag, and none of their 17 medals counted toward Russia's official tally.

Decades ago, things were a lot different. In fact, prior to 1967 the Olympics didn't even have a list of prohibited substances. According to Newsweek, organizers decided to crack down on doping after Knud Jenner died at the Rome Games in 1960. Jensen toppled to the ground during a time trial for the 100 km cycling event and expired an hour later. The tragedy was initially blamed on heat stroke, but Jensen's coach admitted giving the cyclist Roniacol, which boosts blood flow. The Sports Integrity Initiative reported that although heat stroke was the real culprit, Jensen would become the official face of the anti-doping movement.

Mike Webster's demise triggered the NFL's concussion controversy

With four Super Bowl rings and nine Pro Bowls to his name, "Iron" Mike Webster was one the greatest Pittsburgh Steelers in franchise history and an all-time great NFL lineman. But after his Hall-of-Fame career ended, his mind declined rapidly. As Concussion author Jean Marie Laskas detailed, Webster began sleeping under bridges and accosting strangers outside. He urinated in his oven, and when his teeth fell out, he superglued them back into his mouth. In 2002 Webster died of a heart attack, which doctors partly attributed to depression caused by post-concussion syndrome.

Neuropathologist Bennet Omalu examined Webster's brain and discovered what would become known as CTE (chronic traumatic encephalopathy). The NFL unsuccessfully attempted to suppress and discredit Omalu's findings but eventually had to admit that repeated concussions had devastating effects on players. Safety concerns, awful PR, and lawsuits led to multiple reforms. In 2010 the league announced that dangerous hits would be punishable by suspension. In 2018 it banned six different kinds of helmets that failed impact absorption tests.

The NFL's concussion safeguards have altered player behavior, but some question whether all the changes are positive. Fear of being penalized for helmet-to-helmet hits has caused some players to tackle opponents at the knees, which can result in career-ending knee injuries and other season-ending tackles.

Wrestling cleaned up its act after three athletes died within weeks of each other

For a long time wrestlers believed "the secret to success lay in dropping to lower weight classes" at all costs. Per the NCAA website, weight-obsessed mat grapplers tried to torture every ounce of fat and water out of their bodies to avoid facing heavier opponents. They denied themselves meals before matches, exercised furiously while wearing suffocating rubber or plastic suits, and tried to sweat their pounds away in saunas.

Wrestlers especially tried to shed water weight, the logic being that they could replenish themselves after the weigh-in and have an edge over smaller opponents. Coaches preached that those who suffered more would succeed more. But in November 1997, collegiate wrestler Billy Saylor suffered so much that his heart failed. He had lost 23 pounds in 10 weeks and was trying to lose 15 more. Two weeks later, another college wrestler, Joe LaRosa, died from overheating while pedaling on an exercise bike in a rubber suit. In December, Joseph Reese's kidneys failed after he lost over 15 pounds in four days. He, too, was riding an exercise bike in a rubber suit when his body gave out.

To the chagrin of old-fashioned coaches, in 1998 the NCAA rolled out new policies to ensure competitors weren't starving or dehydrating themselves. Weigh-ins occurred closer to matches, and a seven-pound weight allowance was added to discourage excessive weight-cutting. Later, body fat and hydration checks were instituted. Overall, it's been a success story.

NASCAR insisted on safety precautions after Blaise Alexander's deadly crash

ESPN contributor Ed Hinton called the night Dale Earnhardt died "the darkest night in NASCAR history." On February 18, 2001, Earnhardt veered into a wall during the last lap of the Indy 500. Amid the gloom Hinton saw a silver lining, claiming the heart-wrenching loss may have "saved" NASCAR by bringing about life-saving reforms. While that's a widely accepted narrative, Patriot-News writer Stephanie Loh underscored that NASCAR's added precautions remained optional until Blaise Alexander's fatal crash.

Although Alexander wasn't a NASCAR driver, he drove for the ARCA, which the Sun-Sentinel described as a "closely allied" organization. "Blaise was a pure racer," said NASCAR's Hall of Fame historian, Buz McKim, who believed the driver "was going to be something special." But on October 4, 2001, Alexander's promising career was cut short. Alexander was in a tight race with the late Dale Earnhardt's son Kerry. At some point, their vehicles touched, and Alexander slammed headlong into a wall. Like Dale Earnhardt, Alexander sustained a basilar skull fracture.

Howard "Humpy" Wheeler, who presided over the raceway where it occurred, was outraged and publicly pressured NASCAR to require head and neck restraints for drivers, which it did. To head off a potential lawsuit, Wheeler also promised Alexander's father that he'd get NASCAR to adopt impact-reducing barriers at every NASCAR track. In the years since, NASCAR hasn't had a single fatal crash.

The NHL requires helmets because Bill Masterton didn't wear one

Bill Masterton played just 38 games in the NHL, but he changed the course of professional hockey. A lifelong hickey fan, he joined the NHL in 1967. Unfortunately, he competed for the Minnesota North Stars at a time when helmets were deemed unmanly. According to the journal Neurosurgical Focus, "fewer than 20 players in the NHL wore helmets," and Masterton wasn't among them.

In his short career Masterton endured a series of skull-rattling hits that caused him to experience migraines and to black out during practice. Already showing signs of brain trauma, he would lose his life during a 1968 game when an opponent checked him so hard that his brain rotated in his head. He also fell backward, smacking his unprotected cranium against the ice. Masterton's final words were "Never again, never again."

In the wake of Masterton's death, NHL officials debated requiring players to wear helmets, and for the first time ever, the league officially voted on the matter. However, three separate attempts to mandate headgear failed. Per the Chicago Tribune, owners feared that covering players' heads would render them unrecognizable and hurt hockey's popularity. Despite initial pushback, attitudes slowly changed, and in 1979 the NHL finally required the use of helmets.

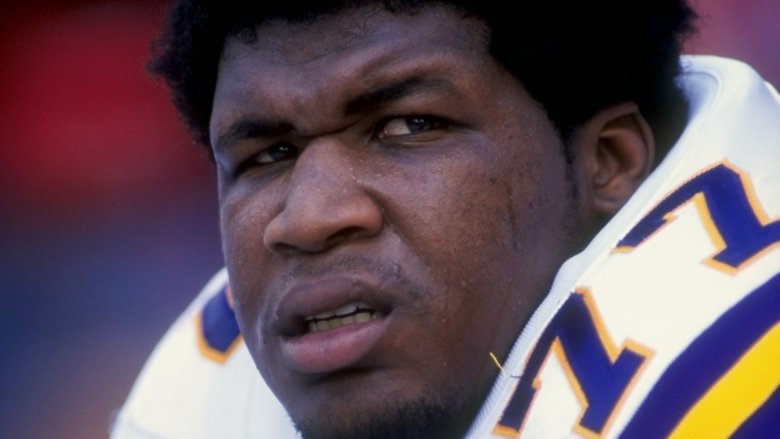

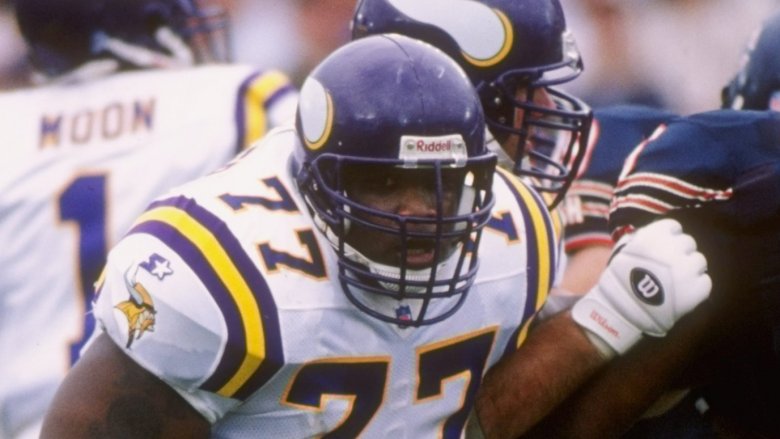

Korey Stringer changed how the NFL thinks about heat stroke

There was a time when most NFL players wouldn't have dared to ask for Gatorade or ice while practicing in sizzling heat because showing vulnerability was a no-no. And if a player felt especially parched, a coach would usually tell them to swish water in their mouths and spit it out because actually drinking it might cause cramps. However, Korey Stringer changed all that.

At age 20 Stringer became "one of the youngest players ever drafted," according to Bleacher Report. He made his NFL debut in 1995 as an offensive tackle for the Minnesota Vikings. In 2000 he played in the Pro Bowl. The following year he died. It happened on a blazing hot day in July. The Vikings practiced for over two hours, and then the coaches ordered the offensive line to do "extra work." Stringer had already struggled through the first workout, but he was told to "suck it up."

Stringer's core temperature would rise to a lethal 108 degrees. Teammates recalled him buckling on the field, then stumbling and eventually passing out. The incident convinced the NFL to start taking heat stroke seriously, and according to ESPN, the Minnesota Vikings led the effort. Players are now urged to stay hydrated and sometimes even swallow pills that track their internal temperature. Stringer's story also inspired the University of Connecticut to found the Korey Stringer Institute, which spreads awareness about heat stroke to schools across the country.

Ben Robinson inspired an entire nation to change

In 2011 a crowd of spectators in Carrickfergus, Northern Ireland, watched the end of a teenager's life unfold before them. During a rugby game at Carrickfergus Grammar School 14-year-old Ben Robinson suffered three separate blows to the head. In each instance the coach performed a crude check for concussions by waving his fingers in front of Ben's face, and each time he concluded the teen was fine. Ben's mother disagreed. Watching from the audience, she could tell her boy was in serious trouble, but as The Guardian detailed, the referee dismissed her worried cries.

Soon other spectators yelled at the ref to stop the match, but it was too late. Ben, who'd become increasingly unsteady, completely lost consciousness. A coroner later determined that the athlete died from second impact syndrome, a condition caused by repeated strikes to the head which can result in lethal brain swelling. Because of his age, Ben's brain was especially susceptible. It marked the first known instance of a rugby player dying from second impact syndrome in the U.K.

In the years that followed, Ben's father became a powerful voice for change. He advocated updating concussion guidelines in U.K. schools, and Scotland listened. Per the BBC, in 2015 Scotland became "the first country in the world to introduce standard guidelines for dealing with concussion in sport."