Famous People Who Were Almost On The Titanic

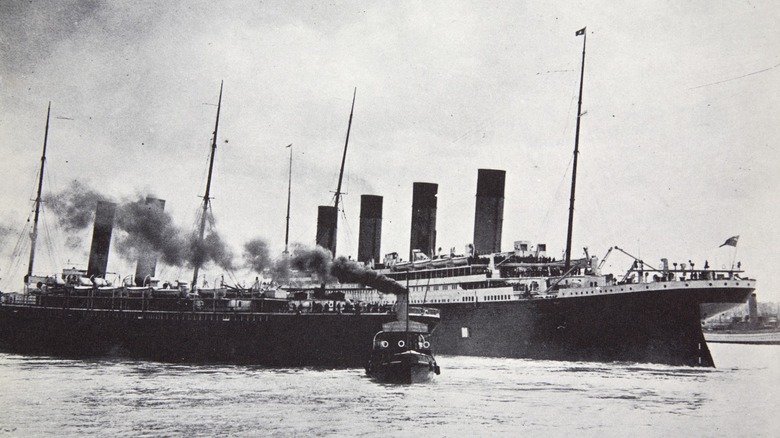

Since the RMS Titanic set sail and subsequently sank on its maiden voyage in 1912, it has been the subject of endless amounts of inquiry. It inspired one of the most successful Hollywood movies of all time and has spawned countless documentaries and books. The Titanic took over two years to build and finally set sail on April 10, 1912, only to sink a few days later on the 14–15th.

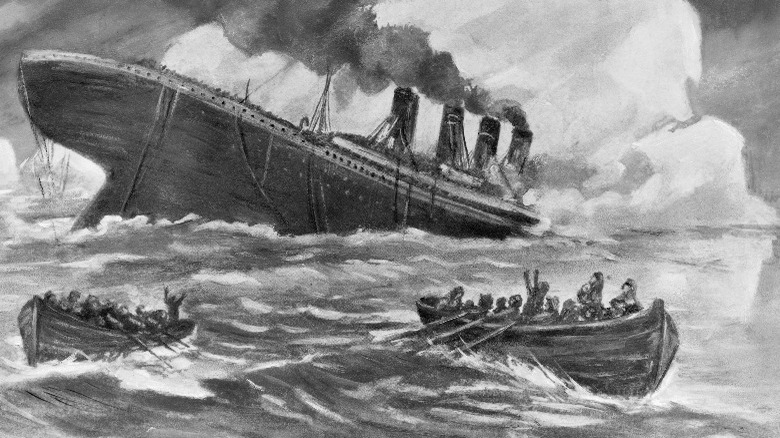

Before its departure, the Titanic was billed as the greatest ship of its day, but it's now considered one of the most epic failures of all time. It's estimated that over 1,500 passengers died in the wreck, and the ship was already more than halfway across the Atlantic Ocean on its journey from Europe to America when it sank. There were several safety flaws that contributed to the extraordinary death toll, including a wholly insufficient number of lifeboats.

Of the more than 2,200 passengers and crew, just over 700 made it out alive to be rescued. Due to the status and prestige of the Titanic, much of the passenger list consisted of the most affluent people of the day, including the ultra-wealthy John Jacob Astor. However, there were also many famous individuals who were supposed to be on the ship but for whatever reason backed out at the last minute.

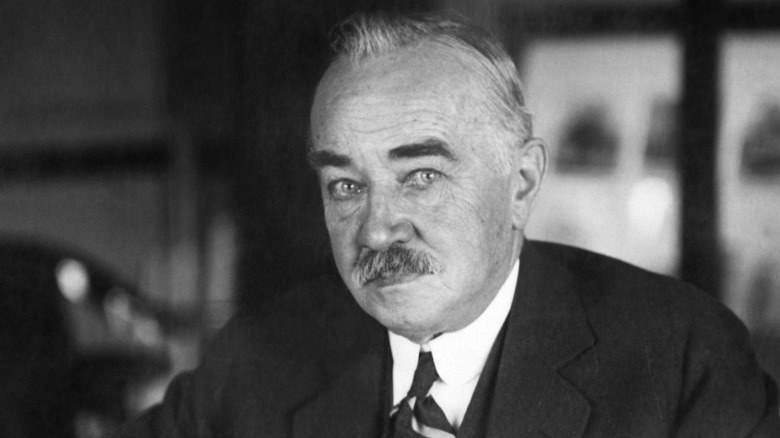

Milton Hershey

Milton Hershey founded the Hershey Chocolate Company, which is most well-known for its chocolate confections. Hershey was born in 1857 and founded the company in the late-1800s. He was inspired by seeing chocolate at the Chicago World's Fair in 1893, and in particular the Swiss style of milk chocolate. Soon, now-iconic treats like the Hershey Kiss were rolling off the line, and Milton Hershey became extremely wealthy.

Incredibly, he and the RMS Titanic almost came colliding together in 1912, just when his business was really booming. Due to their wealth, Milton and his wife Catherine Hershey were constant international travelers, and in April of 1912 they found themselves in Europe. During that time, Milton planned to return stateside for business and was going to set sail on the Titanic — but luckily for him, fate intervened.

He was planning on boarding the Titanic during its stopover in France and had already placed a deposit for his spot on the vessel when his plans abruptly changed. He was needed home sooner for an emergency business matter, and the Titanic would not get him there in time. Instead, he ended up leaving on April 6 aboard the SS Amerika. Cognizant of their incredible luck, Catherine later wrote to her mother-in-law that she felt God's hand at work for them always remaining safe in their travels (via Lancaster History).

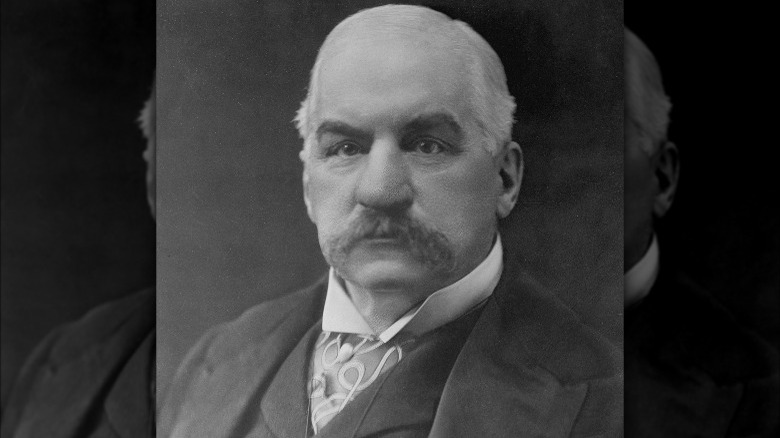

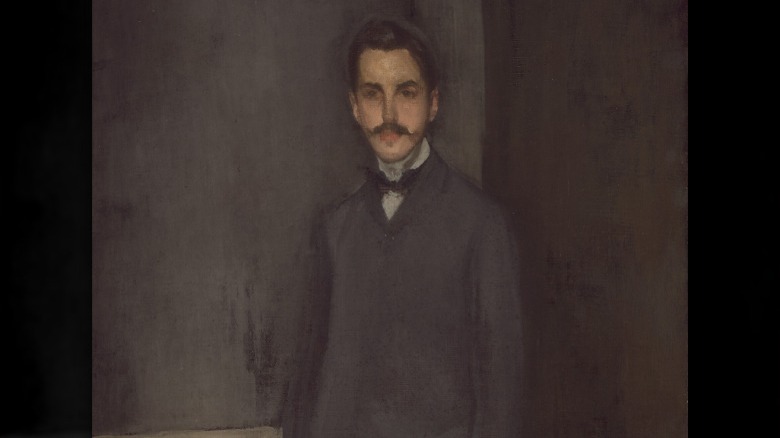

J.P. Morgan

Many people do not know, but besides his work in the steel and financial industries, John Pierpont (JP) Morgan actually played a significant role in the building of the RMS Titanic. Morgan was the owner of White Star shipping through his International Mercantile Marine Company, and White Star was the line that built the Titanic. Morgan had built his wealth in the 19th century by working in the banking and railroad industries and creating the General Electric company through a merger.

By the time the Titanic was set to sail in April 1912, Morgan was undoubtedly one of the richest and most powerful men in the world. It's little surprise, then, that Morgan would have been scheduled to take the magnificent Titanic's maiden voyage. In fact, he probably would have been on the ship as planned, if it had not been for the United States laws concerning importing art. Morgan had a huge collection of various art pieces throughout Europe but now wanted to get them home to take advantage of new lower import duties (via Bradford Matsen in "Titanic's Last Secrets").

He was all set to take the Titanic, but the month before it was scheduled to depart Morgan made the decision to stay in France and oversee the art arrangements himself. Morgan ended up dying less than a year after he was supposed to be on the Titanic on March 31, 1913, in Rome, Italy, at the age of 75.

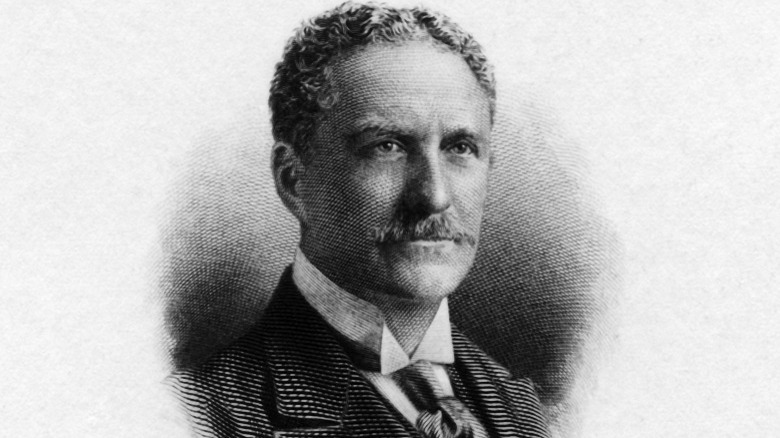

Guglielmo Marconi

Guglielmo Marconi was a man of many talents, and, as it turns out, many connections to the RMS Titanic. Born in 1874 in Bologna, Italy, Marconi's most valuable attachment to the Titanic was the wireless telegraph system that he created. The Marconi telegraph was the first wireless telegraph ever invented, and it would go on to have revolutionary implications for the future of long-distance communication. Marconi came up with the invention in the mid-1890s, and by the 1900s British battleships were already using it.

Marconi was able to demonstrate the telegraph's viability over increasingly bigger distances, and in recognition of his work, he won the Nobel Prize in 1909. Marconi and his wife, Beatrice Marconi, were invited on Titanic's maiden voyage when it departed in April 1912, but Guglielmo ended up on the Lusitania instead because he preferred its stenographer (per Degna Marconi in "My Father Marconi"). At the time, Beatrice was still planning to take the voyage, but their son became ill, thus canceling her trip. She and their daughter actually watched Titanic set sail from the docks at Southampton, England, on April 10.

Even though Guglielmo Marconi was not onboard the Titanic himself, his wireless telegraph machine was. Commercial ships realized the efficacy of his invention, and when the Titanic went down its officers desperately tried to relay for help by transmitting to other nearby ships. Marconi's telegraph undoubtedly helped save the lives of those who survived.

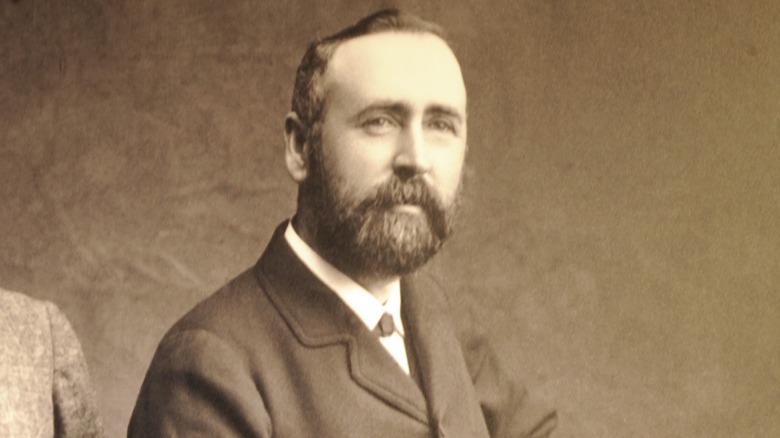

Henry Clay Frick

If it weren't for steel and coke magnet Henry Clay Frick's daughter, he may have been one of the 1,500 unlucky souls to have perished in the RMS Titanic disaster. Quentin R. Skrabec writes in "Henry Clay Frick: The Life of the Perfect Capitalist," that Frick, his wife Adelaide, and his daughter Helen, were all supposed to take the Titanic back home stateside from their European vacation. The Fricks had arrived in Europe with J. Horace Harding on vacation a few months earlier, and not only did they see the Vatican and Pompeii in Italy, they even made a stop in Egypt.

With the date of the Titanic's voyage approaching, young Helen started to feel ill. According to the New York Tribune, she became sick just prior to the Titanic leaving, and it forced both the Frick and the Harding families to postpone their return. Instead, the Fricks took another vessel back, which may have been the Mauretania with the Hardings.

Frick ended up giving his tickets away to J.P. Morgan, who also declined passage on the Titanic due to personal reasons. One of the wealthiest patrons to have almost boarded the Titanic, Frick made his money in the steel and coke mining industries, first with the Carnegie Brothers and then with the United States Steel Corporation.

J. Horace Harding

Traveling with Henry Clay Frick and his family on their 1912 European vacation was family friend J. Horace Harding (as Quentin R. Skrabec writes in "Henry Clay Frick: The Life of the Perfect Capitalist"). While Harding doesn't quite have the name recognition of Henry Clay Frick, he was still a very influential banker and financier in the early-20th century and a peer of J.P. Morgan. At one point, Henry Clay Frick, Morgan, and Harding all saw each on the vacation, possibly for a few nights in France or Italy.

Initially, when the Fricks declined to sail aboard the Titanic, they gave up their tickets to Morgan. However, when Morgan himself decided to stay in France for business reasons, he gave his tickets to Harding and his family. Harding also ended up declining to sail aboard the Titanic due to Helen Frick's illness, so he gave away his tickets, too (via the New York Tribune).

Harding lived for many years after the sailing of the Titanic, until his death from influenza in 1929. By that point, his friend Frick had already passed away, and Harding was serving as trustee of Frick's art collection.

Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt

Few families in history have the name recognition of the Vanderbilts, and it turns out that they have some surprising connections to the RMS Titanic. Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt was born in 1877 and would later become the head of the New York Central Railroad. He was the son of Cornelius Vanderbilt, one of the most successful and powerful businessmen in American history, and he inherited a huge empire upon his father's death. However, A.G.'s real passion was in horses, and he was a frequent attendee at horse shows and events.

In April 1912, A.G. Vanderbilt was supposed to board the Titanic just a few months after marrying his second wife, Margaret Emerson McKim, in London. In fact, his mother thought that he was on board the Titanic when she heard that it sank. However, a few days later A.G. was able to get her word that he was not on board, as per the Lewiston Morning Tribune, and he was likely still enjoying his time in London with his new wife.

It's unclear why A.G. declined passage, but it probably saved him and his new bride from a terrible fate. Tragically, he would perish three years later during another infamous sinking: the Lusitania. The Lusitania was a sad consequence of World War I, but reports emerged that A.G. acted heroically during the sinking, giving his life to save several children.

Theodore Dreiser

Usually, when your employer decides they want to spend less money on your accommodations it's a bad thing, but not in the case of Theodore Dreiser. Dreiser was a famous novelist most well known for his books "Sister Carrie," "The Financier," and "An American Tragedy," and he was almost a passenger on the Titanic. Though he never purchased tickets, he was infatuated by the massive vessel. Dreiser had left for Europe the previous November in 1911 to do research for a new book (via Jerome Loving in "The Last Titan: A Life of Theodore Dreiser"). He was accompanied by Grant Richards, an English publisher, who helped him get backing for his new work from the Century Company.

When Richards and Dreiser were set to sail back to America in April 1912, Richards had them take the Kroonland instead because it was cheaper. While Dreiser was probably a bit annoyed at the time, in hindsight he couldn't have been too upset at the change. While on board the Kroonland, Dreiser got word about the Titanic's sinking.

Dreiser wrote about his feelings hearing about the Titanic's sinking in his book "A Traveler at Forty." He wrote that he fell asleep "thinking about the pains and terrors of those doomed two thousand," and the news of the sinking put many of the passengers of the Kroonland briefly on edge.

George Washington Vanderbilt II

It turns out that Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt was not the only member of his illustrious family to cheat death by declining passage aboard the RMS Titanic. A.G.'s brother William Henry Vanderbilt had a son, George Washington Vanderbilt II, who was also supposed to be on the Titanic. George Washington was William Henry's eighth child, and he was born in 1862 in Staten Island, New York. He was an incredibly bright and talented individual and polyglot, who is largely responsible for the creation of the now famous Biltmore house and museum in Asheville, North Carolina, among the Blue Ridge Mountains.

In June 1898, he married Edith Stuyvesant Dresser, and that decision turned out to later save his life. Both G.W. and his wife were supposed to be on the Titanic, but it was his mother-in-law who ultimately persuaded them not. As recorded in the New York Tribune, the Vanderbilts were already having their luggage loaded onto the ship when the elder Dresser begged them to reconsider.

George Washington Vanderbilt, correctly realizing there are few things more dangerous than an upset mother-in-law, wisely decided along with his wife to abstain from taking the voyage. Unfortunately, their servant Frederick Wheeler, who had been sent on ahead, was not afforded the same opportunity, and he died when the ship went down.

John Mott

If John Mott had gone through with his initial plans to sail the RMS Titanic in 1912, the world might look a little differently today. Mott was a famous evangelist missionary who worked with both the Young Men's Christian Association (YMCA) and the World Missionary Conference during his life. According to Charles Howard Hopkins in "John Mott, 1865-1955: A Biography," Mott was "presumably" offered tickets and accommodations for the ship, but he refused for unknown reasons, though it was a close decision.

The decision turned out to be a smart one, as Mott could have easily perished in the disaster. When he found out about the Titanic's sinking upon his return, he saw his survival as a message that "The Good Lord must have more work" for him.

After narrowly avoiding the Titanic, Mott would continue to spread the word of religion throughout the world. He earned a Distinguished Service Medal for his work with the government in World War I, and he also later earned the Nobel Peace Prize for his work in the 1940s. Mott died in 1955 at the age of 89, more than 40 years after declining passage on the ship.

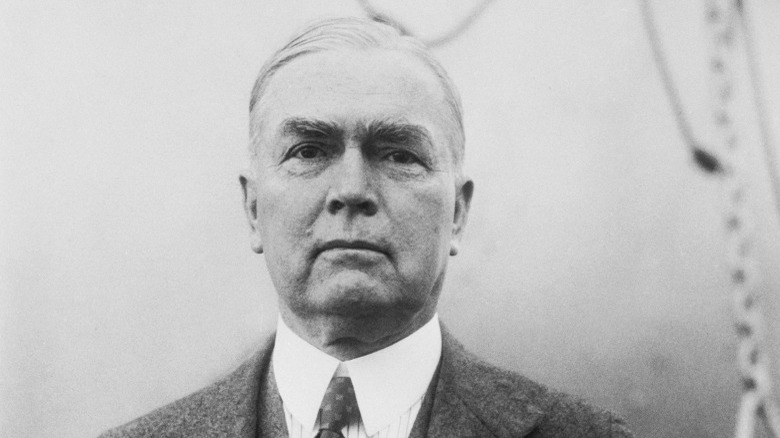

Robert Bacon

Among the statesmen to have almost boarded the RMS Titanic on its fateful voyage was Robert Bacon. Bacon had served as both the assistant secretary of state and the secretary of state under Theodore Roosevelt in the early 20th century. At the time of the voyage, Bacon was acting as the ambassador extraordinary and plenipotentiary to France and had been since 1909. He was supposed to take the Titanic back to America as part of being recalled, and his appointment as ambassador officially ended just a few days after it sank, on April 19, 1912.

The New York Times reported (thanks to Guglielmo Marconi's telegraph) that for whatever reason, Bacon and his wife ended up not sailing on the Titanic. They instead stayed back in France and were dining with the French President Armand Fallières at the Élysée Palace a few days later, celebrating their good luck. They eventually made their way home stateside on board La France, and Bacon was immediately replaced by Myron T. Herrick as the new ambassador. After avoiding the disaster of the Titanic, Bacon would go on to serve in the U.S. Army during World War I. He died in 1919 in his late 50s.

William Pirrie

Looking back now, it seems a bit peculiar, but two of the RMS Titanic's biggest backers were both absent from its dreadful maiden voyage. As Bradford Matsen explains in "Titanic's Last Secrets," both J.P. Morgan and William Pirrie were supposed to be aboard the Titanic when it left. However, they both canceled their plans just prior to it leaving. While Morgan stayed behind to help move his art collection, Pirrie was unable to sail due to serious health problems.

In the months leading up to the April departure date, Pirrie found himself getting sicker and sicker. He had multiple procedures done on his urinary tract to help ease his pain, but he was not able to recuperate in time for the Titanic. Pirrie was still at sea when the Titanic sank, but he was on his private yacht instead, healing from his latest surgery.

Pirrie was a viscount and baron and the owner of Harland and Wolff, which was an Irish shipbuilding firm. He was also a part of Morgan's International Mercantile Marine, through which his firm got the contract to build the Titanic. He was one of the architects behind the concept of luxury passenger liners and built the Olympic and Britannic "sister ships" of the Titanic. Pirrie's ultimate fate was still to perish at sea, which he did in 1924 aboard the Ebro.